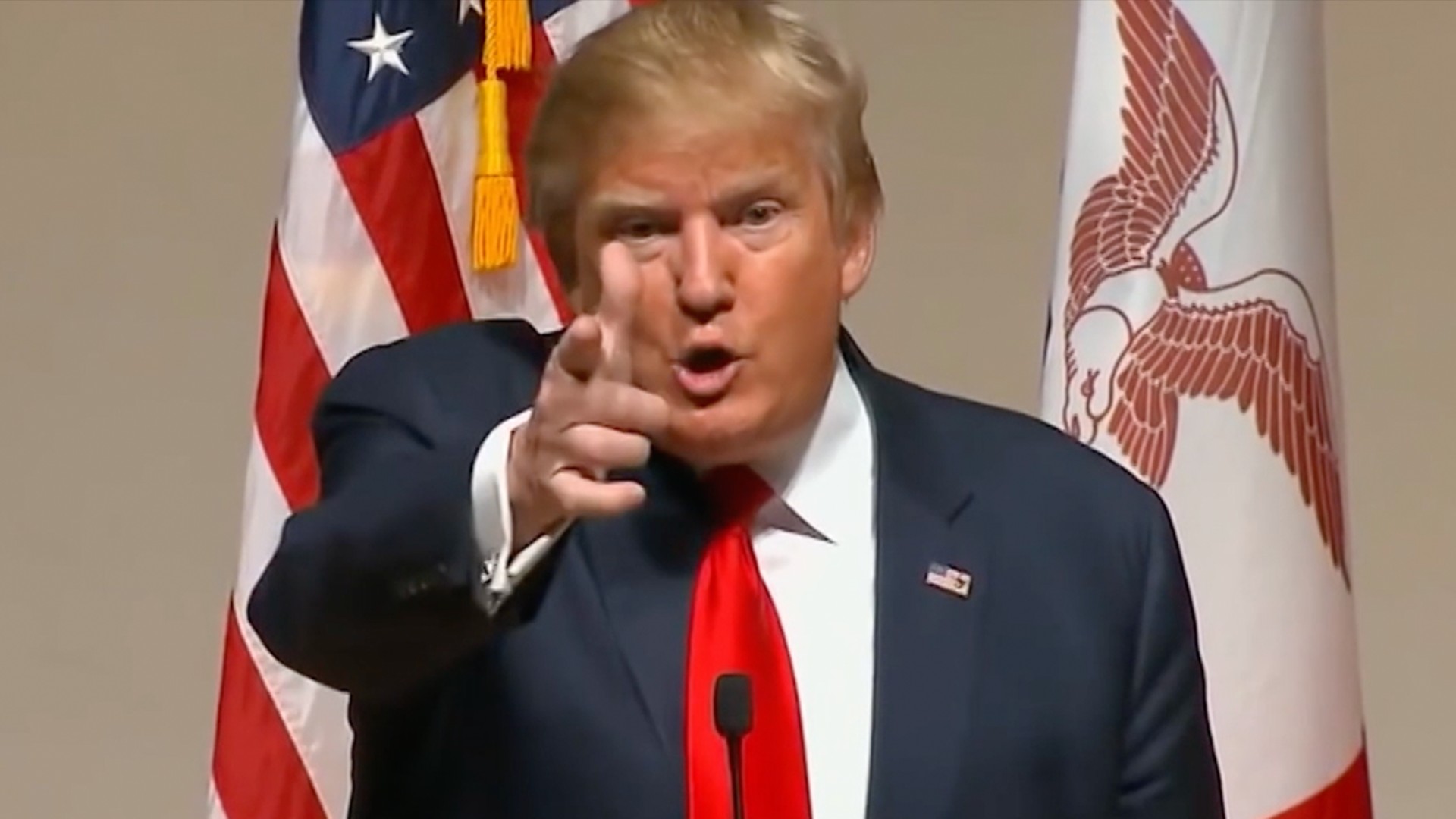

An 'active shooter' attacks a classroom during ALICE (Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter and Evacuate) training at the Harry S. Truman High School in Levittown, Pennsylvania, on November 3, 2015. Photo by Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images

You know it's 2017 when the same school-safety officer who teaches Las Vegas kindergarteners how to survive an armed attack has three cellphones in front of him to help respond to the worst mass shooting in modern American history.Roy Anderson couldn't talk for very long when I reached him by phone near the site at which 59 people were killed and 527 wounded earlier this week. But Captain Ken Young, spokesman for the Clark County School District Police, said their safety lessons—which emphasize situational awareness basics like taking note of potential exits—aren't all that different from what's taught in other large cities like Los Angeles or Miami. Which isn't surprising on its own until you consider that children in Alaska learn something almost diametrically opposed."This is a life skill, and where do we teach most life skills? They begin in school," said Greg Crane, founder and CEO of ALICE (Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, and Evacuate), a rival safety method he said has been taught in thousands of schools serving about a quarter of American students, including many in Alaska.In the 2013–14 academic year, more than two-thirds of public schools taught kids as young as four about what to do when confronted by a gunman, up from less than half a decade earlier. Gun dealers help teach courses at police summer camps, the Boy Scouts of America encourage active-shooter prep as part of its Emergency Preparedness merit badge, and at Girl Scout camp, the training counts toward earning a Safety Award."We've worked with every demographic, from daycares to YMCAs to Fortune 500s to hospitals," Crane, a former SWAT team leader, told me.

But a report published last year by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) found there are still no consistent federal guidelines as to which instructions actually work—or how kids should practice these skills. The difference between huddling in the nap corner and hurling Lincoln Logs at an intruder is roughly the difference between handing out condoms and telling kids they don't work, according to safety experts canvassed by VICE. And just like with sex ed, there is no national mandate for an evidence-based mass shooting prep curriculum."Now you can't start too young," said Julia Cook, the author of I'm Not Scared, I'm Prepared, a picture book for preschool and kindergarteners about how to escape a 'dangerous someone' at school. "It's not hard to extrapolate to what to do if you're at a mall," she added of the ALICE method, which is espoused in the book. "Even if they're three or four, you just have to have a plan."Cook's book instructs young children to arm themselves with blocks and plastic animals, and to sprint from the classroom to a safe spot outside when an adult gives the signal. But that's just the opposite of the tight, whimpering scrum University of Toledo education professor Dr. Katherine Delaney saw in traditional lockdown drills during her dissertation work in a Midwestern kindergarten."That's just not going to work," Delaney told me of the ALICE method. "As someone who's a former teacher of four-year-olds and now teaches people how to teach four-year-olds, it would be hard for me to imagine a scenario where I would shout at children, 'Run!' and they would understand, 'Run and hide someplace spread out from one another to protect yourselves from someone who wants to harm you.'"Michael Dorn, executive director of the campus safety company Safe Havens International—and not the Star Trek actor—was even more blunt. "We have 100 years of fire-science research to tell us that when people in large numbers run, they die," said the former cop, who teaches what he characterized as a more dynamic model of active-shooter prep in schools, including the Clark County district in Vegas.Dorn sees the federally-endorsed Run, Hide, Fight mantra—which has some overlap with but is not the same thing as ALICE, and is not intended for use in schools—as not only dangerous but, in cases like Las Vegas, essentially futile. (He's not the only critic.)"Running wasn't very helpful," he told me of attempts to escape the Vegas shooting. "Hiding—most people weren't in a position to hide. And fight, even if you'd had a Glock pistol and two magazines you couldn't have stopped him."Crane, the ALICE founder, insisted more people might have survived the Harvest Festival shooting if they'd run instead of cowering in the grass. He added he's got "no tolerance" for anyone who says even small children can't safely do the same. "It's not theoretical. They did do it," he said.There is precious little statistical evidence out there about which method—whether ALICE, Dorn's more general approach, or some other one—might be most effective. As the Atlantic reported, a 2014 Police Executive Research Forum analysis of 84 incidents between 2000 and 2010 described shooters targeting people who "froze in place or attempted to play dead." That seems like evidence in support of ALICE's more proactive approach, or perhaps the FBI's "Avoid, Deny, Defend" slogan born out of the Advanced Law Enforcement and Rapid Response Training Center (ALERRT) at Texas State University in 2013."We're not a big fan of the word 'hide' at ALERRT because it's passive," Pete Blair, the professor who oversees the center, told the Atlantic in 2015. "What do you do if the active shooter occurs during the school assembly? Or in the cafeteria? What are people in the room where the attack starts supposed to do?"Dorn, for his part, argued many people come out of Run, Hide, Fight–style programs less prepared to handle a mass shooting than those with no training at all (a statement Crane called "the most ridiculous thing I've ever heard.") "Since the Sandy Hook attack, there have been an array of very emotive programs that have never been tested," Dorn insisted. "There's about a dozen of them, and we get the same results with all of them," during practice scenarios, when a math teacher is more likely to charge a suicidal student with a gun to his head than to try to comfort him, he said.His position makes Dorn among the most outspoken opponents of popular programs like ALICE, which he regards as particularly ill-suited to children. "We've had some really bad instances, up to the extent of a police officer walking up to students with a real gun loaded with blanks and shooting them, saying 'You're dead," he told me. "We have seen police come in and teach kindergarten kids, 'You're going to die cowering in a corner.' Where we've seen the most problems is when we teach really young children [to] throw a book at a gunman."And yet that's exactly what ALICE-trained teachers reading I'm Not Scared, I'm Prepared are instructing children to do. "Though student involvement in the option of fighting is not included in the Federal Guide, the FBI does not take a position on whether or not school districts should teach children to consider the option of fighting," the GAO noted in its 2016 report. (The Department of Education did not respond to a request for comment for this story, and the Department of Homeland Security did not comment beyond passing along resources on active-shooter prep.)Faced with worst-ever shootings as frequent as "hundred-year" storms and with no hope of meaningful gun control reform, teaching unarmed six-year-olds to fight adult men with automatic weapons might seem depressingly futile right now. But Dorn told me there are safe, proven, and lifesaving tools America can—but too often isn't—teaching those kids."Before we spend two days teaching someone how to take a gun away from somebody, let's look at the two-hour Stop the Bleed program," which teaches tourniquet techniques as a part of first aid, he offered. 'We wouldn't recommend teaching that to kindergarten children—but you could teach it in middle school."That distinction gets at the more existential matter simmering beneath the debate over how best to train kids to respond to mass shootings: When it comes to, say, third-graders, how much prep is reasonable?"I don't know the answer to that," Delaney, the education professor, told me when I asked how far we can push children to train for survival. "I think it's a really important question we need to start thinking about."Follow Sonja Sharp on Twitter.

Advertisement

But a report published last year by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) found there are still no consistent federal guidelines as to which instructions actually work—or how kids should practice these skills. The difference between huddling in the nap corner and hurling Lincoln Logs at an intruder is roughly the difference between handing out condoms and telling kids they don't work, according to safety experts canvassed by VICE. And just like with sex ed, there is no national mandate for an evidence-based mass shooting prep curriculum.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement