Joel Meyerowitz was part of a group of pioneering photographers that revolutionized the art world 50 years ago by taking color pictures at a time when everyone thought serious photos had to be in black and white. Over his decades-long career, he’s proved himself to be a master of street, landscape, and portrait photography. He is 74 years old. Olivia Bee is one of our favorite new photographers, and we featured her work in our most recent photo issue. She is 18 years old. We thought it would be fun to see how two nonsequential generations of photographers would interact, so we had Olivia interview Joel about photography, life, art, and his massive, two-volume retrospective book, Taking My Time, which was just released by Phaidon.Olivia Bee: I’ve been reading your book the last few days and it’s so beautiful. Like, it’s so amazing. I love it.

Joel Meyerowitz: That’s nice to hear. You’re the first person to have actually read the book and say something about it. Thank you for saying that. I don’t know how the book is going to read. I’m not a professional writer, but I felt I had to say something intimate and personal about the 50 years I’ve been working in this medium. I do think I found a certain tone, a voice that came out of me. And when I read it, I feel gratified, but who knows what anybody else thinks.I think it’s nice to hear all the stories behind everything and the transitions you went through with your work.

What do you do?I’m also a photographer.

Oh, that’s great. What’s your interest in particular?I shoot some editorial, some commercial, but I’d say I’m mostly interested in capturing moments that are important in my life.

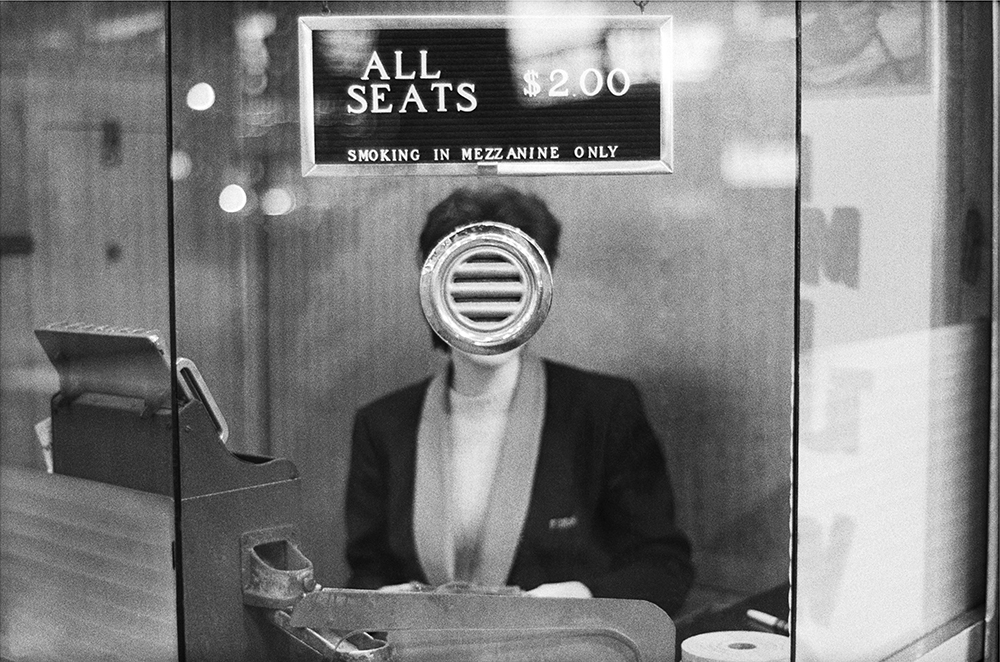

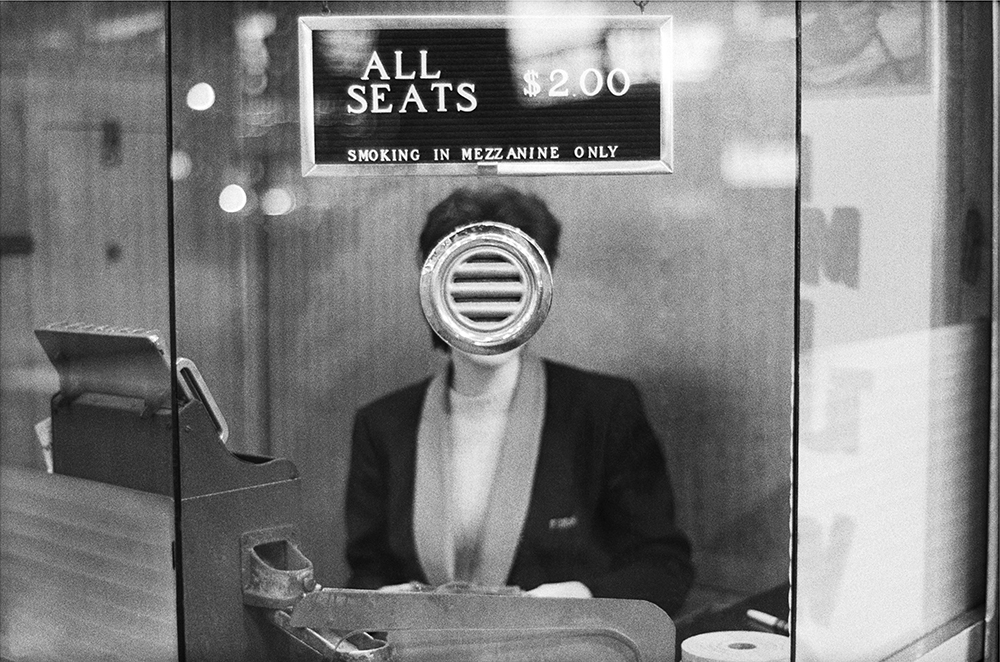

Isn’t that what it’s really all about? This tool is so perfect for intimate revelations about oneself and the world. Certainly there’s been a wonderful history of people like Nan Goldin who photograph their intimate experiences. You know, when Nan Goldin graduated college in Boston, I was the speaker at her graduation. Joel Meyerowitz, New York City, 1963 from Joel Meyerowitz: Taking My Time (Phaidon Press, $750.00 Limited Edition with signed print, November 2012) © Joel Meyerowitz, courtesy Phaidon.That’s so cool!

Joel Meyerowitz, New York City, 1963 from Joel Meyerowitz: Taking My Time (Phaidon Press, $750.00 Limited Edition with signed print, November 2012) © Joel Meyerowitz, courtesy Phaidon.That’s so cool!

She came up on stage in a white, kind of shabby, worn-out wedding dress. And I thought, Wow, this person’s really a character. She was only a student, she wasn’t Nan Goldin the artist yet. And afterwards, we were at a graduation party and she and I got to talking about her moving to New York, and within a month she moved there and she came to my class at Cooper Union. We hung out together and she showed me some of her early work. It wasn’t fully formed yet, but it had a kind of sweetness to it in the way she was connecting to her friends. I introduced her to Marvin Heiferman, who ran the Castelli Graphics Gallery, and he gave her a show.That’s a great story. How does it feel to have this overview of your work in a huge book?

Well, it’s not like it just happened overnight. I spent the last few years trying to put it together. When the book arrived a couple of weeks ago, I sat with it and read it cover to cover. It took me more than a whole day. When I was finished, it was as if I had read a book about someone else. And I found the person interesting in different ways at different times. I thought, Wow, I’ve met myself when I was a young man and saw myself go through various transitions in my life. My sense was that I said everything that I wanted to say in this book.That’s amazing. I’m so happy for you.

Well, thank you—I am too. I wasn’t trying to put out a book of my greatest hits. I felt it should be something that’s more personal and vulnerable and intimate, and that shows where things didn’t succeed, where there were dead ends along the way. I think as an artist you have to be willing to say, “I’m not perfect. I’m just struggling like everyone else.” The medium taught me along the way. I feel encouraged that I was able say, “This is who I am. Here it stands, naked in front of you, make what you can out of it.”I think that’s very brave. It’s cool.

It’s one of the reasons I did most of the writing in the book. I didn’t want to leave it to a curator to make assumptions about the work when I’m still alive. If I were dead I wouldn’t care. [laughs] I wanted to be able to say, “You know, this picture didn’t make any sense to me for a long time, but I couldn’t throw it away until finally I understood it.” It took me years to understand what the lesson was. Not what the picture was about, but what the lesson in the making of that picture was.How old are you now?I’m 18.

Wow, listen: You are in your first real consciousness of what it means to be an individual, a woman, an artist—and you’ll build on this. I was 24 when I started photography. So you got a six-year jump on me. Photo by Olivia BeeWhat do you think the future of photography will look like?

Photo by Olivia BeeWhat do you think the future of photography will look like?

In the larger sense, if you think of photography as a language, it’s now a language that billions of people around the world speak. It used to be much more secretive. You might have a camera you used for family outings and holidays, but there wasn’t the number of people who bought a camera to make art that we have today. There’s this vast international explosion of people communicating through images that show us a commonality across the world in the way we live our lives, the things that are meaningful to us. So I see it as a tool for disseminating a kind of humanistic expression that makes us all closer to each other. We feel each other’s pain in a more continuous way. So I see it as an incredible leap forward for human communication.With the way we build on digital technology now in such quick leaps and bounds, who knows what the next stage will be? It might not be chips that we put images on—it may be organic matter so that images are developed through biological processes of bacteria. I’m just speculating. In your lifetime you are going to see these things, but probably not in mine.You’ve seen a lot of change, I think.

Yeah I have; it’s been great.What do you think were the most pivotal points in your life that changed the way you shot?

The first film I put in the camera was color film because I didn’t know any better—the world was in color, it was natural. There was an argument at that time that color wasn’t art, that black and white was the art of photography. If you’re going against the conventional wisdom of any time, you immediately are in a conflict. I think it’s important for us to run into these conflicts along our artistic paths now and then because they give us something to stand up for. Of course, I didn’t know why or how to make the argument. But over time I learned what it was that I needed to say and how to think about things. It was enriching for me and it gave me courage. I think it takes a lot of negotiation with yourself to be an artist because if you depend on others for their ideas, you’ll be spun around in a million different ways. I’m sure this has happened to you. At your age you must be surrounded by the professional world of older artists like myself, whose works are filled with temptations. So how do you maintain your identity? I think it’s a challenging thing. What I think guided me through my work was always having to return to home base and say, “How do I feel? What does the work mean to me? Does it have meaning?” Because we’re always questioning the work, right? It’s a great process. What are you trying to say? It’s a lovely problem. Joel Meyerowitz, Roseville Cottages, Truro, MA, 1976 from Joel Meyerowitz: Taking My Time (Phaidon Press, $750.00 Limited Edition with signed print, November 2012) © Joel Meyerowitz, courtesy Phaidon.Do you have any advice for young photographers starting out, or people who are just interested in photography?

Joel Meyerowitz, Roseville Cottages, Truro, MA, 1976 from Joel Meyerowitz: Taking My Time (Phaidon Press, $750.00 Limited Edition with signed print, November 2012) © Joel Meyerowitz, courtesy Phaidon.Do you have any advice for young photographers starting out, or people who are just interested in photography?

I think that it would be the same thing I would say to someone who is older and more experienced if this question came up. It seems to me that there’s a moment when you press the shutter release on the camera when the person you are, the person holding the camera, says yes. Every time you take a picture, you’re saying yes to what you see. There should be a degree of consciousness about who you are in the world at that moment, a kind of integrated consciousness. It’s not blind luck, so if one can find what it is that makes you conscious, what gives you the pleasure of being alive at that moment, I feel that is what leads you to your own identity. Because in the long run, your individual identity will be revealed by the strength of the photographs you make in one year, ten years, 15 years—there’s a string. They’re like little jewels on the string and they carry all the messages that you were excited by when the world spoke to you. I think that’s what happens and I’m sure you’ve experienced this yourself. Somehow you have that gasp come over you—you think, Oh, oh, now! You raise the camera and maybe the thing has gone by now or maybe it’s just unfolding in front of you and you intercept it at the right moment. That right moment is your moment of being conscious. So I would say to young artists that are beginning, try to understand when you’re fully conscious and accept your identity being awakened by the world around you. If you listen to that, you’ll have a singular vision—it will be your vision.Thank you so much. It was so nice to talk to you and I feel very inspired and insightful now.

Thank you too! l like the way you present yourself. Your spirit feels very good to me.You can see more of Olivia's work here. And go check out Joel's new book here.

Advertisement

Joel Meyerowitz: That’s nice to hear. You’re the first person to have actually read the book and say something about it. Thank you for saying that. I don’t know how the book is going to read. I’m not a professional writer, but I felt I had to say something intimate and personal about the 50 years I’ve been working in this medium. I do think I found a certain tone, a voice that came out of me. And when I read it, I feel gratified, but who knows what anybody else thinks.I think it’s nice to hear all the stories behind everything and the transitions you went through with your work.

What do you do?I’m also a photographer.

Oh, that’s great. What’s your interest in particular?I shoot some editorial, some commercial, but I’d say I’m mostly interested in capturing moments that are important in my life.

Isn’t that what it’s really all about? This tool is so perfect for intimate revelations about oneself and the world. Certainly there’s been a wonderful history of people like Nan Goldin who photograph their intimate experiences. You know, when Nan Goldin graduated college in Boston, I was the speaker at her graduation.

Advertisement

She came up on stage in a white, kind of shabby, worn-out wedding dress. And I thought, Wow, this person’s really a character. She was only a student, she wasn’t Nan Goldin the artist yet. And afterwards, we were at a graduation party and she and I got to talking about her moving to New York, and within a month she moved there and she came to my class at Cooper Union. We hung out together and she showed me some of her early work. It wasn’t fully formed yet, but it had a kind of sweetness to it in the way she was connecting to her friends. I introduced her to Marvin Heiferman, who ran the Castelli Graphics Gallery, and he gave her a show.That’s a great story. How does it feel to have this overview of your work in a huge book?

Well, it’s not like it just happened overnight. I spent the last few years trying to put it together. When the book arrived a couple of weeks ago, I sat with it and read it cover to cover. It took me more than a whole day. When I was finished, it was as if I had read a book about someone else. And I found the person interesting in different ways at different times. I thought, Wow, I’ve met myself when I was a young man and saw myself go through various transitions in my life. My sense was that I said everything that I wanted to say in this book.That’s amazing. I’m so happy for you.

Well, thank you—I am too. I wasn’t trying to put out a book of my greatest hits. I felt it should be something that’s more personal and vulnerable and intimate, and that shows where things didn’t succeed, where there were dead ends along the way. I think as an artist you have to be willing to say, “I’m not perfect. I’m just struggling like everyone else.” The medium taught me along the way. I feel encouraged that I was able say, “This is who I am. Here it stands, naked in front of you, make what you can out of it.”

Advertisement

It’s one of the reasons I did most of the writing in the book. I didn’t want to leave it to a curator to make assumptions about the work when I’m still alive. If I were dead I wouldn’t care. [laughs] I wanted to be able to say, “You know, this picture didn’t make any sense to me for a long time, but I couldn’t throw it away until finally I understood it.” It took me years to understand what the lesson was. Not what the picture was about, but what the lesson in the making of that picture was.How old are you now?I’m 18.

Wow, listen: You are in your first real consciousness of what it means to be an individual, a woman, an artist—and you’ll build on this. I was 24 when I started photography. So you got a six-year jump on me.

In the larger sense, if you think of photography as a language, it’s now a language that billions of people around the world speak. It used to be much more secretive. You might have a camera you used for family outings and holidays, but there wasn’t the number of people who bought a camera to make art that we have today. There’s this vast international explosion of people communicating through images that show us a commonality across the world in the way we live our lives, the things that are meaningful to us. So I see it as a tool for disseminating a kind of humanistic expression that makes us all closer to each other. We feel each other’s pain in a more continuous way. So I see it as an incredible leap forward for human communication.

Advertisement

Yeah I have; it’s been great.What do you think were the most pivotal points in your life that changed the way you shot?

The first film I put in the camera was color film because I didn’t know any better—the world was in color, it was natural. There was an argument at that time that color wasn’t art, that black and white was the art of photography. If you’re going against the conventional wisdom of any time, you immediately are in a conflict. I think it’s important for us to run into these conflicts along our artistic paths now and then because they give us something to stand up for. Of course, I didn’t know why or how to make the argument. But over time I learned what it was that I needed to say and how to think about things. It was enriching for me and it gave me courage. I think it takes a lot of negotiation with yourself to be an artist because if you depend on others for their ideas, you’ll be spun around in a million different ways. I’m sure this has happened to you. At your age you must be surrounded by the professional world of older artists like myself, whose works are filled with temptations. So how do you maintain your identity? I think it’s a challenging thing. What I think guided me through my work was always having to return to home base and say, “How do I feel? What does the work mean to me? Does it have meaning?” Because we’re always questioning the work, right? It’s a great process. What are you trying to say? It’s a lovely problem.

Advertisement

I think that it would be the same thing I would say to someone who is older and more experienced if this question came up. It seems to me that there’s a moment when you press the shutter release on the camera when the person you are, the person holding the camera, says yes. Every time you take a picture, you’re saying yes to what you see. There should be a degree of consciousness about who you are in the world at that moment, a kind of integrated consciousness. It’s not blind luck, so if one can find what it is that makes you conscious, what gives you the pleasure of being alive at that moment, I feel that is what leads you to your own identity. Because in the long run, your individual identity will be revealed by the strength of the photographs you make in one year, ten years, 15 years—there’s a string. They’re like little jewels on the string and they carry all the messages that you were excited by when the world spoke to you. I think that’s what happens and I’m sure you’ve experienced this yourself. Somehow you have that gasp come over you—you think, Oh, oh, now! You raise the camera and maybe the thing has gone by now or maybe it’s just unfolding in front of you and you intercept it at the right moment. That right moment is your moment of being conscious. So I would say to young artists that are beginning, try to understand when you’re fully conscious and accept your identity being awakened by the world around you. If you listen to that, you’ll have a singular vision—it will be your vision.Thank you so much. It was so nice to talk to you and I feel very inspired and insightful now.

Thank you too! l like the way you present yourself. Your spirit feels very good to me.You can see more of Olivia's work here. And go check out Joel's new book here.