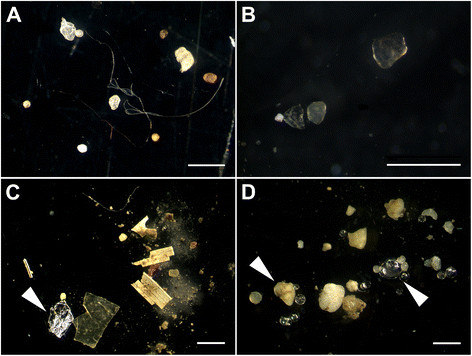

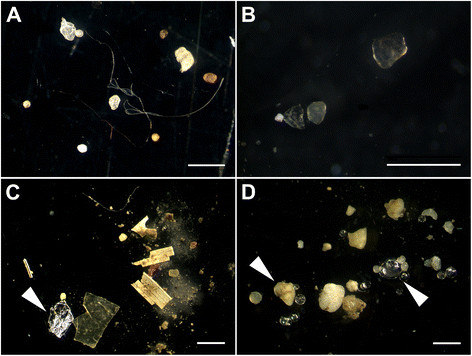

A new study published today in Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry highlights the need for a more comprehensive approach to studying the health effects of microplastics on animals and the environment.Microplastics are the nearly invisible pieces of plastic from consumer products that end up polluting the world’s rivers, oceans, lakes, and soil.They have become a major international political and environmental issue in the past few years that has resulted in legislation in the US, UK, and Japan that banned microplastics usually found in cosmetic products.The new paper is a meta-analysis of 320 studies on microplastics. It found “major knowledge gaps” in past microplastic research and concludes that current research is unclear about the environmental and health effects of microplastics. The study was funded by a major cosmetic industry trade group, which arguably has the biggest stake in changing microplastic legislation.“Based on our analysis there is currently limited evidence to suggest that microplastics are causing significant adverse impacts,” Alistair Boxall, an environmental scientist at the University of York and lead author of the study, said in a statement.A cursory Google search on microplastics, however, might lead you to think otherwise.Over the past few years, environmentalists and scientists have brought increasing scrutiny to microplastics. Dozens of scientific papers have demonstrated that microplastics are regularly ingested by many animals, including humans, which some researchers claim lead to adverse health effects. However the risks of microplastics to humans is still an emerging area of research that has been complicated by a recent high profile scandal involving fraudulent research about microplastic effects on human health.“If we are really going to understand impacts on the environment, we need to start testing the microplastic materials that actually occur in the environment,” Boxall told me.For example, researchers studying health effects tend to look at “nanoplastics,” or those that are between 1/1000 millimeter and 1/10,000 millimeter in size. These nanoplastics have greater chance of causing adverse health effects because they can penetrate cells and embed themselves in animal tissue. Studies focusing on the amount of microplastics in the environment, however, tend to look at larger microplastics that range from 5 mm to about 1/100 millimeter in size.“Monitoring for very small micro- to nanoplastics is inherently difficult given their small size and the complications of the environmental matrix (i.e., pieces of shel or sand being mistaken for plastic,” Sam Mason, a chemist at State University New York who was not involved in the study told me in an email. “We don’t have any high-throughput means for analyzing these small particles so at this point it is extremely time consuming and expensive.”Boxall and Burns also found that most microplastics studies tend to focus on fibers and fragments of plastic as opposed to beads, which only account for about 3 percent of the microplastics studied. Unlike fragments and fibers, which break off from clothes, rubber tires, condoms, and other products, beads tend to be added to a product purposely, such as beauty products that use them as exfoliants.“There is some evidence to suggest that if a microparticle has a sharp edge then it can affect organisms,” Boxall said. “Work from the nanoparticle field would suggest that toxicity will depend on a range of factors including the particle size, shape and material type, but I don’t think we yet have the understanding of how these different factors affect toxicity.” Moreover, in the past few years, research on microplastics has resulted in a regulatory crackdown on some products, particularly cosmetics. In 2015, the Obama administration enacted the Microbead-Free Waters Act that bans microplastic beads in cosmetic products like toothpaste or face wash. A similar law was passed last year in the UK and earlier this year in Japan.In other words, if anyone has an axe to grind when it comes to the regulation of microplastics, it’s the cosmetics industry.Boxall acknowledged that there is “certainly a risk that some people will perceive us as industry influenced,” but defended his research as a “balanced and evidenced-based analysis.”“When we were asked to perform the review, I made it quite clear that the conclusions had to be based on the scientific evidence and that PCPC could not influence the conclusions,” Boxall told me. “We are not saying that microplastics are not causing harm, but that based on the data it is not currently possible to conclude whether toxic impacts are happening or not.”Boxall said he hopes that the study helps steer research on microplastics in a direction that allows for the proper characterization of risks associated with microplastics so that effective regulation can be developed, a sentiment that was echoed by Mason.“All of us have been noting these issues the past few years and the issues noted are not uncommon in new emerging fields,” Mason told me. “Honestly, we need studies like these to help push the funding toward the projects that need to be done.”

Moreover, in the past few years, research on microplastics has resulted in a regulatory crackdown on some products, particularly cosmetics. In 2015, the Obama administration enacted the Microbead-Free Waters Act that bans microplastic beads in cosmetic products like toothpaste or face wash. A similar law was passed last year in the UK and earlier this year in Japan.In other words, if anyone has an axe to grind when it comes to the regulation of microplastics, it’s the cosmetics industry.Boxall acknowledged that there is “certainly a risk that some people will perceive us as industry influenced,” but defended his research as a “balanced and evidenced-based analysis.”“When we were asked to perform the review, I made it quite clear that the conclusions had to be based on the scientific evidence and that PCPC could not influence the conclusions,” Boxall told me. “We are not saying that microplastics are not causing harm, but that based on the data it is not currently possible to conclude whether toxic impacts are happening or not.”Boxall said he hopes that the study helps steer research on microplastics in a direction that allows for the proper characterization of risks associated with microplastics so that effective regulation can be developed, a sentiment that was echoed by Mason.“All of us have been noting these issues the past few years and the issues noted are not uncommon in new emerging fields,” Mason told me. “Honestly, we need studies like these to help push the funding toward the projects that need to be done.”

Advertisement

The new research by Boxall and his colleague Emily Burns, an environmental chemist at the University of York, highlighted the disparities between research that focuses on the health effects of microplastics and those that focus on the concentration of microplastics in the environment. Boxall said current research across these two focus areas was like comparing “apples and pears.”“We are not saying that microplastics are not causing harm, but that based on the data it is not currently possible to conclude whether toxic impacts are happening or not.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

According to Mason, the disparity between researchers studying microplastic concentrations in the environment and those studying toxicity is to be expected.“The smaller the particle the more likely it will be ingested and thus cause harm, so ecotoxicologists focus on these smaller particles,” Mason told me. “They use manmade particles in these size ranges that fluoresce, allowing for ease of detection. This is a luxury those of us who do environmental testing don’t have.”According to Boxall’s research, only focusing legislation on microbeads ignores the reality of the types and concentrations of microplastics in the environment. "We believe regulations and controls may be focusing on activities that are having limited impact and ignoring the most polluting activities such as releases of small particles from tyres on our cars,” Boxall said in a statement.While taking an evidence-based approach to microplastic regulation isn’t controversial, a point of concern with Boxall and Burns’ study is that it was funded by the Personal Care Products Council, a trade group representing the cosmetics industry. In the past, the PCPC has funneled hundreds of thousands of dollars into lobbying against legislation that required cosmetics companies to list harmful chemicals on their products.Read More: How We’ll Solve Our Plastic Problem

Advertisement