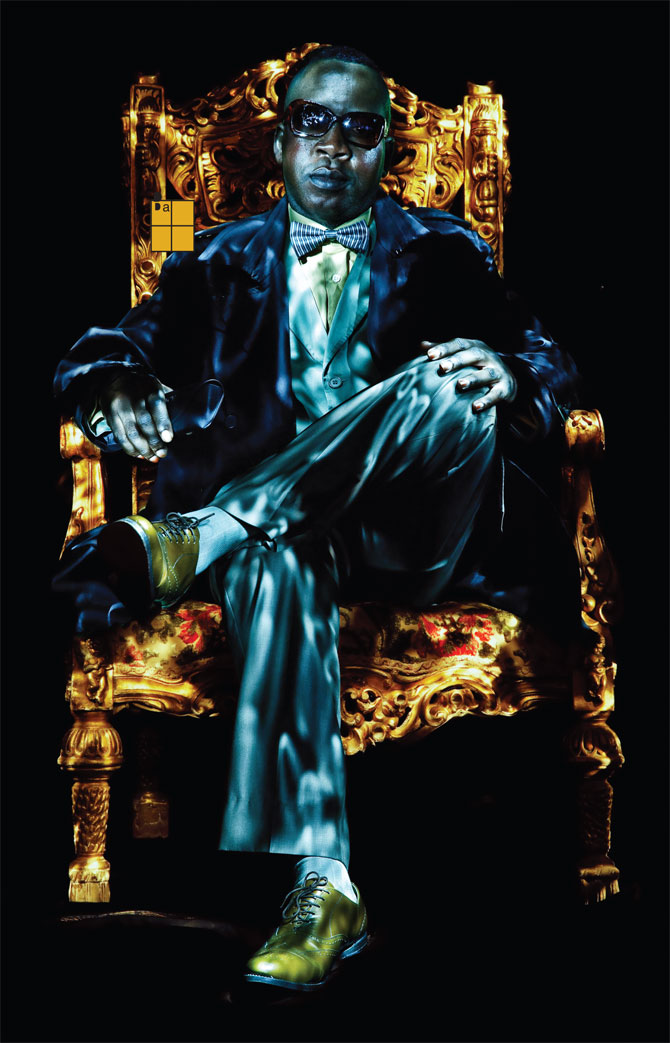

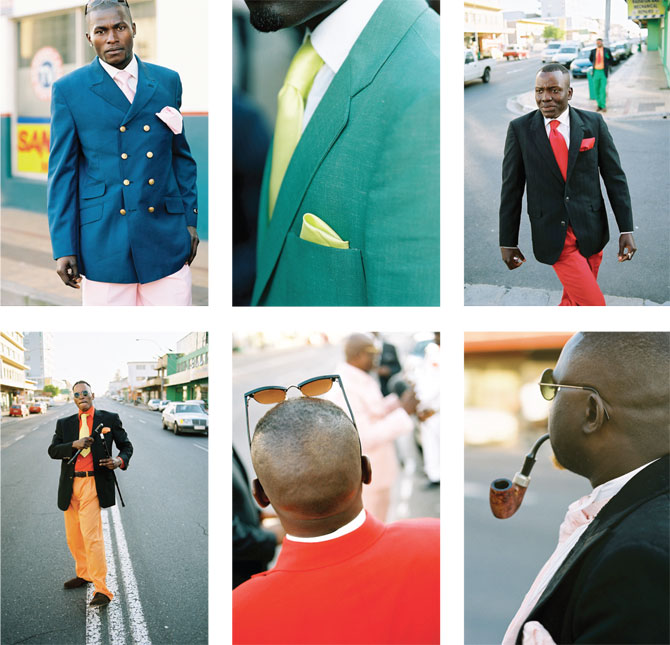

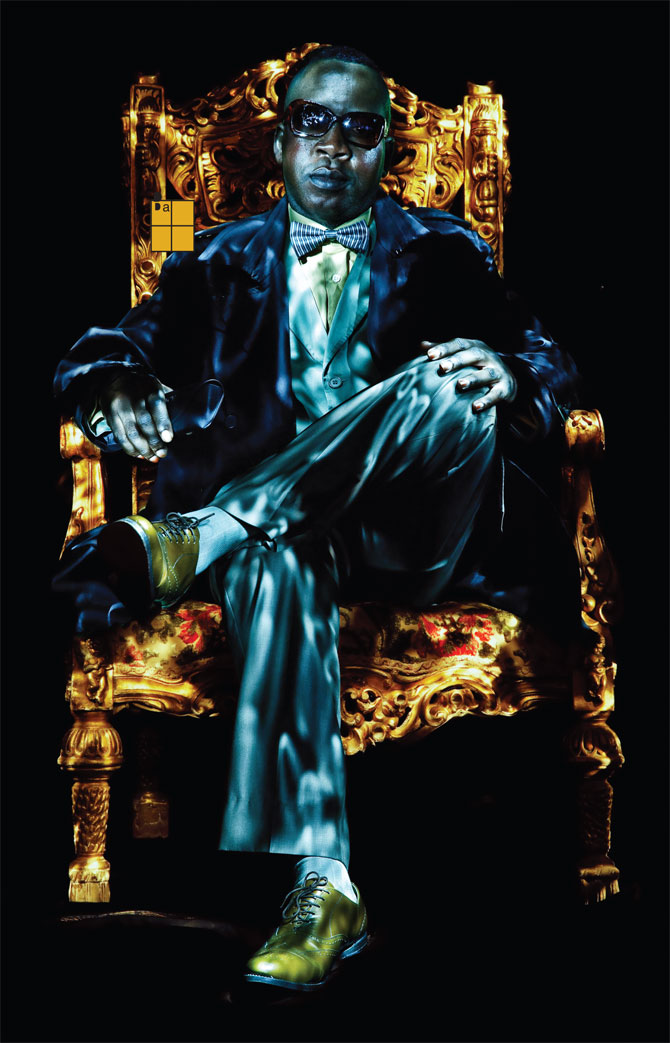

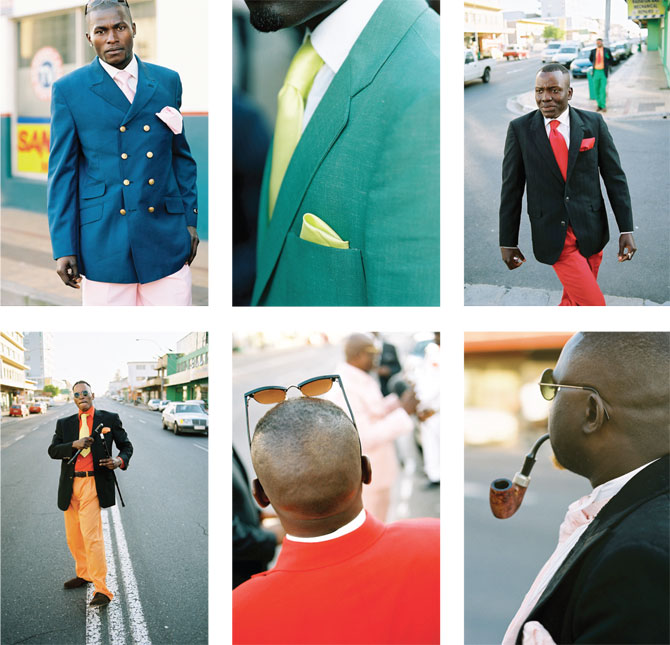

BY SEAN CHRISTIE, PHOTO BY WAYNE KEET The worldwide Congolese fashion cult known as La Sape (Society for the Advancement of People of Elegance) dates back to the return of African soldiers to Brazzaville after fighting for France in the First World War. After Zairean despot Mobutu Sese Seko tried to affect a return to traditional clothing in the 1960s, it instigated a La Sape revival bysoukousmusician Papa Wemba. The urban Congolese youth wanted nothing to do with Mobutu’s ‘Authenticity’, and so began the cult-like devotion to European fashion associated with the Sape movements of today.A lesser known aspect of this curious phenomenon is the ways in which La Sape have spread around the world since both the Democratic Republic of Congo and Congo Brazzaville collapsed into civil war in the mid to late nineties. The fact that La Sape thrives in South Africa, for example, in diaspora strongholds like Yeoville and Parow has gone virtually unregistered, despite the media’s slightly guilty interest in foreign Africans in the wake of last years xenophobic attacks.On Sunday August 16th, if you happened to be travelling down Voortrekker Road on the section between Parow and Bellville, you would have come across men in their thirties swaggering down the centre line wearing three piece suit ensembles inspired by the orange, green and yellow of the Congolese flag—a clue that Congo’s Independence Day had passed the day before. On all proximate street corners, and against the walls of electrical repair shops and cafés, men with bleached goatees flapped their suit vents to flaunt the labels of famous European designers. Pipes and cigars proliferated, as did disarticulated walking sticks. One man wore a skull and cross bones eye patch, another two ties, the second knotted to his belt so that it cleaved from the bottom of his Armani jacket in unmistakeable reference to a silk penis by Ralph Lauren.By sunset 200 men of elegance had massed outside the Congolese club La Reference, the largest gathering of La Sape in South Africa to date. The last Capetonian meet, which was also the first of its kind in the country, took place four years ago outside the original La Reference on Long Street. In explaining the lag time club owner John Phillida points to the expense of theSapeur’soutfits.“For these guys everything must be a famous brand, and they cannot be seen wearing the same things twice. Suits can cost R10000, shoes as much as R30 000 if they are Jimmy Weston handmade. And these guys are not rich, they are security guards, taxi drivers, some are even car guards, earning between R1 500 and R4 000 a month, so it takes a long time before they can appear in competition again.”The irony inherent in celebrating one’s independence from France in European suit ensembles (on a road named Voortrekker,nogal) was not lost on celebration organiser Gur-Lassavane Milandou, and neither was he blind to the perversity of a cult which drives some participants, struggling as they are under the restrictions of Refugee and Temporary Asylum Permits, to go without food just so they can afford their Tokio Kumagi’s. But the benefit apparently outweighs the contradictions.

The worldwide Congolese fashion cult known as La Sape (Society for the Advancement of People of Elegance) dates back to the return of African soldiers to Brazzaville after fighting for France in the First World War. After Zairean despot Mobutu Sese Seko tried to affect a return to traditional clothing in the 1960s, it instigated a La Sape revival bysoukousmusician Papa Wemba. The urban Congolese youth wanted nothing to do with Mobutu’s ‘Authenticity’, and so began the cult-like devotion to European fashion associated with the Sape movements of today.A lesser known aspect of this curious phenomenon is the ways in which La Sape have spread around the world since both the Democratic Republic of Congo and Congo Brazzaville collapsed into civil war in the mid to late nineties. The fact that La Sape thrives in South Africa, for example, in diaspora strongholds like Yeoville and Parow has gone virtually unregistered, despite the media’s slightly guilty interest in foreign Africans in the wake of last years xenophobic attacks.On Sunday August 16th, if you happened to be travelling down Voortrekker Road on the section between Parow and Bellville, you would have come across men in their thirties swaggering down the centre line wearing three piece suit ensembles inspired by the orange, green and yellow of the Congolese flag—a clue that Congo’s Independence Day had passed the day before. On all proximate street corners, and against the walls of electrical repair shops and cafés, men with bleached goatees flapped their suit vents to flaunt the labels of famous European designers. Pipes and cigars proliferated, as did disarticulated walking sticks. One man wore a skull and cross bones eye patch, another two ties, the second knotted to his belt so that it cleaved from the bottom of his Armani jacket in unmistakeable reference to a silk penis by Ralph Lauren.By sunset 200 men of elegance had massed outside the Congolese club La Reference, the largest gathering of La Sape in South Africa to date. The last Capetonian meet, which was also the first of its kind in the country, took place four years ago outside the original La Reference on Long Street. In explaining the lag time club owner John Phillida points to the expense of theSapeur’soutfits.“For these guys everything must be a famous brand, and they cannot be seen wearing the same things twice. Suits can cost R10000, shoes as much as R30 000 if they are Jimmy Weston handmade. And these guys are not rich, they are security guards, taxi drivers, some are even car guards, earning between R1 500 and R4 000 a month, so it takes a long time before they can appear in competition again.”The irony inherent in celebrating one’s independence from France in European suit ensembles (on a road named Voortrekker,nogal) was not lost on celebration organiser Gur-Lassavane Milandou, and neither was he blind to the perversity of a cult which drives some participants, struggling as they are under the restrictions of Refugee and Temporary Asylum Permits, to go without food just so they can afford their Tokio Kumagi’s. But the benefit apparently outweighs the contradictions. Photos by Dylan Culhane“Sapologiehas the power to bring the Congolese together, and we desperately need this unity because there are only three million of us in all the world, and here in South Africa no more than 8 000.”Sapologieis massive in Kinshasa DRC too but on Voortrekker Road, despite the exploding numbers of the DRC expatiate community, participants were overwhelminglyBrazzavil-leans.“After years of civil war between the north and south of my country,” explains Gur, “soccer, our great national pastime, was no more. In its absence the youth became obsessed with La Sape, which gave them a way of feeling clean and orderly in dirty, chaotic times.”Here in Cape Town many of the same conditions that sustainSapologiein Brazzaville are present for the expatriate Congolese—squalor, a dearth of entertainment, and the ever-present fear of persecution. The nation’s shameful xenophobic tendencies were demonstrated by the criers in passing taxis, one or two of whom shoutedamakwerekwerefrom their Quantum windows. One of the main explanations of xenophobia is embodied in the refrain: “They steal our women and jobs” and, in this light, gatherings of La Sape might be viewed as the ultimate incitement. Gur disagrees.“The problem with South African men is that they cannot imagine a universe in which they are not centrally located. La Sape has nothing to do with them, or their women. It’s a genuine Congolese passion, an enjoyment of clothes, nothing more.”La Sape gatherings are characterised by aggressive verbal displays, but these are entirely focused on personal fashion choices, accompanied by the flapping of suit vents to show labels, the lifting of trouser legs to exhibit shoes and socks, and in the case of a severe looking gentleman who went by the Sape name ofMa Paulo de Cape Town, a fuchsia tie was kept draped over a briar pipe for a full half an hour.It was surprising to hear Gervais (who becomes Libérateur on nights like these) boasting that he is from Saint-Denis “en face du Stade de France.” According to Gur, claiming a fashionable arrondissement of Paris as a home base is something of a local trait. “It is far better than saying that you come from Parow, Goodwood or Salt River, isn’t it?”

But it was to these deeply unfashionable suburbs that the Sapeurs returned after a meal of grilled tilapia and cassava, probably to press their security guard uniforms or check the oil in their taxis.

Photos by Dylan Culhane“Sapologiehas the power to bring the Congolese together, and we desperately need this unity because there are only three million of us in all the world, and here in South Africa no more than 8 000.”Sapologieis massive in Kinshasa DRC too but on Voortrekker Road, despite the exploding numbers of the DRC expatiate community, participants were overwhelminglyBrazzavil-leans.“After years of civil war between the north and south of my country,” explains Gur, “soccer, our great national pastime, was no more. In its absence the youth became obsessed with La Sape, which gave them a way of feeling clean and orderly in dirty, chaotic times.”Here in Cape Town many of the same conditions that sustainSapologiein Brazzaville are present for the expatriate Congolese—squalor, a dearth of entertainment, and the ever-present fear of persecution. The nation’s shameful xenophobic tendencies were demonstrated by the criers in passing taxis, one or two of whom shoutedamakwerekwerefrom their Quantum windows. One of the main explanations of xenophobia is embodied in the refrain: “They steal our women and jobs” and, in this light, gatherings of La Sape might be viewed as the ultimate incitement. Gur disagrees.“The problem with South African men is that they cannot imagine a universe in which they are not centrally located. La Sape has nothing to do with them, or their women. It’s a genuine Congolese passion, an enjoyment of clothes, nothing more.”La Sape gatherings are characterised by aggressive verbal displays, but these are entirely focused on personal fashion choices, accompanied by the flapping of suit vents to show labels, the lifting of trouser legs to exhibit shoes and socks, and in the case of a severe looking gentleman who went by the Sape name ofMa Paulo de Cape Town, a fuchsia tie was kept draped over a briar pipe for a full half an hour.It was surprising to hear Gervais (who becomes Libérateur on nights like these) boasting that he is from Saint-Denis “en face du Stade de France.” According to Gur, claiming a fashionable arrondissement of Paris as a home base is something of a local trait. “It is far better than saying that you come from Parow, Goodwood or Salt River, isn’t it?”

But it was to these deeply unfashionable suburbs that the Sapeurs returned after a meal of grilled tilapia and cassava, probably to press their security guard uniforms or check the oil in their taxis.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement