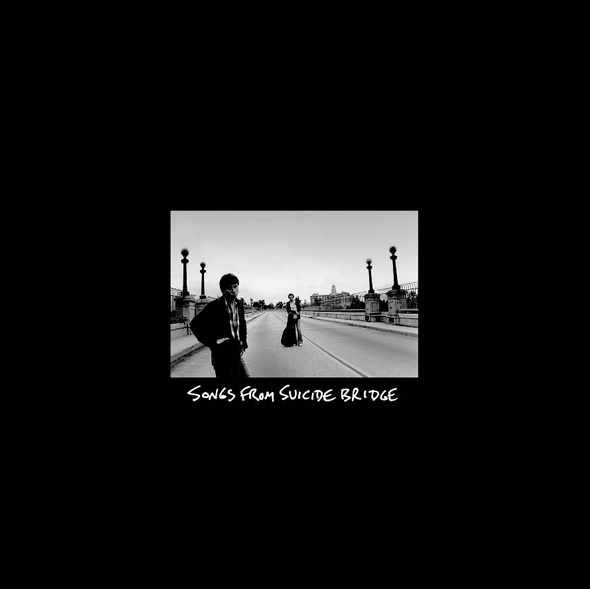

Photo courtesy of David Kauffman and Eric CaboorRecorded in a toolshed in Burbank in 1983, Songs From Suicide Bridge is the debut album from David Kauffman and Eric Caboor, two lonely songwriters who met by chance two years earlier in the basement of a Methodist church in Echo Park, Los Angeles. You certainly couldn’t accuse them of false advertising: Songs From Suicide Bridge is every bit as dark and depressing as the title would lead you to believe. But it’s also haunting and beautiful, a timeless DIY document of melancholy acoustic songs created by reluctant coffeehouse players who had given up on the idea of “making it” in a music industry increasingly geared toward MTV. For the album’s ghostly cover photo, they drove out to the Colorado Street “Suicide” Bridge in Pasadena, where over 100 people have ended their lives since the bridge’s construction in 1913. Kauffman and Caboor then pressed 500 vinyl copies of Songs on their own Donkey Soul Music label in June of 1984 and sent nearly half of them to college- and public radio stations—with little response in return.At that point, life took over: Caboor got married and had a son. Kauffman stayed in L.A. until 2001, when he moved back to his native New Jersey to help his ailing father. (In that time, the duo recorded two more albums together under the name The Drovers.) In May, Light In The Attic will reissue Songs From Suicide Bridge, and the album will hopefully receive the long overdue attention it deserves. I recently called Kauffman and asked him to share his recollections of the album he and his friend recorded in that toolshed over 30 years ago.You moved out to Los Angeles specifically to pursue music, didn’t you?

David Kauffman: Yeah, I moved out there in the latter part of ’78. I’m pretty sure it was October. I had majored in music in college, and my degree was in music education. But I had caught the songwriting bug while I was in college. After I graduated, instead of going into music education, I thought I’d give songwriting a shot. Initially I moved back to New Jersey, where I grew up, but then I decided I wanted to get as far away from home as I could without crossing the ocean.You ended up living in Hollywood just a few blocks from Mann’s Chinese Theater. That must’ve been a hell of a neighborhood in 1978.

This friend of mine was out there and he had an apartment on Franklin, just west of Sycamore. So I stayed with him a few days until I found an apartment of my own just a half a block away on Sycamore. But I landed in Hollywood because he already lived there. I didn’t have a car, so I was walking or taking the bus everywhere. Obviously, Hollywood Boulevard is pretty rough, but it wasn’t actually too bad of an area to live. It’s rougher as you go east from La Brea, so I was kind of on the west end where it wasn’t quite as bad. But yeah, it was interesting. [Laughs] Quite a different slice of life than what I was used to.You ended up working at Hamburger Hamlet.

Right. There was a Hamburger Hamlet at the time right across from the Chinese Theater. As far as I know, that’s no longer there. But it was a great setup because I could walk there. I was waiting tables and I had no expenses besides rent so I was able to save up a lot of money for a period of time. Within six months I had a car, so I was able to get around. And I had a lot of free time because I only had to work about 25 hours a week to make ends meet. So I was very fortunate to end up in that situation when I first got out there.At what point did you finally meet Eric?

October of 1981. It was an open-mic night at the Basement coffee shop, which was under a church in Echo Park. Eric and a friend of his were set to go on later in the evening, and I was scheduled to go on earlier. I think I did three or four songs and they approached me as I was getting up to leave. They said they liked my stuff, and we exchanged phone numbers. A couple of weeks later, Eric and I got together and played each other some of our stuff and talked about where we were going and what our hopes were.When did the Colorado Street “Suicide Bridge” come into play?

A little over a year after we first met, we came up with the concept of doing those songs and having that bridge tied in with them. We took those photos out there on the bridge in the spring of 1983, I’m pretty sure. A high school buddy of Eric’s, Albert Dobrovitz, he was kind of a photo buff, so he took a couple of rolls of black-and-white. But I wasn’t familiar with the bridge at that time. Eric knew of it because he grew up in Burbank.Did he tell you stories about it?

I think what happened was, we had the concept in mind with the songs we were thinking about doing, and we were sitting around thinking about what the title of the album would be. Somewhere in the conversation, the suicide bridge came up. So I asked Eric, “What’s that?” And he said it was the nickname for the Colorado Street Bridge over in Pasadena. He said there’d been a number of suicides there, and that it might be a good place to take some photographs. So it just went from there. The liner notes say that the concept for the record was for you to combine your “darkest and least viable works” onto one album. How did you arrive at that idea?

The liner notes say that the concept for the record was for you to combine your “darkest and least viable works” onto one album. How did you arrive at that idea?

Well, I think there were a number of factors. One was probably spite. [Laughs] We kinda realized that the material we were doing was not gonna be real acceptable, especially in terms of trying to woo the music business. We knew we weren’t gonna impress any of the music biz types, so we thought, “Why don’t we just take that to the extreme?” So we chose songs we knew wouldn’t be received real well, even though we thought some of them comprised our best material. I remember my girlfriend at the time thought it was a terrible idea. She kind of ended up winning out because that’s when Eric decided to write “One More Day (You’ll Fly Again)” to kind of lighten the feel of the album at the end, to give the listener an out.Your opening song, “Kiss Another Day Goodbye,” really sets a depressing tone with lyrics like, “I don’t know how long I can kiss another day goodbye.”

That song is like the flipside to “One More Day,” because “Kiss Another Day” sees the glass as half empty, and “One More Day” sees it as half full.Were you venting your frustration with the music industry on that song, or was there something deeper going on?

There’s something deeper going on, but frustration with the music industry was part of it. Both Eric and I are kinda lonely. It’s not that we don’t get along with people—it’s just kind of our makeup. To tell you the truth, I think the music industry thing was just a symptom of a bigger picture. And I think the bigger picture of the album is, “Is life worth living?” In a way, that’s the picture we face everyday when we get up in the morning. We don’t realize it’s there, because it’s like the 800-pound walrus in the room. [Laughs] But it’s funny because this album has been dormant for so long. Now that there’s a renewed interest, I’ve begun to re-think a lot of what went on. Like the first line of “Kiss Another Day,”— “I awoke in the early afternoon.” Right there, you know something’s not right, because people usually wake up in the morning, shower, get dressed, and go to work. So that set the tone—you knew it wasn’t a normal record. And it wasn’t just the feeling that I wasn’t getting anywhere with music. It’s also addressing the bigger question of, “Is life worth it, or should I just bust a cap in my head?”At the same time, you were coming to terms with the fact that you weren’t becoming successful.

I had the same plan that almost everybody who moves to L.A. does: You work a flexible job—that’s why you have so many waiters and waitresses out there—and shop your demo around during the day or play gigs at night. But Eric and I had the same problem: We couldn’t get gigs. I don’t care what kind of art you’re in—painting, acting, music—feedback is crucial. Eric and I knew we weren’t gonna be in arenas and stadiums and that type of thing. I was hoping to write songs and be known for my songwriting rather than my performing or my extracurricular activities. [Laughs] So I think that was an issue for both of us. We knew enough about songwriting—we spent our teens and early 20s just immersed in listening to albums—that we knew what was good material. We felt we had material worth hearing. We just weren’t finding an audience. So it sucked.You both had this pivotal moment when you went to see Danny O’Keefe play at McCabe’s in Santa Monica. What happened?

When we saw him live at McCabe’s, it was just him and his guitar. He was in such command of his guitar playing, his singing, his songwriting—he was a master at all three. It was just overpowering. I was pretty sure we were working on the album at that point, and when we left that show… I mean, talk about having the air let out of your sails in regards to assessing your own ability. [Laughs] After the show, we were feeling down and talking about it, and I can still remember looking at my girlfriend for some kind of relief, and she had nothing for us. That impressed on me even more how good he was. So that was a bad night for us. We thought, “If this guy didn’t make it, what chance do we have?” Of course he did fairly well for a few years, but he never got the recognition that he deserved.That must’ve been a painful realization.

It was good and bad. It was bad because we realized we’d never be as good as him. But it was good because we got confirmation that we weren’t making it because our stuff wasn’t any good. It was that we just weren’t gonna make it, just like O’Keefe didn’t. It also confirmed that we weren’t performers. We never considered ourselves performers, anyway—when we were performing a lot, it was maybe once a month. But that didn’t bother us because we never went to many live performances ourselves. We grew up listening to albums, so the album was more important to us. And we thought our songs deserved to be recorded.You recorded the album on a four-track in a converted toolshed in Eric’s backyard.

That’s how the liner notes describe it, but it wasn’t quite that bad. I’m not sure, but I think Eric’s dad actually built it so he could play music out there and he wouldn’t be making a racket in the house. It was probably about 15 feet by 12 feet, something like that. There was no plumbing or anything, but it was carpeted and we had a space heater.You pressed 500 copies of the album for $3000. Did that put you in the poorhouse?

Eric and I were both working and we were both single at the time, so the finances were actually no issue whatsoever. We recorded the album piecemeal, for the most part, so the thing that really saved us is that we weren’t spending any money on a studio. That was the saving grace because we could do take after take after take and not sweat about how long it was going.There were initially 13 songs, but only ten made the final album. What’s the story there?

At the time, we weren’t even considering the length of a vinyl album. We found that out when we went around looking for someone to press the album. Looking through a pressing plant’s information packet, we realized we had too many songs to fit on a record. It’s funny because the three songs that cut were probably even bigger downers than what’s on there. Two of them are about as bleak as you can get.Whatever happened to those songs? They weren’t included on the reissue.

We never did final takes of them. We had done a rough version of the album to see what sequence the songs should go in and that type of thing, but we never did final versions of those three because by that time we had learned that they wouldn’t fit. When Light In The Attic found out about these extra songs, they were intrigued by them, but we had nothing to give them. The versions I had were pretty rough.Why did you decide to call your label Donkey Soul Music?

Oh, man. We’d sit around for hours talking about this stuff. We got so little done, recording-wise, because we’d sit out there and chew the fat all night. Both of us were terrified of recording, I think, because as soon as you see that red light come on, you think, “All of posterity is gonna hear this.” So at one point we were throwing around names for our label, just trying to make each other laugh, and one of us came up with the name Asshole Records. Then we tried to veil it a little bit and suggested Donkey’s Hole. And then it morphed into Donkey Soul.So you get the record pressed and you send it off to radio stations. Did you get any feedback?

Somehow Eric got a list of college radio stations and public radio stations, so we sent out nearly half of the records we had. We figured the more we sent out, the greater chance someone would pick up on it. We got virtually no response from anywhere in L.A. But we got a very favorable response from two stations in particular, and I think the locations are telling: one was in Alaska and one was in Nova Scotia.Isolated places.

Right. Because obviously the people there could relate. They probably dropped the needle and thought, “Wow, this is where I’ve been for the last ten years!”To what extent are you still the same person who wrote those songs over 30 years ago?

Wow. That’s a great question. [Long pause] Not to get too heavy on you, but what’s going on is the human condition. We remain human, but have stages in our lives. The humanity of that album I can relate to, because I was there. One of the things that both Eric and I are proud of in regards to those songs is that they’re honest representations of where we were at the time. And I can relate to that, but at the same time, I can also appreciate that I’ve moved on. I’m still human; I’m just dealing with different stuff.J. Bennett is always dealing with different stuff. He is not on Twitter.

Advertisement

David Kauffman: Yeah, I moved out there in the latter part of ’78. I’m pretty sure it was October. I had majored in music in college, and my degree was in music education. But I had caught the songwriting bug while I was in college. After I graduated, instead of going into music education, I thought I’d give songwriting a shot. Initially I moved back to New Jersey, where I grew up, but then I decided I wanted to get as far away from home as I could without crossing the ocean.You ended up living in Hollywood just a few blocks from Mann’s Chinese Theater. That must’ve been a hell of a neighborhood in 1978.

This friend of mine was out there and he had an apartment on Franklin, just west of Sycamore. So I stayed with him a few days until I found an apartment of my own just a half a block away on Sycamore. But I landed in Hollywood because he already lived there. I didn’t have a car, so I was walking or taking the bus everywhere. Obviously, Hollywood Boulevard is pretty rough, but it wasn’t actually too bad of an area to live. It’s rougher as you go east from La Brea, so I was kind of on the west end where it wasn’t quite as bad. But yeah, it was interesting. [Laughs] Quite a different slice of life than what I was used to.

Advertisement

Right. There was a Hamburger Hamlet at the time right across from the Chinese Theater. As far as I know, that’s no longer there. But it was a great setup because I could walk there. I was waiting tables and I had no expenses besides rent so I was able to save up a lot of money for a period of time. Within six months I had a car, so I was able to get around. And I had a lot of free time because I only had to work about 25 hours a week to make ends meet. So I was very fortunate to end up in that situation when I first got out there.At what point did you finally meet Eric?

October of 1981. It was an open-mic night at the Basement coffee shop, which was under a church in Echo Park. Eric and a friend of his were set to go on later in the evening, and I was scheduled to go on earlier. I think I did three or four songs and they approached me as I was getting up to leave. They said they liked my stuff, and we exchanged phone numbers. A couple of weeks later, Eric and I got together and played each other some of our stuff and talked about where we were going and what our hopes were.When did the Colorado Street “Suicide Bridge” come into play?

A little over a year after we first met, we came up with the concept of doing those songs and having that bridge tied in with them. We took those photos out there on the bridge in the spring of 1983, I’m pretty sure. A high school buddy of Eric’s, Albert Dobrovitz, he was kind of a photo buff, so he took a couple of rolls of black-and-white. But I wasn’t familiar with the bridge at that time. Eric knew of it because he grew up in Burbank.

Advertisement

I think what happened was, we had the concept in mind with the songs we were thinking about doing, and we were sitting around thinking about what the title of the album would be. Somewhere in the conversation, the suicide bridge came up. So I asked Eric, “What’s that?” And he said it was the nickname for the Colorado Street Bridge over in Pasadena. He said there’d been a number of suicides there, and that it might be a good place to take some photographs. So it just went from there.

Well, I think there were a number of factors. One was probably spite. [Laughs] We kinda realized that the material we were doing was not gonna be real acceptable, especially in terms of trying to woo the music business. We knew we weren’t gonna impress any of the music biz types, so we thought, “Why don’t we just take that to the extreme?” So we chose songs we knew wouldn’t be received real well, even though we thought some of them comprised our best material. I remember my girlfriend at the time thought it was a terrible idea. She kind of ended up winning out because that’s when Eric decided to write “One More Day (You’ll Fly Again)” to kind of lighten the feel of the album at the end, to give the listener an out.

Advertisement

That song is like the flipside to “One More Day,” because “Kiss Another Day” sees the glass as half empty, and “One More Day” sees it as half full.Were you venting your frustration with the music industry on that song, or was there something deeper going on?

There’s something deeper going on, but frustration with the music industry was part of it. Both Eric and I are kinda lonely. It’s not that we don’t get along with people—it’s just kind of our makeup. To tell you the truth, I think the music industry thing was just a symptom of a bigger picture. And I think the bigger picture of the album is, “Is life worth living?” In a way, that’s the picture we face everyday when we get up in the morning. We don’t realize it’s there, because it’s like the 800-pound walrus in the room. [Laughs] But it’s funny because this album has been dormant for so long. Now that there’s a renewed interest, I’ve begun to re-think a lot of what went on. Like the first line of “Kiss Another Day,”— “I awoke in the early afternoon.” Right there, you know something’s not right, because people usually wake up in the morning, shower, get dressed, and go to work. So that set the tone—you knew it wasn’t a normal record. And it wasn’t just the feeling that I wasn’t getting anywhere with music. It’s also addressing the bigger question of, “Is life worth it, or should I just bust a cap in my head?”

Advertisement

I had the same plan that almost everybody who moves to L.A. does: You work a flexible job—that’s why you have so many waiters and waitresses out there—and shop your demo around during the day or play gigs at night. But Eric and I had the same problem: We couldn’t get gigs. I don’t care what kind of art you’re in—painting, acting, music—feedback is crucial. Eric and I knew we weren’t gonna be in arenas and stadiums and that type of thing. I was hoping to write songs and be known for my songwriting rather than my performing or my extracurricular activities. [Laughs] So I think that was an issue for both of us. We knew enough about songwriting—we spent our teens and early 20s just immersed in listening to albums—that we knew what was good material. We felt we had material worth hearing. We just weren’t finding an audience. So it sucked.You both had this pivotal moment when you went to see Danny O’Keefe play at McCabe’s in Santa Monica. What happened?

When we saw him live at McCabe’s, it was just him and his guitar. He was in such command of his guitar playing, his singing, his songwriting—he was a master at all three. It was just overpowering. I was pretty sure we were working on the album at that point, and when we left that show… I mean, talk about having the air let out of your sails in regards to assessing your own ability. [Laughs] After the show, we were feeling down and talking about it, and I can still remember looking at my girlfriend for some kind of relief, and she had nothing for us. That impressed on me even more how good he was. So that was a bad night for us. We thought, “If this guy didn’t make it, what chance do we have?” Of course he did fairly well for a few years, but he never got the recognition that he deserved.

Advertisement

It was good and bad. It was bad because we realized we’d never be as good as him. But it was good because we got confirmation that we weren’t making it because our stuff wasn’t any good. It was that we just weren’t gonna make it, just like O’Keefe didn’t. It also confirmed that we weren’t performers. We never considered ourselves performers, anyway—when we were performing a lot, it was maybe once a month. But that didn’t bother us because we never went to many live performances ourselves. We grew up listening to albums, so the album was more important to us. And we thought our songs deserved to be recorded.You recorded the album on a four-track in a converted toolshed in Eric’s backyard.

That’s how the liner notes describe it, but it wasn’t quite that bad. I’m not sure, but I think Eric’s dad actually built it so he could play music out there and he wouldn’t be making a racket in the house. It was probably about 15 feet by 12 feet, something like that. There was no plumbing or anything, but it was carpeted and we had a space heater.You pressed 500 copies of the album for $3000. Did that put you in the poorhouse?

Eric and I were both working and we were both single at the time, so the finances were actually no issue whatsoever. We recorded the album piecemeal, for the most part, so the thing that really saved us is that we weren’t spending any money on a studio. That was the saving grace because we could do take after take after take and not sweat about how long it was going.

Advertisement

At the time, we weren’t even considering the length of a vinyl album. We found that out when we went around looking for someone to press the album. Looking through a pressing plant’s information packet, we realized we had too many songs to fit on a record. It’s funny because the three songs that cut were probably even bigger downers than what’s on there. Two of them are about as bleak as you can get.Whatever happened to those songs? They weren’t included on the reissue.

We never did final takes of them. We had done a rough version of the album to see what sequence the songs should go in and that type of thing, but we never did final versions of those three because by that time we had learned that they wouldn’t fit. When Light In The Attic found out about these extra songs, they were intrigued by them, but we had nothing to give them. The versions I had were pretty rough.Why did you decide to call your label Donkey Soul Music?

Oh, man. We’d sit around for hours talking about this stuff. We got so little done, recording-wise, because we’d sit out there and chew the fat all night. Both of us were terrified of recording, I think, because as soon as you see that red light come on, you think, “All of posterity is gonna hear this.” So at one point we were throwing around names for our label, just trying to make each other laugh, and one of us came up with the name Asshole Records. Then we tried to veil it a little bit and suggested Donkey’s Hole. And then it morphed into Donkey Soul.So you get the record pressed and you send it off to radio stations. Did you get any feedback?

Somehow Eric got a list of college radio stations and public radio stations, so we sent out nearly half of the records we had. We figured the more we sent out, the greater chance someone would pick up on it. We got virtually no response from anywhere in L.A. But we got a very favorable response from two stations in particular, and I think the locations are telling: one was in Alaska and one was in Nova Scotia.Isolated places.

Right. Because obviously the people there could relate. They probably dropped the needle and thought, “Wow, this is where I’ve been for the last ten years!”To what extent are you still the same person who wrote those songs over 30 years ago?

Wow. That’s a great question. [Long pause] Not to get too heavy on you, but what’s going on is the human condition. We remain human, but have stages in our lives. The humanity of that album I can relate to, because I was there. One of the things that both Eric and I are proud of in regards to those songs is that they’re honest representations of where we were at the time. And I can relate to that, but at the same time, I can also appreciate that I’ve moved on. I’m still human; I’m just dealing with different stuff.J. Bennett is always dealing with different stuff. He is not on Twitter.