Photo Courtesy of Roe Ethridge and Andrew Kreps Gallery

Photo Courtesy of Roe Ethridge and Andrew Kreps Gallery

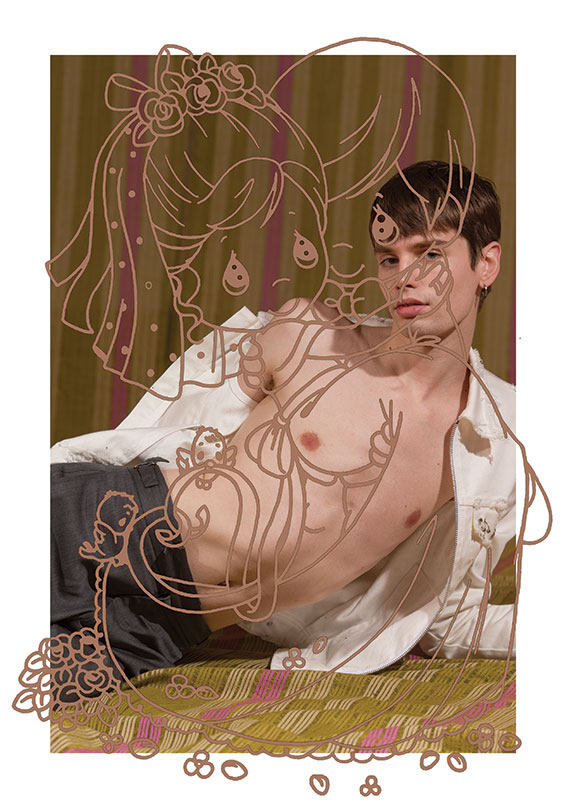

Photo by Logan Jackson

Roe Ethridge: I was born in Miami, and then we moved to Atlanta when I was about ten.Interesting. I was born in Bermuda, and then we moved to Pensacola, Florida.

I actually went to Florida State for two years.Oh, wow. I had pretty much left Florida by the age of two, so I can't really tell you much about Florida. But it's part of my lineage. We bopped around to South Carolina for a minute, and then to Arkansas. So, we kind of have a similar trajectory through the south. Has the South informed any of your work? I'm realizing that it definitely has for me, but I'm still figuring out exactly how and why.

I'm sure that it does. I think growing up there, there was some urgency to deny the influence of it, at least as something authentic. Being this suburban person who was more, especially in Atlanta, fascinated—in a negative way—by the generic middle-class conservative suburban thing, was both like a blessing and a curse, I guess.

It's an interesting question, and it's forever changing. There's never one answer. At this point, it's something that crosses my mind before I even start. I wonder if it's going to be something to push in a direction or to just pay attention to the fact that maybe there will be some discovery on this assignment that leads to something else. A lot of times it becomes part of an inventory that I go back to. It does happen often that it's best to not know the answer to that question, because that's what's interesting: discovery and not having a theoretical practice that is like, This is how you do it. I mean, I'm interested in different facets of making images, and sometimes it's not even taking a picture. It could be something that's so particular that it can't really be anything other than that advertisement or editorial. It only lives in one place, one time. That happens much more often than the other way around.

For a long time I've referred to this Warhol quote: "I want to get it exactly wrong." I always thought that was amazing, because on one level I was always fascinated with how to make something, and when I went to art school there was no technical teaching of how to make a perfect image. It was very how does that make you feel? talk therapy. So I think in a way I was much more interested in the conceptual because as I said earlier, I was rebelling against what seemed like the lame emotionality in what was supposedly "Southern photography"—selective focus or dramatic faces and stuff. I was more interested in "German Objective Photography," and the way that looked distant and neutral. It was a way to mirror that modern city that was Atlanta, and the suburbs. I think it tracked backwards into Steven Shore and his objective large-format stuff, and then Joel Sternfeld's more personal interactions with the everyday world. So that was where my education took me, less into how you make a professional photograph. To me, it was fascinating to make a good one, and I thought that everything I was doing was wrong. But like I said, I loved the notion of doing it wrong.

Looking over your imagery, I can see your voice present, even though there are multiple approaches. And I think that's ultimately a funny thing because that is the advice Philip-Lorca diCorcia gave me when I was assisting him. He said you have to find your voice, use it, and develop it. I was like, That's cool, but I have multiple voices. Not schizophrenic, I just can't imagine having only one. In a way, that's what I started doing. I just had a curated and organized survey show and, looking back on it, it's just a very slow conceptual art project. It was like it took 20 years to put all the pictures together because it seemed like they all went together. There were themes and compositional motifs and color, and ultimately there's a voice. It doesn't matter if it's a building or a portrait, still life of a building, or a picture of a woman, I can see that it's my picture and understand how I can apply that to things I was looking at yesterday or last year. It's almost like you didn't need to have a rationalization for why photography is perverse in that way.

That Baldessari thing has been fully absorbed to the point where it's understood. I don't even think about it anymore because there's no shock to it. We're also experts at consuming, so there's never a time where we're not trying to find that novel thing. In some ways, that's already been colonized and utilized. What's really bad is that we don't even know what's really bad anymore. How do you make it bad if bad is good? It's so bad it's good sometimes. And that's something I feel like I hear all the time. And I say that all the time, too. I don't even mean to use the word bad in the way I do.

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson

Photo by Logan Jackson