Fajrul Islam/Getty Images

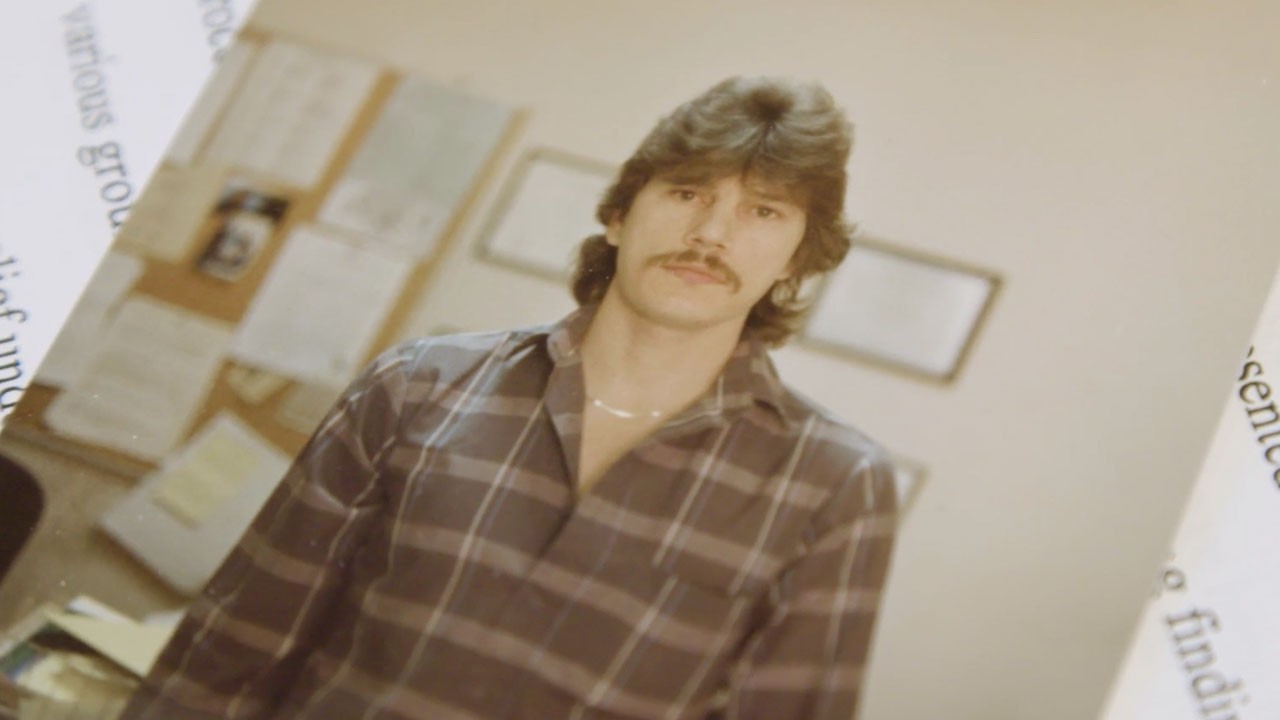

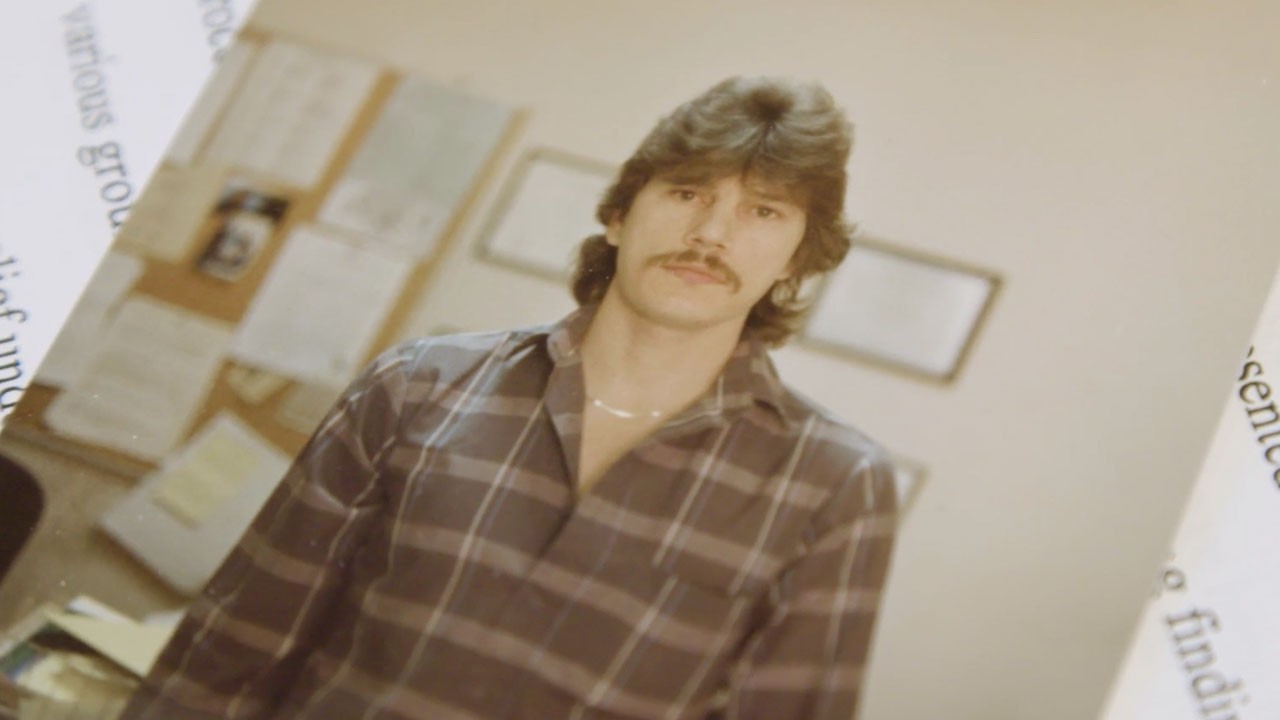

“I have an incurable blood cancer,” says David Mitchell, 66, a communications specialist in Maryland. “It’s incurable because it [evades] drugs.”In the last few months, CAR T cell therapy, a new FDA-approved treatment for stubborn cases of leukemia and lymphoma like Mitchell’s blood cancer, has been making its way to well-equipped cancer centers. The first gene therapy approved in the US, CAR T reconfigures a patient’s own immune system to detect and fight cancer. But the prices manufacturers are charging—up to $475,000 for one round of treatment—has created a whole lot of outrage.Mitchell, who has a cancer called multiple myeloma and is the founder of Patients for Affordable Drugs, has followed the development of CAR T and thinks gene therapy could be a game-changer for people in his position, but fears that the two companies offering CAR T, Novartis and Gilead, will keep it out of the hands of patients who need it. If these mid-six-figure prices become the standard for gene therapy, it could also put duress to the healthcare system as it tries to absorb the cost.“I’m very excited about CAR T,” he says. “I’ve already relapsed. I want CAR T, but I want it to be affordable. It’s not a last hope for anyone if you can’t afford it.”CAR T cell therapy, which has been under development for a decade, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration last year. The therapy adjusts the patient’s own T cells—white blood cells that act like bouncers on behalf the body’s immune system to detect and attack cancer cells.“T cells are designed to eliminate other cells,” says Stephan A. Grupp, director of the cancer immunotherapy program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who worked on clinical trials for CAR T. “But they don’t recognize that cancer is bad. They think it’s part of the body.” Through some genetic tampering, doctors can add synthetic chimeric antigen receptors—or CARs—to T cells. “This forces the T cell to see the cancer,” Grupp says.The treatment utilizes a genetic process discovered through HIV research, in which the disease modifies the DNA of T cells. For the procedure, clinicians draw blood from the patient, modify the T cells, and then inject them back into the body through a blood transfusion.The CAR T cells then self-replicate (an ability stolen from HIV), creating what one oncologist called “a living drug” within the patient’s body. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center started activating cells with chimeric antigen receptors in the early 2000s, Grupp says. In one clinical trial, 19 out of 27 patients with relapsed and refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) were in remission after six months (four with the help of at least one other other therapy). “This looks to be considerably more powerful than anything we have for these kinds of cancer,” Grupp says.Chemotherapy is the most common leukemia and lymphoma treatment at any stage. Steroids and stem cells have also been used.As is common for cancer treatments, there were significant side effects. All patients in the study experienced some degree of cytokine-release syndrome, an inflammatory response produced by elevated levels of inflammatory cells called cytokines, associated with T cell activation and proliferation. High temperatures, low blood pressure, and breathing and kidney issues are symptoms. About a third of the patients had to be re-hospitalized for cytokine-release syndrome and treated with antibiotics and pain medication.Still, the overall results were impressive to oncologists, particularly given CAR T’s potential importance to a population of leukemia and lymphoma patients whose cancer has returned after several other therapies. “I think it’s incredible,” says Alison Sehgal, a stem cell transplant oncologist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, which began offering the treatment last month. “The people who are using this have relapsed several times” on other therapies, Sehgal adds. CAR T cell therapy could be a lifeline particularly for younger blood cancer patients. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), one of the persisting types it’s approved to treat, is the most common malignancy of childhood and a leading cause of cancer death in children and young adults.The FDA has approved two forms of CAR T. Both are commercialized outgrowths of the research done at Penn Medicine and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and each is aimed at a different age group. In August, the Swiss multinational Novartis won approval to offer Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) for the treatment of patients 25 and younger who have relapsed twice, or whose B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has been dubbed refractory, meaning stubborn or resistant to treatment.In October, Kite Pharma, a newly purchased subsidy of California-based Gilead Sciences, was approved for Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) to treat adults with some kinds of large B-cell lymphoma whose cancer has not responded to treatment and who have relapsed after at least two other kinds of treatment.The prices are hefty: Novartis is charging $475,000 for the creation of CAR T cells for a single infusion (which was sufficient to begat a remission for most patients in clinical trials). A company spokesperson noted in an email that it is not charging if patients do not respond to the treatment within a month. The list price of Yescarta is $373,000.These are merely the prices to obtain specialized CAR T cells made from the patient’s blood. When you combine all the hospital costs with the price of treating cytokine-release syndrome, a round of Kymriah could cost an insurer $1 million, Mitchell says.Reached for comment, Nathan Kaiser, a spokesperson for Gilead, said, “We conducted extensive market research with commercial and government payers, as well as targeted cancer centers, to arrive at the list price of Yescarta."Sehgal, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, says that insurers have generally been receptive to paying for Kymriah and Yescarta because it has shown such positive results. A report in the journal Evidence-Based Oncology found that Medicaid officers in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, the two states closest to the institutions that pioneered the therapy, would pay for it.Nevertheless, the costs have raised concern. Clinicians for the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York have written in the Journal of the American Medical Association that Novartis “definitively shattered oncology drug pricing norms.” It’s difficult to compare the price for CAR T therapies to other treatments because gene therapy is new and a CAR T transfusion could be a one-time treatment. (The cost of most cancer therapies is measured by the amount, usually in the thousands, it costs to maintain treatment each month.)

More from VICE:

In an analysis for STAT News, Anna Kaltenboeck, a health economist, and Peter B. Bach, director of the Drug Pricing Lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering, said Novartis’ price “is both so large and so lacking in context that it is difficult to determine if it is too high by fivefold or too low by half.” Because this is the first gene therapy approved by the FDA, there are no precedents for healthcare economists to consider, and Novartis’ price could set the standard for this type of therapy.An analysis from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a Boston‑based independent nonprofit organization, is scheduled for March. Mitchell says his group, Patients for Affordable Drugs, has crunched some numbers with researchers from Harvard University, and that Novartis is making an obscene profit from CAR T.“It’s a brand new class of drugs,” Mitchell says. “It’s like they created a new class of fighter planes and were trying to charge the military. There would be no precedent and [the manufacturer] would set the price as high as they could, because it’s the best and the latest and they want to create a precedent that a jet like that should cost that much.” He adds that these prices will “make the [healthcare] system buckle and make families buckle.”When CAR T was in the research stages, Carl June, director of translational research at the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania which pioneered the therapy, said the cost of creating a treatment for an individual patient was $20,000. At a 2012 conference, June put the university’s “in-house cost” at “$15,000 to manufacture the T cells. (June was traveling and unavailable to comment when we reached out, according to a university spokesperson.)Patients for Affordable Drugs and their Harvard collaborators completed an analysis published on the website Health Affairs that “used a generous $40,000 production cost per infusion.” After accounting for royalty fees to Penn and to the makers of the viral vector used in production, shipping costs, as well as a refund to patients who don’t respond to treatment within a month—and thus not be charged as per Novartis’ guarantee—the group says Novartis would make an 84 percent profit margin on Kymriah over the next ten years.His group and their Harvard collaborators claim Novatis could charge $165,000 as a fair price that covers their costs, ensures a profit, and generates money to fuel R&D into other cancer drugs. “Why do they charge so much?” Mitchell asks. “Because they can.”Eric Althoff, head of global media relations for Novartis, said in an email that the company “carefully considered the appropriate price for Kymriah. We looked at many factors, including the medical and clinical value, the value to patients, the healthcare system and society, both in the near-term and long-term.”Althoff says that the company’s price is lower than figures provided by external health economists, as well as Novartis’ own experts, who determined a cost-effective price for Kymriah would be $600,000 to $750,000. “Recognizing our responsibility to bring this innovative treatment to patients, we set the price for Kymriah below that level at $475,000 for this one-time, single administration treatment,” he says. “We believe this will support sustainability of the healthcare system and patient access while allowing a return for Novartis on our investment.”He added, “The cost of Kymriah manufacturing has never been made public and cannot be for proprietary reasons. The oft-cited $20,000 to manufacture Kymriah is false.” Gilead Sciences did not respond to a call seeking comment about pricing for its CAR T treatment, Yescarta.Pharmaceutical companies often justify prices for new therapy that are exponentially more than the cost to manufacture the treatment on the cost to recoup research and development expenses, which can accumulate into the millions over years. But Mitchell says the National Institutes of Health has allotted $204 million in funding to the development of CAR T cell therapy at public institutions and universities. He lists the public funds gone to develop the drug in a Patients for Affordable Drugs analysis.“The taxpayers foot the bill for the basic science.” Mitchell says. “Then Novartis buys it, does one clinical trial, and sells it back to us at a huge profit.”Read This Next: Colleges Need to Do More to Support Students With Cancer

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

More from VICE:

In an analysis for STAT News, Anna Kaltenboeck, a health economist, and Peter B. Bach, director of the Drug Pricing Lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering, said Novartis’ price “is both so large and so lacking in context that it is difficult to determine if it is too high by fivefold or too low by half.” Because this is the first gene therapy approved by the FDA, there are no precedents for healthcare economists to consider, and Novartis’ price could set the standard for this type of therapy.

Advertisement

Advertisement