A Medicaid expansion patient in California. Photo by Wally Skalij/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

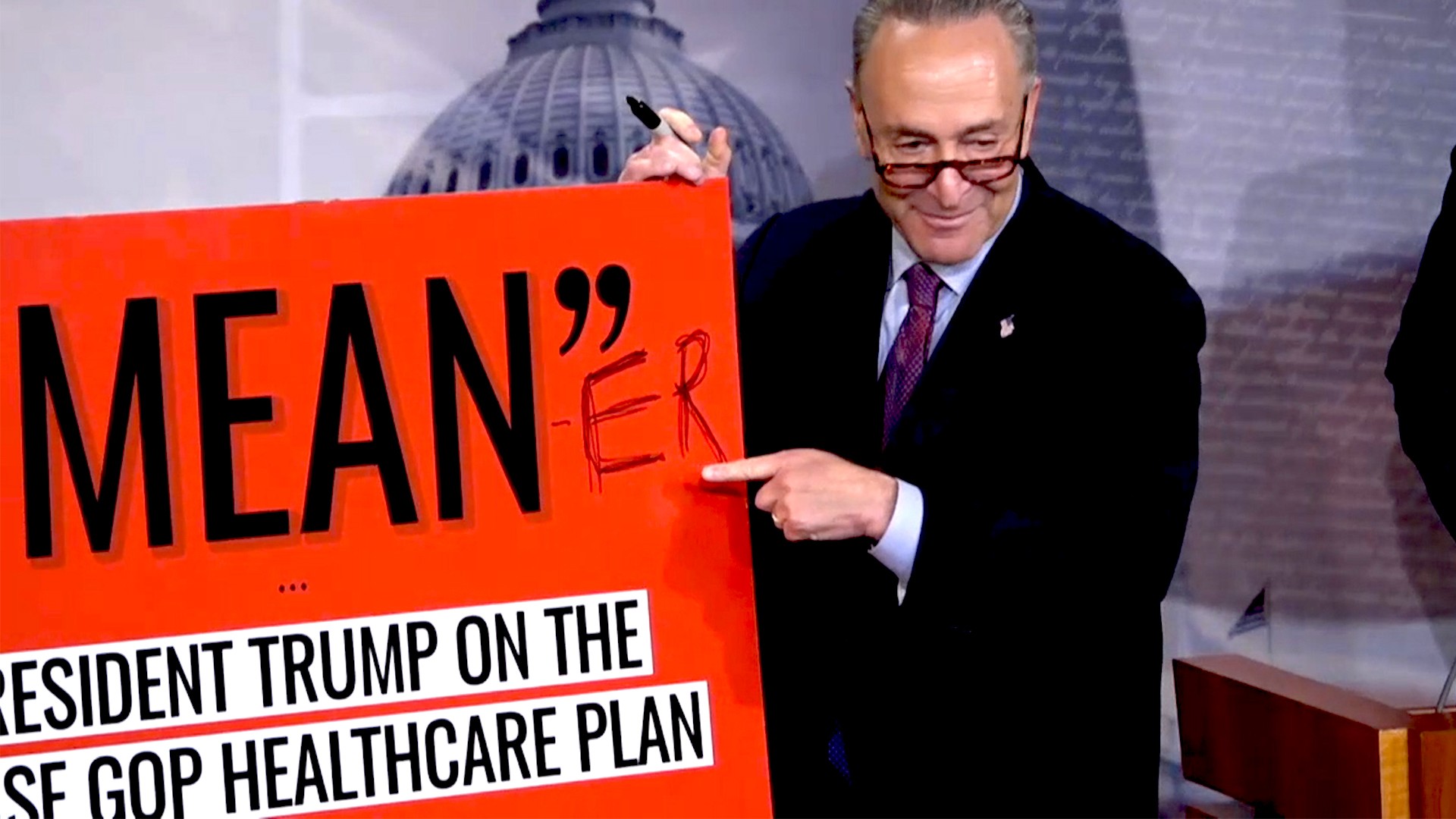

In January 2016, the head of the Wyoming Medical Center in Casper issued a dark warning. The hospital was facing growing budget shortfalls, in good measure because it was serving more poor and uninsured patients who couldn't pay. The state legislature had declined to help fix the problem, rejecting federal money to expand Medicaid as allowed under Barack Obama's Affordable Care Act. Now it was considering a bill to reverse that position.If Wyoming continued to spurn the money, said hospital CEO Vickie Diamond, layoffs might be coming. "I have 25 to 30 people in finance. So if my billing could be done elsewhere… That's jobs, that's people. That's not what I want, but you get back office efficiencies," she said.The Wyoming legislature paid no mind, killing the bill the following month. In June, Diamond called a somber press conference to announce that the hospital's budget problems had forced her to let go 58 workers and leave another 57 jobs vacant.The hospital wasn't the first to lay off staff because its state rejected ACA money. The Mercy health system runs hospitals in Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma. In 2014, it announced it was firing about 300 workers. Prominent among the reasons, according to a Mercy spokesperson, was the rejection of Medicaid expansion by three of the four states where it operates.If a Republican healthcare bill repeal gets rid of the Medicaid expansion, as Senate and House leaders want, it may do more than knock off millions of people from the insurance rolls—it could also slow state economies, even in non-expansion states.Democrats have argued that the GOP's Medicaid cuts are "cruel," a line of attack that seems to be working given the widespread unpopularity of the Republican reform scheme. But whatever the morality of the legislation, a likely outcome seems to be lost jobs and suddenly struggling economies.

Watch: The Senate healthcare bill has a numbers problem

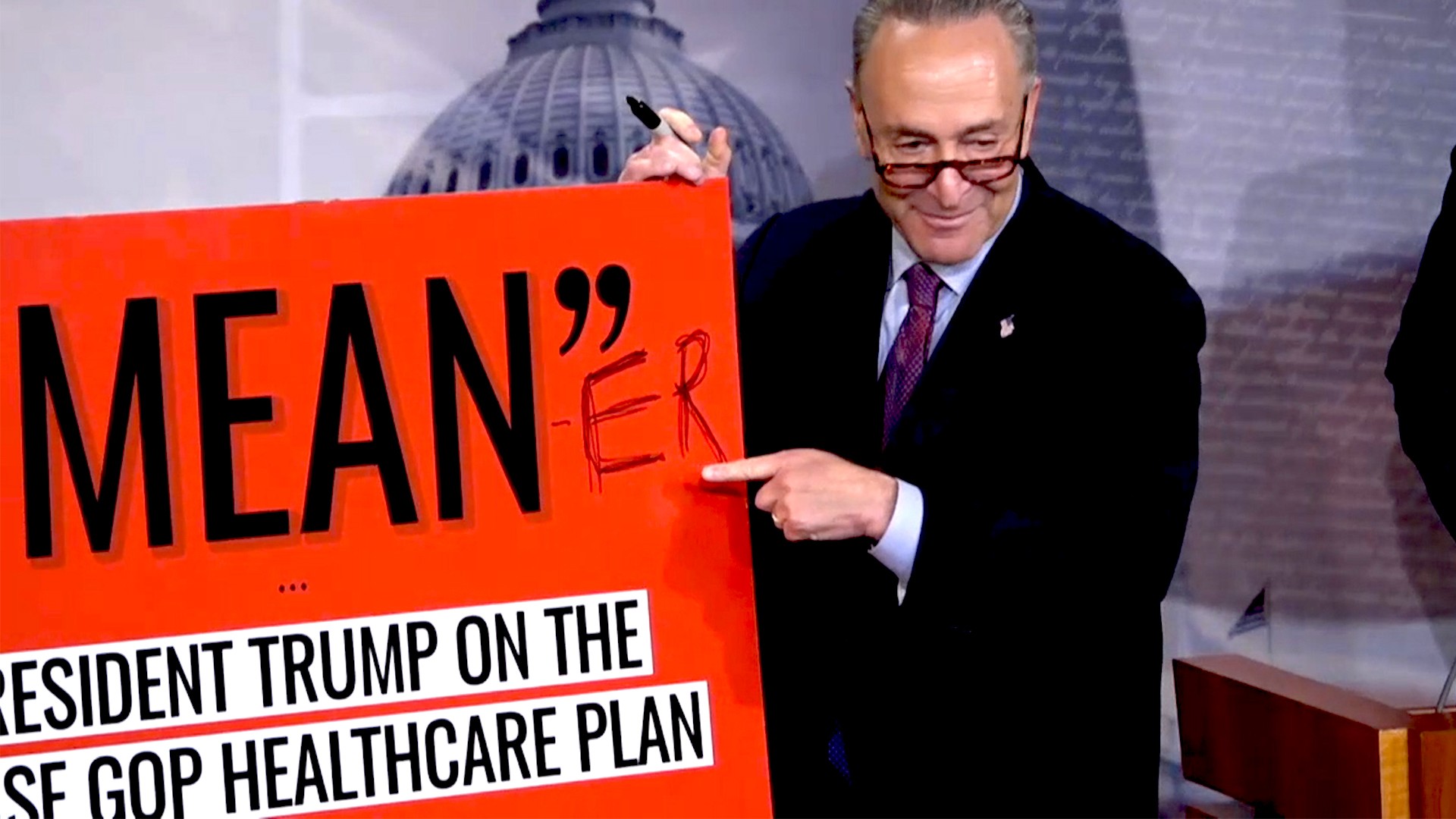

Those repeal plans are on hold now after top Republicans realized they didn't have the votes in the Senate to pass their bill. A bill has already passed the House; both versions would roll back the expansion, which allowed states to expand their Medicaid coverage to adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty line. Whatever tweaks are made to the Senate bill, the expansion will likely still be on the chopping block. The only real argument among Republicans about the expansion appears to be how long to let it survive.Republican leaders in the 19 states that rejected the Medicaid money argued in part that their states would need to raise taxes or cut other parts of their state budgets to cover the small matching share they'd need to pay under the expansion—5 percent of the expansion costs in 2017 and 10 percent from 2020 forward. (That's far less than what states contribute to provide regular Medicaid recipients with coverage.) Those tax increases and budget cuts, they said, would hurt economic growth.But in states that have accepted the money, the reverse is happening.Take Michigan. A skeptical state legislature passed a bill in 2013 accepting the new Medicaid money but required cuts in other parts of the budget or more tax revenue to cover the state's share of the costs. Otherwise the expansion program would end.As it turns out, the legislature's own fiscal analysts project that the expansion will actually boost the budget. It will save $182 million in state spending on mental health programs, prisoner health costs, and other health costs in the 2017–2018 fiscal year. By 2020, when the state's matching share rises to 10 percent, the expansion will still save a projected $13 million because of the cut in state government outlays for those and other programs.Overall, the Michigan expansion will increase personal income in the state by $2.3 to $2.4 billion a year from 2017 to 2021 and will generate between 30,000 and 38,000 jobs a year, University of Michigan researchers reported in a February New England Journal of Medicine article.Or consider Colorado, where the legislature passed Medicaid expansion in 2013. An analysis by Colorado State University researchers found that expansion will grow the state's GDP by an extra $4 billion and 30,000 jobs a year from 2017 through 2021. Recent studies by independent analysts in New Mexico, Alaska, Arkansas, and Kentucky have come to similar conclusions.And what if the expansion is repealed? An analysis in January by researchers at the Commonwealth Fund and George Washington University looked at the likely results. Repeal would cause the 31 expansion states and DC to lose a total of 1.2 million jobs and suffer $200 billion in lost business output by 2019, they concluded. It would even hurt the non-expansion states because goods and services get bought across state lines—non-expansion Utah would lose almost 9,000 jobs in 2019 under repeal.Phyllis Resnick, an economist who was a co-author of the Colorado study, points to a domino effect contributing to those consistent findings. Healthcare dollars create more local economic growth than do dollars spent on consumer goods like TVs and computers, which aren't usually made locally."When I go and seek medical care, that spending goes to a local practitioner," she explains. "That practitioner then has a little more income and can take their family out to dinner. Then the server has a little more money, and they spend more, and so forth."The opposite happens when patients lose coverage. Fewer patients with insurance coverage means less money to pay healthcare professionals, and the resulting downward economic impacts are more likely to be felt locally.NYC Health + Hospitals, which runs the country's largest public health care system, projects that eliminating the Medicaid expansion would raise the number of uninsured patients they serve from about 425,000 to more than 600,000. Hospitals in the system would be delivering more care that they wouldn't get paid for. John Jurenko, an NYC Health + Hospitals vice president, won't speculate about whether that would mean layoffs, which would have ripple effects on the city's economy—he's optimistic that the repeal efforts can be defeated.If the Republican bill does fail, the shadow of fewer jobs and slower growth looming over the repeal bill will surely be a factor, especially for Republican senators from expansion states. Those include Dean Heller of Nevada, who last week signaled his provisional opposition, Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia, who's undecided, and Alaska's two senators, who also haven't said which way they'll vote.Don't count medical professionals in the coalition of the undecided. At least 15 medical associations, like the American Hospital Association, American Medical Association, and America's Essential Hospitals, have come out against the Senate bill."Could Stephen King write a scarier version of this and put it on the Senate floor?" asks Jurenko. "I don't think so."Steven Yoder writes about criminal justice and domestic policy issues. His work has appeared in Salon, Al Jazeera America, the American Prospect, and elsewhere. Follow him onTwitter.

Advertisement

A wave of new studies point to the positive economic effects on state economies of offering Medicaid to the near-poor under Obama's signature law. If more people have insurance, it means they are more likely get the care they need, which in turn pays the salaries of health workers, who spend their earnings on restaurants, groceries, and movies. That's according to an analysis last spring by health economist Michael Chernew of the Harvard Medical School. And the newly enrolled use money they don't have to spend out-of-pocket on healthcare to pay for more housing, food, and other goods.Related: A Year-by-Year Breakdown of the Damage Done by Trumpcare

Advertisement

Watch: The Senate healthcare bill has a numbers problem

Those repeal plans are on hold now after top Republicans realized they didn't have the votes in the Senate to pass their bill. A bill has already passed the House; both versions would roll back the expansion, which allowed states to expand their Medicaid coverage to adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty line. Whatever tweaks are made to the Senate bill, the expansion will likely still be on the chopping block. The only real argument among Republicans about the expansion appears to be how long to let it survive.Republican leaders in the 19 states that rejected the Medicaid money argued in part that their states would need to raise taxes or cut other parts of their state budgets to cover the small matching share they'd need to pay under the expansion—5 percent of the expansion costs in 2017 and 10 percent from 2020 forward. (That's far less than what states contribute to provide regular Medicaid recipients with coverage.) Those tax increases and budget cuts, they said, would hurt economic growth.

Advertisement

Advertisement