I was minding my own business when she headbutted me. It was a small show—Adia Victoria's first in the UK—in an intimate basement bar with a cap of 80. Adia, 6ft in heels, confrontational with an accusatory glare, singing wild blues. During one song she walked over, stole a guy's whisky, strolled back to the makeshift stage and downed it. Then during a chilling cover of Robert Johnson's "Me And The Devil Blues" she grabbed me, smashed her head into mine and held it there, pressing my skull to hers while she howled: "Baby you know you ain't doin' me right." She seemed possessed. Then she discarded me and carried on singing about being buried by the highway.

Advertisement

The next day we meet for lunch in a pub in Kensington, a snazzy, silly part of London where her label is based. I tell her it was me she'd headbutted. "I don't even remember doing that," she says. And I thought I was special.Originally from Spartanburg County, South Carolina, these days the singer lives in Nashville. Released a few months back, her debut LP Beyond the Bloodhounds, was a lifetime in the making. It's an animal of an album, marking its territory with merciless attacks, and getting uncomfortably close in its confessionals. Her voice is as fragile as it is strong, her guitar creepy and defiant. She draws you in and schools you. Even the raucous, sweatier cuts don't disguise the damage and vulnerability."Sorry, I'm long-legged," she says, stretching out in the pub after ordering a plate of pork belly. She's friendlier today, offstage. We talk about the show, the drama intrinsic in her performance, how she commanded the crowd. "It helps that I had to go through my 20s and try on all these different identities, because it's just been very recently that I've found self-esteem and confidence," she says. "Before I wasn't sure who I really was. As much as I love pop stars, I never saw myself validated in them, it was always something that I had to aspire to be: That level of cool, or that beautiful. Now I'm 30 I have a much better idea of what makes me happy, what speaks to me, and what I want to share with people via my art. So it feels like the most natural thing in the world to go onstage and do what I did last night."

Advertisement

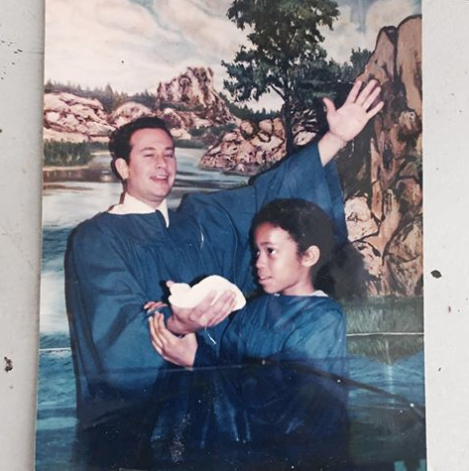

Sharing her music with people in little venues, she says, validated the experiences that went into writing the songs. It's all very therapeutic, she explains."It's made me question the way I thought certain things happen, the way I thought I was. Everything seemed so black and white to me before, growing up. And I had a lot of unpacking to do."///Spartanburg County is a prosperous, middle-class town that in the late 19th century saw its fair share of Klan activity and lynchings. Adia grew up there in the 80s, when crack was ripping through the black population, and despite a contemporary veil of progression, she suffered daily, institutionalized racism. As she saw it, to be successful was to be white, and she was ashamed of being black. Her Trinidadian father served in the military and was often overseas, so alongside her siblings, she was mostly raised by her mother as a Seventh-day Adventist. Adia attended a white church school, and found spiritual joy singing in the choir. Otherwise however, religion crushed her. Onstage she spoke of how the church had fucked her up, before singing about it: "Invisible hands wrapped around my throat / Won't let me be / Won't let me go.'"Church raptured me from my own human experience," she tells me with a tone that suggests she's out for blood. "It made my own body off limits to me, my own experiences off limits to me—they were forbidden, they were taboo. And they arrayed the world into right, wrong, black, white, and the only thing I was here to do was to get to Heaven. It was never about being in the moment, it was never about understanding my humanity. It was always about being good enough to get the reward when I die. So as a child, it terrified me to the core. I was afraid to do anything because I was like, 'Someone's sitting in the sky taking tallies of what I'm doing? Wait, what? And if I make a mistake, if I tell a fib, I'm gonna burn in hell? So psychologically as a kid, I couldn't believe the way that they wanted me to believe, because it would have torn me apart."

Advertisement

It was hard for young Adia to envisage a world beyond South Carolina: All of the media she consumed was approved by the church; she'd been battered into submission by cultural messages. "I felt like, 'What's the point of even being alive? What does the world have waiting for me, what's my social inheritance?' And there was none." College, work, marriage, popularity meant nothing, because she hadn't been conditioned to expect a healthy future. In sixth grade, her mother took her out of the church and, at 11-years-old, Adia was sent to a multicultural public school. Still, this switch up brought no relief—she felt isolated, like she didn't belong, a feeling that would stay with her for years. The way she describes it sounds like Stockholm syndrome. "The church school was my whole world," she explains. "All my friends and peers were in that small community. If you put a rat in a wheel, in a cage, and then remove the walls, it's not gonna go further than that, because that's all it knows. So going out into public school for the first time when I was 11, I was terrified. It was like I was living a different life. Because everything that I knew was gone."

She found relief in nature, retreating to her grandmother's house, reveling in her relative insignificance in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains. She became a voracious reader, and in her teens began to discover music on her own terms—Lauryn Hill, riot grrrl, Nirvana, and notably Fiona Apple, whose unfiltered honesty gave Adia the confidence to be herself, to stop pandering to other's expectations. But these were baby steps. She still felt trapped and stifled in South Carolina, later writing about it in "Stuck In The South": "I been twitchin' cold in the summer heat / Sayin' please get me out / Or God put me down." At 18, with a lot of gumption and some saved funds, she split.

Advertisement

It was the tail end of 2004 and Bush had just been re-elected when Adia wanted to flee not just the south, but America. She went to London and Paris for some soul-searching then came back, ending up in Brooklyn for a couple of years, people-watching, living as "a ghost" in Prospect Heights, making ends meet working at Abercrombie & Fitch. In 2007, at 21, she moved to Atlanta, where a friend gave her an acoustic Washburn guitar and she started writing songs. She got a telemarketing job and learned chords via YouTube. She rescued Mortimer, a fat black cat with missing teeth who was about to be put down, and sang her songs to him. She fell for The White Stripes and The Black Keys, which lead her to Robert Johnson, RL Burnside, Skip James, and Victoria Spivey. These artists were a revelation: the socio-political world of the blues gave her roots, instilled her with black pride, opened her to a history she never knew she had. Instead of shame, she felt allegiance.During this period Adia went through what she calls her wild years, a self-destructive tear. At her live show I noticed 'God bless the child' inked between her shoulders, so I ask her about Billie Holiday. "I got that tattoo in 2009 when I was living in Atlanta," she says. "I was living like there was no tomorrow. And even in the height of my psychosis, my mania, I knew I had a purpose. I didn't know what, and maybe it was angels watching out after me when I should have been killed, or dropped dead. But Billie Holiday, she lived hard, she was wild. She lived dangerously. And it's like, 'God, you better look out after me, because I'm doing the most to kill me.'"

Advertisement

I press her to elaborate. "There was a time in my life when I wanted to die. I tried to die," she says. "It's so difficult to speak about because there's really not a mainstream outlet for black women with mental illness issues. Depression, suicide attempts, that's not really something that we talk about—we're always told, 'Be strong, carry on. Pray about it, pray about it to God.' But what happens when I don't believe in God and I'm stuck here inside of myself and I don't know if I want to continue living the way I'm told to live? That all came to a head in my early 20s. And after that was the poetic ways of being self-destructive, the drinking too much, the self-sabotage, quitting jobs, getting fired, smoking, and doing coke. Those were the years in Atlanta, fucking like, whatever. Don't care."

"Her song "Dead Eyes" is a tribute to that period: 'You don't believe in God, hey, whisky will do.' She spent three years in Atlanta before moving to Nashville to join her mother, who had relocated there. Adia enrolled in college to study French, and, having moved from acoustic to electric, started performing small shows. In 2012, reflecting on her hedonism, she started writing the songs that would make up Beyond the Bloodhounds. One of the first, "Mortimer's Blues," which sounds like vintage Breeders, she wrote after her cat died. Then in July 2014, having formed her band and found a producer, she posted "Stuck in the South" online and began playing shows in earnest. With the Black Lives Matter movement gathering momentum, she wanted to make her songs, and her life, public. In the two days preceding her London show this July, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile were killed. She dedicates the stark, wrathful "Howlin' Shame" to Sterling. Her words shook the walls: "A murder of crows / They followed her home / And they didn't leave much / Just a bed of bones."

Advertisement

When we meet the next day, police are being killed by snipers in Dallas. I ask what it's like to be here singing these songs in London with all the violence happening back home. "I wouldn't know what else to do but sing about that," she says. "Being black in America—you're in a state of constant trauma—because you understand that that can happen to you and there's nothing you can do to stop it. You can never be respectable enough, you can never be good enough, or non-threatening enough, because people in America have been brainwashed and socialized and conditioned to see you as a threat. Just because of the color of my skin, I'm a threat to you. We're not dealing with logic here, we're not dealing with reason, we're dealing with insanity. I have two big brothers and I fear for them. I fear that one day a police officer will pull them over and ask them for their wallet and registration and freak out and shoot them."My brothers are two amazing men, but that's not even the point: they could be thugs, and that doesn't give an officer the right to execute you in the street. To lynch you. But the way that my country works, it does. And that's why they're constantly excused of this. The state gives them their permission to execute black people. That's part of our legacy—as much as apple pie on the 4th of July, it's also destroying black bodies. That's part and parcel of America."Reading the news that week made her anxious, angry. She vented on stage. "I've always dedicated "Howlin' Shame" to black victims of state-sanctioned violence," she says. "Because I think it's important to say their name and bear witness to them, and keep them alive. And to let people know that I haven't forgotten, and as long as you interact with me and my art, then neither will you. I won't let you. Being a black girl from the deep South, this is my story, and if I'm not up there telling the truth, then it's time for me to excuse myself and get off the stage."

Advertisement

She wrote "Howlin' Shame' about growing up in Spartanburg, acutely aware, as a child, that she had no standing in the world. In many ways, she says, little has changed in the south. A year ago on Facebook, she wrote about walking home from work and having white men sexually proposition her on the street; as she wrote the post, she could hear "an old white man on the phone laughing about the black pussy downstairs he used to fuck." "I think that we put a nice veneer on top of a rotted tooth of racism," she says now. "Martin Luther King had a dream, and the kids can go to school together, even though the schools are re-segregated again, due to redlining and redrawing districts and gerrymandering—segregation is as real now as it was in 1950. And the onus of racism has always been on black people, for us to uplift our race: 'Rise up, black man.' No, we're fine—white people invented this shit. Y'all the ones who have problems. This whole mentality came from y'all's minds. That's sick. That's really fucking sick!"Her knowledge, fury, and eloquence make for a heavy, thrilling, and sometimes intimidating interview. As a sheltered middle-class white boy, I ask questions then just shut up. Everything she says, she delivers with quiet force and utter confidence, and I'm left feeling a little battered, but enriched. She recommends the work of Ta-Nehisi Coates who, in his book Between The World And Me, wrote that racist whites say that racism is just God's way. Even as a child, Adia says, she didn't believe in the version of God that she was supplied with, a white Jesus in the sky. Her god, she says, keeps her in touch with her humanity, reminds her to not present herself a brand. "Because we're not always gonna be flawless, we're not always gonna be picture-perfect and Instagram-ready," she states. "Human beings are messy. I'm messy. I know what you're going through. I think people are grateful that they can see that, that someone is showing what the hurt feels like, what the anxiety looks like. Because everyone's going through it. I know you are. I don't care what you put online on social media, what you try and appear to be—I know that's bullshit."She's steadfast in her own resistance of image, labelling, categorization. Nashville in particular, she says, is a town where everyone brands themselves, desperate to be recognized. She has disdain for its cheesiness. Certain quarters have seized on her mentions in the media of Johnny Cash and Hank Williams (who she got into around the same time she discovered the blues), and want to claim her as country. She hates this because she thinks girls of color won't find her if she's filed under that banner. "That's where I am right now!" she says as we wrap up. "I'm fighting against that machine. Against people that want to claim me and say, 'You're country, you're Americana!' And I'm like, 'No, I'm not. I'm not yours. I'll never be yours."

Adia Victoria US Tour Dates

9/20 - Chicago, IL - Schubas (XRT's First Impressions Concert Series)

9/21 - Appleton, WI - Mile of Music Concert Series

9/22 - Green Bay, WI - Backstage at the Meyer Theater

9/23 - Iowa City, IA @ The Mill

9/24 - Columbia, MO - Cafe Berlin

9/25 - St Louis, MO - Off Broadway

10/16 - Washington, D.C. - DC9

10/17 - Philadelphia, PA - Johnny Brenda's

10/18 - Brooklyn, NY - Baby's All Right

10/19 - Boston, MA - Great ScottEuropean Tour Dates

10/24 - London, UK - The Hoxton Square Bar and Kitchen

10/26 - Café de la Dance, Paris, France

10/28 - Paradiso – London Calling, Amsterdam, Netherlands

10/29 - AB Club, Brussels, Belgium

10/31 - Private Club, Berlin, Germany

11/02 - Cologne, Germany - Blue Shell

11/03 - Hamburg, Germany – Hafenklang

11/05 - Icelandic Airwaves, Reykjavik - IcelandAlex Godfrey is a writer living in London. Follow him on Twitter. Beyond the Bloodhounds is out now via Atlantic

9/20 - Chicago, IL - Schubas (XRT's First Impressions Concert Series)

9/21 - Appleton, WI - Mile of Music Concert Series

9/22 - Green Bay, WI - Backstage at the Meyer Theater

9/23 - Iowa City, IA @ The Mill

9/24 - Columbia, MO - Cafe Berlin

9/25 - St Louis, MO - Off Broadway

10/16 - Washington, D.C. - DC9

10/17 - Philadelphia, PA - Johnny Brenda's

10/18 - Brooklyn, NY - Baby's All Right

10/19 - Boston, MA - Great ScottEuropean Tour Dates

10/24 - London, UK - The Hoxton Square Bar and Kitchen

10/26 - Café de la Dance, Paris, France

10/28 - Paradiso – London Calling, Amsterdam, Netherlands

10/29 - AB Club, Brussels, Belgium

10/31 - Private Club, Berlin, Germany

11/02 - Cologne, Germany - Blue Shell

11/03 - Hamburg, Germany – Hafenklang

11/05 - Icelandic Airwaves, Reykjavik - IcelandAlex Godfrey is a writer living in London. Follow him on Twitter. Beyond the Bloodhounds is out now via Atlantic