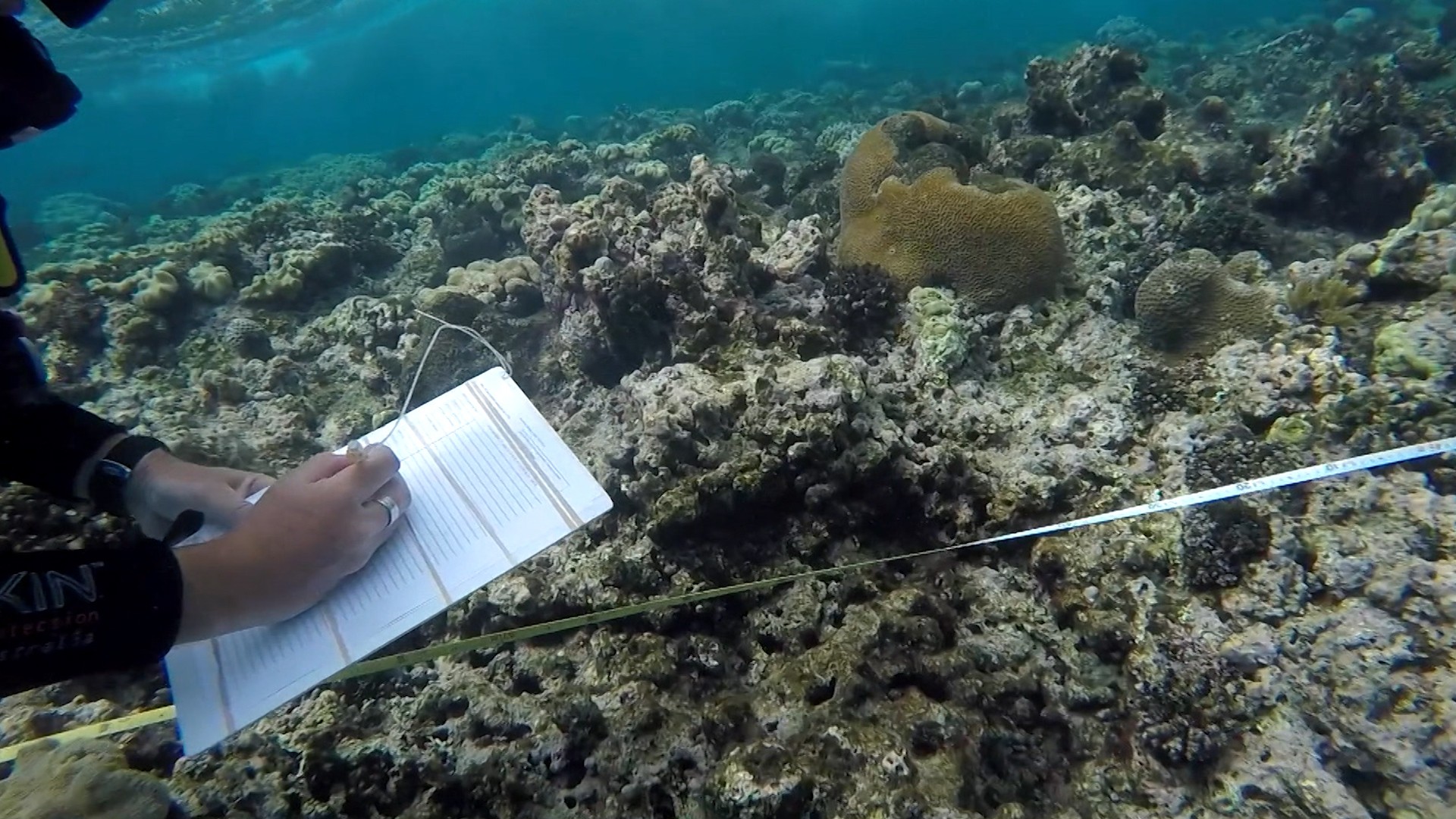

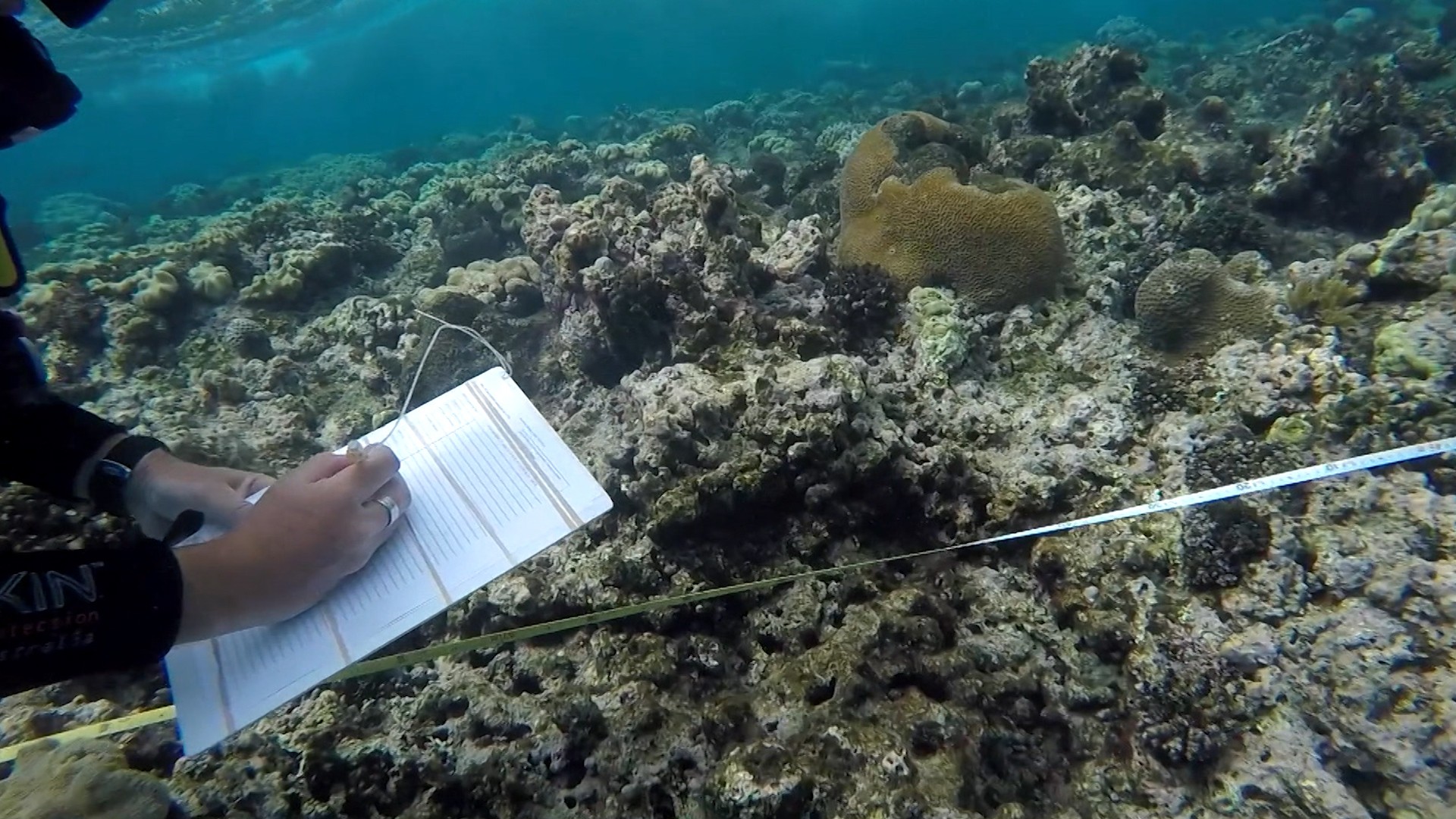

Want the best of VICE News straight to your inbox? Sign up here.Caitlin Maratea has been diving off the west coast of Maui every day for nearly ten years. But the reefs where she leads dive tours are dying, and she’s watching it happen in real time.“Every year, it just seems like the amount of dead corals and the amount of algae overgrowth is increasing in a striking way,” said Maratea, who owns Banyan Tree Divers. “You can see where the reef used to sit, and now it just looks like a skeleton of what was once there.”Maratea testified in front of the Maui City Council in September about the culprit for the reefs’ destruction: millions of gallons of sewage that runs off every day from the nearby wastewater treatment plant in Lahaina. The nutrient-rich sewage spilling into the waters allows algae to proliferate and suffocate the coral reefs. A nonprofit sued, arguing that the plant was polluting illegally, but the County of Maui, which runs the plant, insists it’s not doing anything wrong.Now, the Supreme Court will decide the fate of the reefs — and potentially blow a hole in the Clean Water Act.The case, County of Maui v. Hawai’i Wildlife Fund, centers on the fact that the sewage from the wastewater treatment plant first flows through municipal groundwater before reaching the ocean. Because the runoff doesn’t flow directly into the federally regulated waters, the county argues that the wastewater plant isn’t subject to regulation under the Clean Water Act.The Trump administration, which has already rolled back other clean water regulations, is weighing in on the County of Maui’s side. And, to explain what’s at stake, a Department of Justice attorney offered a metaphor during oral arguments in the case earlier this month: Imagine you want to spike the punch at a party.“If at my home, I pour whiskey from a bottle into a flask and then I bring the flask to a party at a different location, and I pour whiskey into the punch bowl there, nobody would say that I had added whiskey to the punch from the bottle,” the attorney, Malcolm Stewart, said.The Clean Water Act regulates what’s referred to as “point source” pollution, which comes directly from an identifiable polluter. If that pollution runs through groundwater, the County of Maui argues, it no longer comes from a point source — the whiskey bottle, in the Trump administration’s analogy. So as long as a polluter isn’t dumping directly into federally regulated waters, they wouldn’t need a permit.During arguments in front of the high court earlier this month, Justice Stephen Breyer noted that Maui’s position could essentially open up a loophole in the act. “All we do is we just cut off the pipes or whatever, five feet from the ocean,” he said. “You understand the problem.”The question that the justices appeared to be weighing is where exactly to draw the line on what is point source pollution and what isn’t. If pollution flows over ground and into water, everyone agreed that it should be regulated. But if it flows into another body of water and then into federally regulated waters, they weren’t so sure.Industry experts (and some of the Supreme Court justices) are concerned that regulating pollution that flows into groundwater and then into water regulated under the Clean Water Act could widely expand the applicability of the law. Groundwater across the country is largely unregulated, and, depending on how this decision swings, it could have ramifications for other industries. Agricultural drainage ditches could become more strictly regulated, as could coal ash ponds, which hold the waste from coal plants.“Industry worries that this would be a start toward regulating groundwater, And furthermore, it also could let people know the groundwater is largely unregulated,” Zygmunt Plater, an environmental law professor at Boston College told VICE News. “It is a small case that could have large analogies.”While industry may be worried about how this decision will affect their bottom lines, so is Maratea.“If the degradation of the reefs continues at the rate that it's going now, I definitely worry about the future of our business,” she said. Cover image: A sign warns of sewage contaminated ocean waters on a beach. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull)

Cover image: A sign warns of sewage contaminated ocean waters on a beach. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull)

Advertisement

“If the court were to adopt the position advocated by Maui County, then polluters could easily evade the act by just cutting their pipes short of the shoreline, or the river’s edge,” said David Henkin, an attorney with EarthJustice, who argued before the Supreme Court on behalf of the environmental groups. “This would create a huge regulatory loophole that’s never existed before.”“This would create a huge regulatory loophole that’s never existed before.”

Advertisement

Advertisement