Thomas Ruff: I have to admit that I don’t care much about the texts. I read them once and that’s about it. I spend enough time doing my work. I don’t feel like providing theories or trying to put them into perspective. I know what I do and I can explain it. But I don’t have a superstructural theory or ideology that is above all my work. I think many people are drawn to your portraits. Any idea why?

It might be because there is nothing more interesting or beautiful than a face or a portrait. As a student I only did small formats because I had no money for big prints, and everybody patted me on the back, saying, “Great, Thomas, nice photos. Keep it up!” Still, nobody bought them. I didn’t earn money. Did you consider giving the large-scale fine-art work up for something more commercial?

I thought I would have to do commissioned work for the rest of my life and do art photography alongside. Then with the art portraits, everything turned around. This was the emancipation of contemporary photography in the art scene or on the art market. Buyers and gallery-goers starting coming around.

Suddenly that stuff was in galleries or art fairs and people saw it and couldn’t believe it, that a picture of that size was possible. People who didn’t give a fuck about photography looked at a photo and liked it. Why is that, do you think?

The big format simply has this physical presence—you just couldn’t ignore it. It didn’t matter anymore whether it was silk-screened or photographed. Who are the people in the pictures?

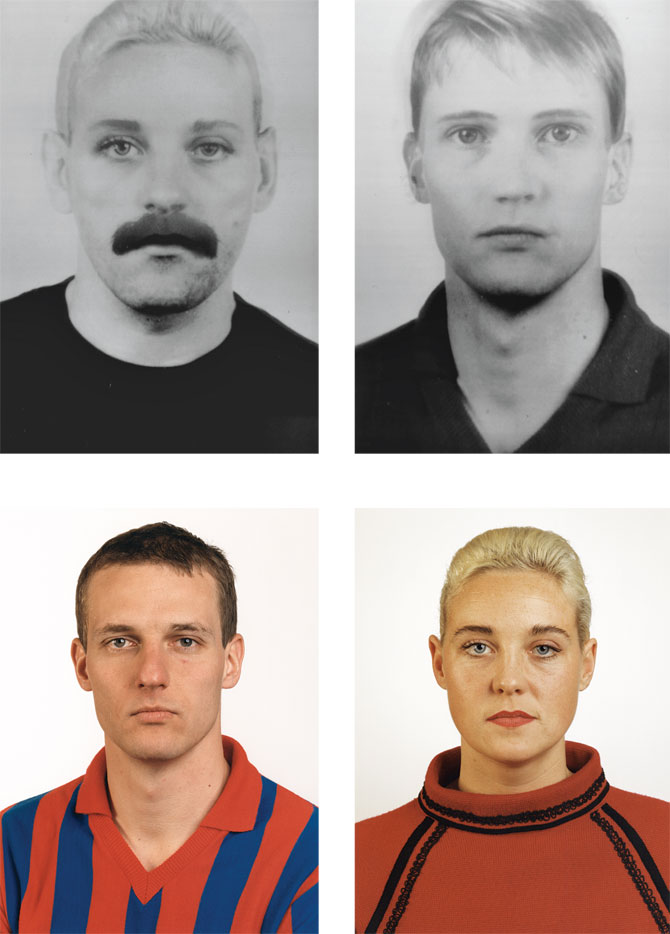

These were all my friends and colleagues from the art academy in Düsseldorf. Once a year they have this walkabout, somewhat of an open-house week. The classrooms are cleaned up and the stuff you did last year is hung on the wall. In 1981 I put my first portraits up—since then whenever I asked somebody if they would sit for a portrait, they said yes. Ninety percent are colleagues, the rest are people I met in Ratinger Hof, a nearby bar. They were medical students, art historians, fashion designers, and so on.Portrait courtesy of Kunsthalle Wien, all other photos courtesy of Thomas Ruff

First of all, they don’t get a coffee—that makes their faces gaunt. We’ll talk for five minutes, then he or she sits on the chair. My camera is a plate camera, and that means I have to be under a black cloth. I do all the adjustments and then stand next to the camera. I tell them to look confident, but to be aware they are being photographed at this very moment. I give them slight corrective instructions, like to hold their chin higher or look a bit to the right side. Did your work with large portraiture lead directly into your nudes?

The nudes are the second most successful series right after the portraits. I assume again that the human face is interesting, and everybody has sex, or sexual preferences, wishes, and practices. So after the face, this is the next attraction, and that of course is why the nudes are so successful. How did they come about?

I came across the whole thing when I wanted to reflect on nude photography. I did internet research. If you type in “nude photography” you get to Helmut Newton and Peter Lindbergh. I found this was a little boring, the 19th-century heterosexual perspective of nice ladies at lakes. I searched on and accidentally stumbled across those teaser pages of porn sites. I felt they were much more honest than artsy nude photography—they got down to business. There are needs, and these needs have to be satisfied. What struck you most about internet porn?

I was surprised by the exhibitionism and voyeurism that was present on the web. I experimented with pixel adjustment at that time. When I transferred my gadgetry on one of the pictures, I had my first nude. I showed it to my girlfriend to see what she thought. She said, “Actually, shitty, but still good!” I thought this seemed interesting, so I downloaded more stuff and worked with it. I tried to work objectively and not just include my heterosexual male point of view, but to cover a whole spectrum of sexual practices and desires—to make it democratic. Heterosexual, homosexual, fetish, and so on. This eventually led to publishing. How did Nudes, the book you did with the novelist Michel Houellebecq, happen?

The publishing house Schirmer/Mosel wanted to do a book with the two of us. They originally wanted an article on nude photography, but I found it crappy and said that there’s no way it’s getting in, that the best would be to use one of Houellebecq’s texts, because I am a big fan of his. The publisher asked him directly if he could provide us with a literary piece for this book. But I wouldn’t call it collaboration. Sometime later Schirmer told me that Houellebecq is planning to do a soft porno and wants to consult me for technical problems. But that was about all. Do you pay attention to photography these days?

Actually, I am not that interested in photography. I am more interested in art. I’d rather go to art exhibitions. If it says “big photography exhibition,” I don’t even bother going in. Do you stay up-to-date with younger artists?

I don’t really stay updated. I am somehow too old for that and far too concerned with my own stuff.