David K. Purdy / Getty Images

Somewhat lost in Donald Trump's culture war with the NFL last month (yea, the one that used the National Anthem as a distraction from police brutality and racial inequality) was the President's critique of the league's player safety initiatives.Longing for the days of barbarism, when the NFL was as "great" as he'd like to make America, Trump said, "today, if you hit too hard…fifteen yards! Throw him out of the game!" According to him, the league is "ruining the game" with their new safety regulations. Ironically, the copious amounts of studies linking degenerative brain disease to football imply that the game appears to be ruining its players.This past July, Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) was found in 110 of 111 brains that were donated to science by deceased NFL players. The following September, Ann Mckee, director of the CTE Center at Boston University, told us that former New England Patriots star Aaron Hernandez progressed to stage 3 (out of 4) of the disease by the time he committed suicide. At 27 years old, Hernandez reportedly presented "the most severe case they had ever seen for someone of Aaron's age," his attorney, Jose Baez, asserted.While CTE is largely something that's discussed as it pertains to NFL players, the fact is Aaron Hernandez played a total of just 38 games in the NFL. That's close to half of what he played as a student athlete at Bristol Central High School and the University of Florida. Evidence would suggest head injuries are certainly an issue across lower levels of the sport as well.In efforts to address that issue, the Ivy League recently implemented an experimental rule for conference play, moving kickoffs from the 35-yard line to the 40-yard line—thus creating more touchbacks, eliminating the game's most violent play (the kick return), and reducing players' risk of helmet-to-helmet contact. Apparently, the experiment worked. As Robin Harris, executive director of the Ivy League, told the All-American, the conference saw a "clear reduction in concussions" as a result of the new rule.Aside from the reduction of two-a-day practices, other conferences within the NCAA made no such changes to actual gameplay, and saw no such progress in terms of player safety. So basically, many of their athletes still regularly study, prepare, and play through the fear of head injury. On the precipice of graduating on to their NFL careers, we spoke to some players who've overcome that fear by either working through it, embracing it, or altogether pretending it doesn't exist.Dorian O'Daniel, 23, linebacker at Clemson University I didn't read too much on [Aaron Hernandez's story], but I definitely saw the headlines. With a situation like CTE, it's definitely a subject that you have to take with a grain of salt, because football is a tough game. It's a physical game, and concussions are going to happen. At the end of the day your body is your business—you have to take care of yourself, first and foremost—but at the same time, your university's health staff or training staff or whoever it is that is in charge of making sure you're good to go and you're healthy, they have to take a sense of ownership over you as a student athlete as well. It goes both ways.You just can't think about it. The moment you step on the football field and you're worried about getting injured…that's when injuries happen. What I do to clear my head about injuries is go full speed, and use the right technique when tackling. Coaches have an influence too. They've seen it happen as well. They've seen guys go through the motions—even friendly fire. Teammates going full speed and someone around them gets caught in an area and gets rolled up on.If I have an opportunity to play at the next level, I'm going to take advantage of that, because I've been putting this work in my whole life…but if the cards aren't dealt in my favor, I'm fine with going on to the next step of my life.Naashon Hughes, 22, linebacker at the University of Texas

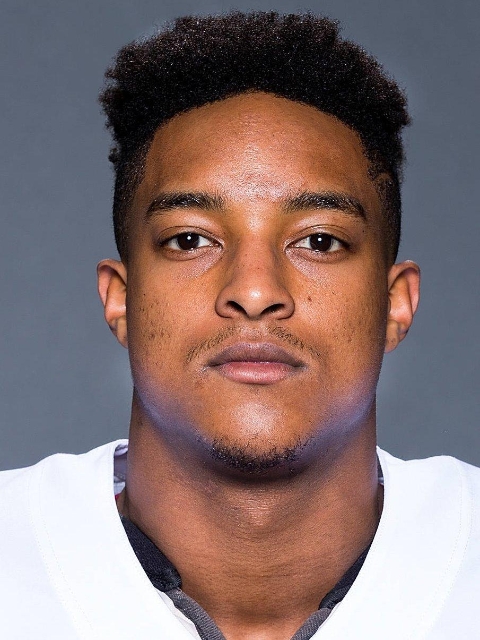

I didn't read too much on [Aaron Hernandez's story], but I definitely saw the headlines. With a situation like CTE, it's definitely a subject that you have to take with a grain of salt, because football is a tough game. It's a physical game, and concussions are going to happen. At the end of the day your body is your business—you have to take care of yourself, first and foremost—but at the same time, your university's health staff or training staff or whoever it is that is in charge of making sure you're good to go and you're healthy, they have to take a sense of ownership over you as a student athlete as well. It goes both ways.You just can't think about it. The moment you step on the football field and you're worried about getting injured…that's when injuries happen. What I do to clear my head about injuries is go full speed, and use the right technique when tackling. Coaches have an influence too. They've seen it happen as well. They've seen guys go through the motions—even friendly fire. Teammates going full speed and someone around them gets caught in an area and gets rolled up on.If I have an opportunity to play at the next level, I'm going to take advantage of that, because I've been putting this work in my whole life…but if the cards aren't dealt in my favor, I'm fine with going on to the next step of my life.Naashon Hughes, 22, linebacker at the University of Texas The actual nerves and jitters are worked out through practice, and workouts, and film review. Once the actual game comes, you're ready. Here in Texas, you start playing when you're a little kid. You dream about playing the game. You dream about making plays and big hits and things like that. The injuries are just another part of the game that you're not too concerned about.Around fourth or fifth grade, when I first started playing, my coach's son was the quarterback. He was running with the ball and he ducked his head down. [The coach] sat the team down, and we had an hour long discussion on proper tackling and proper neck and head positioning to make sure [injuries] don't happen.That's a part of getting to know your players and getting to know your teammates. You can sit [a player] down and talk to him, but there's also drill work that you can do to get him prepared and eliminate that fear—just by teaching him proper techniques and safe techniques to tackle and run with the ball.Steven Parker, 21, defensive back at the University of Oklahoma

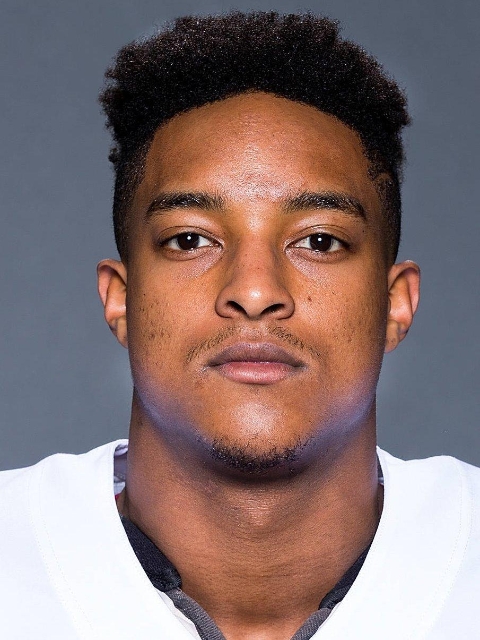

The actual nerves and jitters are worked out through practice, and workouts, and film review. Once the actual game comes, you're ready. Here in Texas, you start playing when you're a little kid. You dream about playing the game. You dream about making plays and big hits and things like that. The injuries are just another part of the game that you're not too concerned about.Around fourth or fifth grade, when I first started playing, my coach's son was the quarterback. He was running with the ball and he ducked his head down. [The coach] sat the team down, and we had an hour long discussion on proper tackling and proper neck and head positioning to make sure [injuries] don't happen.That's a part of getting to know your players and getting to know your teammates. You can sit [a player] down and talk to him, but there's also drill work that you can do to get him prepared and eliminate that fear—just by teaching him proper techniques and safe techniques to tackle and run with the ball.Steven Parker, 21, defensive back at the University of Oklahoma No player ever wants to think about getting hurt. The times you think about that are the times that you get injured. That's what I was taught as a kid—just brush it off and take it as it comes. You don't ever want to think about life after football—if you have too many [head] injuries or anything like that—you just play every snap like it's your last.You gotta play for you, or play for your family. Everybody has something that they play for. It's just like going out there on the playground. When you're on the playground, just throwing the football around, you're not thinking about getting hurt then. You're just having fun with your friends. That's how you have to play.[In the NFL] my approach is going to be a little different, but pretty similar. I'm still going to be playing for the love of the game. I'm still going to be playing for the people who sacrificed so much for me to put me in this spot.Read This Next: Degenerative Disease Found in 99 Percent of NFL Players' Donated Brains

No player ever wants to think about getting hurt. The times you think about that are the times that you get injured. That's what I was taught as a kid—just brush it off and take it as it comes. You don't ever want to think about life after football—if you have too many [head] injuries or anything like that—you just play every snap like it's your last.You gotta play for you, or play for your family. Everybody has something that they play for. It's just like going out there on the playground. When you're on the playground, just throwing the football around, you're not thinking about getting hurt then. You're just having fun with your friends. That's how you have to play.[In the NFL] my approach is going to be a little different, but pretty similar. I'm still going to be playing for the love of the game. I'm still going to be playing for the people who sacrificed so much for me to put me in this spot.Read This Next: Degenerative Disease Found in 99 Percent of NFL Players' Donated Brains

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement