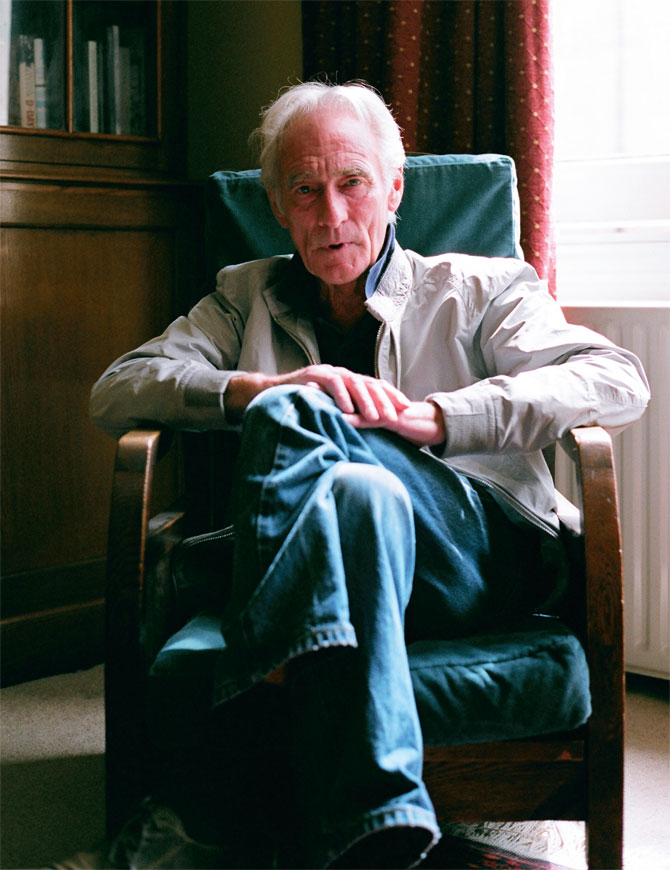

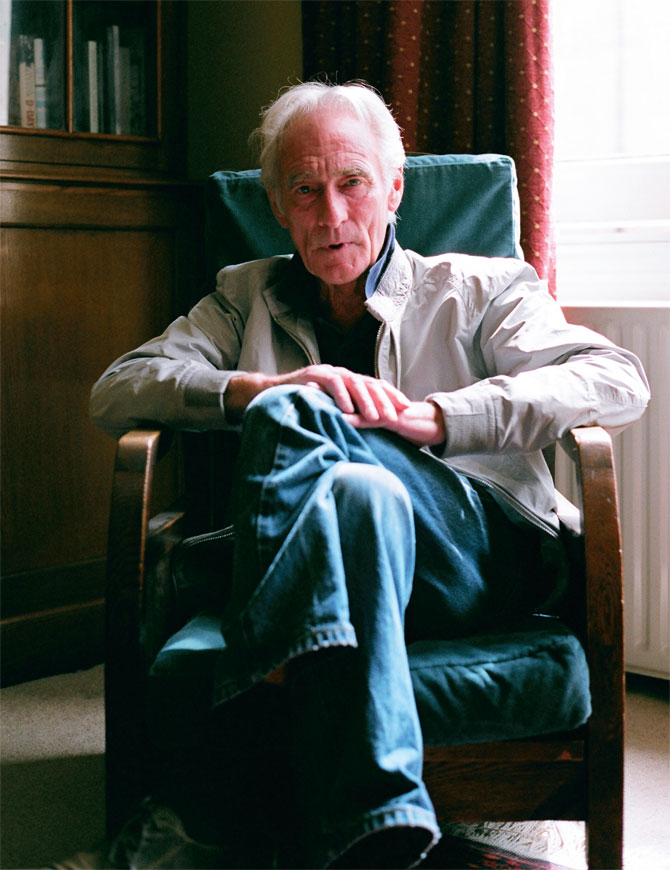

Interview By Alex MillerPhoto By Ben Rayner Jack Bond was a headmaster when he was 21. Sometime after that he lost a full-grown bear and nearly 50 mental patients in the woods in Wales. He also rolled with Warhol and Magritte in New York and drove Salvador Dali into a rage. These days, he’s making a film that the French intelligence services have warned him may cost him his life. His life is as unusual as his directorial career.British directors traditionally leave the art to the French while they dig under the kitchen sinks of Britain’s crumbling societies, but director Jack Bond, together with writer and actor Jane Arden, created a canon of avant-garde, paranoid films which, while celebrated in America, have been largely lost from British cinematic history.In 1965, Bond, then 28, and Arden spent two weeks with Salvador Dali filming the dramatic documentary Dali in New York. Until Arden killed herself in 1982, the pair worked together on a series of dense, obscure, psychedelic films:Separation(1967),The Other Side of the Underneath(1972),Vibration(1975), andAnti-Clock(1979). After being unseen for over 20 years, the BFI are re-releasing them this year on DVD.Anti-Clockis their greatest achievement. It’s a surreal Oedipal thriller set both in a hotel full of CCTV and mad therapists, and inside the abused mind of volatile murderer they are studying. It’s close in premise toA Clockwork Orange, but far more intense, bizarre, and devastating. It’s weird, then, that Jack’s about the coolest, most convivial 71-year-old living in Bloomsbury today.Vice: Why have the films you made with Jane Arden remained hidden for so long?Jack Bond:When Jane Arden committed suicide, it had such a violent effect on me that I put them away. I stored them away in a laboratory in the national film archive with orders on them that they weren’t to be shown again or ever released. Strange reaction, isn’t it? I find it hard to work out why I did that.So you hadn’t seen them since 1982?No. After a memorial screening for Jane Arden at the National Film Centre that year, they were never seen. When I finally rang up the archive they said, “No, no, no, no. That stuff’s not to leave here, every can’s got a label on it: ‘Never to be released again by order of Jack Bond’.” I said, “Wait a minute, I am Jack Bond!” So I had to go down with my passport and driver’s licence.Anti-Clock was actually never released in the UK at all. Why was that?Well, in America the support we had was incredible, it won a Golden Globe, and it ran well in decent cinemas. Then I came back to England, showed it to a few distributors and got incredibly negative feedback. At that point I said to Jane, “Fuck England, I’m not going to show it here.” And she said, “Fine, let’s do that.” So we didn’t show it here. A couple of years later they’re ringing me up and asking for it, but we said no. That was the beauty of Jane, she was completely supportive of my rather uncommercial attitude. And we had other interests in life. I had a bloody great yacht, and I set off on it for three years.Separation was banned from the Cork Film Festival, Anti-Clock was rejected over here—did you feel like you were making controversial art-house films?The truth is I was a foolish optimist. I couldn’t, in my mind, separate mainstream from more off-beat stuff, and when I was making all these films I couldn’t see any other way of doing them. And it didn’t seem in the least bit odd to me really. [French director] Louis Malle once pointed it out to me: “Quite simply, Jack, you were born in the wrong country. I don’t know who you are, but you don’t seem very English to me. I can’t see you surviving in England. If your work was French, nobody would think anything about it, but you’ve got nobody to play with there.”Somewhere in Anti-Clock’s unsettling mix of the past, madness, premonition, demon psychology and occult philosophy, you managed to make a film which predicted the visual language of surveillance society. Did you see that coming?I went to Sony and explained that what I was doing was establishing CCTV. It’s a film about a man with a very self-destructive nature, who is either going to kill someone or kill himself, who goes to a hotel for a weekend enlightenment course. I wanted the guy to be observed on CCTV so he couldn’t walk up a staircase or go in a room without being followed by cameras. Sony loved this idea, maybe they saw the future, but I don’t think I was seeing it in those terms, I had no idea it’d be like this now. Sony took my idea very seriously. They festooned the roof of the hotel with cameras so the streets were surveyed, as well as the interior of the hotel.Warhol was a big fan. Did you know him?Yes, for years. Dali introduced us when we were makingDali in New York. He took me and Warhol to the opening night of René Magritte’s retrospective.That’s a big line-up.Yeah. We got in a cab and Dali said to me, “I rang René Magritte this afternoon and I told him we were coming and I asked him if we could arrive with pineapples on our heads”. Apparently Magritte said to him, “If you choose to come here looking ridiculous, you will not be allowed in!” How amazing, one surrealist telling another not to look ridiculous! When we got there, there was René Magritte in a three-piece pinstripe suit with a watch chain. He looked for all the world like a bank manager.In Dali in New York, Dali seems pretty intense.Oh God, yes. I saw him not that long ago in New York and I asked him at what point in his life did he realise who he was? He told me it happened when he was 12. He was out for a walk with a particularly beautiful, glamorous auntie, who suddenly wanted to piss. She stood up, pulled her skirt up and pissed with the force of a carthorse. He said the amber liquid struck the ground with such violence that it exploded into a million tiny droplets backlit by the sun, and all these droplets were suffused with divine knowledge. And that’s the moment he realised. Isn’t that fantastic?During the filming of Dali in New York, he famously stormed off set when Jane Arber stood up to him.He did! He was sitting on the side of the street and he holds out his wrist and says, “And now you will do up my cufflinks, please.” So Jane does one cufflink and and he says, “Now you are my slave.” She said, “Oh no, no, no. I’m perfectly happy to do up your cufflinks my darling, but in no way am I your slave or anyone else’s.” “You are my slave,” he says and he stands up and shouts, “Everybody is my slave!” And he goes off down with his flunky getting bits of dust off his coat, shouting, “Everybody is my slave!” We thought that was it for the film. I mean, he fucked off completely. And I thought, oh bloody hell, we’re only two days in and he’s gone, he’s not coming back. So I rang Andy [Warhol] and I said “He’s buggered off!” and he suggested we made a film together. I had this wonderful crew, so I said, “Well, have you got any ideas, because I haven’t.” He wanted to make a film in a sweet factory in Brooklyn, and he wanted it to run for 36 hours. That night Dali’s manager rang me up and saidDali in New Yorkwas on again.So you never got to make the Warhol movie?No!

Jack Bond was a headmaster when he was 21. Sometime after that he lost a full-grown bear and nearly 50 mental patients in the woods in Wales. He also rolled with Warhol and Magritte in New York and drove Salvador Dali into a rage. These days, he’s making a film that the French intelligence services have warned him may cost him his life. His life is as unusual as his directorial career.British directors traditionally leave the art to the French while they dig under the kitchen sinks of Britain’s crumbling societies, but director Jack Bond, together with writer and actor Jane Arden, created a canon of avant-garde, paranoid films which, while celebrated in America, have been largely lost from British cinematic history.In 1965, Bond, then 28, and Arden spent two weeks with Salvador Dali filming the dramatic documentary Dali in New York. Until Arden killed herself in 1982, the pair worked together on a series of dense, obscure, psychedelic films:Separation(1967),The Other Side of the Underneath(1972),Vibration(1975), andAnti-Clock(1979). After being unseen for over 20 years, the BFI are re-releasing them this year on DVD.Anti-Clockis their greatest achievement. It’s a surreal Oedipal thriller set both in a hotel full of CCTV and mad therapists, and inside the abused mind of volatile murderer they are studying. It’s close in premise toA Clockwork Orange, but far more intense, bizarre, and devastating. It’s weird, then, that Jack’s about the coolest, most convivial 71-year-old living in Bloomsbury today.Vice: Why have the films you made with Jane Arden remained hidden for so long?Jack Bond:When Jane Arden committed suicide, it had such a violent effect on me that I put them away. I stored them away in a laboratory in the national film archive with orders on them that they weren’t to be shown again or ever released. Strange reaction, isn’t it? I find it hard to work out why I did that.So you hadn’t seen them since 1982?No. After a memorial screening for Jane Arden at the National Film Centre that year, they were never seen. When I finally rang up the archive they said, “No, no, no, no. That stuff’s not to leave here, every can’s got a label on it: ‘Never to be released again by order of Jack Bond’.” I said, “Wait a minute, I am Jack Bond!” So I had to go down with my passport and driver’s licence.Anti-Clock was actually never released in the UK at all. Why was that?Well, in America the support we had was incredible, it won a Golden Globe, and it ran well in decent cinemas. Then I came back to England, showed it to a few distributors and got incredibly negative feedback. At that point I said to Jane, “Fuck England, I’m not going to show it here.” And she said, “Fine, let’s do that.” So we didn’t show it here. A couple of years later they’re ringing me up and asking for it, but we said no. That was the beauty of Jane, she was completely supportive of my rather uncommercial attitude. And we had other interests in life. I had a bloody great yacht, and I set off on it for three years.Separation was banned from the Cork Film Festival, Anti-Clock was rejected over here—did you feel like you were making controversial art-house films?The truth is I was a foolish optimist. I couldn’t, in my mind, separate mainstream from more off-beat stuff, and when I was making all these films I couldn’t see any other way of doing them. And it didn’t seem in the least bit odd to me really. [French director] Louis Malle once pointed it out to me: “Quite simply, Jack, you were born in the wrong country. I don’t know who you are, but you don’t seem very English to me. I can’t see you surviving in England. If your work was French, nobody would think anything about it, but you’ve got nobody to play with there.”Somewhere in Anti-Clock’s unsettling mix of the past, madness, premonition, demon psychology and occult philosophy, you managed to make a film which predicted the visual language of surveillance society. Did you see that coming?I went to Sony and explained that what I was doing was establishing CCTV. It’s a film about a man with a very self-destructive nature, who is either going to kill someone or kill himself, who goes to a hotel for a weekend enlightenment course. I wanted the guy to be observed on CCTV so he couldn’t walk up a staircase or go in a room without being followed by cameras. Sony loved this idea, maybe they saw the future, but I don’t think I was seeing it in those terms, I had no idea it’d be like this now. Sony took my idea very seriously. They festooned the roof of the hotel with cameras so the streets were surveyed, as well as the interior of the hotel.Warhol was a big fan. Did you know him?Yes, for years. Dali introduced us when we were makingDali in New York. He took me and Warhol to the opening night of René Magritte’s retrospective.That’s a big line-up.Yeah. We got in a cab and Dali said to me, “I rang René Magritte this afternoon and I told him we were coming and I asked him if we could arrive with pineapples on our heads”. Apparently Magritte said to him, “If you choose to come here looking ridiculous, you will not be allowed in!” How amazing, one surrealist telling another not to look ridiculous! When we got there, there was René Magritte in a three-piece pinstripe suit with a watch chain. He looked for all the world like a bank manager.In Dali in New York, Dali seems pretty intense.Oh God, yes. I saw him not that long ago in New York and I asked him at what point in his life did he realise who he was? He told me it happened when he was 12. He was out for a walk with a particularly beautiful, glamorous auntie, who suddenly wanted to piss. She stood up, pulled her skirt up and pissed with the force of a carthorse. He said the amber liquid struck the ground with such violence that it exploded into a million tiny droplets backlit by the sun, and all these droplets were suffused with divine knowledge. And that’s the moment he realised. Isn’t that fantastic?During the filming of Dali in New York, he famously stormed off set when Jane Arber stood up to him.He did! He was sitting on the side of the street and he holds out his wrist and says, “And now you will do up my cufflinks, please.” So Jane does one cufflink and and he says, “Now you are my slave.” She said, “Oh no, no, no. I’m perfectly happy to do up your cufflinks my darling, but in no way am I your slave or anyone else’s.” “You are my slave,” he says and he stands up and shouts, “Everybody is my slave!” And he goes off down with his flunky getting bits of dust off his coat, shouting, “Everybody is my slave!” We thought that was it for the film. I mean, he fucked off completely. And I thought, oh bloody hell, we’re only two days in and he’s gone, he’s not coming back. So I rang Andy [Warhol] and I said “He’s buggered off!” and he suggested we made a film together. I had this wonderful crew, so I said, “Well, have you got any ideas, because I haven’t.” He wanted to make a film in a sweet factory in Brooklyn, and he wanted it to run for 36 hours. That night Dali’s manager rang me up and saidDali in New Yorkwas on again.So you never got to make the Warhol movie?No! From left: Anti-Clock (1979), Separation (1967), and The Other Side of the Underneath (1972)You were in the army, right?Yes, I had to do national service for two years. The first three months basic training with the Green Howards was very tough for a spoilt rich boy with an arty bent. After that they said they were going to send me to Sandhurst to learn to become an officer. I had a problem with that because my dad was a senior officer and I didn’t want to follow him. So, they sent me to Beaconsfield Royal Army Education Corps.And you became a teacher?Yes, they sent me to Hong Kong, and I ended up being the headmaster of a school when I was 21 with 11 teachers below me who were between the ages of 27 and 55. I was terrified, thought they’d kill me. On the first day I lined all the teachers up and said, “OK, you’re not going to like this. I’m headmaster from today. But you will knuckle down and work with me or you can leave now. Anybody who’s not up for it, there’s the door—go.” I was petrified, but nobody left, it worked, and I had a lovely time.After that, it was at the BBC that you got your first directing experience, right?Yes, me and my mate were givenPoints of View.We had to produce three editions a week. I brought Spike Milligan in to present the children’s edition. He did a few episodes and then it all fell apart. The problem was the letters we received for the show were dreadful, so we started writing them ourselves.Ha ha. Did they find you out?Well, the letters we were writing were frighteningly savage and the BBC programmes we were slamming were complaining about these vicious attacks. I was called into [programme controller] Huw Wheldon’s office, and Huw says, “Can we talk about Mrs fucking Ann Taylor, you cunt, from Bristol fucking Temple Meads! We know it’s you and you’ll be clearing your desk by midday.” And I did. I got a job driving an HGV. Carrying lots of electrical cabling, stuff like that.So when did you actually start directing?Well, six weeks later Huw’s secretary called me, I went in to see him, he gave me the complete works of Wilfred Owen and said, “You are going to make a film about the First World War seen through the eyes of Wilfred Owen who died the week before armistice. Have you checked your bank account recently?” They had never stopped paying me. I madeThe Pity of War, and that’s how I became a film director. I still think that was maybe the best thing I ever made. I was 24.What are you working on at the moment?Right now I’m preparing and researching a World War Two film calledEarly One Morning. It concerns the fate of two racing drivers, one Frenchman and one Brit, who became spies and were both caught. We know the French guy was hanged but there was lot of mystery about the English guy: was he really an agent, in a sense maybe a double agent? We are sure that the concentration camps these two guys were in were being supplied with Zyklon B for gassing prisoners by a French factory only 75 kilometres from Paris. No one ever got prosecuted for it. There was one guy who was the managing director of the company, who protested, refused to do it. They kicked him out of his house and sent him and his wife to a concentration camp where they were eventually exterminated by the same stuff that was being exported from his old factory.We proved it, and this fucking company still exists, on the same site. No one ever got prosecuted for it. I also believe the railways, the SNCF, knew what they were shipping as well. I’ve seen the way-loading bills which showed that they knew what they were doing.It sounds like dangerous information.Yes, I changed the company name on the advice of the French intelligence service. There was a French journalist who’d been digging into the same story and suddenly he was gone without a trace. But when we make the film, it’ll be there.Is it true that while making The Other Side of the Underneath, a bear and a bunch of mental patients escaped from the shoot?Well, Jane decided she wanted a bear for the film, so I rang Harrods and they said, “Well, we can get you a bear, when do you need it?” So they put it on the train in a wooden crate on a train to Newport station where we were filming. We’d prepared a stable with lots of straw, but when we let it out it attacked us all. About six of us had to go to the hospital and explain that we’d been attacked by a bear. They thought it was all bullshit. Eventually they found out it was the truth when the bear escaped. It was finally captured three days later when it was caught smashing milk bottles on people’s doorsteps. It was all in the papers: “Bear smashing milk bottles in Nantygroes!”Ha ha. What about the mental patients?That was worse. Jane wanted real inmates of a real asylum that was down the road for a party scene. So I went down to do the talking. “How can you maintain security?” they asked. I said I’d hire a 52-seat coach, it will be accompanied by a transit van in front and a transit van behind. There’ll be plenty of people, and it’s probable that your inmates will have a nice day out at this party we’re going to throw. So she let us have about 44 people.It probably went wrong when someone brought a hash cake. When we tried to return them to the asylum, they didn’t want to go. They’d tasted this strange freedom with all these other people who were being very nice to them, and so getting them back in the coach was a nightmare. Finally they were loaded up and the doors shut but it’s now late, I’m supposed to have them back by 5:30 PM, but it’s now dark, it’s night. I’m following from behind, but then my van got a puncture. We changed it as quickly as we could and went chasing after this coach. We come sweeping round the bend and there it is, the coach, like something out of theRepo Man, it’s stood there with all of its lights on, but completely empty.Finally I found the driver sitting on a rock. “They’ve all legged it,” he said. “They wanted to pee, and I didn’t think.” So the police were called again, it took days to round them up with only a few scratches and bruises. Of course, I had to go and see the woman from the hospital to tell her what happened. She looked at me sternly and said, “Mr Bond, I think you are the most irresponsible man on the face of God’s earth.”Ha ha. Maybe she had a point.Maybe.Jane Arden and Jack Bond’sSeparation, The Other Side of the UnderneathandAnti-Clockare out now for the first time on DVD & Blu-ray from the BFI.

From left: Anti-Clock (1979), Separation (1967), and The Other Side of the Underneath (1972)You were in the army, right?Yes, I had to do national service for two years. The first three months basic training with the Green Howards was very tough for a spoilt rich boy with an arty bent. After that they said they were going to send me to Sandhurst to learn to become an officer. I had a problem with that because my dad was a senior officer and I didn’t want to follow him. So, they sent me to Beaconsfield Royal Army Education Corps.And you became a teacher?Yes, they sent me to Hong Kong, and I ended up being the headmaster of a school when I was 21 with 11 teachers below me who were between the ages of 27 and 55. I was terrified, thought they’d kill me. On the first day I lined all the teachers up and said, “OK, you’re not going to like this. I’m headmaster from today. But you will knuckle down and work with me or you can leave now. Anybody who’s not up for it, there’s the door—go.” I was petrified, but nobody left, it worked, and I had a lovely time.After that, it was at the BBC that you got your first directing experience, right?Yes, me and my mate were givenPoints of View.We had to produce three editions a week. I brought Spike Milligan in to present the children’s edition. He did a few episodes and then it all fell apart. The problem was the letters we received for the show were dreadful, so we started writing them ourselves.Ha ha. Did they find you out?Well, the letters we were writing were frighteningly savage and the BBC programmes we were slamming were complaining about these vicious attacks. I was called into [programme controller] Huw Wheldon’s office, and Huw says, “Can we talk about Mrs fucking Ann Taylor, you cunt, from Bristol fucking Temple Meads! We know it’s you and you’ll be clearing your desk by midday.” And I did. I got a job driving an HGV. Carrying lots of electrical cabling, stuff like that.So when did you actually start directing?Well, six weeks later Huw’s secretary called me, I went in to see him, he gave me the complete works of Wilfred Owen and said, “You are going to make a film about the First World War seen through the eyes of Wilfred Owen who died the week before armistice. Have you checked your bank account recently?” They had never stopped paying me. I madeThe Pity of War, and that’s how I became a film director. I still think that was maybe the best thing I ever made. I was 24.What are you working on at the moment?Right now I’m preparing and researching a World War Two film calledEarly One Morning. It concerns the fate of two racing drivers, one Frenchman and one Brit, who became spies and were both caught. We know the French guy was hanged but there was lot of mystery about the English guy: was he really an agent, in a sense maybe a double agent? We are sure that the concentration camps these two guys were in were being supplied with Zyklon B for gassing prisoners by a French factory only 75 kilometres from Paris. No one ever got prosecuted for it. There was one guy who was the managing director of the company, who protested, refused to do it. They kicked him out of his house and sent him and his wife to a concentration camp where they were eventually exterminated by the same stuff that was being exported from his old factory.We proved it, and this fucking company still exists, on the same site. No one ever got prosecuted for it. I also believe the railways, the SNCF, knew what they were shipping as well. I’ve seen the way-loading bills which showed that they knew what they were doing.It sounds like dangerous information.Yes, I changed the company name on the advice of the French intelligence service. There was a French journalist who’d been digging into the same story and suddenly he was gone without a trace. But when we make the film, it’ll be there.Is it true that while making The Other Side of the Underneath, a bear and a bunch of mental patients escaped from the shoot?Well, Jane decided she wanted a bear for the film, so I rang Harrods and they said, “Well, we can get you a bear, when do you need it?” So they put it on the train in a wooden crate on a train to Newport station where we were filming. We’d prepared a stable with lots of straw, but when we let it out it attacked us all. About six of us had to go to the hospital and explain that we’d been attacked by a bear. They thought it was all bullshit. Eventually they found out it was the truth when the bear escaped. It was finally captured three days later when it was caught smashing milk bottles on people’s doorsteps. It was all in the papers: “Bear smashing milk bottles in Nantygroes!”Ha ha. What about the mental patients?That was worse. Jane wanted real inmates of a real asylum that was down the road for a party scene. So I went down to do the talking. “How can you maintain security?” they asked. I said I’d hire a 52-seat coach, it will be accompanied by a transit van in front and a transit van behind. There’ll be plenty of people, and it’s probable that your inmates will have a nice day out at this party we’re going to throw. So she let us have about 44 people.It probably went wrong when someone brought a hash cake. When we tried to return them to the asylum, they didn’t want to go. They’d tasted this strange freedom with all these other people who were being very nice to them, and so getting them back in the coach was a nightmare. Finally they were loaded up and the doors shut but it’s now late, I’m supposed to have them back by 5:30 PM, but it’s now dark, it’s night. I’m following from behind, but then my van got a puncture. We changed it as quickly as we could and went chasing after this coach. We come sweeping round the bend and there it is, the coach, like something out of theRepo Man, it’s stood there with all of its lights on, but completely empty.Finally I found the driver sitting on a rock. “They’ve all legged it,” he said. “They wanted to pee, and I didn’t think.” So the police were called again, it took days to round them up with only a few scratches and bruises. Of course, I had to go and see the woman from the hospital to tell her what happened. She looked at me sternly and said, “Mr Bond, I think you are the most irresponsible man on the face of God’s earth.”Ha ha. Maybe she had a point.Maybe.Jane Arden and Jack Bond’sSeparation, The Other Side of the UnderneathandAnti-Clockare out now for the first time on DVD & Blu-ray from the BFI.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement