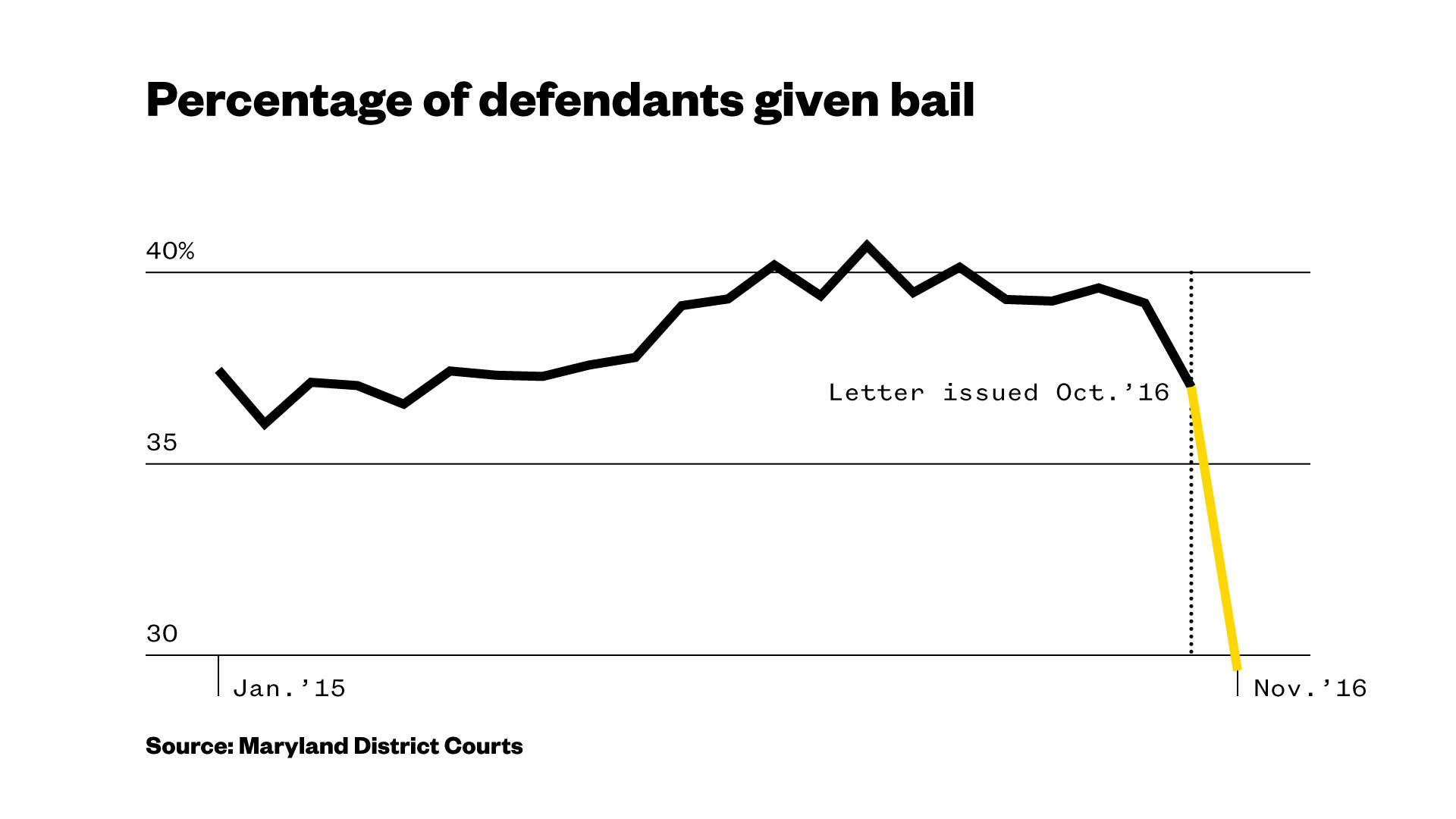

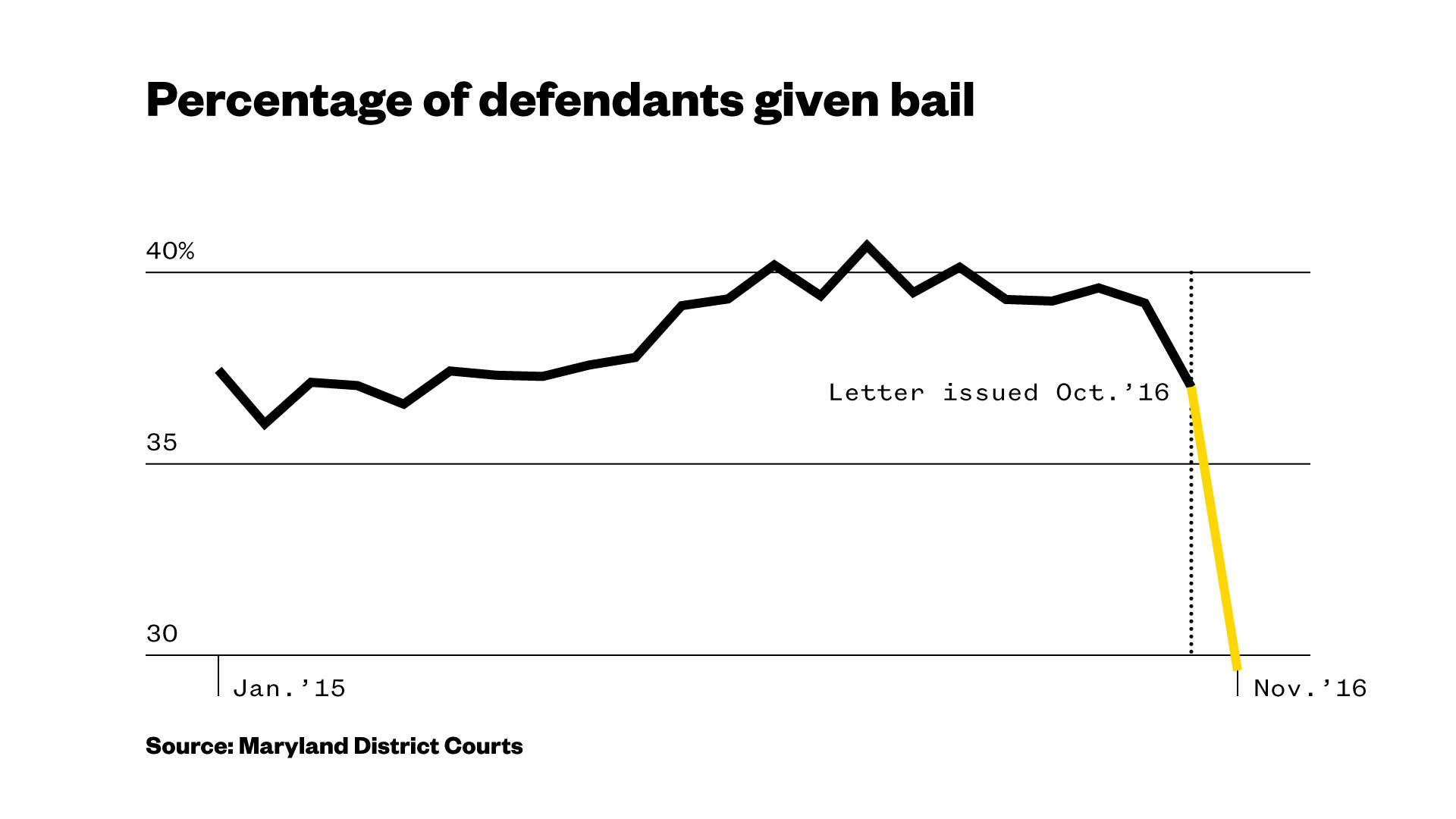

Worried she wouldn’t have much to give her children for Christmas, Shannan Wise, a 27-year-old single mom from Baltimore, struggled to get into the holiday spirit this past year. “It’s just bill after bill,” she said. “I can’t handle this bill, I can’t handle that.”A year earlier, Wise was waiting in a Baltimore jail cell with no clue how to pay her bail. She had been arrested and charged with a first degree assault — which she denied committing — after a confrontation with her sister. A judge set her bail at $100,000, a sum far out of reach for someone working two temp jobs and attending medical-billing school, even though her friends and family scrambled to help. A bondsman eventually agreed to bail Wise out in exchange for a series of nonrefundable payments totaling $10,000, or 10 percent of her bail.Wise’s story kicked off a six-hour hearing at the Maryland Court of Appeals on Jan. 12. A week earlier, Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh and former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder implored the seven judges to confirm a Judiciary Rules Committee rule requiring that judges stop setting bail amounts they know defendants cannot afford to pay. Since most states enact bail reform by changing laws, not judicial rules, Maryland’s approach is a unique, and controversial, attempt to lower the cost of bail.The way bail is administered in Maryland is “not in compliance with Maryland law, probably not in compliance with [Maryland’s] Constitution or the U.S. Constitution,” Frosh said. “People’s due process is being violated simply because they’re held in jail because they don’t have enough money.”This segment originally aired Jan. 4, 2017 on VICE News Tonight on HBO. At any given time, approximately 7,000 people are waiting in Maryland jails for their trial, unable to make bail, according to the 2014 Maryland Pretrial Risk Assessment Data Collection Study. Nationwide, the Department of Justice estimates that between 60 and 90 percent of the 745,000 inmates in county jails across the country are there for the same reason. These issues also disproportionately impact communities of color. According to “The High Cost of Bail,” a study published by the Maryland Office of the Public Defender in November 2016, black defendants in Maryland were charged bail premiums of at least $181 million between 2011 and 2015, while defendants of all other races combined were charged $75 million. In that same period, $75 million in bail bond premiums were charged in cases where the defendant was deemed innocent.In the past few decades, Bail reform has trickled through state legislatures across the United States. Kentucky, Colorado, Nevada, Hawaii, New Jersey, Vermont, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C., have all questioned the appropriateness of wealth-based incentives in the justice system and acted to pass legislation that reduces or removes cash bail. But these states also invest in pretrial alternatives like risk assessment tools that help determine which defendants are safe to release; systemized check-ins, like drug tests; and probationary officers for defendants who may need supervision or assistance. The added taxpayer costs often make bail reform laws unpopular and hard to pass.The proposed judicial rule change in Maryland bypasses the legislature, and thus, much of the opposition, although lawmakers would likely still have to pass legislation to support pretrial alternatives. Only a majority of the seven judges on the court of appeals would need to vote in favor of the change for it to pass. Several defense attorneys and public defenders in Maryland described the tactic as necessary in a state where bondsmen wine and dine the lawmakers who would be responsible for reform. Bondsmen, however, think the rule change is a slick way of avoiding the proper legislative process.“It’s called jamming it,” according to Vinnie Magliano, president of East Coast Bail Bonds and one of roughly 15,000 bond agents in the U.S. collectively handling about $14 billion every year. “If you took [bail reform] to a vote, the citizens of the state of Maryland would overwhelmingly not go for this if it was explained to them right.”But any taxpayer-cost calculations should also account for the high cost of incarceration. Pretrial services that offset high bonds cost between $2.50 and $10 a day per person, according to Frosh, as opposed to the $83-153 price tag to hold someone in jail. “Not only are we ruining [defendants’] lives, we’re doing it at great expense to the taxpayers,” he said.Magliano has written bonds for Baltimore-area defendants for over a decade. He argues that demanding high bail makes cities like Baltimore safer by acting as a deterrent for crime, making reentry into the community before trial harder for criminals, and putting a financial incentive on cooperating with the courts. “Nobody’s ever saying anything about a victim, not one person cares about the people who live in this state,” he said. “It’s all about the poor people. It’s like we’re battling for the criminals.”After over six hours of testimony from lawyers, bondsmen, and community members, the bail hearing in Maryland ended with only three of the seven appellate judges voting in favor of an initial motion to adopt the rule change. The rest were unprepared to act without additional planning, and many suggested the rule change alone was an insufficient guide to completely overhaul the bail system. The court will meet again on Feb. 7 to reconsider bail reform, but signs of change, even without the judge’s validation, have already appeared. Judges set bail 26% less often after October, according to a review of the District Court Commissioner’s case data. That was the month Attorney General Frosh initially warned the judges of his constitutional concerns.

At any given time, approximately 7,000 people are waiting in Maryland jails for their trial, unable to make bail, according to the 2014 Maryland Pretrial Risk Assessment Data Collection Study. Nationwide, the Department of Justice estimates that between 60 and 90 percent of the 745,000 inmates in county jails across the country are there for the same reason. These issues also disproportionately impact communities of color. According to “The High Cost of Bail,” a study published by the Maryland Office of the Public Defender in November 2016, black defendants in Maryland were charged bail premiums of at least $181 million between 2011 and 2015, while defendants of all other races combined were charged $75 million. In that same period, $75 million in bail bond premiums were charged in cases where the defendant was deemed innocent.In the past few decades, Bail reform has trickled through state legislatures across the United States. Kentucky, Colorado, Nevada, Hawaii, New Jersey, Vermont, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C., have all questioned the appropriateness of wealth-based incentives in the justice system and acted to pass legislation that reduces or removes cash bail. But these states also invest in pretrial alternatives like risk assessment tools that help determine which defendants are safe to release; systemized check-ins, like drug tests; and probationary officers for defendants who may need supervision or assistance. The added taxpayer costs often make bail reform laws unpopular and hard to pass.The proposed judicial rule change in Maryland bypasses the legislature, and thus, much of the opposition, although lawmakers would likely still have to pass legislation to support pretrial alternatives. Only a majority of the seven judges on the court of appeals would need to vote in favor of the change for it to pass. Several defense attorneys and public defenders in Maryland described the tactic as necessary in a state where bondsmen wine and dine the lawmakers who would be responsible for reform. Bondsmen, however, think the rule change is a slick way of avoiding the proper legislative process.“It’s called jamming it,” according to Vinnie Magliano, president of East Coast Bail Bonds and one of roughly 15,000 bond agents in the U.S. collectively handling about $14 billion every year. “If you took [bail reform] to a vote, the citizens of the state of Maryland would overwhelmingly not go for this if it was explained to them right.”But any taxpayer-cost calculations should also account for the high cost of incarceration. Pretrial services that offset high bonds cost between $2.50 and $10 a day per person, according to Frosh, as opposed to the $83-153 price tag to hold someone in jail. “Not only are we ruining [defendants’] lives, we’re doing it at great expense to the taxpayers,” he said.Magliano has written bonds for Baltimore-area defendants for over a decade. He argues that demanding high bail makes cities like Baltimore safer by acting as a deterrent for crime, making reentry into the community before trial harder for criminals, and putting a financial incentive on cooperating with the courts. “Nobody’s ever saying anything about a victim, not one person cares about the people who live in this state,” he said. “It’s all about the poor people. It’s like we’re battling for the criminals.”After over six hours of testimony from lawyers, bondsmen, and community members, the bail hearing in Maryland ended with only three of the seven appellate judges voting in favor of an initial motion to adopt the rule change. The rest were unprepared to act without additional planning, and many suggested the rule change alone was an insufficient guide to completely overhaul the bail system. The court will meet again on Feb. 7 to reconsider bail reform, but signs of change, even without the judge’s validation, have already appeared. Judges set bail 26% less often after October, according to a review of the District Court Commissioner’s case data. That was the month Attorney General Frosh initially warned the judges of his constitutional concerns. The charges against Wise were dropped, and she’s no longer paying off her bail. But in the months it took to resolve her case, she struggled to reimburse the family members and friends who fronted her bail bond, fell behind on her coursework, and lost out on a job opportunity from an employer displeased that she had a court date.“Me, a single mother working hard, trying to go to school, complete on making something out of herself, to be a better role model for her children — we’re gonna keep her in here. ‘Cause they know half of the time that low-income families, they don’t have [the money],” Wise said. “They don’t care. ‘Let’s throw them to the wolves.’”

The charges against Wise were dropped, and she’s no longer paying off her bail. But in the months it took to resolve her case, she struggled to reimburse the family members and friends who fronted her bail bond, fell behind on her coursework, and lost out on a job opportunity from an employer displeased that she had a court date.“Me, a single mother working hard, trying to go to school, complete on making something out of herself, to be a better role model for her children — we’re gonna keep her in here. ‘Cause they know half of the time that low-income families, they don’t have [the money],” Wise said. “They don’t care. ‘Let’s throw them to the wolves.’”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement