Interview By Milene LarssonImages Courtesy of The Ingmar Bergman Foundation “This is a 12-year-old Ingmar with his legendary first film camera, the Laterna Magica. He used to say, ‘My life as a filmmaker begun when I got the Laterna Magica,’ and he named his autobiography after it. Apparently, it was given to his brother for Christmas and Ingmar had gotten tin soldiers but then they switched gifts.”When Ingmar Bergman was 20 years old, he faced a fairly ordinary existential predicament: What’s a guy to do with a head full of thoughts he can neither comprehend nor control? His answer: “You open the gas stove at home in the little kitchen and then it’ll all blow up. Boom!” Luckily for two generations of film crazies, he came to his senses and spared his kitchen the embarrassment of a floor coated in burnt brain-goo. Instead he became one of the greatest artists in the history of cinema.Bergman’s 50 films dealt with beauty and treachery, God and Satan, and nearly every complex thought in between (including a crush on his mom). Over that time, he stuffed a secret room at his house on Fårö with a massive archive of his early notebooks, manuscripts, letters, photos, and miscellany—all of which turned out to have a direct relation to his closely studied oeuvre. To prevent his booty from being looted and sold off at auction to some rich collector after his demise—which is currently happening to the rest of his private belongings— Bergman entrusted this secret archive to film professor Maaret Koskinen, who methodically dissected it for rich new perspective. It can’t be too surprising to Bergman enthusiasts that much of the stuff Koskinen unearthed casts an awkward and indelible shadow over the man and his work. She was kind enough to sit with us for a while, chat, and walk us through a juicy visual Bergman smorgasbord.Vice: Why did Ingmar Bergman trust you with this most private archive?Maaret Koskinen: I was one of the few people in Sweden at the time to have written anything about him. It was like everyone was waiting for him to die first, so I wrote my doctoral dissertation on his cinematic aesthetics. He appreciated it so much that he dug out my number, called me up, and we spoke for two hours. I was star struck.What was this conversation about?He had read the whole thing and started defending himself. He was impressed by me noticing the voyeur theme in his films and said, “Hell, you know, that’s exactly what my films are about—the other room! You’re in one room looking into another and I do that every night!” And then he told me, “I have this spot on my balcony where I can stand unseen and look in on other people’s daily life in their kitchen or living room. I find it more fascinating than anything.”He was a peeping tom!Then I didn’t hear from him for five years until he called me up again and said, “Hey, listen: There’s a room here on Fårö, it’s five times five-square-meters and in it I’ve amassed all kinds of things. In fact it’s a hell of a mess. Would you like to take a look at it?” As you can imagine, it was an offer I couldn’t refuse.In an early notebook from ’38 you found a diary entry in which he wanted to blow his brains out. Where do you think that existential angst and self-hatred came from?He had a dominating mother and his father was a priest who brought him up according to a hierarchic method where the kids were at the bottom. Not ideal for someone unable to control his sudden furious outbursts—he wasn’t given the epithet “demon director” for nothing. He threw hammers around and he also had a strong sex drive, which didn’t go down well with his parents. I tried not to have any preconceived notions, but reading his early writings it’s obvious that he found his thematic sphere early on through his family relations—family, sexuality, religion, and God. His own family was a hot house in that respect.Why did it take so long for Sweden to acknowledge him?Before making the intellectual TV soapScenes from a Marriagein ’73, the general public didn’t understand him at all. That bastard Bergman was questioning whether God exists when God had already been eradicated. It drove people mad because, in their eyes, he was digging into stuff that didn’t matter anymore. But what made him controversial in Sweden, those “irrelevant matters,” were matters that other countries hadn’t gotten rid of.So you think it was, ironically, Bergman’s religious curiosity in this vastly secular country that made him world-famous?Definitely. He was one of the few directors to put God on the cinematic world map. During his heyday,The Seventh Sealwas played three times a day in the States, making it one of the most played movies on the North American continent. Another thing, appreciated by the French in particular, was how honest and open he was about sexual relations. A lot of what was said and done in his early films were things you just didn’t say, like, “Men are just kids with big genitals.”You wrote a book about all the skeletons you dug out of his closet. It must have been nerve racking giving him the manuscript.I was facing the possibility of having spent years on something that might never get published. I remember giving him the manuscript to read over Easter and then I went on a ski vacation without a cell phone. He dug out my husband’s cell phone number and called me up all distraught and you could hear on his voice that he was literally shaking, “I’ve read your script and I’m not even able to talk now. We will have to talk about it tomorrow. Call me on a steady line.” When we spoke the next day he told me, “I’m in shock. This is an autopsy, a close-up of a relative I’d rather not be acquainted with.” Still he let me publish the book without changing a word.If you’re Swedish you can read more on Maaret Koskinen’s findings in her bookI Begynnelsen Var Ordet(In the Beginning Was the Word). Her upcoming bookIngmar Bergman’s The Silencewill be out later this fall. For more information about these images, visit Ingmarbergman.se

“This is a 12-year-old Ingmar with his legendary first film camera, the Laterna Magica. He used to say, ‘My life as a filmmaker begun when I got the Laterna Magica,’ and he named his autobiography after it. Apparently, it was given to his brother for Christmas and Ingmar had gotten tin soldiers but then they switched gifts.”When Ingmar Bergman was 20 years old, he faced a fairly ordinary existential predicament: What’s a guy to do with a head full of thoughts he can neither comprehend nor control? His answer: “You open the gas stove at home in the little kitchen and then it’ll all blow up. Boom!” Luckily for two generations of film crazies, he came to his senses and spared his kitchen the embarrassment of a floor coated in burnt brain-goo. Instead he became one of the greatest artists in the history of cinema.Bergman’s 50 films dealt with beauty and treachery, God and Satan, and nearly every complex thought in between (including a crush on his mom). Over that time, he stuffed a secret room at his house on Fårö with a massive archive of his early notebooks, manuscripts, letters, photos, and miscellany—all of which turned out to have a direct relation to his closely studied oeuvre. To prevent his booty from being looted and sold off at auction to some rich collector after his demise—which is currently happening to the rest of his private belongings— Bergman entrusted this secret archive to film professor Maaret Koskinen, who methodically dissected it for rich new perspective. It can’t be too surprising to Bergman enthusiasts that much of the stuff Koskinen unearthed casts an awkward and indelible shadow over the man and his work. She was kind enough to sit with us for a while, chat, and walk us through a juicy visual Bergman smorgasbord.Vice: Why did Ingmar Bergman trust you with this most private archive?Maaret Koskinen: I was one of the few people in Sweden at the time to have written anything about him. It was like everyone was waiting for him to die first, so I wrote my doctoral dissertation on his cinematic aesthetics. He appreciated it so much that he dug out my number, called me up, and we spoke for two hours. I was star struck.What was this conversation about?He had read the whole thing and started defending himself. He was impressed by me noticing the voyeur theme in his films and said, “Hell, you know, that’s exactly what my films are about—the other room! You’re in one room looking into another and I do that every night!” And then he told me, “I have this spot on my balcony where I can stand unseen and look in on other people’s daily life in their kitchen or living room. I find it more fascinating than anything.”He was a peeping tom!Then I didn’t hear from him for five years until he called me up again and said, “Hey, listen: There’s a room here on Fårö, it’s five times five-square-meters and in it I’ve amassed all kinds of things. In fact it’s a hell of a mess. Would you like to take a look at it?” As you can imagine, it was an offer I couldn’t refuse.In an early notebook from ’38 you found a diary entry in which he wanted to blow his brains out. Where do you think that existential angst and self-hatred came from?He had a dominating mother and his father was a priest who brought him up according to a hierarchic method where the kids were at the bottom. Not ideal for someone unable to control his sudden furious outbursts—he wasn’t given the epithet “demon director” for nothing. He threw hammers around and he also had a strong sex drive, which didn’t go down well with his parents. I tried not to have any preconceived notions, but reading his early writings it’s obvious that he found his thematic sphere early on through his family relations—family, sexuality, religion, and God. His own family was a hot house in that respect.Why did it take so long for Sweden to acknowledge him?Before making the intellectual TV soapScenes from a Marriagein ’73, the general public didn’t understand him at all. That bastard Bergman was questioning whether God exists when God had already been eradicated. It drove people mad because, in their eyes, he was digging into stuff that didn’t matter anymore. But what made him controversial in Sweden, those “irrelevant matters,” were matters that other countries hadn’t gotten rid of.So you think it was, ironically, Bergman’s religious curiosity in this vastly secular country that made him world-famous?Definitely. He was one of the few directors to put God on the cinematic world map. During his heyday,The Seventh Sealwas played three times a day in the States, making it one of the most played movies on the North American continent. Another thing, appreciated by the French in particular, was how honest and open he was about sexual relations. A lot of what was said and done in his early films were things you just didn’t say, like, “Men are just kids with big genitals.”You wrote a book about all the skeletons you dug out of his closet. It must have been nerve racking giving him the manuscript.I was facing the possibility of having spent years on something that might never get published. I remember giving him the manuscript to read over Easter and then I went on a ski vacation without a cell phone. He dug out my husband’s cell phone number and called me up all distraught and you could hear on his voice that he was literally shaking, “I’ve read your script and I’m not even able to talk now. We will have to talk about it tomorrow. Call me on a steady line.” When we spoke the next day he told me, “I’m in shock. This is an autopsy, a close-up of a relative I’d rather not be acquainted with.” Still he let me publish the book without changing a word.If you’re Swedish you can read more on Maaret Koskinen’s findings in her bookI Begynnelsen Var Ordet(In the Beginning Was the Word). Her upcoming bookIngmar Bergman’s The Silencewill be out later this fall. For more information about these images, visit Ingmarbergman.se “Young Ingmar Bergman enjoying a book. He later denounced literature, claiming he was a man of the cinema when in fact he was a frustrated writer. He always said he didn’t read much but you can tell from his language that he did, and if you read his scripts they’re like novels, describing scents, people’s appearances, and ambiences—totally irrelevant information for a film script. That’s why I named my Fårö archive book In the Beginning Was the Word: It was his longing to be a respected writer that drove him. He was shocked when he read it and discovered that was actually the case. He got good at writing in the end and it must have been a sweet revenge to have the big publishing houses fight to put out his books.”

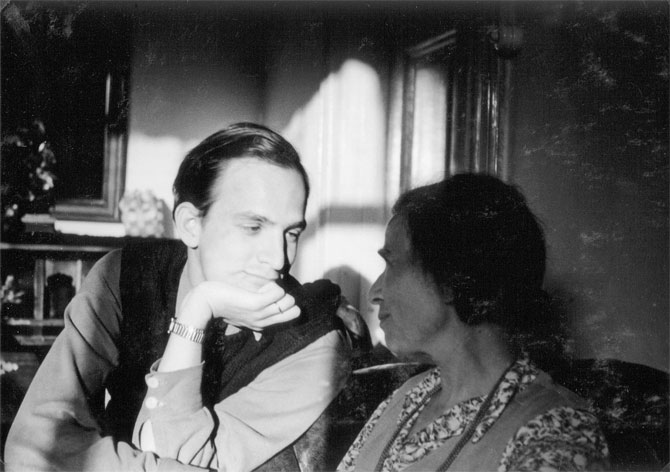

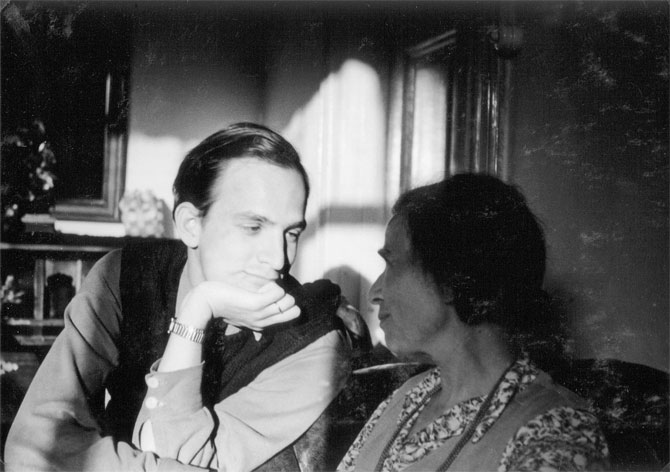

“Young Ingmar Bergman enjoying a book. He later denounced literature, claiming he was a man of the cinema when in fact he was a frustrated writer. He always said he didn’t read much but you can tell from his language that he did, and if you read his scripts they’re like novels, describing scents, people’s appearances, and ambiences—totally irrelevant information for a film script. That’s why I named my Fårö archive book In the Beginning Was the Word: It was his longing to be a respected writer that drove him. He was shocked when he read it and discovered that was actually the case. He got good at writing in the end and it must have been a sweet revenge to have the big publishing houses fight to put out his books.” “This is Ingmar Bergman with his mother. Above all devils, girls, and whatever else was occupying his thoughts, she was dominant both in his private life and in his writing. It’s weirdly ambivalent as she sometimes turns into a desired female figure. In one of his manuscripts I found a part where a boy is looking at his mother and checking out her breasts, and it gets very strange and suggestive. After his mother passed away he found out that she had had an affair with a younger man, which laid the foundation to his films The Best Intentions and Private Confessions.”

“This is Ingmar Bergman with his mother. Above all devils, girls, and whatever else was occupying his thoughts, she was dominant both in his private life and in his writing. It’s weirdly ambivalent as she sometimes turns into a desired female figure. In one of his manuscripts I found a part where a boy is looking at his mother and checking out her breasts, and it gets very strange and suggestive. After his mother passed away he found out that she had had an affair with a younger man, which laid the foundation to his films The Best Intentions and Private Confessions.” “These little devils are from one of his earliest diaries. When I stayed at his house on Fårö I found devils all over the place. He had drawn them directly on the wallpaper, the fridge, and by the lamp switches there were little devils next to the words, “Turn off the lights!” If you look at them closely they seem happy and like they’re in uprising: little rebels about to mess up the system. In most of his early 40s movies there’s a character called Jack—a sort of marionette manipulator, a young guy who is consciously causing trouble for other people. It was probably a young alter ego that Bergman identified with. He was ruthless. His wives often accused him of that and he also accused himself of being merciless in his hunt for whatever occupied him for the moment.”

“These little devils are from one of his earliest diaries. When I stayed at his house on Fårö I found devils all over the place. He had drawn them directly on the wallpaper, the fridge, and by the lamp switches there were little devils next to the words, “Turn off the lights!” If you look at them closely they seem happy and like they’re in uprising: little rebels about to mess up the system. In most of his early 40s movies there’s a character called Jack—a sort of marionette manipulator, a young guy who is consciously causing trouble for other people. It was probably a young alter ego that Bergman identified with. He was ruthless. His wives often accused him of that and he also accused himself of being merciless in his hunt for whatever occupied him for the moment.” “Karin Lannby on the right was his first big love. His family didn’t approve of her so he ran away from home and didn’t come back for four years. She was a free spirit who’d taken part in founding the radical leftwing student movement in Sweden and was also a published poet with an intellectual genius who taught him a lot and was of great importance both to his personal and professional development. She became a theme in many of his early movies, like her man-eating alter ego Rut in Woman Without a Face. After breaking up with her he had his first big creative outburst, maybe in competition as she’d been both published and reviewed and was the kind of writer he wanted to match himself with.”

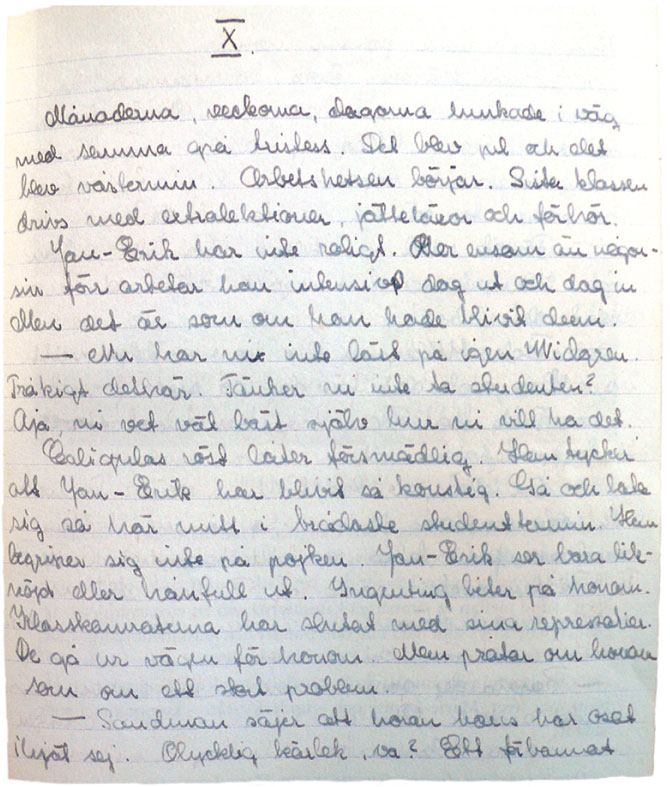

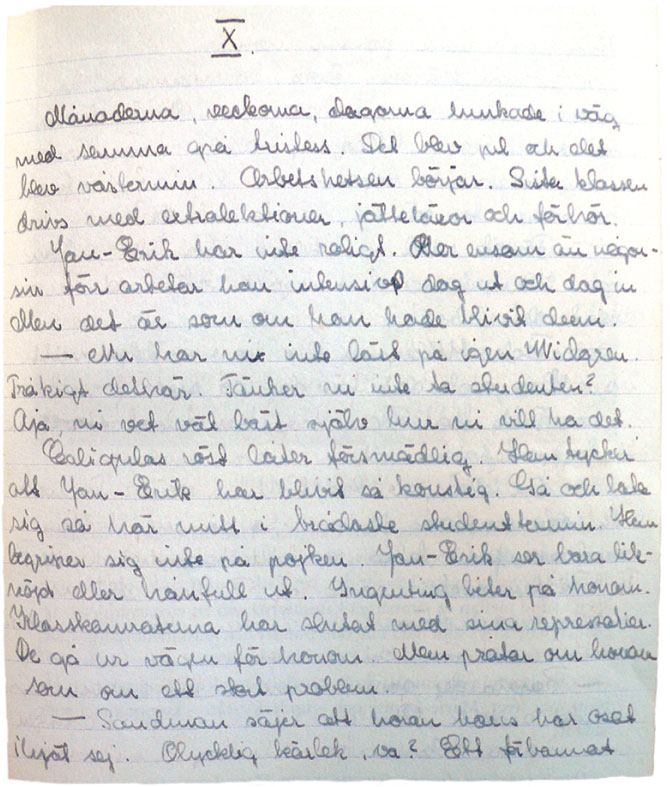

“Karin Lannby on the right was his first big love. His family didn’t approve of her so he ran away from home and didn’t come back for four years. She was a free spirit who’d taken part in founding the radical leftwing student movement in Sweden and was also a published poet with an intellectual genius who taught him a lot and was of great importance both to his personal and professional development. She became a theme in many of his early movies, like her man-eating alter ego Rut in Woman Without a Face. After breaking up with her he had his first big creative outburst, maybe in competition as she’d been both published and reviewed and was the kind of writer he wanted to match himself with.” “This is an excerpt from the first draft of Frenzy, his cinematic debut in ’44. He wrote it the year after his graduation and there are all kinds of biographical details in it, like the protagonist drawing little devils, his family situation, and his life in Stockholm. If you compare it to the final manuscript for the film that came out six years later, you can see how he’s altered and censored the original script. The first version was much closer to a raw reality dealing with abortion and binge-drinking orgies when the parents were away. He washed his manuscripts in a similar way all through his career but not as visibly.”

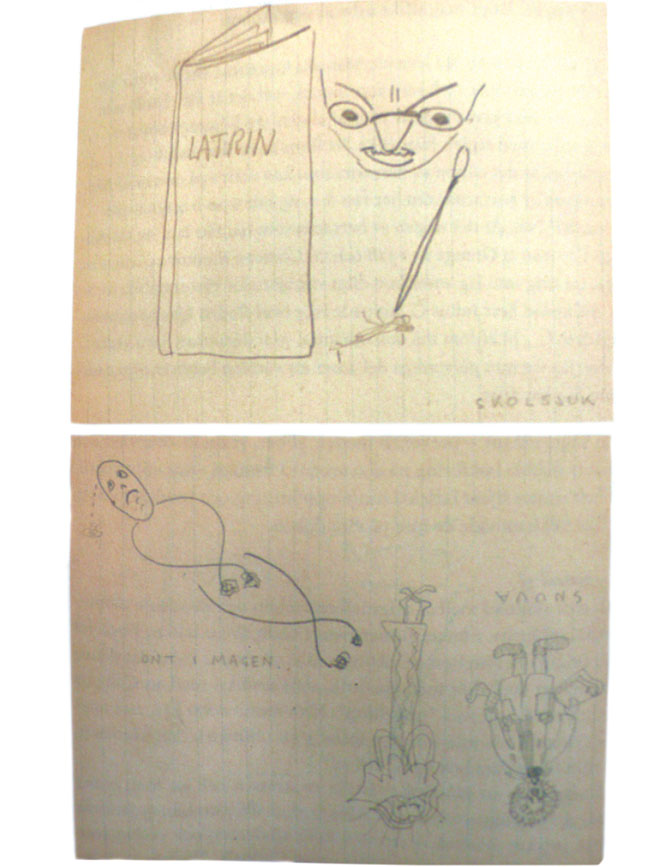

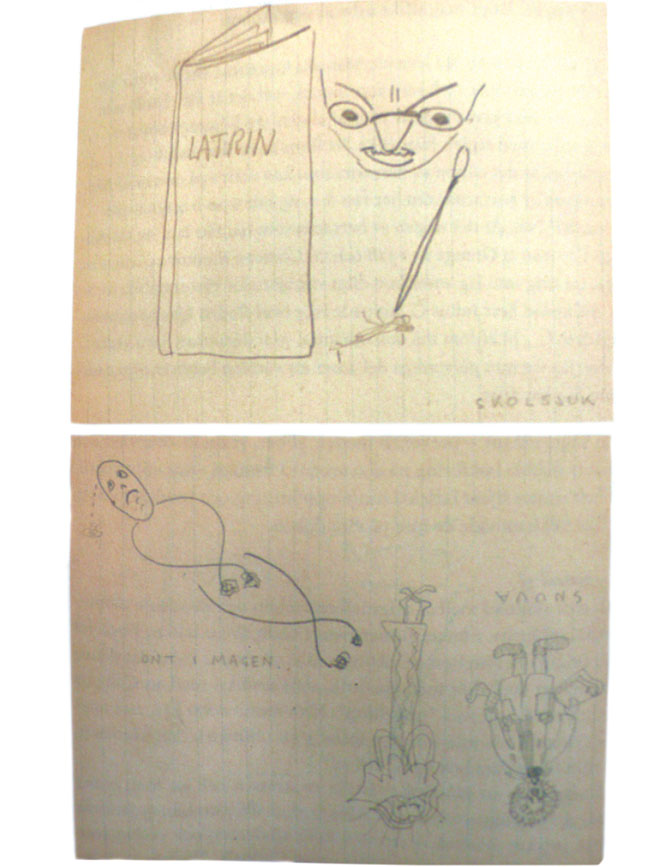

“This is an excerpt from the first draft of Frenzy, his cinematic debut in ’44. He wrote it the year after his graduation and there are all kinds of biographical details in it, like the protagonist drawing little devils, his family situation, and his life in Stockholm. If you compare it to the final manuscript for the film that came out six years later, you can see how he’s altered and censored the original script. The first version was much closer to a raw reality dealing with abortion and binge-drinking orgies when the parents were away. He washed his manuscripts in a similar way all through his career but not as visibly.” “These drawings accompanied the first Frenzy draft, in which he looked back at the school experience as being in a fascistic hierarchic system. “Latrin” means lavatory and outside of it lays a poor, dehydrated student with that terrible teacher’s face looking down and pointing his stick at him. “Skolsjuk” and “ont i magen” means school sick and stomach ache—Bergman famously suffered from stomach aches due to angst throughout his life. His mother’s diaries and his mentors’ notes all say he was the teacher’s pet, which doesn’t mean that he didn’t indeed hate school, and like most young men at that time he wanted to be seen as a rebel that went against the system.”

“These drawings accompanied the first Frenzy draft, in which he looked back at the school experience as being in a fascistic hierarchic system. “Latrin” means lavatory and outside of it lays a poor, dehydrated student with that terrible teacher’s face looking down and pointing his stick at him. “Skolsjuk” and “ont i magen” means school sick and stomach ache—Bergman famously suffered from stomach aches due to angst throughout his life. His mother’s diaries and his mentors’ notes all say he was the teacher’s pet, which doesn’t mean that he didn’t indeed hate school, and like most young men at that time he wanted to be seen as a rebel that went against the system.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement