SIOUX CITY, Iowa — Deb Fegenbush was praying she would win the lottery. The odds were 1 in 292 million, but the jackpot was $92 million, more than enough to keep the Planned Parenthood clinic she manages in the Morningside neighborhood here open.“I’m never lucky, but I did buy a Powerball ticket today,” Fegenbush said from behind her desk in a small makeshift office when I visited last month, on the last day the clinic would see patients before closing for good on June 30. “If I won the lottery, I could continue to help Planned Parenthood.”Sioux City is one of four Planned Parenthood clinics in Iowa that are shutting down after Gov. Terry Branstad signed a bill in May to “defund” the healthcare organization. Dozens of states have introduced similar measures targeting Planned Parenthood in the past couple of years, and a few, like Texas and Missouri, have succeeded. Kicking Planned Parenthood off Medicaid and “defunding” the organization has repeatedly come up in Congress as well. As the Senate lurches toward a vote on repealing the Affordable Care Act, the fight to strip Planned Parenthood of public money remains one of the most divisive.No line item in the federal budget goes to Planned Parenthood. Rather, the organization gets government funding through Medicaid reimbursements and public family planning grants. Planned Parenthood received $2 million of the $3 million the federal government gave to Iowa each year to reimburse organizations that provided family planning for lower-income patients for things like contraception and STI testing. When the state budget bill rejected this federal money — making Iowa one of the first states to do so — the loss meant Planned Parenthood had to scale back. It set June 30, the end of its 2017 fiscal year, as the close-down day.Planned Parenthood of the Heartland, the affiliate covering Iowa and Nebraska, estimates that the closures in Iowa will affect care for 14,600 patients, 79 percent of whom are low-income. Twenty-nine employees are losing their jobs.“What’s happening in Iowa is a harrowing preview of what could become reality for millions of people around the country should the Senate pass Trumpcare,” Cecile Richards, the president of Planned Parenthood Action Fund, the organization’s national advocacy arm, said in an email. “If Trumpcare is passed into law, we’ll see that kind of devastation happen nationwide, with far too many women simply going without the healthcare they need.”I visited two of Iowa’s closing clinics during their last week to see what it means for staff and patients when politicians force Planned Parenthood to shut its doors. Even though eight other locations will remain open in Iowa, along with two clinics in neighboring Nebraska, everyone I talked to expressed a mixture of anger, frustration, grief, and concern — for their patients, for their communities, and for the fate of reproductive healthcare in America. I turned right at the Super 8 onto Stone Avenue and accidentally drove past the clinic’s steep driveway, so I made a U-Turn in the parking lot of Mary’s Choice, the crisis pregnancy center next door. Sioux City is situated on the west side of the state, right on the border and across the Missouri river from Nebraska. The drive to the clinic had taken me past leafy neighborhoods dotted with quaint homes, churches, and strip malls.Planned Parenthood of Sioux City is surrounded by a tall wooden fence, which I’m told was erected to prevent the Mary’s Choice people from broadcasting the clinic’s parking lot activity on the local Catholic radio station. The clinic wouldn’t start seeing patients until noon, so the waiting room was empty when I walked in at 10 a.m. On an average day, the clinic saw around 20 patients, but today they expected only a handful. The woman who checked me in looked extremely glum. Fegenbush let me into the back where we walked past stacks of boxes and decommissioned exam rooms to the tiny windowless room she was using to work as she packed up her office.Fegenbush is 60 years old, with brownish-blondish hair. She was wearing jeans, a patterned pink top, and a bracelet on her right wrist with a cross on it. She started working at Planned Parenthood as a nurse in 2005 and was promoted to manager in 2009. Before that, she’d worked in an OB postpartum-neonatal unit for 22 years at a regional hospital.Fegenbush has five children and 10 grandchildren, attends church regularly as an evangelical Christian, and loves “The Ellen Show.” The notion that because she worked at Planned Parenthood some would consider her a radical, or even a murderer, is frankly absurd.She said she was only vaguely familiar with the organization before she began working here, but she quickly fell in love with the job because it gave her the opportunity to see patients in an intimate, one-on-one setting and develop long-term relationships. She finds it bewildering that something as essential as providing reproductive healthcare has become so controversial.“When I first started, I did not feel like my work was at risk at all,” she said. “It’s just been the last couple of years that everything has been about defunding Planned Parenthood, ending Planned Parenthood. Their actual goal is to get rid of us because they are hoping there will be no more abortions, and that’s all that matters.”Iowa is known as a bellwether state, where what people think and how they vote indicates how trends will unfold across the country. Iowans, or at least the Iowans I talked to, pride themselves on being sensible, level-headed, and practical people. The state has a long progressive history, but Republicans won control over the state Legislature last year, marking the first time since 1998 that the party held majorities in both chambers and the governor’s office.In less than six months, they used that control to pass an appropriations bill that rejected federal family planning money. The big sticking point was abortion — lawmakers didn’t want providers who performed abortions to get any public money at all, no matter that a rule called the Hyde Amendment has prohibited federal funding from going to pay for abortions since 1977.In rejecting this money, the lawmakers eliminated a program called the Iowa Family Planning Network, which allowed people to enroll in Medicaid for family planning services, including pap smears, birth control counseling, pregnancy tests, pelvic exams, and STD treatment. The program was meant to bridge the gap for people who didn’t qualify for Medicaid but also couldn’t afford private insurance or whose insurance didn’t cover these services. Planned Parenthood served 30 percent of the 12,000 people who received care through this program last year, so it had to go.Now that IFPN patients could no longer go to Planned Parenthood (unless they paid out of pocket), Planned Parenthood faced a shortfall. The leadership decided to close the clinics in Sioux City, Bettendorf, Burlington, and Keokuk, where many patients belonged to the now-defunct family planning program.Fegenbush said she understands why Planned Parenthood made the decision that it did, but that doesn’t make it any less devastating. “At 60 years old, I was hoping I could be here until I retired,” she said. “Now I need to be looking for a job somewhere.”Losing her job was stressful, but talking about the patients really made Fegenbush emotional. She mentioned one patient who had been coming to the clinic for 24 years, since she was 13 years old. The woman cried at her last appointment because she didn’t know what to do. Fegenbush said their postman also cried when he heard the news — a Planned Parenthood nurse had encouraged his wife to get a mammogram and gave her a referral. The mammogram revealed breast cancer, and detecting it saved her life.“I’m really worried about those patients that have absolutely no insurance,” Fegenbush said. “I’m not saying what we do couldn’t happen at any other clinic — except it can’t happen at any other clinic, because if you don’t have insurance, no one will see you.” Today, 6.3 percent of Iowa adults are uninsured, half the rate before the passage of the Affordable Care Act. And the Iowa Hospital Association estimates that between 200,000 and 250,000 Iowa residents will lose coverage if the Republicans repeal Obamacare.Fegenbush is also worried about younger patients, especially teens who won’t stop having sex but might be scared to tell their parents they want birth control. She’s concerned the rates of unplanned pregnancies and STDs — which are lower in Iowa than the national average — will go up, and that people like the postman’s wife won’t discover they have cancer until it’s too late.

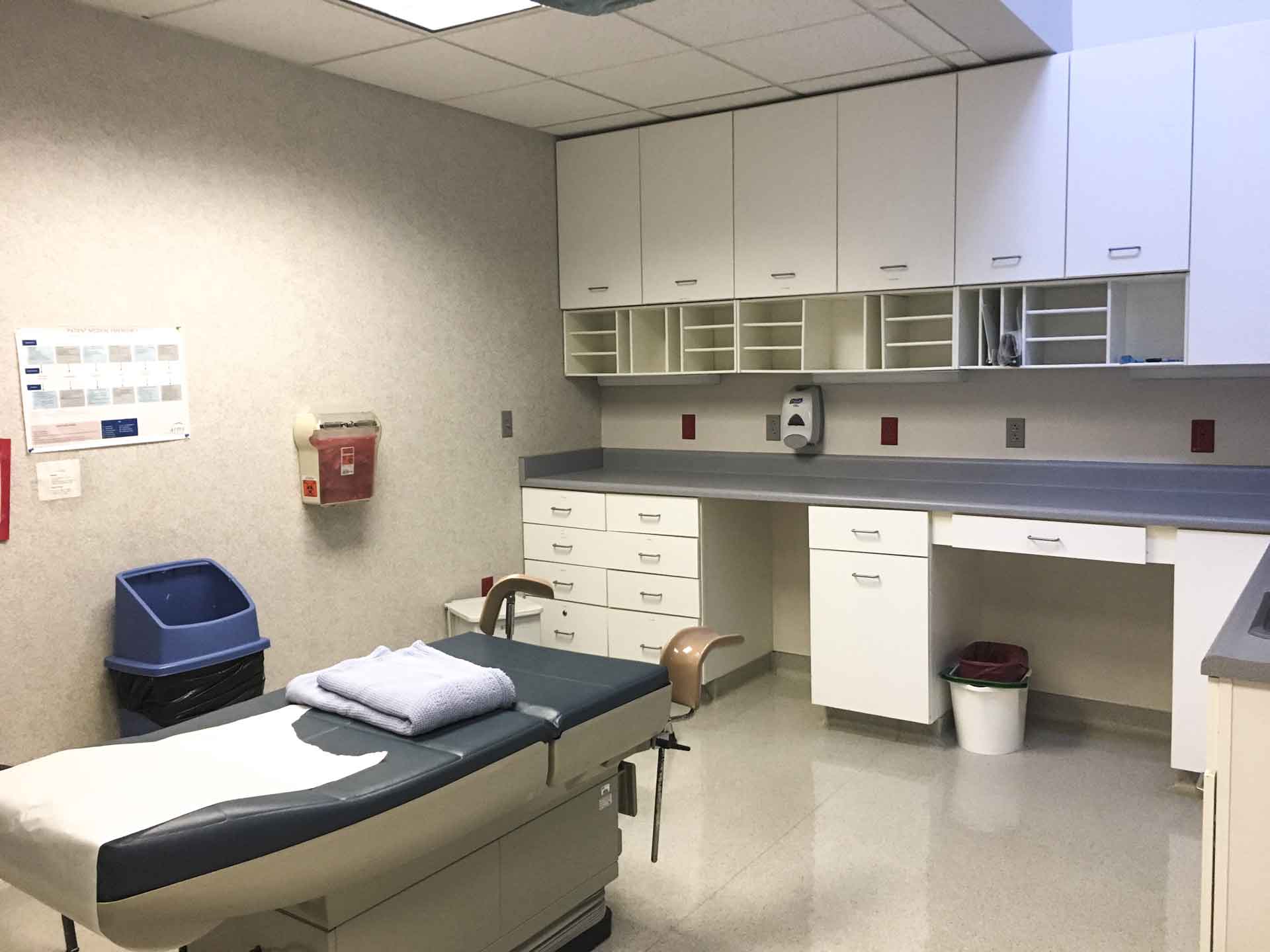

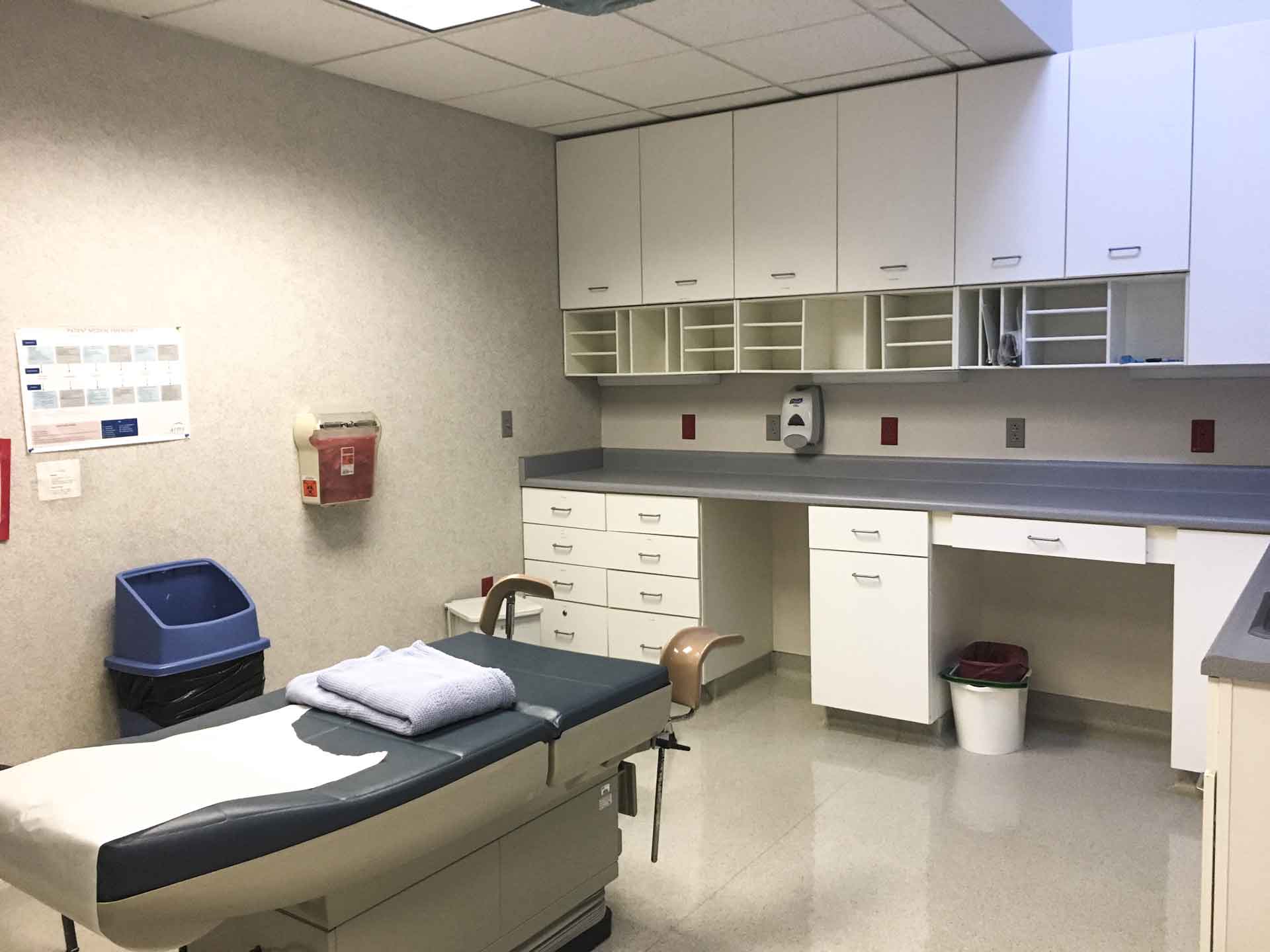

I turned right at the Super 8 onto Stone Avenue and accidentally drove past the clinic’s steep driveway, so I made a U-Turn in the parking lot of Mary’s Choice, the crisis pregnancy center next door. Sioux City is situated on the west side of the state, right on the border and across the Missouri river from Nebraska. The drive to the clinic had taken me past leafy neighborhoods dotted with quaint homes, churches, and strip malls.Planned Parenthood of Sioux City is surrounded by a tall wooden fence, which I’m told was erected to prevent the Mary’s Choice people from broadcasting the clinic’s parking lot activity on the local Catholic radio station. The clinic wouldn’t start seeing patients until noon, so the waiting room was empty when I walked in at 10 a.m. On an average day, the clinic saw around 20 patients, but today they expected only a handful. The woman who checked me in looked extremely glum. Fegenbush let me into the back where we walked past stacks of boxes and decommissioned exam rooms to the tiny windowless room she was using to work as she packed up her office.Fegenbush is 60 years old, with brownish-blondish hair. She was wearing jeans, a patterned pink top, and a bracelet on her right wrist with a cross on it. She started working at Planned Parenthood as a nurse in 2005 and was promoted to manager in 2009. Before that, she’d worked in an OB postpartum-neonatal unit for 22 years at a regional hospital.Fegenbush has five children and 10 grandchildren, attends church regularly as an evangelical Christian, and loves “The Ellen Show.” The notion that because she worked at Planned Parenthood some would consider her a radical, or even a murderer, is frankly absurd.She said she was only vaguely familiar with the organization before she began working here, but she quickly fell in love with the job because it gave her the opportunity to see patients in an intimate, one-on-one setting and develop long-term relationships. She finds it bewildering that something as essential as providing reproductive healthcare has become so controversial.“When I first started, I did not feel like my work was at risk at all,” she said. “It’s just been the last couple of years that everything has been about defunding Planned Parenthood, ending Planned Parenthood. Their actual goal is to get rid of us because they are hoping there will be no more abortions, and that’s all that matters.”Iowa is known as a bellwether state, where what people think and how they vote indicates how trends will unfold across the country. Iowans, or at least the Iowans I talked to, pride themselves on being sensible, level-headed, and practical people. The state has a long progressive history, but Republicans won control over the state Legislature last year, marking the first time since 1998 that the party held majorities in both chambers and the governor’s office.In less than six months, they used that control to pass an appropriations bill that rejected federal family planning money. The big sticking point was abortion — lawmakers didn’t want providers who performed abortions to get any public money at all, no matter that a rule called the Hyde Amendment has prohibited federal funding from going to pay for abortions since 1977.In rejecting this money, the lawmakers eliminated a program called the Iowa Family Planning Network, which allowed people to enroll in Medicaid for family planning services, including pap smears, birth control counseling, pregnancy tests, pelvic exams, and STD treatment. The program was meant to bridge the gap for people who didn’t qualify for Medicaid but also couldn’t afford private insurance or whose insurance didn’t cover these services. Planned Parenthood served 30 percent of the 12,000 people who received care through this program last year, so it had to go.Now that IFPN patients could no longer go to Planned Parenthood (unless they paid out of pocket), Planned Parenthood faced a shortfall. The leadership decided to close the clinics in Sioux City, Bettendorf, Burlington, and Keokuk, where many patients belonged to the now-defunct family planning program.Fegenbush said she understands why Planned Parenthood made the decision that it did, but that doesn’t make it any less devastating. “At 60 years old, I was hoping I could be here until I retired,” she said. “Now I need to be looking for a job somewhere.”Losing her job was stressful, but talking about the patients really made Fegenbush emotional. She mentioned one patient who had been coming to the clinic for 24 years, since she was 13 years old. The woman cried at her last appointment because she didn’t know what to do. Fegenbush said their postman also cried when he heard the news — a Planned Parenthood nurse had encouraged his wife to get a mammogram and gave her a referral. The mammogram revealed breast cancer, and detecting it saved her life.“I’m really worried about those patients that have absolutely no insurance,” Fegenbush said. “I’m not saying what we do couldn’t happen at any other clinic — except it can’t happen at any other clinic, because if you don’t have insurance, no one will see you.” Today, 6.3 percent of Iowa adults are uninsured, half the rate before the passage of the Affordable Care Act. And the Iowa Hospital Association estimates that between 200,000 and 250,000 Iowa residents will lose coverage if the Republicans repeal Obamacare.Fegenbush is also worried about younger patients, especially teens who won’t stop having sex but might be scared to tell their parents they want birth control. She’s concerned the rates of unplanned pregnancies and STDs — which are lower in Iowa than the national average — will go up, and that people like the postman’s wife won’t discover they have cancer until it’s too late. About half the patients that Planned Parenthood sees in Iowa are low-income and rely on services that are subsidized or free. Supporters of “defunding” have claimed that other healthcare providers can fill the void, but recent investigations by the Des Moines Register and The Atlantic put the lie to this claim. The Iowa Department of Human Services put out a list/Default.aspx) of alternative providers for the counties where Planned Parenthood is closing, and some doctors were more than 100 miles away. Others were at Catholic facilities that don’t provide family planning services, and at least one provider on the list was closed.In Sioux City, a local medical center called Siouxland Community Health is supposed to pick up the slack, but Fegenbush is skeptical that it will be able to handle a higher volume of patients or match her clinic in expertise. Planned Parenthood’s patients skew female, young, and low-income. Talking with young women about their preferred method of birth control or concerns about HPV is worlds away from the services community health centers tend to provide — diagnosing strep throat, setting a broken limb, managing diabetes.Brendyn Richards, the director of development and advocacy at Siouxland Community Health, said they already receive 100,000 patient visits a year. As soon as news broke about the Planned Parenthood closures, Siouxland started receiving calls from patients asking if they could come there instead for care. “It’s definitely something we’ve talked about — can we take on these patients?” Richards said in a phone interview. “I think we can, but we don’t know yet how many of their thousands of patients will end up coming here.”Siouxland Community Health won’t include abortion in its options when counseling women with unplanned pregnancies because it doesn’t want to lose its public funding. For abortion care, patients in Sioux City will have to drive about 90 minutes to another Planned Parenthood center.“Some of our patients will stay with Planned Parenthood and drive to the locations in Omaha or Council Bluffs, but there are some people who can’t utilize that option,” Fegenbush said. “Those are the ones that are in tears when they leave, who are afraid. They say, ‘What will I do?’ And our answer is, ‘I’m really sorry.’”

About half the patients that Planned Parenthood sees in Iowa are low-income and rely on services that are subsidized or free. Supporters of “defunding” have claimed that other healthcare providers can fill the void, but recent investigations by the Des Moines Register and The Atlantic put the lie to this claim. The Iowa Department of Human Services put out a list/Default.aspx) of alternative providers for the counties where Planned Parenthood is closing, and some doctors were more than 100 miles away. Others were at Catholic facilities that don’t provide family planning services, and at least one provider on the list was closed.In Sioux City, a local medical center called Siouxland Community Health is supposed to pick up the slack, but Fegenbush is skeptical that it will be able to handle a higher volume of patients or match her clinic in expertise. Planned Parenthood’s patients skew female, young, and low-income. Talking with young women about their preferred method of birth control or concerns about HPV is worlds away from the services community health centers tend to provide — diagnosing strep throat, setting a broken limb, managing diabetes.Brendyn Richards, the director of development and advocacy at Siouxland Community Health, said they already receive 100,000 patient visits a year. As soon as news broke about the Planned Parenthood closures, Siouxland started receiving calls from patients asking if they could come there instead for care. “It’s definitely something we’ve talked about — can we take on these patients?” Richards said in a phone interview. “I think we can, but we don’t know yet how many of their thousands of patients will end up coming here.”Siouxland Community Health won’t include abortion in its options when counseling women with unplanned pregnancies because it doesn’t want to lose its public funding. For abortion care, patients in Sioux City will have to drive about 90 minutes to another Planned Parenthood center.“Some of our patients will stay with Planned Parenthood and drive to the locations in Omaha or Council Bluffs, but there are some people who can’t utilize that option,” Fegenbush said. “Those are the ones that are in tears when they leave, who are afraid. They say, ‘What will I do?’ And our answer is, ‘I’m really sorry.’” Fegenbush ushered me out of the clinic promptly at noon, before the patients started arriving, and I began the 370-mile drive across the state to Bettendorf, one of the Quad Cities on the border with Illinois. The metropolitan area is home to about 425,000 people and is bisected by the Mississippi River. It feels much more urban than Sioux City, with a smattering of casinos, arts centers, museums, and theaters.The first thing I noticed when I drove up to Planned Parenthood Quad Cities was the For Sale sign. There were only a few cars in the sprawling parking lot, but this clinic seemed less dormant than the Sioux City location. There were a few patients in the waiting room, and I could feel the buzz of a health center at work. The clinic had stretched its budget to avoid closing like the others on June 30; instead it will stay open, with reduced hours, until the building sells or until Dec. 31, whichever comes first.Angela Rodriguez-Finch, the manager, is petite, with brown hair and warm brown eyes, wearing scrubs and an air of authority. She joined Planned Parenthood in 2011 after serving in the same role at a nearby YMCA. Like Deb Fegenbush, she has lived in Iowa her entire life. Rodriguez-Finch is the youngest child of 11, and her upbringing is part of why she feels so strongly about reproductive freedom. Her mother first got pregnant when she was 17 and her family sent her away to have the baby.“She had the baby, got back, and got married, but it was an abusive relationship,” Rodriguez-Finch said. “When my mother would go to her doctor, she begged him and cried and said, ‘You can save my life. I want birth control.’ She was completely depressed and couldn’t work because she had all these children. And he was like, ‘Nope, you just need to not have sex.’”When Rodriguez-Finch woke up the morning after the election in November, she said, she knew things were going to be bad for Planned Parenthood. But the news that the Quad Cities clinic was closing still came as a shock. The clinic is busy and the team didn’t think they were on the chopping block.The Legislature’s decision to revoke Planned Parenthood’s funding is not a mandate from the people. In a February poll, 77 percent of adult Iowans said they favored continued state funding for Planned Parenthood, up 3 percentage points from the same time last year. That included 62 percent of Republicans and 62 percent of evangelical Christians. Since the bill was passed, people have come out in marches and rallies protesting the defunding, but none of it has seemed to make a difference.“We are proud of the efforts of the Legislature approving more than $3.2 million for women’s healthcare clinics that do not perform abortions,” Ben Hammes, a spokesman for the governor, said in May. “The [anti-abortion] movement is making tremendous strides in changing the hearts and minds, to return to a culture that once again respects human life. There are 2,400 different doctors, nurses, and clinics in every corner of the state that can provide family planning services.”Rodriguez-Finch said the notion that Planned Parenthood’s patients, particularly those without insurance, can simply go someplace else is “maddening, ludicrous, and insane.”The previous week, she told me, the clinic saw a patient who was raped while on vacation in Mexico. She came to Planned Parenthood for STI testing and wanted an antiretroviral medication that, if taken within 72 hours, can help prevent HIV. The clinic had closed early that day so the staff could go out for a goodbye lunch, but the patient was having trouble finding a pharmacy that stocked the medicine. The clinic’s nurses left the lunch and spent the next four hours tracking it down.“Who else would do that?” Rodriguez-Finch asked. “That’s just one example, and it just happened and now we are closing.”Rodriguez-Finch gave me a tour of the clinic — past a wall of postcards from patients saying how sorry they are to see the clinic go — and then walked me into the nurse’s office, where I met Laurie Brown. She answered my questions as she popped in and out to see patients.Brown has long, wavy brown hair and light blue eyes. She looks like the older sister every girl wishes she had, which is part of why she connects so well with patients. It’s also why she’s so sad to leave.“I feel like the rug has been swept out from underneath me,” she said. “I’ve had a month to process it and I’m still in shock. I feel like we are being forced to throw our hands in the air and leave our patients stranded, and that’s not what we are about.”Even though as a nurse, she has plenty of job prospects, she loves working with the population Planned Parenthood serves; she sees education as a big part of her job.Brown said the impending closure has changed the information they now give to patients. When a woman comes in and asks for a Depo-Provera shot, the nurses have to discuss how she plans to get her follow-up shot three months later. They’ve also noticed an uptick in patients requesting long-acting reversible contraceptives, like IUDs, because they’re concerned it’ll be harder to get other forms of birth control. The staff is trying to help patients figure out how they will continue to get care, but it’s impossible to reach everyone. They’re worried about the patients who call or show up in the next few months to find the clinic has closed.As I sat in the nurse’s office, I watched a few of the staff members clear out their desks, filling boxes with books, “thank you” notes from patients, and the general bric-a-brac that workspaces inevitably accrue. The physician’s assistant, Lauren Zenisek, jokingly asked if I wanted to take a plastic uterus model as a souvenir.Zenisek will continue to pitch in at Planned Parenthood’s Iowa City clinic, which is expecting an uptick in patients after Quad Cities closes. Brown will have to find work elsewhere. Rodriguez-Finch is staying on with Planned Parenthood to become the regional director of the Omaha area. She plans to rent an apartment in Omaha, 300 miles away, while her husband and high school-age son stay at their home in the Quad Cities.During deliberations in May, the Nebraska state Legislature removed a budget item that would have allowed state officials to reduce or eliminate funding for the state’s two Planned Parenthood clinics, but who knows what could happen next year. Especially if more states follow Iowa’s example or if Congress manages to boot Planned Parenthood from Medicaid altogether.“I’m moving with caution,” Rodriguez-Finch said. “You just don’t know, because the situation is so volatile right now. How scary is that? I’m super happy to have this opportunity, but I’m putting that little asterisk on the end. It’s a slippery, scary slope. This is me today, but it’s you tomorrow.”Rebecca Grant is a freelance journalist based in Brooklyn who covers reproductive rights, women’s health, and gender-based violence.

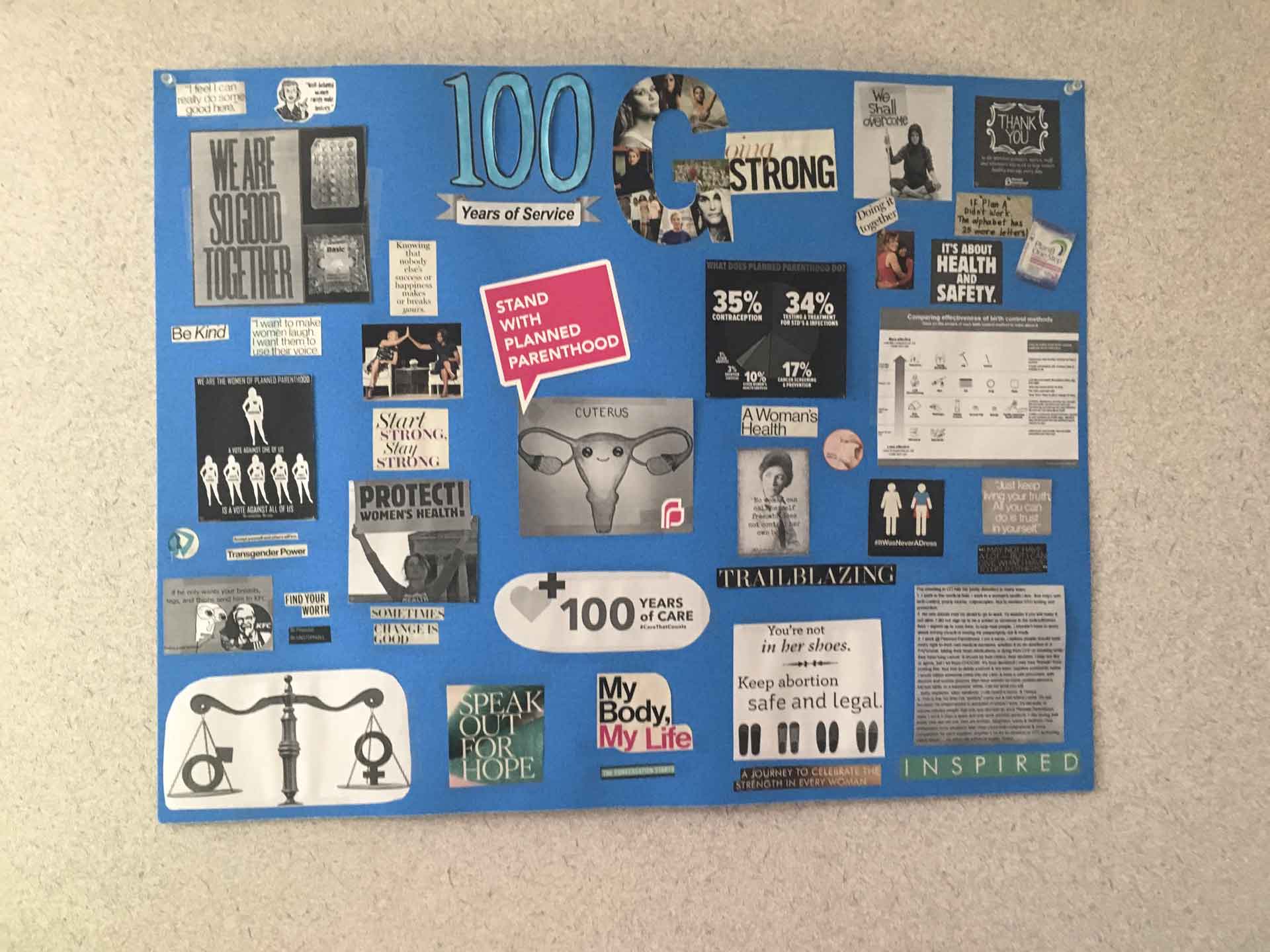

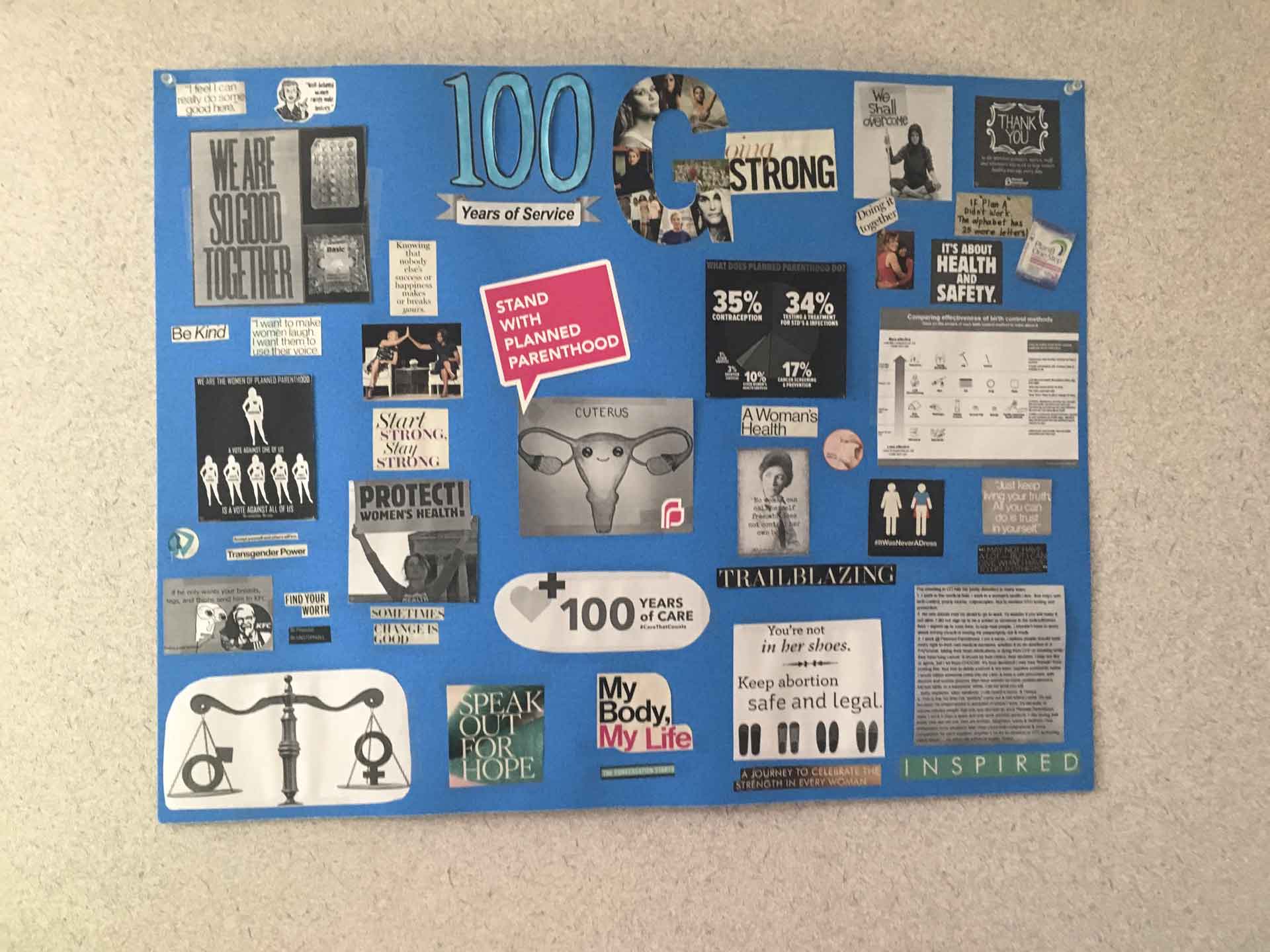

Fegenbush ushered me out of the clinic promptly at noon, before the patients started arriving, and I began the 370-mile drive across the state to Bettendorf, one of the Quad Cities on the border with Illinois. The metropolitan area is home to about 425,000 people and is bisected by the Mississippi River. It feels much more urban than Sioux City, with a smattering of casinos, arts centers, museums, and theaters.The first thing I noticed when I drove up to Planned Parenthood Quad Cities was the For Sale sign. There were only a few cars in the sprawling parking lot, but this clinic seemed less dormant than the Sioux City location. There were a few patients in the waiting room, and I could feel the buzz of a health center at work. The clinic had stretched its budget to avoid closing like the others on June 30; instead it will stay open, with reduced hours, until the building sells or until Dec. 31, whichever comes first.Angela Rodriguez-Finch, the manager, is petite, with brown hair and warm brown eyes, wearing scrubs and an air of authority. She joined Planned Parenthood in 2011 after serving in the same role at a nearby YMCA. Like Deb Fegenbush, she has lived in Iowa her entire life. Rodriguez-Finch is the youngest child of 11, and her upbringing is part of why she feels so strongly about reproductive freedom. Her mother first got pregnant when she was 17 and her family sent her away to have the baby.“She had the baby, got back, and got married, but it was an abusive relationship,” Rodriguez-Finch said. “When my mother would go to her doctor, she begged him and cried and said, ‘You can save my life. I want birth control.’ She was completely depressed and couldn’t work because she had all these children. And he was like, ‘Nope, you just need to not have sex.’”When Rodriguez-Finch woke up the morning after the election in November, she said, she knew things were going to be bad for Planned Parenthood. But the news that the Quad Cities clinic was closing still came as a shock. The clinic is busy and the team didn’t think they were on the chopping block.The Legislature’s decision to revoke Planned Parenthood’s funding is not a mandate from the people. In a February poll, 77 percent of adult Iowans said they favored continued state funding for Planned Parenthood, up 3 percentage points from the same time last year. That included 62 percent of Republicans and 62 percent of evangelical Christians. Since the bill was passed, people have come out in marches and rallies protesting the defunding, but none of it has seemed to make a difference.“We are proud of the efforts of the Legislature approving more than $3.2 million for women’s healthcare clinics that do not perform abortions,” Ben Hammes, a spokesman for the governor, said in May. “The [anti-abortion] movement is making tremendous strides in changing the hearts and minds, to return to a culture that once again respects human life. There are 2,400 different doctors, nurses, and clinics in every corner of the state that can provide family planning services.”Rodriguez-Finch said the notion that Planned Parenthood’s patients, particularly those without insurance, can simply go someplace else is “maddening, ludicrous, and insane.”The previous week, she told me, the clinic saw a patient who was raped while on vacation in Mexico. She came to Planned Parenthood for STI testing and wanted an antiretroviral medication that, if taken within 72 hours, can help prevent HIV. The clinic had closed early that day so the staff could go out for a goodbye lunch, but the patient was having trouble finding a pharmacy that stocked the medicine. The clinic’s nurses left the lunch and spent the next four hours tracking it down.“Who else would do that?” Rodriguez-Finch asked. “That’s just one example, and it just happened and now we are closing.”Rodriguez-Finch gave me a tour of the clinic — past a wall of postcards from patients saying how sorry they are to see the clinic go — and then walked me into the nurse’s office, where I met Laurie Brown. She answered my questions as she popped in and out to see patients.Brown has long, wavy brown hair and light blue eyes. She looks like the older sister every girl wishes she had, which is part of why she connects so well with patients. It’s also why she’s so sad to leave.“I feel like the rug has been swept out from underneath me,” she said. “I’ve had a month to process it and I’m still in shock. I feel like we are being forced to throw our hands in the air and leave our patients stranded, and that’s not what we are about.”Even though as a nurse, she has plenty of job prospects, she loves working with the population Planned Parenthood serves; she sees education as a big part of her job.Brown said the impending closure has changed the information they now give to patients. When a woman comes in and asks for a Depo-Provera shot, the nurses have to discuss how she plans to get her follow-up shot three months later. They’ve also noticed an uptick in patients requesting long-acting reversible contraceptives, like IUDs, because they’re concerned it’ll be harder to get other forms of birth control. The staff is trying to help patients figure out how they will continue to get care, but it’s impossible to reach everyone. They’re worried about the patients who call or show up in the next few months to find the clinic has closed.As I sat in the nurse’s office, I watched a few of the staff members clear out their desks, filling boxes with books, “thank you” notes from patients, and the general bric-a-brac that workspaces inevitably accrue. The physician’s assistant, Lauren Zenisek, jokingly asked if I wanted to take a plastic uterus model as a souvenir.Zenisek will continue to pitch in at Planned Parenthood’s Iowa City clinic, which is expecting an uptick in patients after Quad Cities closes. Brown will have to find work elsewhere. Rodriguez-Finch is staying on with Planned Parenthood to become the regional director of the Omaha area. She plans to rent an apartment in Omaha, 300 miles away, while her husband and high school-age son stay at their home in the Quad Cities.During deliberations in May, the Nebraska state Legislature removed a budget item that would have allowed state officials to reduce or eliminate funding for the state’s two Planned Parenthood clinics, but who knows what could happen next year. Especially if more states follow Iowa’s example or if Congress manages to boot Planned Parenthood from Medicaid altogether.“I’m moving with caution,” Rodriguez-Finch said. “You just don’t know, because the situation is so volatile right now. How scary is that? I’m super happy to have this opportunity, but I’m putting that little asterisk on the end. It’s a slippery, scary slope. This is me today, but it’s you tomorrow.”Rebecca Grant is a freelance journalist based in Brooklyn who covers reproductive rights, women’s health, and gender-based violence.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement