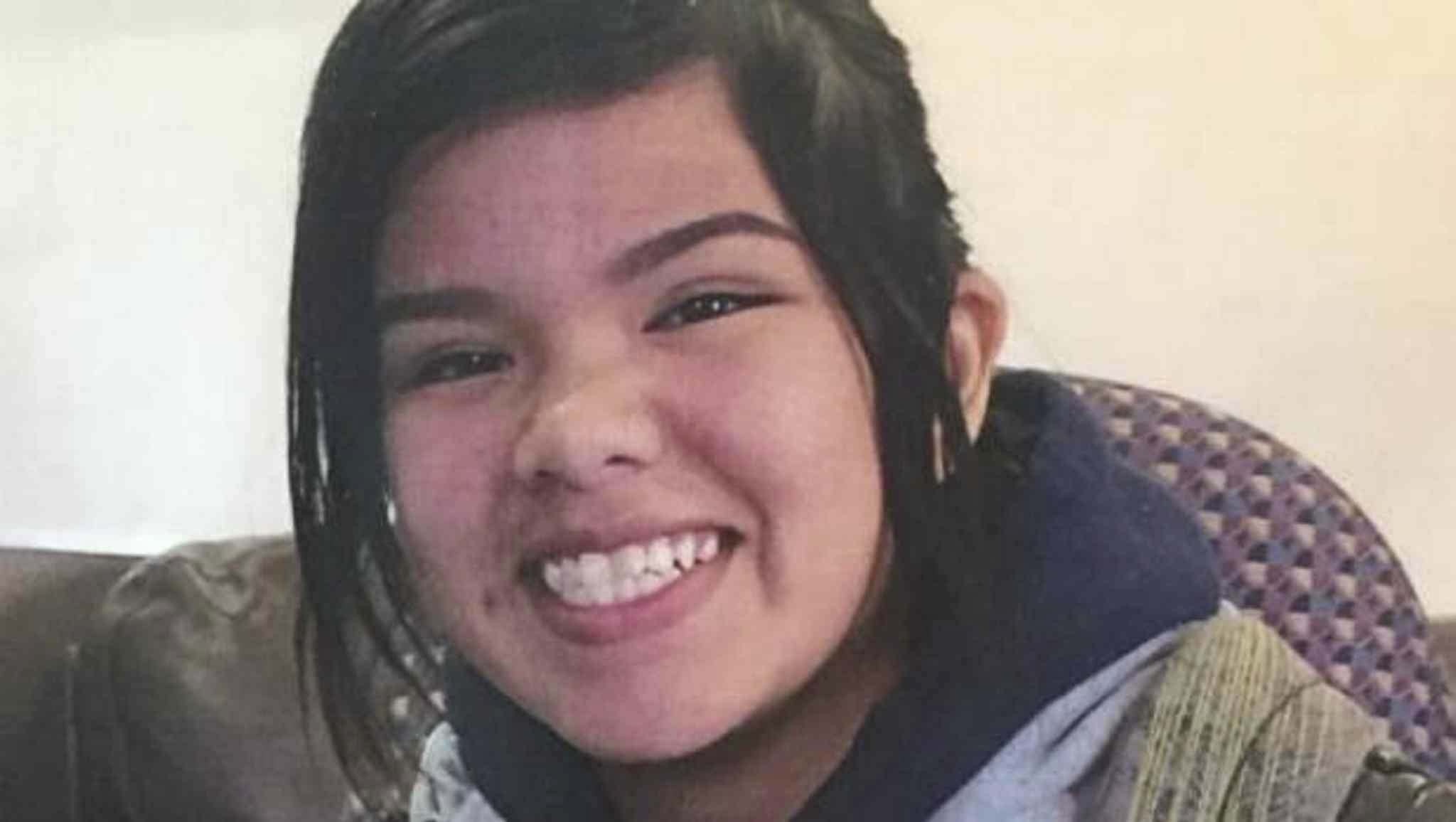

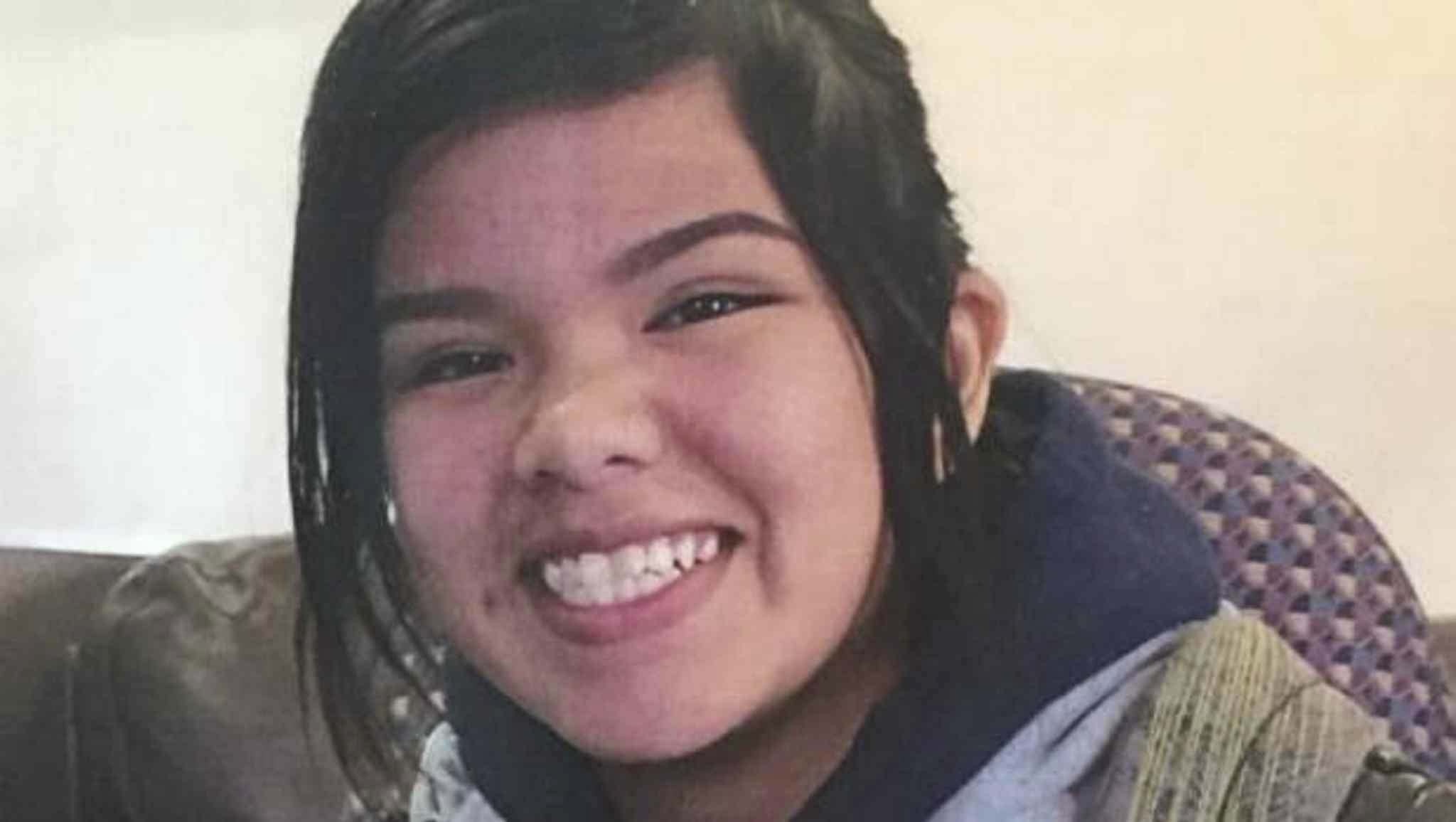

Azraya Kokopenace’s family is still desperately searching for answers.One year ago, the 14-year-old’s body was found hanging in a tree directly across the street from the hospital where police brought her two days earlier, in the midst of a mental health crisis.But there is still no public explanation for how she died, still no understanding of what happened in those final hours.In the absence of that, Azraya’s family is pointing the finger at the three public agencies that had been caring for the teen in the lead up to her death — the police, the hospital, and a child welfare service — and demanding a public inquest.Those agencies are staying quiet about her case, and the regional coroner tells VICE News his decision on whether to grant an inquest is still months away.“She fell through the cracks, and they seem to be fairly big cracks between the agencies,” said Glenn Stuart, the family’s lawyer. It’s still not clear whose custody Azraya was in when she died, he added. The family said she had been living in a group home run by Anishinaabe Abinoojii Family Services.After an extensive search, on April 17 a local Bear Clan Patrol member spotted her body in the wooded park. The roof of the hospital is visible from the foot of the tree. Police have closed their case, concluding no foul play. They declined an interview request and refused to disclose information about their policies. The executive director of Anishinaabe Abinoojii Family Services, a provincially mandated child welfare service, was unreachable for an interview.Mark Balcaen, president and CEO of Lake of the Woods District Hospital, told VICE News they have a patient transfer protocol with OPP that states if an officer believes a patient is at a low risk for violence, they transfer the responsibility of care to the hospital. Under the hospital’s shared protocols with child welfare services, if a child is receiving medical care at the hospital, the child welfare agency is called in to provide guardianship and monitoring.Patients under 16 years old must have a guardian sign a consent to treatment form. “If a patient, hastily or with some forethought, decides to leave treatment then our staff will work within ethical and legal boundaries to balance patient safety and staff safety,” Balcaen said. “Police will be called to search for a missing patient who may be considered a potential harm to themselves or others.”Michael Wilson, regional supervising coroner for Ontario’s northern region, told VICE News his investigation into Azraya’s death is done, and he has reviewed reports from all three agencies involved, but he is waiting for a final review by the internal pediatric death committee before he can decided if there will be an inquest.It can take six months to a year to decide whether to order an inquest, Wilson said. He said a decision in this case could be a few months away, “but obviously I can’t guarantee what is out of my control.”The roles of intersecting agencies make this case more complex, he said. He would not confirm whether she was in custody at the time of her death, or the cause of death.“It’s difficult to do this in a public forum, and I hope you don’t take this personally against the media, but this is something that is better addressed with the family directly,” he said. “This is particularly important in a case that it may go to inquest, in which case the information and evidence should come out properly in an inquest court, and if not, the answers that we provide are to the family, and as they desire to share, with the further community.”

Police have closed their case, concluding no foul play. They declined an interview request and refused to disclose information about their policies. The executive director of Anishinaabe Abinoojii Family Services, a provincially mandated child welfare service, was unreachable for an interview.Mark Balcaen, president and CEO of Lake of the Woods District Hospital, told VICE News they have a patient transfer protocol with OPP that states if an officer believes a patient is at a low risk for violence, they transfer the responsibility of care to the hospital. Under the hospital’s shared protocols with child welfare services, if a child is receiving medical care at the hospital, the child welfare agency is called in to provide guardianship and monitoring.Patients under 16 years old must have a guardian sign a consent to treatment form. “If a patient, hastily or with some forethought, decides to leave treatment then our staff will work within ethical and legal boundaries to balance patient safety and staff safety,” Balcaen said. “Police will be called to search for a missing patient who may be considered a potential harm to themselves or others.”Michael Wilson, regional supervising coroner for Ontario’s northern region, told VICE News his investigation into Azraya’s death is done, and he has reviewed reports from all three agencies involved, but he is waiting for a final review by the internal pediatric death committee before he can decided if there will be an inquest.It can take six months to a year to decide whether to order an inquest, Wilson said. He said a decision in this case could be a few months away, “but obviously I can’t guarantee what is out of my control.”The roles of intersecting agencies make this case more complex, he said. He would not confirm whether she was in custody at the time of her death, or the cause of death.“It’s difficult to do this in a public forum, and I hope you don’t take this personally against the media, but this is something that is better addressed with the family directly,” he said. “This is particularly important in a case that it may go to inquest, in which case the information and evidence should come out properly in an inquest court, and if not, the answers that we provide are to the family, and as they desire to share, with the further community.” Her family says those answers should be public by now. “What are they hiding? That’s my question to them, because all of us deserve an answer,” Azraya’s aunt said.The hospital, police and the coroner’s office each extended their condolences to the family in statements to VICE News.Azraya’s family will remember her at a vigil Monday evening in Kenora.“She was so proud to go to pow-wows,” her aunt remembered, choking up as she spoke. “She would have her jingle dress on and she would ask me to go dance with her out in the circle. And she would dance her hardest and her best beside me. And she would smile at me. Did she ever look so beautiful in her jingle dress.”“She would always give me these hugs,” she continued. “I call them orangutan hugs because she would dangle on me. I really miss those hugs.”

Her family says those answers should be public by now. “What are they hiding? That’s my question to them, because all of us deserve an answer,” Azraya’s aunt said.The hospital, police and the coroner’s office each extended their condolences to the family in statements to VICE News.Azraya’s family will remember her at a vigil Monday evening in Kenora.“She was so proud to go to pow-wows,” her aunt remembered, choking up as she spoke. “She would have her jingle dress on and she would ask me to go dance with her out in the circle. And she would dance her hardest and her best beside me. And she would smile at me. Did she ever look so beautiful in her jingle dress.”“She would always give me these hugs,” she continued. “I call them orangutan hugs because she would dangle on me. I really miss those hugs.”

Advertisement

“She was ignored, and she wasn’t taken seriously,” her aunt Lorenda Kokopenace told VICE News. Aboriginal people in Kenora face racism on a daily basis, she said, and three of her own family members have died in police custody. “If she had been a different race, I really feel that they would have [followed] protocols and given her better treatment.”Video footage made public last year showed Azraya in an altercation with police, during which two officers pinned her to the ground. About three weeks later, on the night of April 15, Kenora OPP went looking for the girl because she was out past her 9 p.m. curfew, according to her family. When the officers found the teen, who had a history of suicide attempts, they brought her to the Lake of the Woods District Hospital because she was in distress. Police would not confirm these events to VICE News. But they did say that around 11:20 p.m. that night, the girl left the hospital and was seen entering a small wooded park across the street.“She was ignored, and she wasn’t taken seriously.”

Advertisement

“It’s difficult to do this in a public forum … this is something that is better addressed with the family directly.”

Advertisement