Mossless in America is a new column featuring interviews with documentary photographers. The series is produced in partnership with Mossless magazine, an experimental photography publication run by Romke Hoogwaerts and Grace Leigh. Romke started Mossless in 2009 as a blog where he interviewed a different photographer every two days, and since 2012 Mossless magazine has produced two print issues, each dealing with a different type of photography.Mossless was featured prominently in the landmark 2012 exhibition Millennium Magazine at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and is supported by Printed Matter, Inc. Their forthcoming third issue, a major photographic volume on American documentary photography from the last ten years titled The United States (2003-2013), will be published this spring.

Advertisement

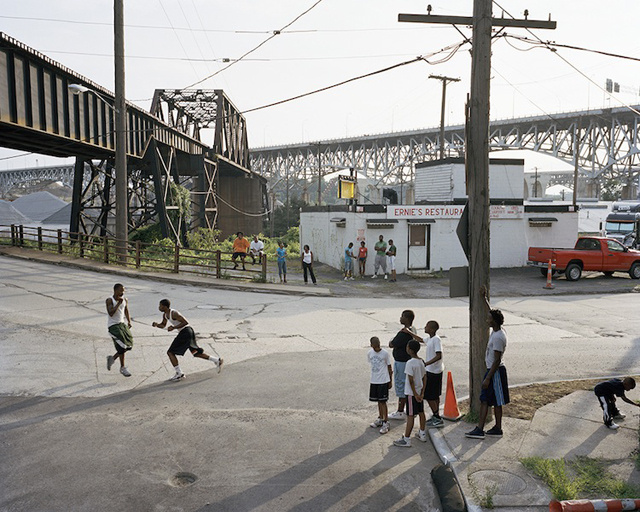

Riverfront, 2012Curran Hatleberg was one of the first photographers who inspired us to search for more documentary-style photos for the third issue of our magazine. His pictures, taken on roadtrips across America, are honest and naturally ambiguous. Whether it's a woman with a black eye or a memorial stuck in a tree, Curran's images make the viewer question the larger, unseen circumstances around his photos.In this column, we’ll be interviewing a bunch of photographers from the third issue of our magazine, Mossless. Like Curran, the other artists we've chosen shoot modern America, capturing the essence of what it's like to live in this country during this particularly difficult decade.Mossless: Tell us a memorable story from your travels across America.

Curran Hatleberg: A while back I was sitting in an empty barroom looking out the entrance to a dirty street. The door was propped wide open, framing a perfect view of the foot traffic and cars streaming by in the night. I studied thousands of insects as they whirled and smashed into a streetlight. I watched a nervous, skinny woman flash her gold teeth, then drop an orange rind on the sidewalk. Then I saw a sedan meet a concrete pillar at 50 miles an hour. The car lurched up the pole with vicious agility, going completely vertical before landing upside down. The whole event appeared slow and graceful and very far away. I stared, inactive, for what felt like a very long time, trying to decide if what I saw had actually happened or not. Before I was aware of my movements I was on my knees, breathing hard at the driver's side window. Everything smelled like gas. Glass and debris were strewn everywhere like confetti. Looking inside, the driver had blood streaming down his face in squiggled paths and was laughing uncontrollably. With the help of another man, I dragged him by the arms out of the window and onto the grass. The driver writhed on the ground in spastic fits of energy. A crowd developed around him, unsure what to do. It all happened very fast, but I clearly remember standing up and seeing one of the car's tires spinning purposely, as if the road were still underneath it.

Curran Hatleberg: A while back I was sitting in an empty barroom looking out the entrance to a dirty street. The door was propped wide open, framing a perfect view of the foot traffic and cars streaming by in the night. I studied thousands of insects as they whirled and smashed into a streetlight. I watched a nervous, skinny woman flash her gold teeth, then drop an orange rind on the sidewalk. Then I saw a sedan meet a concrete pillar at 50 miles an hour. The car lurched up the pole with vicious agility, going completely vertical before landing upside down. The whole event appeared slow and graceful and very far away. I stared, inactive, for what felt like a very long time, trying to decide if what I saw had actually happened or not. Before I was aware of my movements I was on my knees, breathing hard at the driver's side window. Everything smelled like gas. Glass and debris were strewn everywhere like confetti. Looking inside, the driver had blood streaming down his face in squiggled paths and was laughing uncontrollably. With the help of another man, I dragged him by the arms out of the window and onto the grass. The driver writhed on the ground in spastic fits of energy. A crowd developed around him, unsure what to do. It all happened very fast, but I clearly remember standing up and seeing one of the car's tires spinning purposely, as if the road were still underneath it.

Advertisement

How much traveling have you done for your photography?

Thirty-one years' worth.Your work is separated in two bodies: Dogwood and The Crowded Edge. What separates these series?

Both bodies of work are subsets of a larger unfinished project tied to route-less travel. Maybe they could be thought of as different chapters from the same bigger story; they both examine the same core idea, but from separate vantage points. The major difference is that The Crowded Edge is organized around a single event, while Dogwood is looser, revolving more around the way life advances, and how we get swept up and displaced from our own lives.

Thirty-one years' worth.Your work is separated in two bodies: Dogwood and The Crowded Edge. What separates these series?

Both bodies of work are subsets of a larger unfinished project tied to route-less travel. Maybe they could be thought of as different chapters from the same bigger story; they both examine the same core idea, but from separate vantage points. The major difference is that The Crowded Edge is organized around a single event, while Dogwood is looser, revolving more around the way life advances, and how we get swept up and displaced from our own lives.

Laurie, 2010Ambiguity is a very powerful element in many of your photos. In your interview with the Great Leap Sideways you elaborated on a photograph called “Denver, Tear,” providing a lot of emotional context. I’d like to hear the story behind “Laurie,” the red-haired girl with a bandage on her forehead. Can you tell us? Or is it better if we don’t know?

Ultimately supplying the backstory is problematic, because it can overpower the leaps of imagination a viewer can take all on their own. One of the things I like most about a photograph is that it’s silent, so the viewer’s personal invention and interpretation are invited to govern the meaning of a picture. For this reason I don’t want my pictures to assert what is happening, but rather suggest what might be happening. The best pictures depict a moment that is interesting precisely because of its lack of narrative clarity. They tempt us to believe a narrative structure while at the same time deliberately withholding that narrative, so the viewer's response can only be wonder.

Ultimately supplying the backstory is problematic, because it can overpower the leaps of imagination a viewer can take all on their own. One of the things I like most about a photograph is that it’s silent, so the viewer’s personal invention and interpretation are invited to govern the meaning of a picture. For this reason I don’t want my pictures to assert what is happening, but rather suggest what might be happening. The best pictures depict a moment that is interesting precisely because of its lack of narrative clarity. They tempt us to believe a narrative structure while at the same time deliberately withholding that narrative, so the viewer's response can only be wonder.

Advertisement

What has surprised you most about the people you’ve met?

Probably the ability people have to be both predictable and entirely incalculable.Curran Hattleberg is a Brooklyn-based photographer who has studied at the University of Colorado and the Yale School of Art. His work has been shown in galleries both nationally and internationally and is included in multiple collections. He currently teaches photography at the International Center of Photography and Norwalk Community College.Follow Mossless magazine on Twitter

Probably the ability people have to be both predictable and entirely incalculable.Curran Hattleberg is a Brooklyn-based photographer who has studied at the University of Colorado and the Yale School of Art. His work has been shown in galleries both nationally and internationally and is included in multiple collections. He currently teaches photography at the International Center of Photography and Norwalk Community College.Follow Mossless magazine on Twitter

Tear, 2011Curran Hatleberg

Chill, 2009Curran Hatleberg

Cigarettes, 2011Curran Hatleberg

Adrian, 2011Curran Hatleberg

Dog, 2009Curran Hatleberg

Waiting, 2012Curran Hatleberg

Alley, 2011Curran Hatleberg

Black Eye, 2012Curran Hatleberg