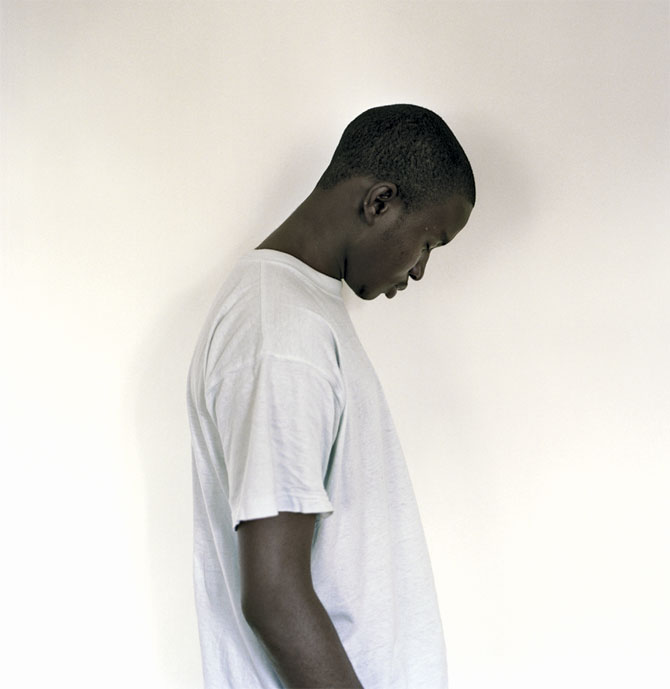

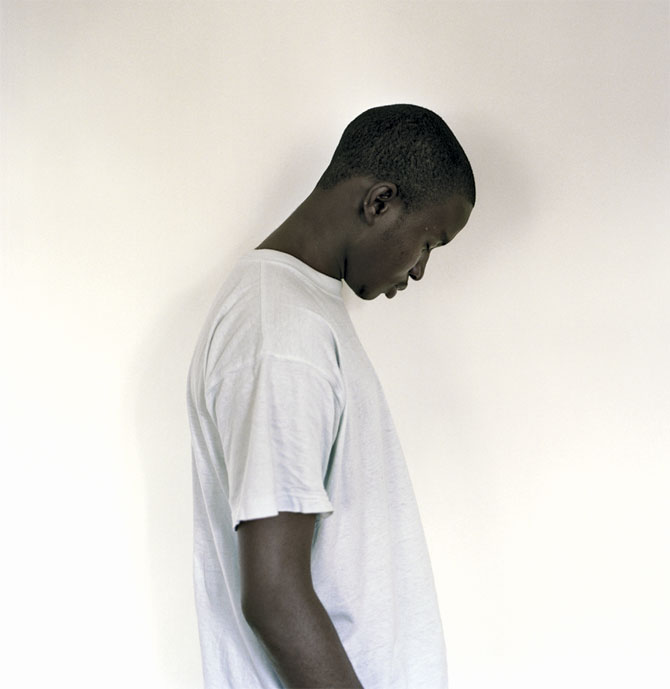

Interviews By Martina KixPhotos By Tanja KernweissRecent reports figure that as many as 250,000 child soldiers are being forced to fight in war zones across the globe at this very moment. According to Terre des Hommes, a group of gigantic-hearted folks that acts on behalf of mistreated kids, each year nearly 500 of these young people escape and seek refuge in Germany. It’s no surprise that German lawmakers and many of the people they represent gripe and bitch about these outsiders persistently, enacting sketchy legislation that classifies them as “deserters” and forbids most from roaming the country freely for fear of deportation. Essentially, many of those granted asylum are held captive in the very centers that have rescued them.Dr. Albert Riedelsheimer has been working with refugees for more than 17 years and is one of the founders of the Separated Children humanitarian organization in Munich. He introduced us to William* and Paul,* two former child soldiers from Sierra Leone, and Mohammad,* a refugee from Afghanistan who narrowly escaped involuntary recruitment into the Taliban. They were kind enough to talk openly about the senseless horrors they have experienced and what an unbelievable pain in the ass it is establishing an identity without a birth certificate in a country that doesn’t want them there in the first place.*Names have been changed and faces have been obscured for obvious reasons. WILLIAM, 16, SIERRA LEONEVice: Hello, William. Thanks for traveling all the way from Böbrach to Munich to chat. I hope it wasn’t a hassle.William:No, thank you for inviting me. I’m glad to come. The German bureaucracy is pretty strict, and every time I want to leave the asylum center I need to get official permission. “To see friends” isn’t a good enough reason for German officials. If I leave the center without permission and the police stop me on the street, they can deport me.The civil war in Sierra Leone has been over since 2002. How did you manage to escape?My family and I used to live in Lungi, which is a small city two hours from Freetown. Around 2000 or 2001 the war suddenly got a lot worse. I was nine years old when my mom decided to take my sisters and me to Guinea because she wanted us to grow up in a safer environment. On our way, the Revolutionary United Front [RUF] captured us and took us to one of their camps. We couldn’t do anything because they numbered in the hundreds and had weapons.What happened at the camp?First they killed my two sisters. Before that they probably raped them. They told me that if I didn’t work as a spy, they would kill my mom. I really had no choice. They told me I should go to the other village, beg for food, and hang out with the opposing soldiers. Every evening I had to travel back to the RUF camp and report what I heard. I was lucky to work as just a spy. I heard stories of other kids who were in charge of cutting off the hands and arms of captive men. The rebels wanted to make sure that they wouldn’t fight again. The only option they had was “Short sleeve or long sleeve?” I still have nightmares about it.How close did you come to being killed?After working as a spy for a couple of months the soldiers I was spying on started to ask questions about me and other children: “Where are those kids from? What do they do? Why are they just here from morning till evening?” I was spying with two other kids, and they started to recognize us. They took us to the captain and he beat us up. In the end we lied and they believed that we weren’t spies. They would have killed us right away if they knew the truth. Then when we got back to the RUF camp they beat us up because they thought we had changed sides.Were you ever forced into combat?There’s this phrase in Sierra Leone: “The blood is behind me!” It means that the blood of the victims will chase you till the end of your days. I don’t want to talk about it.What haunts you the most about your time with the RUF?I don’t know… a lot of bad things happened. One day the RUF soldiers went to a village and raped the women there. They made me watch. When they saw a pregnant woman they would bet on whether it was a boy or girl. Afterward they would cut the woman’s belly open to find out. One time the soldiers forced me to join in.My God. And somehow you managed to escape. Can you tell us about that?I met a man who decided to help me. He told me that I should go on one of those container ships bound for Europe. I didn’t really know my final destination. It didn’t matter. I just wanted to leave and find a better life. I was a blind passenger. I can’t really tell you how long the journey was because I totally lost track of time. Maybe a month or longer? I was hiding the whole time in one of the containers. I didn’t see a lot of light. I packed some food, but I barely had anything to drink.What were your first impressions of Germany?There were so many people on the streets running around. I was lost because I didn’t find the right people to help me or tell me what to do and where to go. From Bremen they sent me to Munich. After three months in Munich they sent me to Böbrach. That’s what they do with refugees. Nobody stays in the big cities where they first arrive. The German asylum law is complicated and I don’t really understand it. They just send the people from place to place. It’s pretty bad.What’s it like where you’re living now?In my room there are seven men, but in other rooms there are more people. The place is very small. We have bunk beds and a little kitchen, but the kitchen has no window. We don’t have sheets for our beds, just some blankets. In the winter it gets really cold and a lot of people get sick.Do you feel welcome here?It’s very difficult for me. When I arrived the officers didn’t want to believe me—that I’m underage—because I didn’t have a birth certificate. Nobody in Sierra Leone has a birth certificate. I was born when the war was already going on. There were far more important things than birth certificates. Anyway, because of this, I had to go through a grown-up refugee application instead of an underage one. That’s why I got sent to Böbrach instead of an asylum center for young refugees. My guardian is putting together a claim so that when they finally believe that I’m underage I can go back to Munich where my friends are.What are your plans for the future?I used to write songs during my free time and thought that I could get into music. I like Jay-Z and Sean Paul a lot. I would like to enroll in a business class. I would like to get a diploma or something, but I’m afraid that this won’t happen here.

WILLIAM, 16, SIERRA LEONEVice: Hello, William. Thanks for traveling all the way from Böbrach to Munich to chat. I hope it wasn’t a hassle.William:No, thank you for inviting me. I’m glad to come. The German bureaucracy is pretty strict, and every time I want to leave the asylum center I need to get official permission. “To see friends” isn’t a good enough reason for German officials. If I leave the center without permission and the police stop me on the street, they can deport me.The civil war in Sierra Leone has been over since 2002. How did you manage to escape?My family and I used to live in Lungi, which is a small city two hours from Freetown. Around 2000 or 2001 the war suddenly got a lot worse. I was nine years old when my mom decided to take my sisters and me to Guinea because she wanted us to grow up in a safer environment. On our way, the Revolutionary United Front [RUF] captured us and took us to one of their camps. We couldn’t do anything because they numbered in the hundreds and had weapons.What happened at the camp?First they killed my two sisters. Before that they probably raped them. They told me that if I didn’t work as a spy, they would kill my mom. I really had no choice. They told me I should go to the other village, beg for food, and hang out with the opposing soldiers. Every evening I had to travel back to the RUF camp and report what I heard. I was lucky to work as just a spy. I heard stories of other kids who were in charge of cutting off the hands and arms of captive men. The rebels wanted to make sure that they wouldn’t fight again. The only option they had was “Short sleeve or long sleeve?” I still have nightmares about it.How close did you come to being killed?After working as a spy for a couple of months the soldiers I was spying on started to ask questions about me and other children: “Where are those kids from? What do they do? Why are they just here from morning till evening?” I was spying with two other kids, and they started to recognize us. They took us to the captain and he beat us up. In the end we lied and they believed that we weren’t spies. They would have killed us right away if they knew the truth. Then when we got back to the RUF camp they beat us up because they thought we had changed sides.Were you ever forced into combat?There’s this phrase in Sierra Leone: “The blood is behind me!” It means that the blood of the victims will chase you till the end of your days. I don’t want to talk about it.What haunts you the most about your time with the RUF?I don’t know… a lot of bad things happened. One day the RUF soldiers went to a village and raped the women there. They made me watch. When they saw a pregnant woman they would bet on whether it was a boy or girl. Afterward they would cut the woman’s belly open to find out. One time the soldiers forced me to join in.My God. And somehow you managed to escape. Can you tell us about that?I met a man who decided to help me. He told me that I should go on one of those container ships bound for Europe. I didn’t really know my final destination. It didn’t matter. I just wanted to leave and find a better life. I was a blind passenger. I can’t really tell you how long the journey was because I totally lost track of time. Maybe a month or longer? I was hiding the whole time in one of the containers. I didn’t see a lot of light. I packed some food, but I barely had anything to drink.What were your first impressions of Germany?There were so many people on the streets running around. I was lost because I didn’t find the right people to help me or tell me what to do and where to go. From Bremen they sent me to Munich. After three months in Munich they sent me to Böbrach. That’s what they do with refugees. Nobody stays in the big cities where they first arrive. The German asylum law is complicated and I don’t really understand it. They just send the people from place to place. It’s pretty bad.What’s it like where you’re living now?In my room there are seven men, but in other rooms there are more people. The place is very small. We have bunk beds and a little kitchen, but the kitchen has no window. We don’t have sheets for our beds, just some blankets. In the winter it gets really cold and a lot of people get sick.Do you feel welcome here?It’s very difficult for me. When I arrived the officers didn’t want to believe me—that I’m underage—because I didn’t have a birth certificate. Nobody in Sierra Leone has a birth certificate. I was born when the war was already going on. There were far more important things than birth certificates. Anyway, because of this, I had to go through a grown-up refugee application instead of an underage one. That’s why I got sent to Böbrach instead of an asylum center for young refugees. My guardian is putting together a claim so that when they finally believe that I’m underage I can go back to Munich where my friends are.What are your plans for the future?I used to write songs during my free time and thought that I could get into music. I like Jay-Z and Sean Paul a lot. I would like to enroll in a business class. I would like to get a diploma or something, but I’m afraid that this won’t happen here. MOHAMMAD, 16, AFGHANISTANVice: Hey, Mohammad. So you want to do this interview in German? It’s pretty impressive that you know the language already.Mohammad:Thanks. I try to get better every day. We have a good teacher here and a nice school.What led to your departure from Afghanistan?My father told me that I had to leave Afghanistan or the Taliban would take me away. They force the young boys into military service in the mountains of northern Afghanistan. They train them for a couple of weeks in how to use weapons and how to become martyrs.Tell us about how you escaped.A couple of days before I left Afghanistan they took away some of my friends. My dad watched it happen. I’m sure their families will never see them again because the kids are forced to fight on the front lines. The Taliban likes to use them as protective shields. When the Taliban came I was hiding in an oven that my mom used to make bread. They tried to find me several times over a couple months, but I was always hiding. I don’t know where the Taliban got the information that there was a boy in our house who they could recruit for their war.Did the Taliban kill a lot of people in your village?Yes. The Taliban terrorized us but they didn’t live in my hometown, which is a couple of hours from Kabul. They just came to take away the people to serve as troops and stuff the needed—all the money and the boys.When did you arrive in Germany?About one year ago. It was a long journey. From Afghanistan to Pakistan I traveled by car. From Pakistan to Iran we walked most of the time or rode bicycles, donkeys, and horses. Then we took a truck and a ship. It was horrible. I don’t remember all of it.How was your journey?It was very dangerous, especially between Pakistan and Iran, because if they found me I would’ve been killed on the spot. The whole journey was really exhausting because we had to rush all the time. We didn’t have a lot to drink and almost no food, and wild animals were everywhere. I had a lot of fears.Did you have to pay the people who helped you make it through?My dad paid them, but I don’t know how much. They were professional smugglers.Why Germany?I wanted to go to Germany because it was rebuilt after World War II. The people here know how to rebuild a country. Germany is way better then other countries in Europe. In Germany you find a lot of big factories: Mercedes-Benz, BMW, and Audi. When I can speak the language better and begin school I want to start a career here and help my family in Afghanistan.I’m sure there are plenty of differences between here and Afghanistan.In the beginning I was pretty surprised that there was no chaos on the streets. Everything is very organized. You don’t see soldiers, violence, or crime.Have you had any issues with Germany’s infamous asylum laws?I didn’t have a passport so they didn’t want to believe that I was underage. I’m tall and look older than I am. They asked for a birth certificate and wanted to know how I made my way to Germany. They didn’t want to believe me when I said that I made it on my own. Luckily I met Dr. Riedelsheimer. He helped me get through the whole process and that’s why I’m in this place right now.Your apartment is pretty nice, but do you ever miss home?I miss my family. They think that everything is going to be better here for me. My father has a very strong belief in God, and he will never, ever leave my home village. I hope I can send them money when I get a good job.What do you do in your free time?I love tae kwon do. I want to be really good at it!

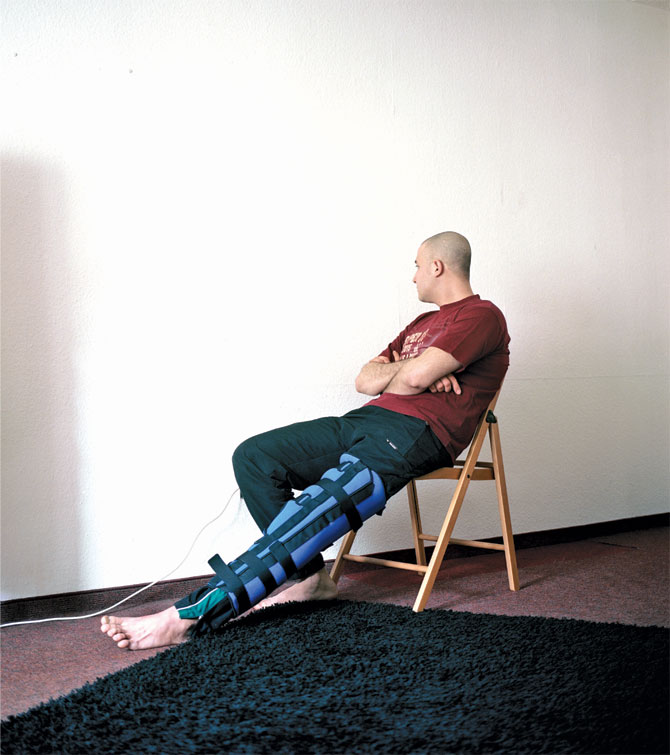

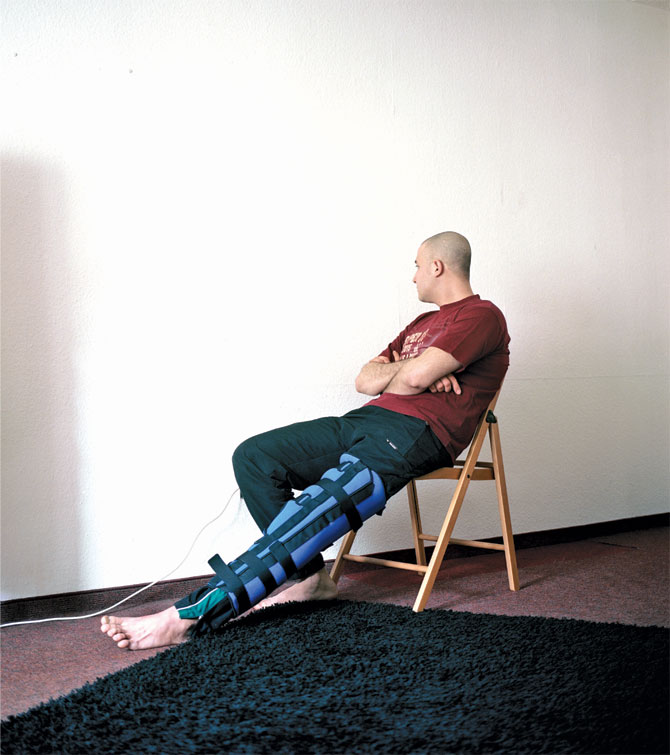

MOHAMMAD, 16, AFGHANISTANVice: Hey, Mohammad. So you want to do this interview in German? It’s pretty impressive that you know the language already.Mohammad:Thanks. I try to get better every day. We have a good teacher here and a nice school.What led to your departure from Afghanistan?My father told me that I had to leave Afghanistan or the Taliban would take me away. They force the young boys into military service in the mountains of northern Afghanistan. They train them for a couple of weeks in how to use weapons and how to become martyrs.Tell us about how you escaped.A couple of days before I left Afghanistan they took away some of my friends. My dad watched it happen. I’m sure their families will never see them again because the kids are forced to fight on the front lines. The Taliban likes to use them as protective shields. When the Taliban came I was hiding in an oven that my mom used to make bread. They tried to find me several times over a couple months, but I was always hiding. I don’t know where the Taliban got the information that there was a boy in our house who they could recruit for their war.Did the Taliban kill a lot of people in your village?Yes. The Taliban terrorized us but they didn’t live in my hometown, which is a couple of hours from Kabul. They just came to take away the people to serve as troops and stuff the needed—all the money and the boys.When did you arrive in Germany?About one year ago. It was a long journey. From Afghanistan to Pakistan I traveled by car. From Pakistan to Iran we walked most of the time or rode bicycles, donkeys, and horses. Then we took a truck and a ship. It was horrible. I don’t remember all of it.How was your journey?It was very dangerous, especially between Pakistan and Iran, because if they found me I would’ve been killed on the spot. The whole journey was really exhausting because we had to rush all the time. We didn’t have a lot to drink and almost no food, and wild animals were everywhere. I had a lot of fears.Did you have to pay the people who helped you make it through?My dad paid them, but I don’t know how much. They were professional smugglers.Why Germany?I wanted to go to Germany because it was rebuilt after World War II. The people here know how to rebuild a country. Germany is way better then other countries in Europe. In Germany you find a lot of big factories: Mercedes-Benz, BMW, and Audi. When I can speak the language better and begin school I want to start a career here and help my family in Afghanistan.I’m sure there are plenty of differences between here and Afghanistan.In the beginning I was pretty surprised that there was no chaos on the streets. Everything is very organized. You don’t see soldiers, violence, or crime.Have you had any issues with Germany’s infamous asylum laws?I didn’t have a passport so they didn’t want to believe that I was underage. I’m tall and look older than I am. They asked for a birth certificate and wanted to know how I made my way to Germany. They didn’t want to believe me when I said that I made it on my own. Luckily I met Dr. Riedelsheimer. He helped me get through the whole process and that’s why I’m in this place right now.Your apartment is pretty nice, but do you ever miss home?I miss my family. They think that everything is going to be better here for me. My father has a very strong belief in God, and he will never, ever leave my home village. I hope I can send them money when I get a good job.What do you do in your free time?I love tae kwon do. I want to be really good at it! PAUL, 22, SIERRA LEONEVice: Is it OK to ask about your voyage to Germany and how your new life compares to your time as a soldier?Paul:We can talk about everything, but I’m at a point where I want to forget my time as a child soldier. I did therapy and I need to carry on now. You can ask your questions, but I might not answer all of them.Fair enough. How did you begin fighting for the RUF?When I was eight years old they came to our village and burned our houses down. They killed my parents and took me with them. I was way too afraid to make a move or do something drastic—they just forced me to go with them. They took other kids and older men to their camp in the bushes too. It is hard to say how many there were. Like I said, I want to forget about this.I understand. Please ignore any questions you don’t want to answer. What happened when you got to the camp? Did they train you?You don’t really need training. I grew up with weapons, and when the RUF took me I knew what was going on. It was nothing totally surprising. We kids were always running out of our village when the RUF came, but that day it was different.I’ve heard stories that RUF leaders ply kids with drugs and alcohol to get them to join. Is this true?Yes. The leaders took the drugs too. Some of the kids took a lot of drugs. They danced at the camp and got crazy. I always tried to stay out of all of that, but I had no choice. When they gave me certain pills I had to accept them.What happened to the kids who didn’t obey?They got killed right away. Some of the kids tried to leave the camp, but they also got shot.Did you have any specific duties during your time as a soldier?We were fighting in the bushes and robbing villages. It was what we called the “Operation: Yourself” principle, which means we took everything we wanted or needed from people’s houses. Most of the time it was man-to-man fighting. There were land mines and bombs too, but not that many. The weapons came from Liberia and it was all about diamonds and power. The whole civil war was about that.How did you manage to escape?I didn’t really expect it. I was 14 years old at that time. We were in a big fight in the bush where a lot of people got killed. Afterward I just ran away across the border to Guinea. I changed my clothes, threw away all of my stuff, and hid in an old woman’s house for a couple of days.Wasn’t there also fighting in Guinea around that time? Were other soldiers looking for you?There were fights at the border, and if they had found me, they would have killed me. The woman I stayed with put me in contact with a smuggler. He got me on a truck that took me through Guinea. At the coast I got on a ship as a blind passenger and it took me to Germany.How much did you have to pay the smugglers?$1,500.Wow, how did such a young boy get that kind of money?I’m not telling you.OK. Did they even tell you where the ship was going?No. I was hiding the whole time and I was not allowed to walk around.Did you see any other kids?I’m sure there were more of us on the boat. The guy who smuggled me gave me some food. I had no idea where the ship would go. I think I arrived in Hamburg. I still can’t tell for sure. When I arrived I took a train and went to a different city, and then when I came to the first asylum camp I found out that I was in Germany.Were there any problems with your asylum application?Yes. It was pretty hard. I was able to read a little because my dad showed me. He was a teacher. I didn’t sign anything until I met Dr. Riedelsheimer. The asylum officers were fighting for a couple of days and then they decided that I was underage. I had to leave the first center and was sent to Munich.Are you working now?I work as a translator here in the center and in a big supermarket in the fruits-and-vegetables section. When someone wants to know where some kind of fruit is from or how it tastes, I help them. It’s a nice job and I like it. I like to live here and can’t imagine going back. We have a little apartment in the suburbs of Munich. We don’t have a lot of money, but we can make a living.You say “we.” Do you have a girlfriend?Yeah. We’ve been together for four years now. I’m happy with her. She is from Guinea and works as a cleaning lady. She also takes care of our kids. We have three boys.Is there still a place in your heart for Sierra Leone? Do you miss it sometimes?Yeah, from time to time. I miss the good weather and the food, but there are way too many bad memories connected to that place. I don’t see any reason why I should go back. I mean, what am I supposed to do there? I went back to Guinea last year for the first time. We visited the hometown of my girlfriend. It was pretty similar.Have you told your children about your past?When I’m with my family I don’t think about the war. Not even my girlfriend knows what I did. I’m a normal dad and I like to play with my kids. I don’t want my kids to know. I don’t want them to play war games. They really don’t need plastic weapons.

PAUL, 22, SIERRA LEONEVice: Is it OK to ask about your voyage to Germany and how your new life compares to your time as a soldier?Paul:We can talk about everything, but I’m at a point where I want to forget my time as a child soldier. I did therapy and I need to carry on now. You can ask your questions, but I might not answer all of them.Fair enough. How did you begin fighting for the RUF?When I was eight years old they came to our village and burned our houses down. They killed my parents and took me with them. I was way too afraid to make a move or do something drastic—they just forced me to go with them. They took other kids and older men to their camp in the bushes too. It is hard to say how many there were. Like I said, I want to forget about this.I understand. Please ignore any questions you don’t want to answer. What happened when you got to the camp? Did they train you?You don’t really need training. I grew up with weapons, and when the RUF took me I knew what was going on. It was nothing totally surprising. We kids were always running out of our village when the RUF came, but that day it was different.I’ve heard stories that RUF leaders ply kids with drugs and alcohol to get them to join. Is this true?Yes. The leaders took the drugs too. Some of the kids took a lot of drugs. They danced at the camp and got crazy. I always tried to stay out of all of that, but I had no choice. When they gave me certain pills I had to accept them.What happened to the kids who didn’t obey?They got killed right away. Some of the kids tried to leave the camp, but they also got shot.Did you have any specific duties during your time as a soldier?We were fighting in the bushes and robbing villages. It was what we called the “Operation: Yourself” principle, which means we took everything we wanted or needed from people’s houses. Most of the time it was man-to-man fighting. There were land mines and bombs too, but not that many. The weapons came from Liberia and it was all about diamonds and power. The whole civil war was about that.How did you manage to escape?I didn’t really expect it. I was 14 years old at that time. We were in a big fight in the bush where a lot of people got killed. Afterward I just ran away across the border to Guinea. I changed my clothes, threw away all of my stuff, and hid in an old woman’s house for a couple of days.Wasn’t there also fighting in Guinea around that time? Were other soldiers looking for you?There were fights at the border, and if they had found me, they would have killed me. The woman I stayed with put me in contact with a smuggler. He got me on a truck that took me through Guinea. At the coast I got on a ship as a blind passenger and it took me to Germany.How much did you have to pay the smugglers?$1,500.Wow, how did such a young boy get that kind of money?I’m not telling you.OK. Did they even tell you where the ship was going?No. I was hiding the whole time and I was not allowed to walk around.Did you see any other kids?I’m sure there were more of us on the boat. The guy who smuggled me gave me some food. I had no idea where the ship would go. I think I arrived in Hamburg. I still can’t tell for sure. When I arrived I took a train and went to a different city, and then when I came to the first asylum camp I found out that I was in Germany.Were there any problems with your asylum application?Yes. It was pretty hard. I was able to read a little because my dad showed me. He was a teacher. I didn’t sign anything until I met Dr. Riedelsheimer. The asylum officers were fighting for a couple of days and then they decided that I was underage. I had to leave the first center and was sent to Munich.Are you working now?I work as a translator here in the center and in a big supermarket in the fruits-and-vegetables section. When someone wants to know where some kind of fruit is from or how it tastes, I help them. It’s a nice job and I like it. I like to live here and can’t imagine going back. We have a little apartment in the suburbs of Munich. We don’t have a lot of money, but we can make a living.You say “we.” Do you have a girlfriend?Yeah. We’ve been together for four years now. I’m happy with her. She is from Guinea and works as a cleaning lady. She also takes care of our kids. We have three boys.Is there still a place in your heart for Sierra Leone? Do you miss it sometimes?Yeah, from time to time. I miss the good weather and the food, but there are way too many bad memories connected to that place. I don’t see any reason why I should go back. I mean, what am I supposed to do there? I went back to Guinea last year for the first time. We visited the hometown of my girlfriend. It was pretty similar.Have you told your children about your past?When I’m with my family I don’t think about the war. Not even my girlfriend knows what I did. I’m a normal dad and I like to play with my kids. I don’t want my kids to know. I don’t want them to play war games. They really don’t need plastic weapons.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement