Casey Johnston

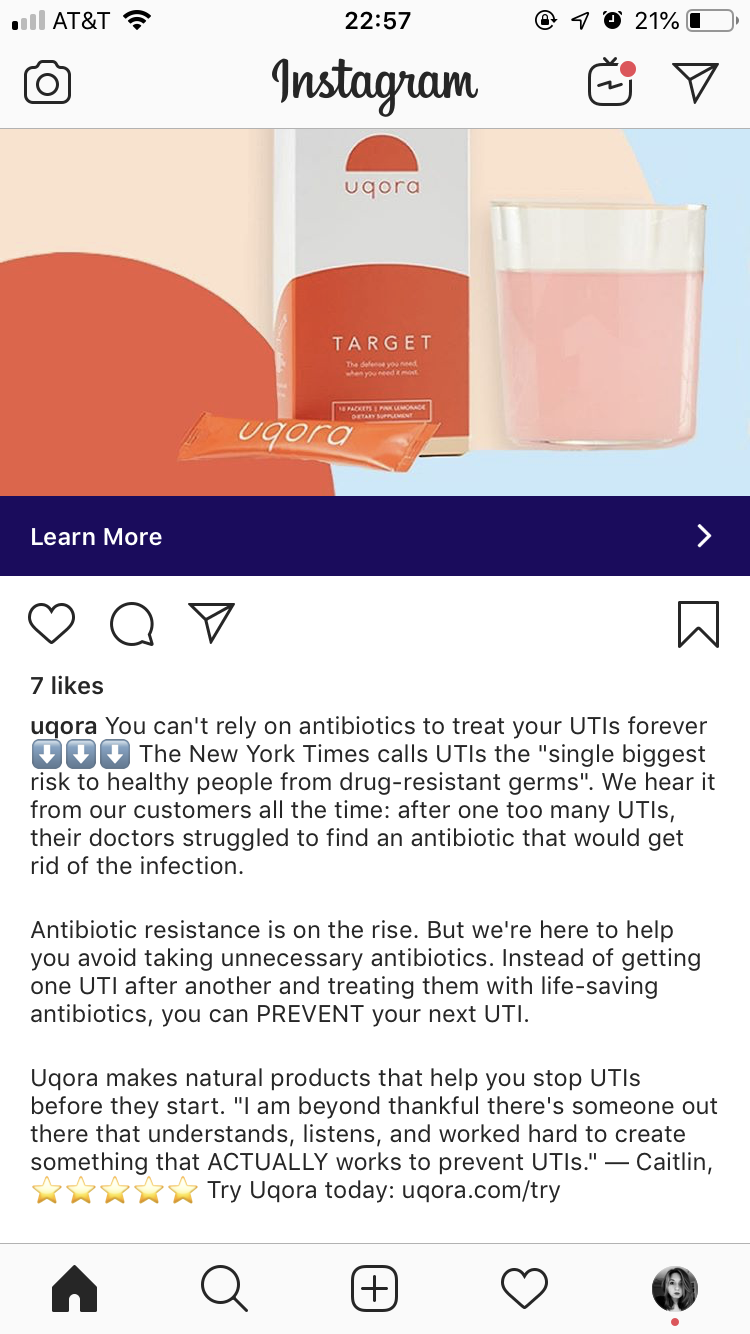

If you have a vagina, the chances are you’ve experienced the misery of a urinary tract infection (UTI). You’ll know that burning, aching pain, and the constant feeling of needing to pee. You might also have to be extra careful about sex, and make a point of leaping up to go to the bathroom right after—just another fun way that sex can be painful and dangerous for people with vaginas. About 30-40 percent of people with vaginas who get a UTI will get another one within a few months, and for some, they become a chronic problem.So if you’ve seen the ads on TV or Instagram for Uqora, the “UTI Prevention Company” that sells products it claims will “prevent your next UTI,” you might be tempted. Thanks to America’s appalling healthcare system, millions of uninsured or underinsured people can’t afford to see a doctor, or don’t have one they trust. It’s easy to imagine how a few taps on the iPhone and the price of a co-pay at the doctor’s office—without the hassle of actually going—might entice UTI sufferers to try Uqora.But appealing as it seems, the claim that Uqora can prevent a UTI is troubling. It’s not just claiming to “help” prevent your next UTI, like how your shampoo claims to “help prevent flakes,” but to fully prevent it, period. Because Uqora’s products are dietary supplements and not drugs, these claims fall into a legal and ethical gray area: Bold claims like that are meant to be reserved for drugs that have been FDA-approved, which Uqora’s products haven’t. Yet Uqora, and thousands of other dietary supplement companies, benefit from laws that make it all too easy to make these kinds of boundary-pushing claims. An Instagram ad for Uqora products, served to the author. Photo by Libby WatsonUqora makes three products: Target, a powder added to water that’s meant to be taken after sex or every three days; Control, a pill meant to be taken daily if you “aren't always sure what causes your UTI”; and Promote, a probiotic pill to restore good bacteria after a course of antibiotics, the usual treatment for a UTI (which is causing problems with growing antibiotic resistance). Target and Control contain d-mannose, a type of naturally-occurring sugar that has been shown in some trials to possibly reduce the chance of UTIs by binding to bacteria that cause them, often E. coli, and helping flush it out in the stream of urine. Target also contains vitamins and minerals, like Vitamin B6, meant to act as a diuretic, and Control contains other natural plant extracts that Uqora claims will help with UTIs, like curcumin (found in turmeric) and black pepper extracts. Each product costs $30 for a 30 day supply.Uqora isn’t alone in the medicine-via-Instagram market. Mail-order prescription drug services like Hers, Hims, and Roman flood the platform with ads, selling things like birth control, erectile dysfunction meds, and blood pressure drugs used to treat performance anxiety. These provide a younger, debt-laden audience with an easier way to get the drugs they believe they need, even if it ends up being with a questionable level of medical guidance.

An Instagram ad for Uqora products, served to the author. Photo by Libby WatsonUqora makes three products: Target, a powder added to water that’s meant to be taken after sex or every three days; Control, a pill meant to be taken daily if you “aren't always sure what causes your UTI”; and Promote, a probiotic pill to restore good bacteria after a course of antibiotics, the usual treatment for a UTI (which is causing problems with growing antibiotic resistance). Target and Control contain d-mannose, a type of naturally-occurring sugar that has been shown in some trials to possibly reduce the chance of UTIs by binding to bacteria that cause them, often E. coli, and helping flush it out in the stream of urine. Target also contains vitamins and minerals, like Vitamin B6, meant to act as a diuretic, and Control contains other natural plant extracts that Uqora claims will help with UTIs, like curcumin (found in turmeric) and black pepper extracts. Each product costs $30 for a 30 day supply.Uqora isn’t alone in the medicine-via-Instagram market. Mail-order prescription drug services like Hers, Hims, and Roman flood the platform with ads, selling things like birth control, erectile dysfunction meds, and blood pressure drugs used to treat performance anxiety. These provide a younger, debt-laden audience with an easier way to get the drugs they believe they need, even if it ends up being with a questionable level of medical guidance. Under the law and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations, dietary supplements that make certain claims about what their products do must include a disclaimer that the product is not intended to "diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease," because “only a drug can legally make such a claim,” according to the FDA. Uqora is not a drug, nor has it been through the approval process that a drug would go through. And yet, there the claim is, in all their marketing materials: Uqora will prevent your next UTI.Uqora’s websites—though not its ads—include the standard legal disclaimer for dietary supplements at the very bottom of the page, that its “statements have not been evaluated by the FDA” and the product “is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.” This is weird, because I am pretty sure describing yourself as “The UTI Prevention Company,” and claiming the product is “UTI prevention that works,” and that it will “prevent your next UTI,” are claims that the product will prevent disease.

Under the law and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations, dietary supplements that make certain claims about what their products do must include a disclaimer that the product is not intended to "diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease," because “only a drug can legally make such a claim,” according to the FDA. Uqora is not a drug, nor has it been through the approval process that a drug would go through. And yet, there the claim is, in all their marketing materials: Uqora will prevent your next UTI.Uqora’s websites—though not its ads—include the standard legal disclaimer for dietary supplements at the very bottom of the page, that its “statements have not been evaluated by the FDA” and the product “is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.” This is weird, because I am pretty sure describing yourself as “The UTI Prevention Company,” and claiming the product is “UTI prevention that works,” and that it will “prevent your next UTI,” are claims that the product will prevent disease. The homepage of Uqora's website.Thanks to a 1994 law introduced by Sen. Orrin Hatch, who represented the home state of many dietary supplement companies and took plenty of their money, manufacturers don’t have to prove that a supplement is effective in the way that prescription drugs do. Companies only need to state their supplement products have not been tested by the FDA, essentially telling consumers that it’s up to them to decide if the product works. Critics of the law describe this disclaimer as the “quack Miranda warning”—a meaningless phrase invoked automatically to mask a range of unsupported medical claims.In a statement, the FDA reiterated to me that “products claiming to cure, treat, mitigate, or prevent diseases are drugs—and are subject to all requirements that apply to drugs—even if they are represented as ‘dietary supplements,’” and added that while it wouldn’t comment on Uqora specifically, the agency is “authorized to take action against violative products.”When I asked Uqora about how it can make claims that are directly contradictory to the FDA disclaimer printed at the bottom of their site, co-founder Spencer Gordon told me that “dietary supplements sit in sort of a gray area between two regulatory bodies, the FDA and the FTC,” with “the FDA regulating product packaging and labeling, specifically, and the FTC regulating actual marketing claims.” This means, he argued, “as far as the FDA, our packaging doesn't say anything about prevent[ing] UTIs because that's not an approved FDA claim for the dietary ingredients inside the formula at this time.” To clarify, I asked if he meant that because packaging itself doesn’t make claims about preventing UTI, it doesn’t matter that all the marketing materials do make that claim; Gordon said that was correct. Presumably, Orrin Hatch would be thrilled to hear that Uqora remains free to make contradictory claims under the law he authored.But Gordon’s understanding doesn’t appear to be true: The FDA has sent many warning letters in the past to dietary supplement companies over online marketing, not just literal product packaging. In July, the FDA sent a warning letter to a company called Curaleaf for claims it made about its CBD products on its website, Facebook, and Twitter about being designed “for chronic pain” and aimed at “reduc[ing] anxiety symptoms.” Many other similar warning letters from the FDA cite website claims. The FTC does regulate marketing claims for supplements too, and neither the FDA nor FTC would comment on Uqora specifically, but even the logic of Gordon’s argument is strained: How would a consumer even see the packaging and labeling of an online product before they purchased it?This isn’t to say that Uqora necessarily does nothing. One 2014 randomized controlled trial published in the World Journal of Urology tested the same dose of d-mannose that Target contains on 308 people, and did find that it “significantly reduced the risk of recurrent UTI.” The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence said in 2018 that this 2014 trial provided “high quality” evidence for d-mannose’s effectiveness, and suggested that non-pregnant people with vaginas with recurrent UTIs “may wish to try D-mannose, as a self-care treatment,” but noted that the trial was “small.” In 2018, the American Urogynecologic Society’s Best Practice Statement for recurrent UTIs said there was “limited” evidence for d-mannose’s effectiveness. The same paper said there is “insufficient” evidence to recommend the use of Vitamin C, another ingredient in Uqora’s Target. As for curcumin, even a post on Uqora’s own site says turmeric is only “rumored” to prevent UTIs, and notes that “whether or not curcumin is effective at killing E. coli in humans is not certain, and requires more research.”Uqora keeps information sheets outlining the scientific basis for its claims that cite studies on the products’ various ingredients, such as one that shows curcumin can break up infection-causing “biofilms.” But there are no studies cited that demonstrate curcumin’s effectiveness in treating UTIs. Chris D’Adamo, the Director of Research at the Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Maryland who has served as principal investigator on many studies of dietary supplements, said the evidence Uqora offered was “pretty typical of the industry,” and that while it was “better than most companies,” Uqora was nonetheless “connecting some dots that aren’t really there.” The studies merely establish the mechanism by which the ingredient might work to prevent UTIs, not that they actually do.David Seres, director of medical nutrition and associate professor of medicine at the Institute of Human Nutrition, Columbia University Medical Center, said that Uqora’s arguments are “not medically credible without direct testing” of the actual product to make a prevention claim. Uqora is conducting a clinical trial of its products, but the results won’t start to become available until 2020; D’Adamo noted that the “study on their finished product would connect the dots and would be commendable.” Until then, the products are still on sale, still making the same claims.Uqora is hardly the worst offender in the dietary supplement industry. The law is set up to make it easy for companies to make claims that skirt the law, if not actively flout it, and the deluge of products making health and wellness claims online has shown that the FDA doesn’t have the capacity to go after most cases. And the industry has worse problems than misleading claims: The FDA’s own data shows that unapproved prescription drugs exist in 20 percent of dietary supplements. But the fact remains that Uqora is making a claim that it shouldn’t be making, and there’s a reason we’re meant to have laws in place to regulate the strongest claims about treating and preventing diseases, which is that we can’t trust companies to be responsible in making claims to sell products. Not even the ones with the best Instagram ads.

The homepage of Uqora's website.Thanks to a 1994 law introduced by Sen. Orrin Hatch, who represented the home state of many dietary supplement companies and took plenty of their money, manufacturers don’t have to prove that a supplement is effective in the way that prescription drugs do. Companies only need to state their supplement products have not been tested by the FDA, essentially telling consumers that it’s up to them to decide if the product works. Critics of the law describe this disclaimer as the “quack Miranda warning”—a meaningless phrase invoked automatically to mask a range of unsupported medical claims.In a statement, the FDA reiterated to me that “products claiming to cure, treat, mitigate, or prevent diseases are drugs—and are subject to all requirements that apply to drugs—even if they are represented as ‘dietary supplements,’” and added that while it wouldn’t comment on Uqora specifically, the agency is “authorized to take action against violative products.”When I asked Uqora about how it can make claims that are directly contradictory to the FDA disclaimer printed at the bottom of their site, co-founder Spencer Gordon told me that “dietary supplements sit in sort of a gray area between two regulatory bodies, the FDA and the FTC,” with “the FDA regulating product packaging and labeling, specifically, and the FTC regulating actual marketing claims.” This means, he argued, “as far as the FDA, our packaging doesn't say anything about prevent[ing] UTIs because that's not an approved FDA claim for the dietary ingredients inside the formula at this time.” To clarify, I asked if he meant that because packaging itself doesn’t make claims about preventing UTI, it doesn’t matter that all the marketing materials do make that claim; Gordon said that was correct. Presumably, Orrin Hatch would be thrilled to hear that Uqora remains free to make contradictory claims under the law he authored.But Gordon’s understanding doesn’t appear to be true: The FDA has sent many warning letters in the past to dietary supplement companies over online marketing, not just literal product packaging. In July, the FDA sent a warning letter to a company called Curaleaf for claims it made about its CBD products on its website, Facebook, and Twitter about being designed “for chronic pain” and aimed at “reduc[ing] anxiety symptoms.” Many other similar warning letters from the FDA cite website claims. The FTC does regulate marketing claims for supplements too, and neither the FDA nor FTC would comment on Uqora specifically, but even the logic of Gordon’s argument is strained: How would a consumer even see the packaging and labeling of an online product before they purchased it?This isn’t to say that Uqora necessarily does nothing. One 2014 randomized controlled trial published in the World Journal of Urology tested the same dose of d-mannose that Target contains on 308 people, and did find that it “significantly reduced the risk of recurrent UTI.” The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence said in 2018 that this 2014 trial provided “high quality” evidence for d-mannose’s effectiveness, and suggested that non-pregnant people with vaginas with recurrent UTIs “may wish to try D-mannose, as a self-care treatment,” but noted that the trial was “small.” In 2018, the American Urogynecologic Society’s Best Practice Statement for recurrent UTIs said there was “limited” evidence for d-mannose’s effectiveness. The same paper said there is “insufficient” evidence to recommend the use of Vitamin C, another ingredient in Uqora’s Target. As for curcumin, even a post on Uqora’s own site says turmeric is only “rumored” to prevent UTIs, and notes that “whether or not curcumin is effective at killing E. coli in humans is not certain, and requires more research.”Uqora keeps information sheets outlining the scientific basis for its claims that cite studies on the products’ various ingredients, such as one that shows curcumin can break up infection-causing “biofilms.” But there are no studies cited that demonstrate curcumin’s effectiveness in treating UTIs. Chris D’Adamo, the Director of Research at the Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Maryland who has served as principal investigator on many studies of dietary supplements, said the evidence Uqora offered was “pretty typical of the industry,” and that while it was “better than most companies,” Uqora was nonetheless “connecting some dots that aren’t really there.” The studies merely establish the mechanism by which the ingredient might work to prevent UTIs, not that they actually do.David Seres, director of medical nutrition and associate professor of medicine at the Institute of Human Nutrition, Columbia University Medical Center, said that Uqora’s arguments are “not medically credible without direct testing” of the actual product to make a prevention claim. Uqora is conducting a clinical trial of its products, but the results won’t start to become available until 2020; D’Adamo noted that the “study on their finished product would connect the dots and would be commendable.” Until then, the products are still on sale, still making the same claims.Uqora is hardly the worst offender in the dietary supplement industry. The law is set up to make it easy for companies to make claims that skirt the law, if not actively flout it, and the deluge of products making health and wellness claims online has shown that the FDA doesn’t have the capacity to go after most cases. And the industry has worse problems than misleading claims: The FDA’s own data shows that unapproved prescription drugs exist in 20 percent of dietary supplements. But the fact remains that Uqora is making a claim that it shouldn’t be making, and there’s a reason we’re meant to have laws in place to regulate the strongest claims about treating and preventing diseases, which is that we can’t trust companies to be responsible in making claims to sell products. Not even the ones with the best Instagram ads.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement