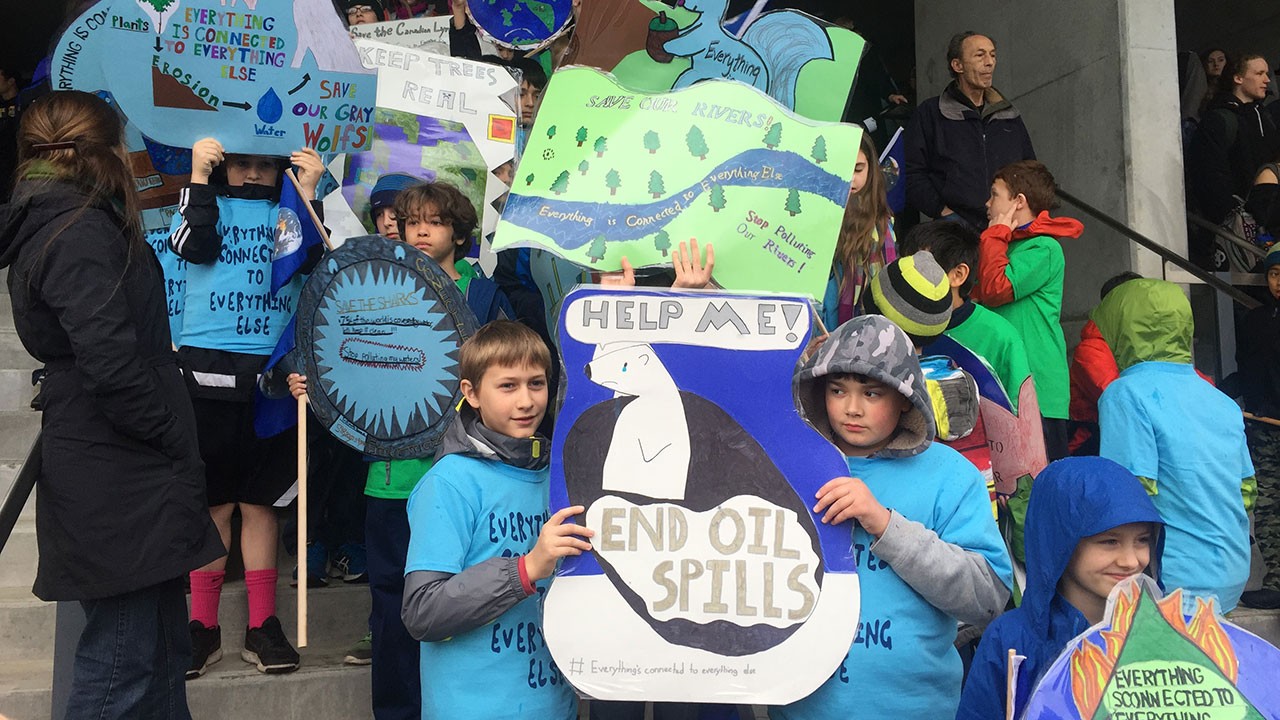

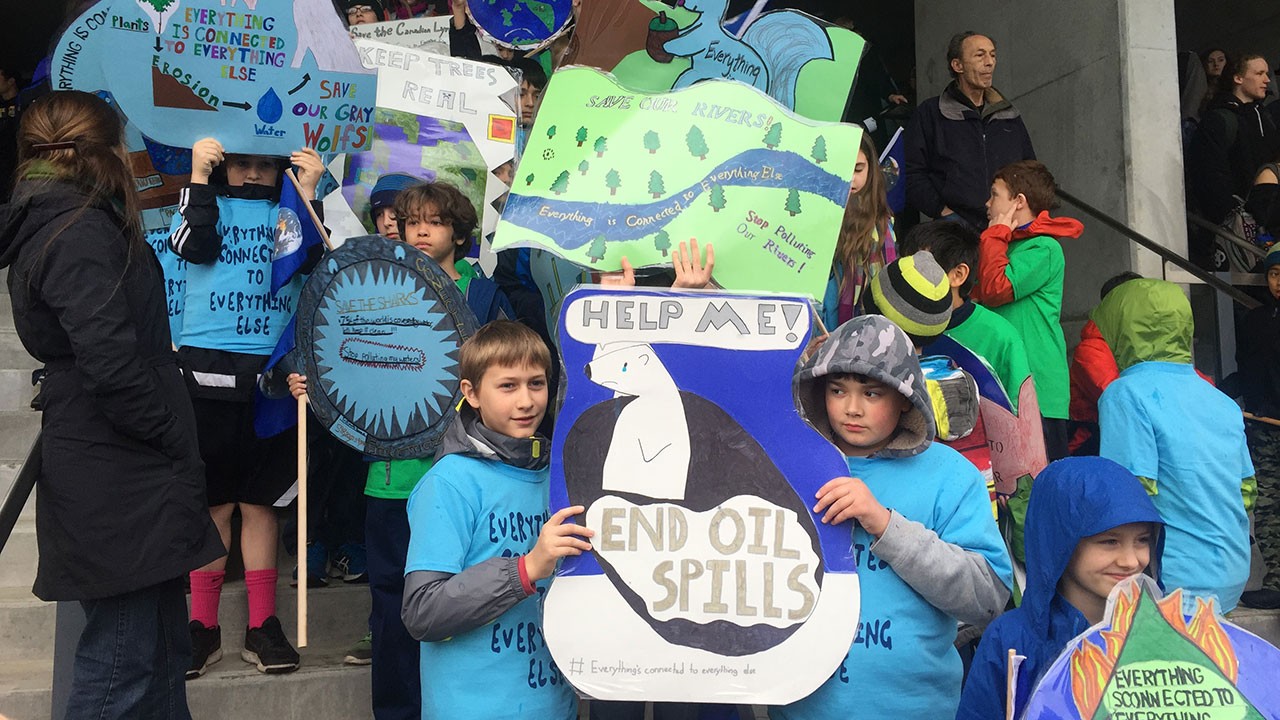

Photo by Ronen Tivony/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

On Wednesday, one of the largest university systems on the planet could choose to divest from the top players in the fossil fuel industry once and for all.Seventy-seven percent of voting faculty-members at the University of California, which has ten campuses throughout the state, agreed earlier this month "to divest the university's endowment portfolio of all investments in the 200 publicly-traded fossil fuel companies with the largest carbon reserves," according to a statement from the school's Academic Council. It's now up to the University Regents to decide whether to make the overwhelming vote official as part of a memorial, or presentation of sorts. If a flagship university system can be won over, the thinking goes, other powerful institutions—including those with equally progressive reputations—might feel pressure to follow suit."After I present to them, they have to decide what to do," said Robert May, chair of the University of California's Academic Senate and a professor of philosophy and linguistics at UC-Davis. "They can act upon it, or they can ignore it."In other words, as with most things in modern academia, it's messy.

"But what's most significant about us is that we [would] by far be the largest institution to do it," added John Foran, a professor of sociology and environmental studies at UC-Santa Barbara, who co-wrote the argument in favor of divestment that circulated among faculty.After all, if the state's elite public college system made such a move, it wouldn't be first—or even close. In fact, this journey "has been going on for seven years," according to Emily Williams, a PhD student in geography at UC-Santa Barbara, who was most active in the campaign as an undergraduate, from 2012 to 2016. That roughly tracks with the progress of the national divestment movement, one that gained steam as the climate crisis came into sharper focus.The UC battle has been especially difficult because it required the coordination of the public university's sprawling network of campuses, organizations, and bureaucracies across a state with an economy larger than that of many countries. Activists were also coming up against a vague sense on part of students and others in the community that, well, they were California: What kind of divestment was even necessary, given their state's relatively hawkish climate policies?"A lot of people just don't think that this university that claims to be one of the greenest campuses in the United States had these massive investments in these dirty companies," Williams said.Divestment is also sometimes dismissed as a pretty symbolic gesture, in that it's not going to necessarily topple the oil industry. But advocates are quick to argue that doesn't mean it won't have a significant impact on broader policies, now and in the future."This is a political tactic for the university to make a social and moral statement, and it's not going to bankrupt Big Oil, but that's not the point," said Sydney Tinker Quynn, a rising senior at UC-Santa Cruz, who has for almost the past three years been a student organizer for Fossil Free UC, one of the campus groups campaigning for divestment.In the Chronicle of Higher Education, Christiana Figueres and Bill McKibben, two well-known climate change experts, wrote that "the fossil-fuel-divestment movement has become the biggest campaign of its kind in history, surpassing even the effort that Nelson Mandela credited with helping end South African apartheid a generation ago." (Middlebury, where McKibben is a scholar in residence, announced it would slowly divest in February.)Its impact isn't purely symbolic, either."Divestment helps to revoke the social license of fossil fuel companies, which they need to lobby against action on climate change," said Paul Ferraro, a professor of business and engineering at Johns Hopkins University. "Divestment helps by changing social norms about who ought to have a voice in politics. In other words, it helps turn fossil fuel companies into social pariahs and thereby revoke their social license to thwart political solutions to climate change."For their part, Figueres and McKibben noted back in April that "endowments and portfolios worth $8 trillion have divested in whole or in part of their holdings in coal, gas, and oil," and that "nearly 50 [colleges] in the United States have committed to divestment." Divesting from Big Tobacco and companies doing business with South Africa during Apartheid usually draw the most comparisons, and activists use these instances to show that there is a historical precedent for creating such a shift in opinion that is subsequently followed by more systemic changes.

Advertisement

"But what's most significant about us is that we [would] by far be the largest institution to do it," added John Foran, a professor of sociology and environmental studies at UC-Santa Barbara, who co-wrote the argument in favor of divestment that circulated among faculty.After all, if the state's elite public college system made such a move, it wouldn't be first—or even close. In fact, this journey "has been going on for seven years," according to Emily Williams, a PhD student in geography at UC-Santa Barbara, who was most active in the campaign as an undergraduate, from 2012 to 2016. That roughly tracks with the progress of the national divestment movement, one that gained steam as the climate crisis came into sharper focus.The UC battle has been especially difficult because it required the coordination of the public university's sprawling network of campuses, organizations, and bureaucracies across a state with an economy larger than that of many countries. Activists were also coming up against a vague sense on part of students and others in the community that, well, they were California: What kind of divestment was even necessary, given their state's relatively hawkish climate policies?

Advertisement

Advertisement

There have been some notable successes. In 2015, Syracuse University moved to divest $1.8 billion of its endowment from fossil fuel companies. But whereas Amherst in Massachusetts has pledged to be carbon neutral by 2030, and Stanford shed coal-mining stocks in 2014 (UC actually did something similar a year later), Swarthmore—where this national movement has some of its roots—has yet to divest.Meanwhile, student activists of Divest Harvard want the Ivy League school to divulge what exactly it's been investing in—and if its portfolio includes, as they suspect, a generous slice of fossil fuel companies, to change course immediately. They've been met with resistance from the administration as recently as April, when the university president showed up at a forum and said, "The day after, if we were to divest, we're still going to turn on the lights. We would still be dependent on fossil fuels."So the fight, as they say, continues."As long as our institutions of higher education continue to propagate business as usual, they remain complicit in the climate crisis," said Ilana Cohen, one of the lead coordinators of the Divest Harvard campaign. "And complicity is culpability."Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.Follow Alex Norcia on Twitter.