Adam Maier-Clayton lines up five pill bottles on the table at a restaurant in downtown Windsor, Ontario. He glances out the window toward the bar he used to work at a few years ago, before the pain from his mental illnesses made it nearly impossible for the 27-year-old to get out of bed.Every day he takes a combination of at least 15 of these prescription pills. Sometimes more if he needs to talk to people longer than an hour or do things like drive or grocery shop. He recently added a potent dose of medical cannabis oil to the regimen, but Maier-Clayton says it’s made no difference, like everything else he’s tried.“I took extra Ativan today because I expected the pain to interfere,” he said. “Usually I’m wrecked.”At first glance, it’s hard to tell anything is wrong. He’s sociable, talkative, and clearly lifts weights. But Maier-Clayton spends most days at home with his father, feeling as though his body has been burned with acid. Over the years, he’s been diagnosed with obsessive compulsive disorder, severe anxiety, and a dissociative disorder. Physical tics that began during childhood have grown into severe pain across his entire body. In the absence of a diagnosis for that physical pain, Maier-Clayton believes it is linked to his invisible mental illnesses. “It just feels like I’m a 27-year-old physically fit male with the body of an 85-year-old. I can’t function,” he said.That’s why he’s making plans to kill himself, likely by lethal drugs. He’s even been connecting with local drug dealers, hoping to source a powerful opioid that will put him out of his misery.“I don’t have an exact date in mind, but I can say that 2017 will likely be my last year,” he said.In the meantime, Maier-Clayton has become the face of mental illness in the ongoing right-to-die debate in Canada — and one of the youngest players in a discussion that focuses primarily on the elderly. He devotes any leftover energy to urging the government to amend the new doctor-assisted dying law to include him, and others with extreme mental illnesses.The law, also known as Bill C-14, only allows adult Canadians with select irremediable physical illnesses or disabilities whose death is “imminent” to end their lives with the help of a doctor or nurse practitioner.

“It just feels like I’m a 27-year-old physically fit male with the body of an 85-year-old. I can’t function,” he said.That’s why he’s making plans to kill himself, likely by lethal drugs. He’s even been connecting with local drug dealers, hoping to source a powerful opioid that will put him out of his misery.“I don’t have an exact date in mind, but I can say that 2017 will likely be my last year,” he said.In the meantime, Maier-Clayton has become the face of mental illness in the ongoing right-to-die debate in Canada — and one of the youngest players in a discussion that focuses primarily on the elderly. He devotes any leftover energy to urging the government to amend the new doctor-assisted dying law to include him, and others with extreme mental illnesses.The law, also known as Bill C-14, only allows adult Canadians with select irremediable physical illnesses or disabilities whose death is “imminent” to end their lives with the help of a doctor or nurse practitioner. Since the law came into effect in June, hundreds of Canadians have ended their lives with the help of a doctor, though countless more have been denied the service, including many suffering from mental illnesses.The federal health and justice ministers who oversaw the law’s creation have long opposed extending it to people with mental illnesses, arguing that they are a vulnerable group that needs to be protected, even though a Senate committee urged the government to do so.The authors of a study of cases in the Netherlands — the only country after Switzerland, and Belgium to allow euthanasia for those with severe psychiatric disorders including depression — urged other countries weighing similar laws to proceed with caution.Their research published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry found that in more than half of approved assisted deaths in the Netherlands involving those with mental disorders in recent years, people frequently cited loneliness as the reason for wanting to die, and also declined treatment that might have helped.

Since the law came into effect in June, hundreds of Canadians have ended their lives with the help of a doctor, though countless more have been denied the service, including many suffering from mental illnesses.The federal health and justice ministers who oversaw the law’s creation have long opposed extending it to people with mental illnesses, arguing that they are a vulnerable group that needs to be protected, even though a Senate committee urged the government to do so.The authors of a study of cases in the Netherlands — the only country after Switzerland, and Belgium to allow euthanasia for those with severe psychiatric disorders including depression — urged other countries weighing similar laws to proceed with caution.Their research published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry found that in more than half of approved assisted deaths in the Netherlands involving those with mental disorders in recent years, people frequently cited loneliness as the reason for wanting to die, and also declined treatment that might have helped. The Canadian government is looking into the matter further, as three independent reviews, announced earlier this month, will focus on requests for euthanasia from “mature minors,” advance requests from people suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and from those who wish to end their lives solely because of a mental illness. Those reviews aren’t expected to be completed until 2018.Maier-Clayton thinks it’s unlikely the law will change in the way he would like, and even if it did, he thinks it would be too late for him. That’s also why he has steered clear of the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association’s class action lawsuit that aims to repeal the law’s limited scope, as well as any other legal challenges.“It’s a good and bad thing,” he said. “I would feel trapped to stay throughout the proceedings, meaning years of horrifying pain.”**

The Canadian government is looking into the matter further, as three independent reviews, announced earlier this month, will focus on requests for euthanasia from “mature minors,” advance requests from people suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and from those who wish to end their lives solely because of a mental illness. Those reviews aren’t expected to be completed until 2018.Maier-Clayton thinks it’s unlikely the law will change in the way he would like, and even if it did, he thinks it would be too late for him. That’s also why he has steered clear of the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association’s class action lawsuit that aims to repeal the law’s limited scope, as well as any other legal challenges.“It’s a good and bad thing,” he said. “I would feel trapped to stay throughout the proceedings, meaning years of horrifying pain.”** Maier-Clayton walks up to the bungalow on a quiet snowy street about 15 minutes from downtown where he lives with his father and grandmother.A group of kids playing on the road outside joke about getting run over by one of the parked cars.He drove home with his friend Catrina, and she’s going to spend some time reading to him, something he hasn’t been able to do much of since May of last year. Like other cognitive actions like writing and speaking for too long, it’s become too painful. Maier-Clayton can last about another half an hour before the pain will take over.“You’ll have to excuse me,” he says opening the front door. “This house isn’t exactly my taste.”They turn toward his bedroom. A scented candle burns in the hallway, which is adorned with elaborate sconces, and colourful faux flowers.

Maier-Clayton walks up to the bungalow on a quiet snowy street about 15 minutes from downtown where he lives with his father and grandmother.A group of kids playing on the road outside joke about getting run over by one of the parked cars.He drove home with his friend Catrina, and she’s going to spend some time reading to him, something he hasn’t been able to do much of since May of last year. Like other cognitive actions like writing and speaking for too long, it’s become too painful. Maier-Clayton can last about another half an hour before the pain will take over.“You’ll have to excuse me,” he says opening the front door. “This house isn’t exactly my taste.”They turn toward his bedroom. A scented candle burns in the hallway, which is adorned with elaborate sconces, and colourful faux flowers. It’s a far cry from the busy life he was leading as an employee of a bank near Ottawa, where he used to live with his mother before their relationship went south. Always driven to succeed, Maier-Clayton graduated from the business program at Algonquin College and had dreams of working at a hedge fund.His father, Graham, says he never gave any thought to the right-to-die issue until his son starting bringing it up two years ago. “I was hoping that the medical profession could come up with something,” he said. “I’ve never encouraged him, but I understand it. I think he’s being stronger than me if I was in his position. I’m not going to give him a hard time.“And all doctors say my son is competent [to make his own decisions]. I know that too. So why can’t the general public know that?”Some days get so bad that the two have to communicate with made-up hand signals instead of talking.“He’s been able to do less and less over the last year,” Graham continued. “His condition has worsened and the pain comes on so much quicker and he’s told me he couldn’t get any worse than this, and then it does.”Maier-Clayton lies down on the double bed that takes up most of the room. There’s a generic nature print on the wall and large containers of protein powder on a shelf near the foot of the bed. A dresser with pills, Ferrari cologne, and an empty plastic milk container on top take up the rest of the room.

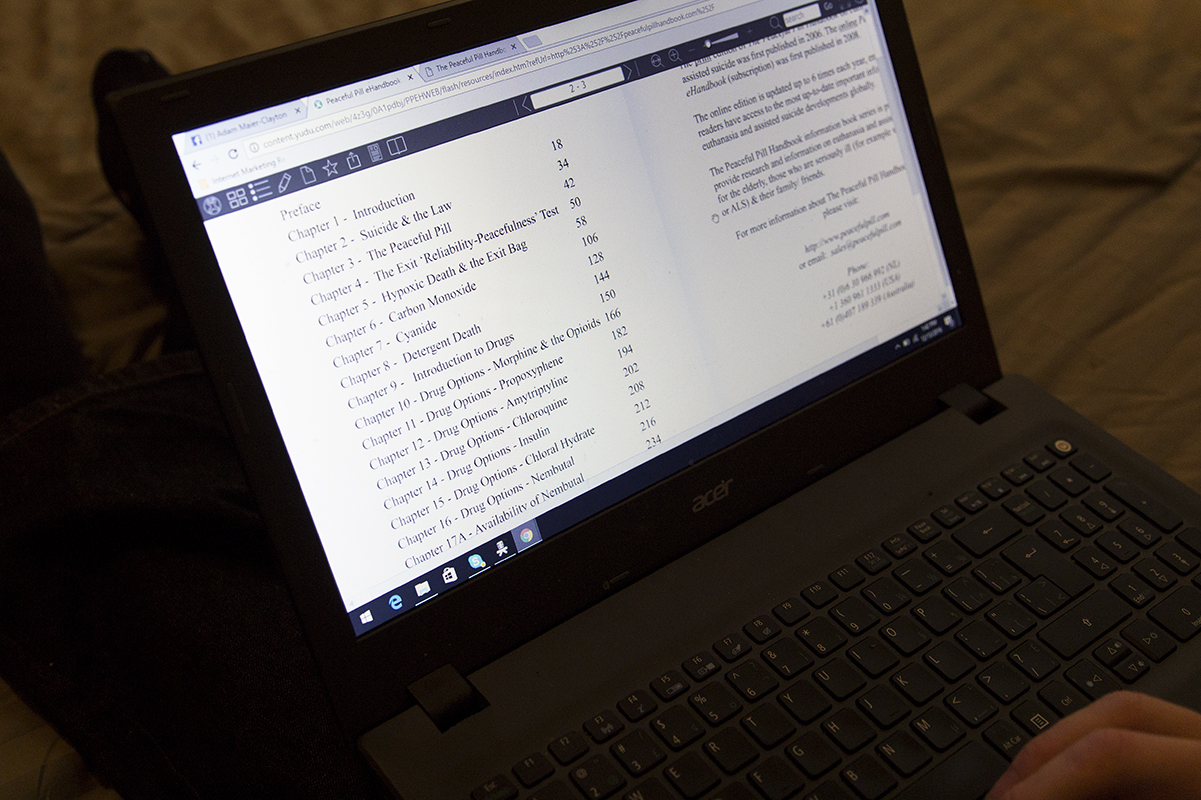

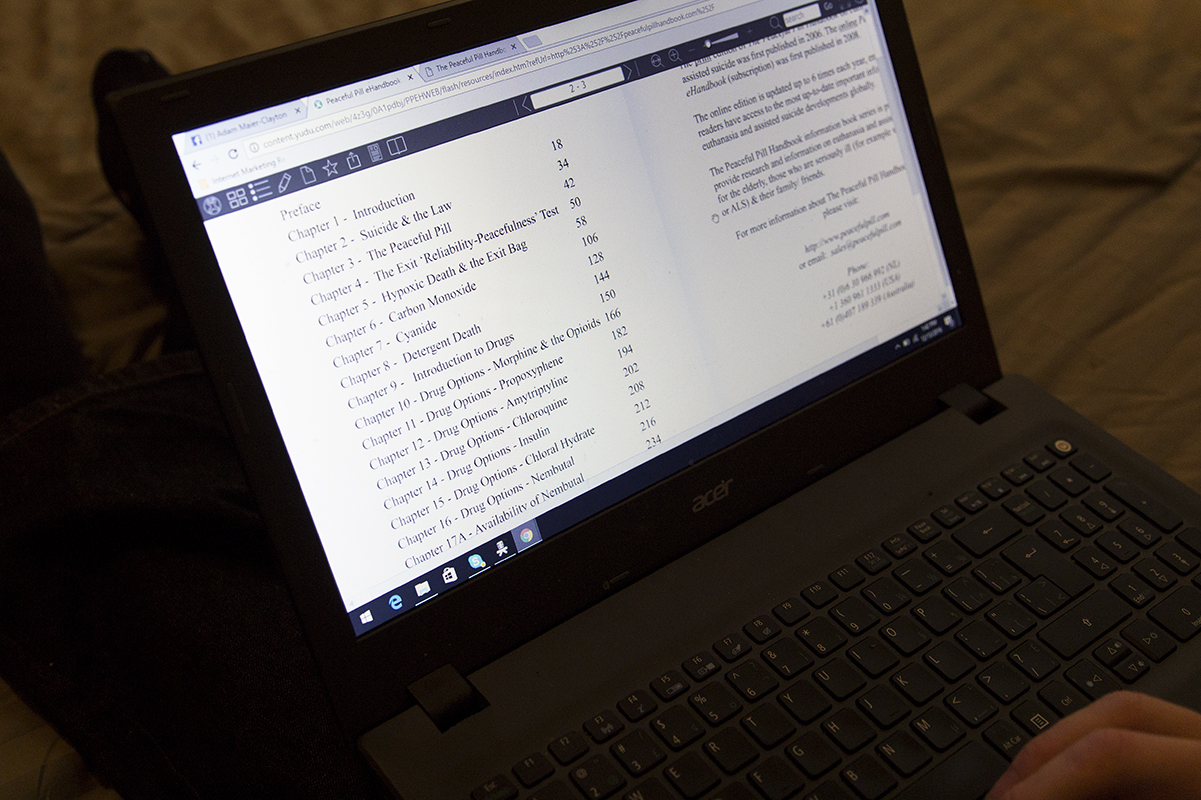

It’s a far cry from the busy life he was leading as an employee of a bank near Ottawa, where he used to live with his mother before their relationship went south. Always driven to succeed, Maier-Clayton graduated from the business program at Algonquin College and had dreams of working at a hedge fund.His father, Graham, says he never gave any thought to the right-to-die issue until his son starting bringing it up two years ago. “I was hoping that the medical profession could come up with something,” he said. “I’ve never encouraged him, but I understand it. I think he’s being stronger than me if I was in his position. I’m not going to give him a hard time.“And all doctors say my son is competent [to make his own decisions]. I know that too. So why can’t the general public know that?”Some days get so bad that the two have to communicate with made-up hand signals instead of talking.“He’s been able to do less and less over the last year,” Graham continued. “His condition has worsened and the pain comes on so much quicker and he’s told me he couldn’t get any worse than this, and then it does.”Maier-Clayton lies down on the double bed that takes up most of the room. There’s a generic nature print on the wall and large containers of protein powder on a shelf near the foot of the bed. A dresser with pills, Ferrari cologne, and an empty plastic milk container on top take up the rest of the room. “It’s basically just like a goddamn closet in here,” he says before opening his laptop. Catrina takes a seat opposite him.There’s a yellow Livestrong bracelet on his right wrist, but he insists it’s nothing to do with any sort of admiration for Lance Armstrong. It just represents his life motto. “Sometimes a person might encounter an unwinnable situation, but they should still remain as strong as they can be until it’s over,” he explains.He opens his online copy of the Peaceful Pill Handbook, originally published in 2006 by doctors as a manual on ways to end your life. Maier-Clayton says he recently bought it after joining Exit International, a non-profit pro-assisted suicide group started by Australian doctor Philip Nitschke. Most of the group’s membership is made up of people over the age of 75, making Maier-Clayton its youngest member.He clicks to the chapter that explains how different pharmaceuticals can hasten death. Catrina takes the laptop and looks at the screen.“This is like my version of a bedtime story these days,” he chuckles and leans back.Now, he’s considering powerful substances like carfentanil — a drug that’s meant to be used to tranquilize large wild animals but has since become responsible for dozens of overdose deaths across the country amid one of the worst drug safety crises Canada has ever seen.He already has a blue baggie of Stemetil tablets — a drug to prevent vomiting, and the first step in ensuring any illicit drugs he takes to die stay down.“It’s all so I have a peaceful, dignified insurance policy to die, because I know the government doesn’t care,” he said.Maier-Clayton’s story has provoked a strong reaction, with countless strangers extending offers of support, or accusing him of narcissism and seeking attention. His Facebook inbox is flooded with more than 1,000 unread messages.

“It’s basically just like a goddamn closet in here,” he says before opening his laptop. Catrina takes a seat opposite him.There’s a yellow Livestrong bracelet on his right wrist, but he insists it’s nothing to do with any sort of admiration for Lance Armstrong. It just represents his life motto. “Sometimes a person might encounter an unwinnable situation, but they should still remain as strong as they can be until it’s over,” he explains.He opens his online copy of the Peaceful Pill Handbook, originally published in 2006 by doctors as a manual on ways to end your life. Maier-Clayton says he recently bought it after joining Exit International, a non-profit pro-assisted suicide group started by Australian doctor Philip Nitschke. Most of the group’s membership is made up of people over the age of 75, making Maier-Clayton its youngest member.He clicks to the chapter that explains how different pharmaceuticals can hasten death. Catrina takes the laptop and looks at the screen.“This is like my version of a bedtime story these days,” he chuckles and leans back.Now, he’s considering powerful substances like carfentanil — a drug that’s meant to be used to tranquilize large wild animals but has since become responsible for dozens of overdose deaths across the country amid one of the worst drug safety crises Canada has ever seen.He already has a blue baggie of Stemetil tablets — a drug to prevent vomiting, and the first step in ensuring any illicit drugs he takes to die stay down.“It’s all so I have a peaceful, dignified insurance policy to die, because I know the government doesn’t care,” he said.Maier-Clayton’s story has provoked a strong reaction, with countless strangers extending offers of support, or accusing him of narcissism and seeking attention. His Facebook inbox is flooded with more than 1,000 unread messages. “There’s a lot of judgment from people telling me I need to try more treatment, or Jesus,” he grins. “I get where they’re coming from, but this is my life and it’s my choice.”One voice message on his Facebook is from a 24-year-old man in Iraq. He’s clearly distressed and tells Maier-Clayton he suffers from psychosis and can’t deal with reality. “I think of ending my life, but the problem is which way. I don’t have any help. I need advice,” the man pleads.Maier-Clayton says these types of messages are common, but there’s not much he can do except be there for them.“A lot of people with mental illness can actually speak up for themselves, but they don’t believe they can,” he said. “And there’s the stigma, so people choose not to. If some did speak up publicly, I wouldn’t feel like I have to stick around.”As a kind of last-ditch attempt to get to the bottom of why he’s in so much pain, Maier-Clayton says he’s waiting to hear back from a lab in the U.S. about whether or not he has Lyme disease, a bacterial infection spread by ticks that’s notoriously difficult to detect and treat in Canada.“I know it might not seem like it, but one thing I want to emphasize is that I don’t advocate death or suicide. I advocate treatment,” he said. “But after two years of no progress, I think that’s enough time.”He and his father are planning to go grave shopping in the next couple weeks.

“There’s a lot of judgment from people telling me I need to try more treatment, or Jesus,” he grins. “I get where they’re coming from, but this is my life and it’s my choice.”One voice message on his Facebook is from a 24-year-old man in Iraq. He’s clearly distressed and tells Maier-Clayton he suffers from psychosis and can’t deal with reality. “I think of ending my life, but the problem is which way. I don’t have any help. I need advice,” the man pleads.Maier-Clayton says these types of messages are common, but there’s not much he can do except be there for them.“A lot of people with mental illness can actually speak up for themselves, but they don’t believe they can,” he said. “And there’s the stigma, so people choose not to. If some did speak up publicly, I wouldn’t feel like I have to stick around.”As a kind of last-ditch attempt to get to the bottom of why he’s in so much pain, Maier-Clayton says he’s waiting to hear back from a lab in the U.S. about whether or not he has Lyme disease, a bacterial infection spread by ticks that’s notoriously difficult to detect and treat in Canada.“I know it might not seem like it, but one thing I want to emphasize is that I don’t advocate death or suicide. I advocate treatment,” he said. “But after two years of no progress, I think that’s enough time.”He and his father are planning to go grave shopping in the next couple weeks.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

After taking a minute to pronounce the word “barbiturate” properly, Catrina begins reading. “An overdose of a barbiturate can depress brain function so severely that respiration ceases and the person dies.“Barbiturates are also well absorbed rectally, and some countries have marketed forms of suppositories,” she recites.“That would not be my drug of choice!” Maier-Clayton interjects and smiles. “I’m trying to go with a little dignity.”**The law, however, has forced him to make risky choices. He’s been networking with drug dealers, looking at importing illegal substances, regardless of the consequences.“I’ve always avoided criminal activity and malicious behavior. I tried to teach myself to be a good person,” he said. “The worst thing I’ve done is smoke pot three times.”“I’m trying to go with a little dignity.”

Advertisement