* Now, we used the word “leper” here because we wanted to reference an old Metallica song. But you should know that people with leprosy consider that word really offensive. It carries a stigma that they’ve been trying to beat for years, and it’s outdated and ignorant. So next time you meet someone with leprosy, you are under no circumstances to call them a leper. When I arrived in Nepal, my ultimate destination was the Lalgadh Leprosy Hospital in the southeastern Terai Plain. But first, some Nepalese infighting necessitated delicate consideration of how to get there. You see, the Madheshi tribe, in an effort to get their calls for autonomy recognized by the official government, had been organizing strikes along all the highways. The last group of people to ignore these strikes was a bus load en route to a wedding. The vehicle ended up being burned to the ground with the driver and his assistant still inside. I would be heading down the same route, so we used a white jeep with white flags attached to the front and back, a giant red “H” for “hospital” painted on the hood, and a Madheshi local behind the wheel. Our camouflage worked and we made it to our destination, where a bunch of leprosy patients awaited me. Out of the frying pan and into the chronic infectious disease.

Lalgadh is the busiest leprosy hospital in the world. While the incidence of new leprosy cases is dropping significantly in India, South America, and Africa, in Lalgadh they still see a steady stream of up to 12 new cases a day. When we arrived, a patient named Makessor Mandal was in for a routine toe amputation. It was his fourth. Makessor has had leprosy for 20 years. Although cured now, his feet have been left completely anesthetized. He can stand in an open fire, tread on broken glass, and have a sugarcane spike the size of a cigar driven through his foot and never know about it until the flesh starts to rot and he’s woken up one morning by a repulsive smell coming from the end of his bed. Makessor was here this time, again, because someone told him his foot stank.

When I arrived in Nepal, my ultimate destination was the Lalgadh Leprosy Hospital in the southeastern Terai Plain. But first, some Nepalese infighting necessitated delicate consideration of how to get there. You see, the Madheshi tribe, in an effort to get their calls for autonomy recognized by the official government, had been organizing strikes along all the highways. The last group of people to ignore these strikes was a bus load en route to a wedding. The vehicle ended up being burned to the ground with the driver and his assistant still inside. I would be heading down the same route, so we used a white jeep with white flags attached to the front and back, a giant red “H” for “hospital” painted on the hood, and a Madheshi local behind the wheel. Our camouflage worked and we made it to our destination, where a bunch of leprosy patients awaited me. Out of the frying pan and into the chronic infectious disease.

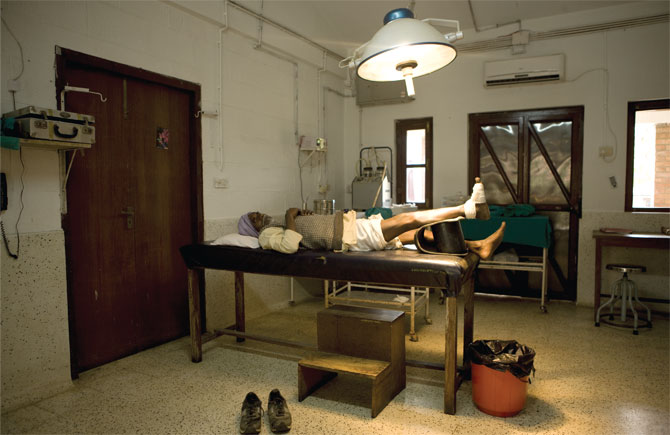

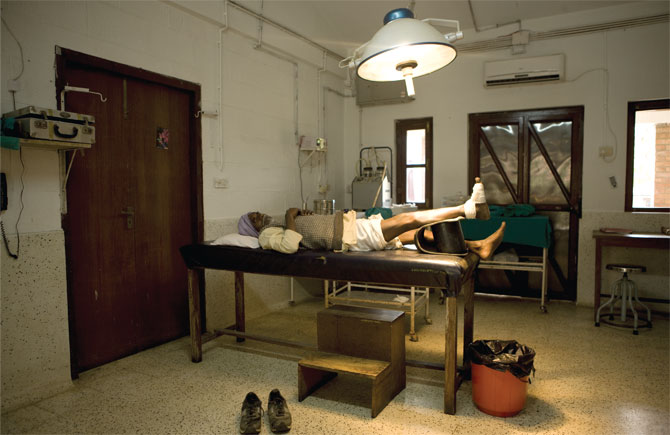

Lalgadh is the busiest leprosy hospital in the world. While the incidence of new leprosy cases is dropping significantly in India, South America, and Africa, in Lalgadh they still see a steady stream of up to 12 new cases a day. When we arrived, a patient named Makessor Mandal was in for a routine toe amputation. It was his fourth. Makessor has had leprosy for 20 years. Although cured now, his feet have been left completely anesthetized. He can stand in an open fire, tread on broken glass, and have a sugarcane spike the size of a cigar driven through his foot and never know about it until the flesh starts to rot and he’s woken up one morning by a repulsive smell coming from the end of his bed. Makessor was here this time, again, because someone told him his foot stank. While planning my trip to the land of the leprosy, I really expected that I would vomit the first time I saw a toe amputation. And now, here I was, about to put my theory to the test. It was a hot day, the lights in the operating room were low, and the smell of iodine was so strong that it felt like we were swimming in the stuff. But after a few fast dashes of the blade, a strong tug on the tiny white bone, and a thumbs-up between patient and doctor, it was all over. That’s it? Dr. Krishna placed the toe on a small tin tray for Makessor to see. It looked like an offering or a donation or the last cocktail sausage at a party, the one that never gets eaten because of absurd etiquette. Makessor smiled, like he was proud of his useless toe as it sat there. “We’re a bit like a prison for young offenders,” Dr. Krishna said, as he sewed the remaining skin up with a coil of fishing line, “We take them in, we treat their wounds, we care for them till they’re better, but we know they’ll be back sooner or later.”

“When were you here last?” he asked Makessor, who looked down at his foot and thought hard. “Last year,” Makessor said, “for the little toe.”

While planning my trip to the land of the leprosy, I really expected that I would vomit the first time I saw a toe amputation. And now, here I was, about to put my theory to the test. It was a hot day, the lights in the operating room were low, and the smell of iodine was so strong that it felt like we were swimming in the stuff. But after a few fast dashes of the blade, a strong tug on the tiny white bone, and a thumbs-up between patient and doctor, it was all over. That’s it? Dr. Krishna placed the toe on a small tin tray for Makessor to see. It looked like an offering or a donation or the last cocktail sausage at a party, the one that never gets eaten because of absurd etiquette. Makessor smiled, like he was proud of his useless toe as it sat there. “We’re a bit like a prison for young offenders,” Dr. Krishna said, as he sewed the remaining skin up with a coil of fishing line, “We take them in, we treat their wounds, we care for them till they’re better, but we know they’ll be back sooner or later.”

“When were you here last?” he asked Makessor, who looked down at his foot and thought hard. “Last year,” Makessor said, “for the little toe.” Lalgadh Leprosy Hospital began as a wooden hut on a patch of scrubland infested with scorpions, tarantulas, and cobras, under the funding of a charity called the Nepal Leprosy Trust. Fourteen years later, the scorpions are still there but the hospital’s expanded to house over 150 inpatients, the hospital staff, and all their families. For a compound that treats sufferers of one of the world’s most gruesome diseases, it’s a remarkably positive place—bucolic even, with birds singing in the trees, wild garlic plants spitting out their strong perfume, and buffalo lazing in the long grasses. On clear days, you can climb the watchtower and make out the small white tips of the Himalayas to the north. If it’s extremely clear, you might even convince yourself that you can pick out Everest from the lineup. Staff and their children play soccer in the cool evening on a proper field with goalposts, the patients sit down together to eat huge plates of dahl baht and rice in the canteen, and the only moans in the middle of the night come from randy jackals skirting the perimeter fence. “Tranquil” is the first word to come to mind when you arrive at the hospital. It’s easy to forget that it treats one of the most nightmarish diseases that the vengeful gods have ever bestowed upon us puny mortals. But while it may be pretty from the outside, the hospital’s wards and operating rooms are a wee bit less lovely, what with chicken wire for windows, beds that are more rust than metal, and an X-ray machine so old it’s dangerous for both patient and operator. The doctors perform skin grafts and amputations under single-bulb lamps that give off about as much light as a mobile phone. They have two theaters: the “clean” one and the “dirty” one. The dirty one is where they do amputations.

Lalgadh Leprosy Hospital began as a wooden hut on a patch of scrubland infested with scorpions, tarantulas, and cobras, under the funding of a charity called the Nepal Leprosy Trust. Fourteen years later, the scorpions are still there but the hospital’s expanded to house over 150 inpatients, the hospital staff, and all their families. For a compound that treats sufferers of one of the world’s most gruesome diseases, it’s a remarkably positive place—bucolic even, with birds singing in the trees, wild garlic plants spitting out their strong perfume, and buffalo lazing in the long grasses. On clear days, you can climb the watchtower and make out the small white tips of the Himalayas to the north. If it’s extremely clear, you might even convince yourself that you can pick out Everest from the lineup. Staff and their children play soccer in the cool evening on a proper field with goalposts, the patients sit down together to eat huge plates of dahl baht and rice in the canteen, and the only moans in the middle of the night come from randy jackals skirting the perimeter fence. “Tranquil” is the first word to come to mind when you arrive at the hospital. It’s easy to forget that it treats one of the most nightmarish diseases that the vengeful gods have ever bestowed upon us puny mortals. But while it may be pretty from the outside, the hospital’s wards and operating rooms are a wee bit less lovely, what with chicken wire for windows, beds that are more rust than metal, and an X-ray machine so old it’s dangerous for both patient and operator. The doctors perform skin grafts and amputations under single-bulb lamps that give off about as much light as a mobile phone. They have two theaters: the “clean” one and the “dirty” one. The dirty one is where they do amputations. “Leprosy is worse than AIDS,” says Graeme Cugston, the Australian director of the hospital, “At least with AIDS, after a year or so without treatment, you die. With leprosy you just keep on going. It’s a living hell.” The disease starts to work on the peripheries of the body: toes, fingers, eyelids, and skin. The leprosy bacteria causes an auto-destructive reaction in the body’s immune system, which starts to eat away at itself in an effort to shake the infection. What this effectively leads to is rotting from the outside in. It’s like a literal version of biting off your nose to spite your face. As the disease progresses, the skin desensitizes. This is where the real problems, like Makessor’s feet, begin. If you don’t feel pain, how can you protect yourself?

“Leprosy is worse than AIDS,” says Graeme Cugston, the Australian director of the hospital, “At least with AIDS, after a year or so without treatment, you die. With leprosy you just keep on going. It’s a living hell.” The disease starts to work on the peripheries of the body: toes, fingers, eyelids, and skin. The leprosy bacteria causes an auto-destructive reaction in the body’s immune system, which starts to eat away at itself in an effort to shake the infection. What this effectively leads to is rotting from the outside in. It’s like a literal version of biting off your nose to spite your face. As the disease progresses, the skin desensitizes. This is where the real problems, like Makessor’s feet, begin. If you don’t feel pain, how can you protect yourself? Bakumari is one of the most critically affected patients at the hospital. She can’t tell you how old she is, but she knows that she was born the same year as the great earthquake of Nepal (which was in 1934). She is a tiny woman with short gray hair and frail limbs that poke out from under her sari like the branches of a blackthorn tree. She has had leprosy for 14 years. “I thought it was a curse of God,” she says. The hospital has been treating her for about five years now, and part of her program involves education about leprosy—teaching her that it’s not a form of divine punishment or karma but a disease that anyone can get. For the time being, Bakumari remains unconvinced. “I know that leprosy is a disease,” she says, “but I still think maybe I was cursed.”

To look at her, it’d be hard to disagree. She has no sensation in her feet or her hands and was left blind after her eyelids disintegrated, allowing infection to attack. Talking to her on the small stone stoop outside her ward, flies land on her nose and eye sockets. She doesn’t feel them. A cobra could slide out of the grass and wrap itself around her feet and she wouldn’t have a clue. Bakumari is a wonderful, intelligent lady who, like all dear grannies, could talk the legs off a table, but physically she is less capable than a two-year-old. The saddest thing for the staff at Lalgadh is that Bakumari’s physical destruction could have been easily prevented.

Bakumari is one of the most critically affected patients at the hospital. She can’t tell you how old she is, but she knows that she was born the same year as the great earthquake of Nepal (which was in 1934). She is a tiny woman with short gray hair and frail limbs that poke out from under her sari like the branches of a blackthorn tree. She has had leprosy for 14 years. “I thought it was a curse of God,” she says. The hospital has been treating her for about five years now, and part of her program involves education about leprosy—teaching her that it’s not a form of divine punishment or karma but a disease that anyone can get. For the time being, Bakumari remains unconvinced. “I know that leprosy is a disease,” she says, “but I still think maybe I was cursed.”

To look at her, it’d be hard to disagree. She has no sensation in her feet or her hands and was left blind after her eyelids disintegrated, allowing infection to attack. Talking to her on the small stone stoop outside her ward, flies land on her nose and eye sockets. She doesn’t feel them. A cobra could slide out of the grass and wrap itself around her feet and she wouldn’t have a clue. Bakumari is a wonderful, intelligent lady who, like all dear grannies, could talk the legs off a table, but physically she is less capable than a two-year-old. The saddest thing for the staff at Lalgadh is that Bakumari’s physical destruction could have been easily prevented. Leprosy is very easily cured. A six-month multidrug program flushes the bacteria out of your system for life. It’s an incredibly harsh combination. The side effects include hepatitis, psychosis, a violent reaction in which the skin peels off, and diarrhea so bad that the patient has to literally sleep in a bedpan for a few days. But hey, you won’t be leprous any longer when it’s over. If taken in time, someone with leprosy can escape the physical deformities associated with the disease. The reason it often isn’t taken early is because the stigma of leprosy is so bad that people prefer to cover it up rather than go to a hospital and get cured. In Nepal, if someone in your family has had leprosy—even your grandparents—the chances of you getting married or even landing a job are greatly reduced. It’s like having an uncle who went nuts and shot up the post office. People just assume the fruit can’t have fallen that far from the tree. A large part of the stigma is attributable to the hospitals themselves. Lalgadh wouldn’t be so busy if it weren’t for the fact that doctors and nurses from every other hospital in southern Nepal turn away anyone who displays even the early symptoms of leprosy.

Leprosy is only mildly contagious, and it only affects people with very low immune systems. The chances of a healthy Nepalese person catching leprosy are remote; the chances of a Western person catching it are about as likely as a piano dropping from the sky on top of your head. The United States has new cases of leprosy every year, but all of these are from recently arrived African or South American immigrants. Your average picket-fence, Applebee’s American family has nothing to fear from leprosy. But in the remote countryside of Nepal, where subsistence agriculture is the norm, malnourishment is common, and the only certainty is the daily blackout, maintaining a strong immune system and avoiding disease is not easy.

Leprosy is very easily cured. A six-month multidrug program flushes the bacteria out of your system for life. It’s an incredibly harsh combination. The side effects include hepatitis, psychosis, a violent reaction in which the skin peels off, and diarrhea so bad that the patient has to literally sleep in a bedpan for a few days. But hey, you won’t be leprous any longer when it’s over. If taken in time, someone with leprosy can escape the physical deformities associated with the disease. The reason it often isn’t taken early is because the stigma of leprosy is so bad that people prefer to cover it up rather than go to a hospital and get cured. In Nepal, if someone in your family has had leprosy—even your grandparents—the chances of you getting married or even landing a job are greatly reduced. It’s like having an uncle who went nuts and shot up the post office. People just assume the fruit can’t have fallen that far from the tree. A large part of the stigma is attributable to the hospitals themselves. Lalgadh wouldn’t be so busy if it weren’t for the fact that doctors and nurses from every other hospital in southern Nepal turn away anyone who displays even the early symptoms of leprosy.

Leprosy is only mildly contagious, and it only affects people with very low immune systems. The chances of a healthy Nepalese person catching leprosy are remote; the chances of a Western person catching it are about as likely as a piano dropping from the sky on top of your head. The United States has new cases of leprosy every year, but all of these are from recently arrived African or South American immigrants. Your average picket-fence, Applebee’s American family has nothing to fear from leprosy. But in the remote countryside of Nepal, where subsistence agriculture is the norm, malnourishment is common, and the only certainty is the daily blackout, maintaining a strong immune system and avoiding disease is not easy. The hospital’s head caregiver is Dr. Krishna. He was born in a leper colony to parents who both had leprosy. His mother had deformed claw hands and one leg. His grandparents had leprosy too. “I think that’s why my resistance is so strong,” he says and then adds jokingly, “But I still check my arms for spots every now and then.”

“It was really hard growing up,” he says. “My father had no deformities and he worked and my mother was on her own raising the family. Other children called me a leper in the streets.” Krishna is living proof of how international aid can work. A Swiss and a Dutch charity helped put him through school, before Nepal Leprosy Trust took him on and sent him for training as a doctor. The hospital’s lab technician is also a son of leprosy, as are all of the nurses. They work for half the salary they would get in one of the state hospitals. If everyone gets paid, even if it’s only half of what they should be getting, it’s been a good month. As well as not being able to cover staff wages, they don’t always have bandages, plastic gloves, or fishing wire for sewing flesh back together. In spite of this, the level of care they extend to the patients at the hospital can lead one to believe the staff were employed by an exclusive clinic, somewhere the rich and the idle might go to dry out for a couple of weeks.

The World Health Organization has called leprosy a neglected disease. Money that might ordinarily have gone into funding the hospital, finding a leprosy vaccine, starting stigma-elimination courses, or helping rehabilitate the 2 million leprosy sufferers in the world is being siphoned elsewhere.

Cancer has Bill Gates, AIDS has Bono, and orphans have Angelina Jolie and Madonna snapping them up like handbags on sale, but leprosy has no visible public supporters. The WHO has a “Final Push” strategy for leprosy elimination with self-diagnosis and multidrug therapy at its core. The last big disease that science managed to eradicate was smallpox. That was nearly three decades ago. Ridding the world of leprosy would be a major boon for an organization that’s been slacking off like French truck drivers for way too long. There is a sense of urgency among experts that now is the time to act, before the disease mutates or becomes resistant to the multidrug therapy. When asked if he can imagine the end of leprosy in his lifetime, Dr. Krishna smiles. “Leprosy is a mystery,” he says. “It’s always been a mystery. In my lifetime, I don’t know. In my children’s, maybe yes.”

The hospital’s head caregiver is Dr. Krishna. He was born in a leper colony to parents who both had leprosy. His mother had deformed claw hands and one leg. His grandparents had leprosy too. “I think that’s why my resistance is so strong,” he says and then adds jokingly, “But I still check my arms for spots every now and then.”

“It was really hard growing up,” he says. “My father had no deformities and he worked and my mother was on her own raising the family. Other children called me a leper in the streets.” Krishna is living proof of how international aid can work. A Swiss and a Dutch charity helped put him through school, before Nepal Leprosy Trust took him on and sent him for training as a doctor. The hospital’s lab technician is also a son of leprosy, as are all of the nurses. They work for half the salary they would get in one of the state hospitals. If everyone gets paid, even if it’s only half of what they should be getting, it’s been a good month. As well as not being able to cover staff wages, they don’t always have bandages, plastic gloves, or fishing wire for sewing flesh back together. In spite of this, the level of care they extend to the patients at the hospital can lead one to believe the staff were employed by an exclusive clinic, somewhere the rich and the idle might go to dry out for a couple of weeks.

The World Health Organization has called leprosy a neglected disease. Money that might ordinarily have gone into funding the hospital, finding a leprosy vaccine, starting stigma-elimination courses, or helping rehabilitate the 2 million leprosy sufferers in the world is being siphoned elsewhere.

Cancer has Bill Gates, AIDS has Bono, and orphans have Angelina Jolie and Madonna snapping them up like handbags on sale, but leprosy has no visible public supporters. The WHO has a “Final Push” strategy for leprosy elimination with self-diagnosis and multidrug therapy at its core. The last big disease that science managed to eradicate was smallpox. That was nearly three decades ago. Ridding the world of leprosy would be a major boon for an organization that’s been slacking off like French truck drivers for way too long. There is a sense of urgency among experts that now is the time to act, before the disease mutates or becomes resistant to the multidrug therapy. When asked if he can imagine the end of leprosy in his lifetime, Dr. Krishna smiles. “Leprosy is a mystery,” he says. “It’s always been a mystery. In my lifetime, I don’t know. In my children’s, maybe yes.”

Advertisement

Advertisement