If there is anything that film has taught us about female-presenting robots, it’s that they’re stacked. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) is the first cinema representation of the fembot (or gynoid), a golden-plated humanoid, who, one can’t help noticing, has metallic round breasts. Two chrome domes.The ridiculousness of the robot titties was obviously not lost on the designers, who circled the breasts of the robot with an art deco-inspired ring, as if to symbolize that this part was not an essential component but a decorative one. Decorative objects, Jacques Derrida noted in his analysis of Immanuel Kant’s aesthetics in The Parergon, are theoretically not part of the object; the decorative is there only for our pleasure, while, at the same time, by framing the object, the decorative defines its essence. Just as certain domestic appliances, from hair dryers to headphones, have aerodynamic decoration to indicate their closeness to air and wind despite not moving at all, the round bosoms of the fembot define the robot as female despite having no function for the machine.

Advertisement

Of course, with fembots, feminization may begin with the titty, but it doesn’t end with the titty. Decoration is the go-to method to express the idea of a gendered machine, and the female robot is decorated with long, fake lashes and curves that are sinuous and pleasing. Sometimes fembots wear clothing, and their sartorial choices tend to read “retro,” with ’50s-inspired dresses or skirts and heels (think The Stepford Wives, Ex Machina, Rachel from Blade Runner, and Dot Matrix’s chrome skirt in Spaceballs).

Even when a fembot has no explicit sexual function, like the crude coffee-serving robot named “Sweetheart” made by American sculptor Clayton Bailey, the robot tits are there, out to here, defined in such an exaggerated way that we almost dissociate the robots tits from reality. The breast loses its function of nutrition and connection with the child, as well as its softness. Here, the breast stands for itself, as a pleasurable characteristic for someone else, someone who is a human and not even a robot, completely separated from any of the reasons it has developed in our biology. When a controversy emerged around Sweetheart, Clayton’s defense was, “This is my idea of what a pretty female robot should look like.”

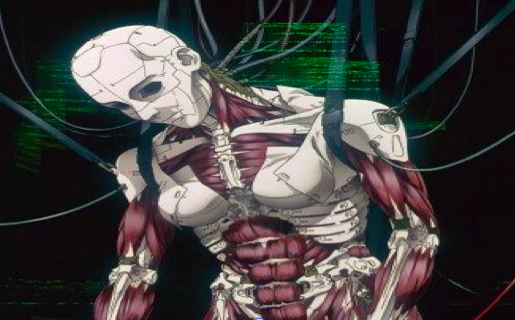

In robots, gender achieves complete autonomy from its reproductive function, queered into being geared only toward pleasure. Almost like a metaphor for gay sex itself, robots imitate and exhibit sexual traits that only elicit pleasure in someone else or themselves. Like furries, they imitate sexual traits that don’t belong to their kind. With the queer and trans community, robots in media often share the burden of “passing.” In Ghost in the Shell, the main character, Motoko Kusanagi, who has a human brain but has lived in cybernetic shells all her life, decides to endow her body with a boob job, both out of vanity and because she has a lucrative side hustle to her military career as a lesbian sex worker for other enhanced humans. Naturally, the opening sequence of the 1997 Ghost in the Shell anime features a montage of the naked robot as her human body is formed in the lab, the breasts are lingered over, shown to be metallic and painted on with artificial skin.

Advertisement

In these films, the more feminine the fembot, the more rogue she might go. As with the femme fatale, the gynoid’s sexuality is unruly and dangerous and subject to the rules of capital. Robots, like the “best” workers, are completely dedicated to their task. But also like workers, when they are too smart they can’t be trusted, we fear that they might overthrow their rulers. The trickery and seduction of their sexual appeal, according to puritan reads, conceals a danger. The breast now only functions to attract our attention, to distract us, and, from there, Austin Powers’s fembots’ machine guns emerge to kills us.

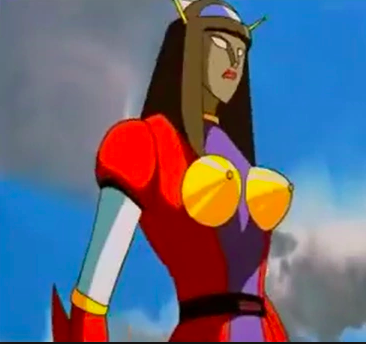

In Go Nagai’s Venus (featuring a giant alien fighting robot), the tits are, in reality, rockets that the main character shoots at enemies. In his In a Queer Time and Place, Jack Halberstam explains how these robots show how femininity is not natural but often artificial. Hair extensions, lash extensions, breast implants, fake nails, makeup, injections: femininity itself is the product of an automated industry.

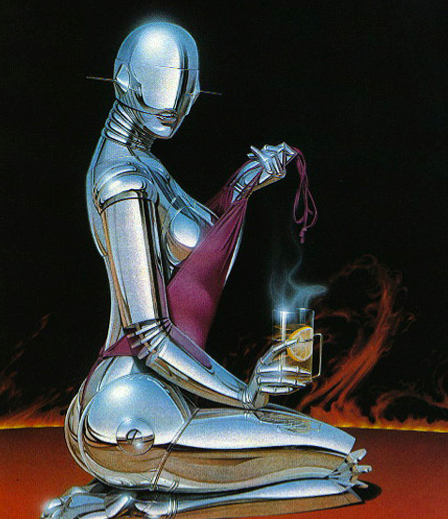

But in Hajime Sorayama’s paintings of chrome pinups, the separation of femininity from nature is represented as a positive fact. The chrome breasts in his pictures flatten as the models lay down or sag as the robot bends over naturally, as if the metal were as soft as flesh. Sorayama explained that his fascination with pinups was in part due to the fact that they were not girls next door—they were alien to him, a distant ideal that made them “like goddesses.”

Robots’ breasts don’t have to contain milk because robots don’t have to have children, and they don’t have to have children because they cannot die. Like gods, their true existence is not in their physical form but in the blueprint from which each copy is created. In Metropolis, the gynoid was created as a way to repair the trauma of losing a loved woman; the chrome goddesses are the promise of a femininity without separation, of a flesh that is both as resistant and shiny as a metal but as sensitive to touch and soft as our own skin. They are the promise of beauty and pleasure without end, if not for free, at least for a convenient price.