Eastlake Juvenile Court was supposed to be torn down 20 years ago. The official California Courts website shows a photo of the squat, beige building with the impatient caption, "The current overcrowded and deficient Eastlake Juvenile Courthouse." One of eight juvenile delinquency courthouses in the Los Angeles County juvenile justice system—which bills itself the largest in America—Eastlake is indeed crowded. By the time the day is in full swing, the hallway where young people wait to be called is packed with teenagers, their parents, grandparents, guardians, friends, boyfriends, and girlfriends, with a vibe not unlike a particularly shabby Department of Motor Vehicles full of Dodgers fans.

Advertisement

Eastlake is in Boyle Heights, a neighborhood of East Los Angeles with a population that's 94 percent Latino and where the median household income is $33,235 per year, according to the LA Times. The population that passes through the court largely reflects those demographics, though aside from East LA, the court also has jurisdiction over parts of South Central, Hollywood, Burbank, and Pasadena.In his chambers, Robert Leventer—who as a commissioner is essentially a judge in this court—sits before a wood veneer table covered with case files. A sculpture of Laurel and Hardy wearing old-timey black-and-white prison uniforms is perched high on a shelf. In his late middle ages, the gregarious Leventer has been has been working in LA juvenile courts for close to 30 years and a commissioner at Eastlake for two. Because this is a juvenile and not a full-fledged criminal court, defendants don't get a jury, have no right to bail, and proceedings are not open to the public. All of these things, Leventer volunteers readily, are problematic. The goal may be to rehabilitate youth rather than incarcerate, "but as a practical matter, we're locking them up," he tells me.

The young people who pass through Leventer's courtroom have mostly been arrested for either for a status offense—something that would not be illegal if the accused were over 18, such as skipping school—or a crime. Some are there solely for a transfer hearing, in which the court decides if the child's case should be heard in adult court. "This is a fairly tough area," Leventer explains, "so we don't see a lot of informal dispositions."

The young people who pass through Leventer's courtroom have mostly been arrested for either for a status offense—something that would not be illegal if the accused were over 18, such as skipping school—or a crime. Some are there solely for a transfer hearing, in which the court decides if the child's case should be heard in adult court. "This is a fairly tough area," Leventer explains, "so we don't see a lot of informal dispositions."

Advertisement

Which is to say most of the cases he hears center on serious offenses like assault and robbery, and they typically mean formal charges against the child."Most of the kids we see have psychological problems," Leventer continues. "They've had difficult lives, lots of trauma, many have been hospitalized." He estimates that 60 to 70 percent of the kids he sees have special needs of some kind or another.California's juvenile justice system has made strides in recent years, amid a national rethink that has seen scandal and reform in states from Texas to New York. "If you had asked me 15 years ago" how California's juvenile justice policies measure up nationally, "I would have said this state is harsh," says Daniel Macallair, executive director of the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice in San Francisco. "Now, we have some of the lowest rates of youth in our state institutions we've seen since we started measuring. By any measure, it's been a tremendous shift."

Macallair attributes this in part to an unprecedented drop in youth crime and arrests over the past several years. But policy changes have been significant, too, among them a shift away from reliance on state facilities to county juvenile halls, which allows young people to stay closer to home. And last year alone saw the passage of a number of measures softening punishments for youth, like Proposition 57, which makes it more difficult for prosecutors to try young people as adults. Likewise, Senate Bill 882 decriminalized fare evasion, which was the number one cause of youth citations in Los Angeles County. Local grassroots groups also successfully pushed for reform of the CalGang database, a non-public computerized list of alleged gang members used as a reference tool by law enforcement, which a state audit found to have added 42 individuals under the age of one.Aside from a tiny Korean American punk rocker type with long, bleached hair and Converse high tops, every child is brown or black.

Advertisement

Still, "Los Angeles has been slow to change," Macallair says. "It's got an entrenched bureaucracy that is, I'm sorry to say, very calcified and very resistant to reform."What follows, then, is a record of one day in Eastlake's juvenile court—and a window into how young people in one of America's largest and more progressive cities interact with the legal system at the dawn of the Trump era.Leventer dons his judge's robes and enters the courtroom, where the bailiff, clerk, court recorder, prosecutor, and defense attorney await him beneath two massive banks of fluorescent lights. The first two dispositions ("dispos" in courthouse speak) take less than five minutes, as one kid at a time is called in from the packed hallway and takes a seat next to the defense attorney. Parents and guardians sit against the rear wall, under a piece of paper that says "PADRES/ PARENTS" taped to the wood wainscoting. An interpreter sits next to parents when needed—which is often.The day's third dispo involves a 22-year-old man named Andres* who has been incarcerated at Ventura Youth Correctional Facility, a state youth "camp," for six years. All of the kids who live in the Los Angeles area go through Eastlake as part of the process of returning home from one of California's Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) facilities. Today, Andres is officially getting out.Andres is led into the courtroom from a door opposite the hallway waiting area, where kids coming from detention, as opposed to home, wait to be seen. Despite having his hands cuffed behind his back, Andres has an easy manner and a smile. He's wearing a bright blue prison-issue outfit, with "LA COUNTY JAIL XXX" stenciled on the back. The bailiff unlocks his handcuffs, and he's seated.

9:30 AM

Advertisement

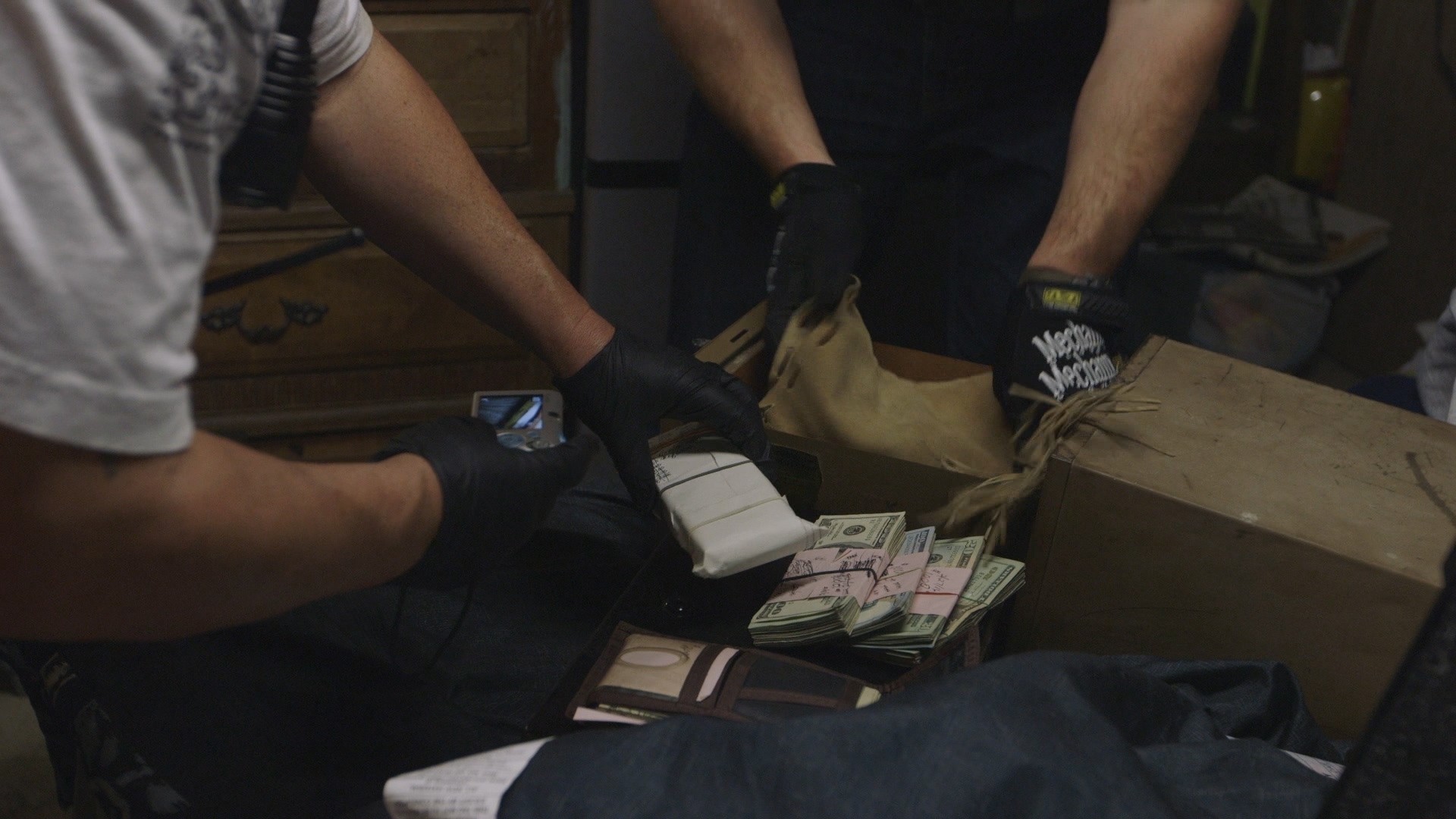

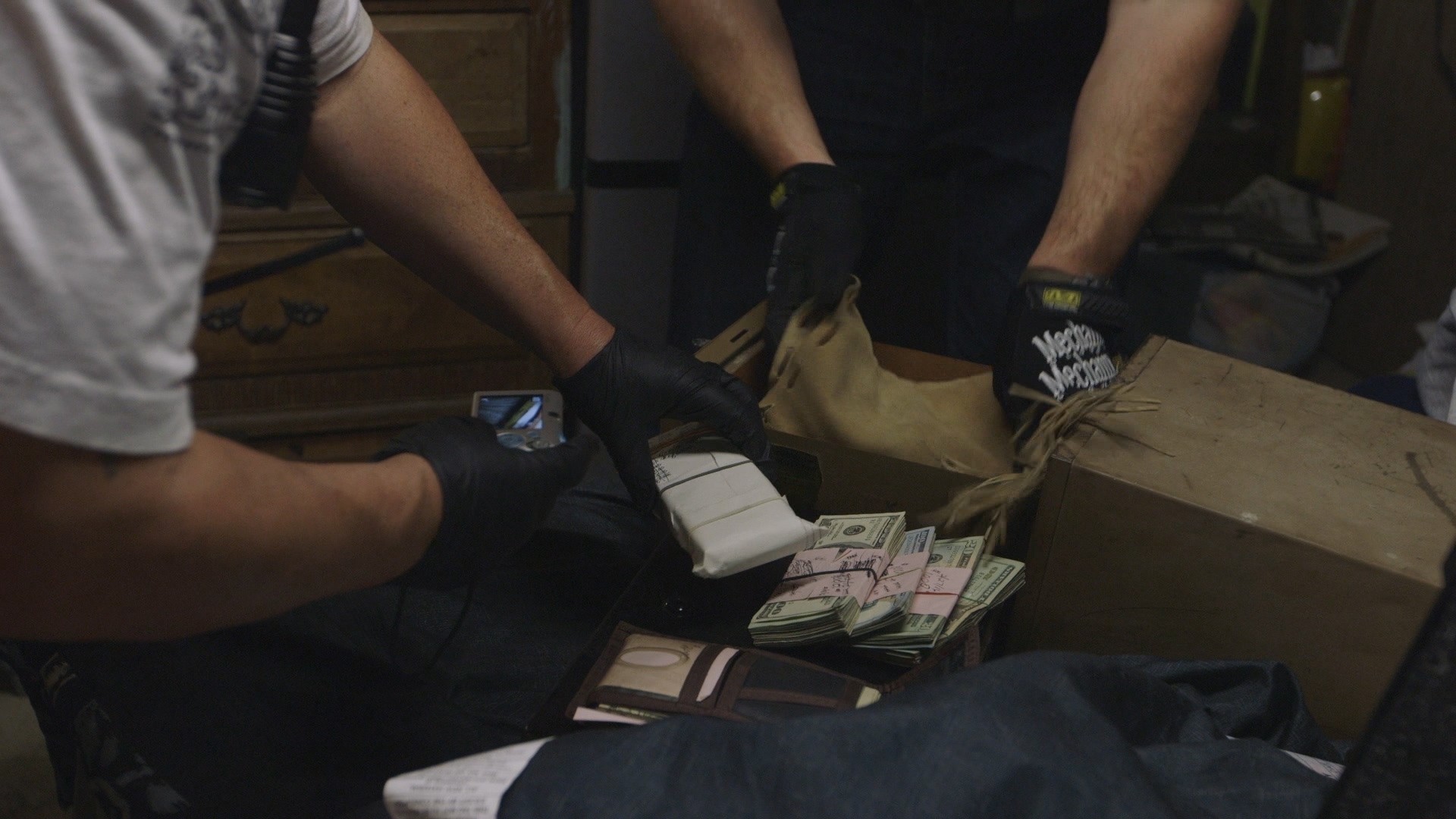

So you've been at Ventura for six years, Leventer notes. How was that?"It was cool," Andres says. Everyone laughs.Check out the VICE documentary on civil forfeiture, the process cops use to seize billions of dollars in cash and other assets. Pamela Villanueva, Andres's attorney, is one of a rotating cast of public defenders. (The prosecutor, Deputy District Attorney James Evans, stays put all morning.) She requests services for Andres after his release, including housing, continued help from the advocacy program Women of Substance & Men of Honor (which worked with him at camp), a TAP card for public transportation, and $400. All granted, except the cash. Villanueva asks again, this time for $200. No."[Andres] has been incarcerated a large percentage of his life, so there's uncertainty as to how he'll operate when he's outside those constraints," Villanueva explains to me later. When she started working with young people coming out of DJJ, they had few services available to help them with the adjustment, which can be brutal. She's heartened by the services young people like Andres are offered now but says they need more. "They're coming out of long-term incarceration. Everything is foreign to them. They need not only the wherewithal to get clothing and hygiene products, but they really need someone to go with them in the beginning till they can feel comfortable on their own."Help navigating the outside world can mean the difference between staying out or getting locked up again, she says.

Pamela Villanueva, Andres's attorney, is one of a rotating cast of public defenders. (The prosecutor, Deputy District Attorney James Evans, stays put all morning.) She requests services for Andres after his release, including housing, continued help from the advocacy program Women of Substance & Men of Honor (which worked with him at camp), a TAP card for public transportation, and $400. All granted, except the cash. Villanueva asks again, this time for $200. No."[Andres] has been incarcerated a large percentage of his life, so there's uncertainty as to how he'll operate when he's outside those constraints," Villanueva explains to me later. When she started working with young people coming out of DJJ, they had few services available to help them with the adjustment, which can be brutal. She's heartened by the services young people like Andres are offered now but says they need more. "They're coming out of long-term incarceration. Everything is foreign to them. They need not only the wherewithal to get clothing and hygiene products, but they really need someone to go with them in the beginning till they can feel comfortable on their own."Help navigating the outside world can mean the difference between staying out or getting locked up again, she says.

Advertisement

9:55 AM

Advertisement

"I tend to be a liberal guy, and I want to take a chance [on kids]," he tells me later. "But I've gone with my gut before, and people have ended up dead."He proceeds to describe a kid who spent two years in camp for possession of a knife. Leventer was advised that the kid was still a danger but gave him a shot and let him out. The child killed someone within a week, he says.The stream of kids keeps up at a brisk pace through the morning—it's unusual for a disposition to last longer than five minutes. Aside from a tiny Korean American punk rocker type with long, bleached hair and Converse high tops, every child is brown or black.There are hopeful moments over the course of the morning. A teenager wearing a tracksuit gets his case dismissed, and Leventer orders the record sealed. The kid beams, and his attorney gives him a high five and says, "Go be awesome!" Another young person has found gainful employment as a fisherman and appears to be on the straight and narrow. A baby-faced 13-year-old named Jesse is accompanied by his mother and great-grandmother. Leventer remarks that Jesse seems to have turned himself around, and the mom agrees. "He changed overnight!" She exclaims. Great-grandma affirms, "180 degrees!" Jesse's case is dismissed without prejudice, and his record is sealed. "Oh, Jesse!" Great-grandma cries with joy.There are dark moments, too. A 15-year-old charged with attempted murder fights a request to be transferred to adult court. A 17-year-old with "Ivy Midgets" tattooed on his cheek asks to be moved from Ventura to county jail, but he was supposed to go home to his sister's house last week and never showed. Then he got arrested again, and now the court is losing faith in him.

11:15 AM

Advertisement

A 15-year-old girl is called in, and her fiancé, uncle, and mom show up with her. She's doing OK, but the mom wants an ankle monitor on the girl. Granted. "I'm trying to save your life," Leventer tells her. "I hope you appreciate that."A wild-eyed and wild-haired kid is brought in from the detention waiting area. He's being held at Central Juvenile Hall, the facility attached to Eastlake that was the subject of a damning 2016 report by the Los Angeles Probation Commission, likening the hall to a "Third World country prison." He snatched a purse and ran, but the cops caught him. His attorney requests the Community Detention Program, the juvenile version of house arrest. Denied. The kid is cuffed and shuffles out through the door to the detention area.The next child, Marcus, is also brought in from detention. He wears a huge gray sweatshirt, gray work pants, and black sneakers. Marcus got locked up after getting into a physical altercation with his mother, who is present for the dispo. He was in foster care for two years and back with his mom for one week before the fight. She asks how to proceed when things get physical between them, because in the past when she has "put hands on him," the Department of Children and Family Services took him into foster care."I don't get along with her," Marcus says suddenly."Your mom?""Yes," he replies."But you want to go home?""Yes.""Do we need a 730?" Leventer asks Marcus's attorney—code for checking out whether this kid is playing with a full deck. He seems to have some trouble processing the questions asked of him.

Advertisement

They'll reconvene in a few weeks, and Marcus is led back out in cuffs. His mother leaves too."Mom is beating him," his attorney says.That's a wrap for the morning.

Illustration by Nicole Xu

12:30 PM

1:00 PM

Advertisement

Totten is gray-haired, gray-mustached—a dead ringer for Kris Kristofferson—and his courtroom is relatively democratic. Before the afternoon session begins, he meets with two probation officers, the prosecutor, a couple of defense attorneys, a rep from the Los Angeles Unified School District, and the therapist from MASA. The group broaches the progress, or lack thereof, in each case. Marijuana and meth are the two drugs that get mentioned over and over again.It was not a great week for the kids in Eastlake's drug court program. There have been several positive drug tests. Two kids cut off their electronic monitoring devices as well, and one of them, Melissa, ran away from home and lived on the street for five days."This is not a fun day," Totten says to the room. "I'm not enjoying today at all."Melissa's father is brought into the room to explain what's going on with his daughter and discuss options. He's carrying the ankle bracelet she cut off in a shredded bag, its green and red lights shining through the plastic. He doesn't know what to do for Melissa. Totten doesn't know what to do for Melissa. No one does. Melissa's father is directed to another room in the courthouse to return the ankle bracelet, her fate to be determined later.Several kids from the drug program now enter the courtroom—six boys and one girl in street clothes, many in Dodgers regalia—and sit in rows against the left wall. Two boys in gray juvenile hall work outfits are led in, their wrists cuffed to each other's, both with the chubby faces and smooth skin of small children. Finally, Melissa is led in, hands cuffed behind her back and head down, wearing orange scrubs and a high ponytail.

2:00 PM

2:15 PM

"You made commitments. What the hell is going on?" —Commissioner Robert J. Totten

Advertisement

The kids are called before the commissioner one at a time. Oscar, the first, has the day's only uncomplicated victory: He's stayed clean and abided by the court's rules, so he's being "up-phased," or promoted to the next stage in the program. Totten gives him a packet of gummy bears and a $25 gift certificate to AMC movie theaters. Everyone cheers."Oscar," Totten tells him. "Very proud of you. Keep up the good work."The rewards seem rather generic, but Totten says he tries to target incentives with an eye toward specific kids' interests. If a kid loves animals, he'll try to develop some programming where he can pursue that, "but our animal shelters are real restrictive as to who they'll allow to work there. We'd love to have them work with horses, but here in East LA, there aren't a whole hell of a lot of horses," Totten says.Several of the kids ask to approach the bench and speak to the commissioner privately. One of them, Cesar, has failed a drug test one too many times and is to be sent to Rancho San Antonio, a rehab program in Chatsworth. But Totten lets him have his one-on-one and eventually praises him. "You advocate well for yourself. It's a good skill." The rehab is scrapped; Cesar will instead stay at home under electronic surveillance. Asked what he said to convince Totten, Cesar admits he doesn't know what tipped the scales. "I just told him what I've been doing, what I'm going to do. That's what he likes. He likes honesty."

Advertisement

At Eastlake—as in life—the kids whose mothers don't have their backs face singular challenges. Miguel is one of them. ("I've never seen someone so opposed to their kid progressing," the attorney standing in for Miguel's usual counsel says in the meeting before the kids are brought back in.) The mother insists her son will fail at the drug court program, and you can see Miguel's face fall when she speaks about him this way. "It's heartbreaking," his public defender says. Despite the attorney's efforts, the probation officer, the DA, and Totten feel Miguel should be detained over the weekend. "These kids have to take responsibility," a probation officer says.When Miguel is called, his mother comes in. Like most of the parents in drug court, she needs an interpreter. She's older than the other parents, in her late 50s or early 60s."You made commitments. What the hell is going on?" Totten asks Miguel.Miguel barely moves his lips as he speaks. "I have communication problems with my mother." He denies having called her a fucking bitch, denies that a group of four of his friends showed up at their home uninvited, flashing gang signs at her. He says he isn't allowed to spend time with his brothers because his mother doesn't want him around them. "He's not a good influence," the DA calls out a few times to no one in particular. The attorney who defended him before he entered says nothing.Miguel is led out in cuffs.Totten now turns to Miguel's mother. "You have to find something to compliment him on. If you see him do something good, amplify it." After a few murmurs in which she continues to enumerate Miguel's misdeeds, the mother mentions that Miguel recently turned the lights off in their home, which was helpful. "Good, compliment him on it," Totten says.A new kid, Eduardo, is poised to start the drug court program today. He says marijuana is the only drug he's ever used. The counselors and attorneys grill him on this. You've never used meth? They ask. Spice? Heroin? PCP? Wax? No to all of the above. Just weed. Eduardo lives in Azusa, far from the drug court program, and will have to take the bus a long way in notoriously public transportation-challenged Los Angeles. He insists he can do it, and his mother says he will be there. The court decides he can participate, which means detention for at least one week to start. He's led out in cuffs.The court is adjourned for the day. Within 15 minutes or so, the building's halls are deserted, chairs empty.Later, Totten sits in his chambers under a framed article from the legal rag the Daily Journal featuring a black-and-white photo of the commissioner smiling with the headline "Hug Court." Adult drug courts have received a fair amount of attention—some of it critical—in recent years for their efforts to divert users away from jails and prisons and into rehab or home custody.Speculating on why drug court for kids hasn't gotten the same attention it has for adults, Totten opines, "We don't give kids enough attention in this country. You just have to look at the juvenile justice system to see that."*All juveniles' names have been changed in order to protect their right to confidentiality. This applies for adults whose offenses occurred when they were juveniles as well.Follow Lauren Lee White on Twitter.