Stephen Dupont: Yeah, it was 1989. I was 22 and my partner at the time introduced me to this guy Ben Bohane. Ben was a writer and we just hit it off straight away. We were both young and eager to travel so we teamed up and decided to go and cover the Vietnamese withdrawal from Cambodia, which was this huge event in 1989. We managed to get interest from Playboy Magazine. They ended up publishing the story along with the pictures, so it was our first paid gig. We thought it was pretty rock ‘n’ roll going in for Playboy. [chuckles]I bet. How long were you there for?

About a month. We got our visas in Bangkok and we headed off to the airport. I can’t remember exactly, but either the plane was full or we missed it. I think we were late. I remember we kicked up a stink because this was our first gig, so we were thinking, “How the fuck are we gonna go?” We waved our credentials and said, “We’re big time journalists and we need to get over and cover this story!” We weren’t, we were just trying to pull as many strings as we could. God knows how it happened but they gave us our own plane. Ben and I were the only two passengers on it and they flew us straight into Saigon—It was amazing.Do you remember the first conflict zone you worked in?

The first kind of real ‘under fire’ moment was in Sri Lanka in 1990. I wanted to cover the civil war between the government forces and the Tamil Tigers. I was really young and naive. I was so eager to see some action and photograph it. I hired this pink motorcycle from Colombo and drove all the way up to the North. I’d been given some papers from the Sri Lankan military that allowed me through check points, but the only thing I had for the Tamil Tigers was a few names of their commanders—you couldn’t really contact them. I was just hoping I’d cross over and hook up with them.

I didn’t. Maybe I had a sense, because I ended up heading away from whoever was shooting at me. I crashed my bike down this ravine where a group of soldiers were hunkered down. I actually had no idea who these guys were, they weren’t in uniform or anything and I actually thought I was with the Tamil Tigers. I remember thinking, “Fuck… I’ve found them.” They ended up being government troops, just a rag-tag mercenary group. I was in shock because I’d never been shot at before—it was really full on! [chuckles]What happened next?

The government forces told me they were pulling back. So I said, “Well, I need to get to the Tamil Tigers because that’s what I’m here for.” They told me to just head back towards the shooting. So I got on my bike and slowly started chugging along the road. I got about halfway and the shooting started again. I could hear the whizzing of the bullets as they passed inches from my head.

I think essentially it was the beauty of the people and the landscape, also the history of the place. I’d read a lot about it and it was one of my major places of interest in '93. It was the beginning of the civil war and I felt that it wasn’t getting any coverage even though the war was absolutely full on at that stage. Kabul was basically a city under siege; it was being bombed quite heavily as these three or four different Mujahedeen factions fought for control.

I got on a chopper with the wounded back to Jalalabad. Paul was already there being treated by the American doctors. As soon as I landed I was confronted by the Australian Federal Police—the Department of Foreign Affairs had already announced that two Australian journalists had been killed. I was really fucking pissed off because I wasn’t dead and neither was Paul!I had my mobile phone on me so I called home and told my partner, “Whatever you hear on the news, it’s not true—you’re hearing my voice right now. I’m alive, Paul’s really badly wounded, but I’m not dead.”What ended up happening to Paul?

Paul got really serious head injuries. He caught shrapnel all through his body. He is incredibly lucky to be alive. He still has lot of shrapnel left in him that they can’t take out. When you have a bombing it’s not just metal in the projectiles but people’s bones and flesh as well. It was one of the most horrific scenes I have ever witnessed.

In some ways I think I have but it certainly hasn’t put me off going into warzones and taking risks. I’ve been in many situations where I’ve nearly been killed and you come out thinking, “Fuck, how did I survive that and how many lives do I have left?” I often feel that way, and that scares me. It’s the law of averages, it’s going to get you at some point. It’s a euphoric, amazing feeling of survival when you get out of a situation like that, where you actually feel like you are going to die and you don’t. I rely on my experience and my gut feelings to not necessarily save me, but prevent me from getting into situations like that.How do you tell your family about something like that?

It’s always hard; I tend not to say too much. My partner Lizzy has worked in warzones before so I speak to her about things, my daughter is too young to hear this stuff but when she’s older I’ll be happy to talk about it with her. I don’t believe in hiding from my family, if something needs to be said it needs to be said.

Once it was all over I went back to revisit the whole thing from the notes in my diary. The fact that I was being filmed that morning in the hotel makes me think it was highly likely that we were targeted. It all makes total sense now. It’s definitely possible.What was probably your most controversial photograph was taken in 2005 in Afghanistan, of American soldiers burning the bodies of dead Taliban fighters. What happened that day?

Well, I was embedded with the 173rd Airborne; we were heading to a really contested, Taliban-infested area in Shawali Kowt, Kandahar. I was actually attached to PSYOPs, which was phenomenal. I was thinking, “Are you fucking kidding me?!” I could not believe it, it was like all my Christmases had come at once.What’s PSYOPs?

Psychological operations. It’s a unit within the US military. It’s almost CIA-esque. They kind of taunt the enemy—they’re involved in torture, interviewing people, jails. They get information by various methods. They also communicate with the enemy by dropping leaflets from helicopters and announcing things over loudspeakers. Psychological shit.Ok cool. So they put you with PSYOPs…

Yeah, I couldn’t believe it. We left Kandahar Airbase with fucking AC/DC’s “Hell’s Bells” and Metallica, all this heavy metal blaring out the Humvees. It was great. We got to this small village called Gonbaz, where there had been a battle about three hours before we arrived. In the morning I woke up with PSYOPs doing their thing, taunting the enemy with these really weird fucking recordings, really loud across the valley. Sounds of babies crying and dogs howling—it was kind of sinister.

Then they started to make an announcement of the bodies burning: “We’re burning your brothers facing west”, and all this other kind of shit. They were telling me they were burning the bodies for hygiene reasons, which is highly possible, but whether PSYOPs just used that as an excuse to make the most of the situation I don’t know. I don’t think they were burning the bodies specifically to make this huge fucking statement, but I’ll never know.So I started taking pictures and shooting video, as the bodies were burning quite quickly. It turned into a massive story and was published in the New York Times, but it was the video that went all over the world. It was on every network in America. It was a big deal and it went right to the top.

They were reprimanded and some of them were charged. It was a hard thing for me to do because I came out thinking that the US Military were going to hate me and would never let me back in. All these guys were getting charged who I got on really well with—they’d befriended me. I had to deal with a lot when that came out, it’s a tough decision to make but I had to honour journalism, I had to honour who I am. I didn’t like it, but it was important.Would you do it again?

Well yes I would. That for me is absolute integrity. If I was faced with another event like that I would photograph it and document it in its truest way.

Yeah I probably do. Dreams are obscure and surreal at the best of times so I can’t specifically say what those dreams are about, but yes I dream about war; both while I’m at home and while I’m there. It’s very difficult to digest what dreams mean and how they come. They can come in a much more domesticated situation but have elements of conflict, or can be directly related to conflicts I’ve been in.I’ve had quite a few dreams of running under fire—usually trying to get a photograph and missing it—or dreams of trying to catch a plane and things are preventing you from getting there. I’m going through something like that now actually. I’m about to head to the Philippines to cover the typhoon that just went through. It’s basically all I’m thinking about and I’m just trying to get everything prepared.I read dreams as just anxiety or pressure. Usually it’s the night before you leave, you tend not to have a very good sleep and you wake up well before your alarm goes off.

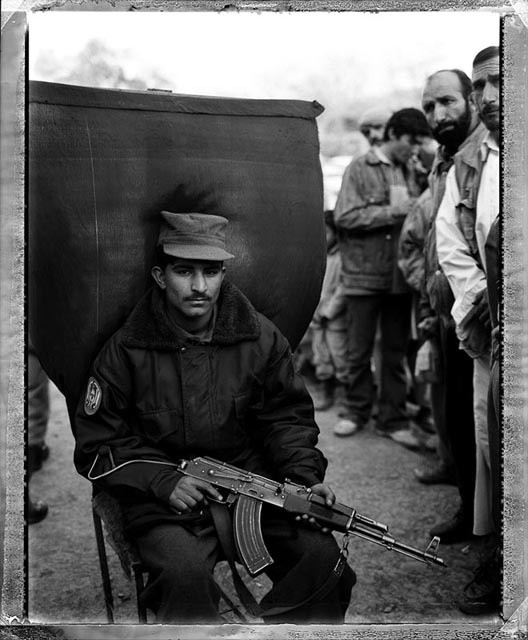

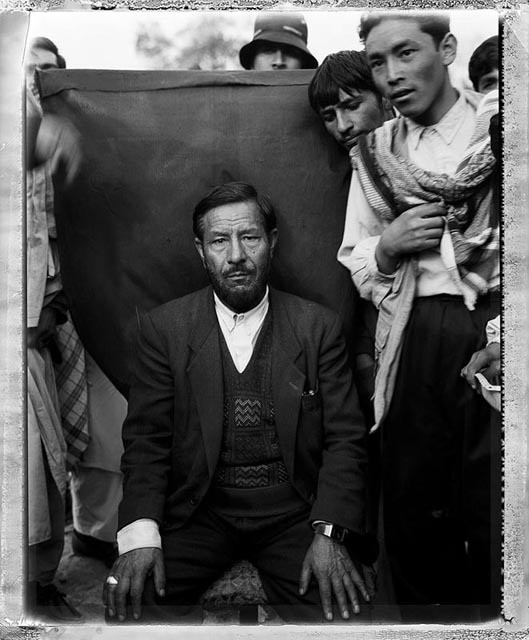

Northern Alliance leader Ahmed Shah Massoud, Faizabad, 1998

US Troops burn two dead Taliban fighters following a battle outside the village of Gonbaz, Kandihar, 2005.

A Northern Alliance tank rolls through the town of Jabal as Saraj, 2001.

Afghan soldiers on a hilltop in Kunar Province, 2005.

A map of Afghanistan on silk purchased in a US military PX store in Kabul, 2009.

A triptych of Sing-Sing performers at the Mt Hagen Show, Papua New Guinea, 2004.

Sgt John Ingels of Weapons Platoon poses for a portrait as part of Stephen's “Why Am I A Marine?” series.

US Marines on patrol in Asadabad, Kunar Province, 2005.

A patient inside the mental asylum of Papa Kitoko, Luanda, Angola, 1993.

A patient’s foot in chains inside Papa Kitoko’s mental asylum, Luanda, Angola.

Weapons Platoon of the US Marine Corp in FOB Castle, Helmand, 2009

Psy Ops leaflets from the US Army to be dropped onto rural areas and villages in Afghanistan, 2005.