FYI.

This story is over 5 years old.

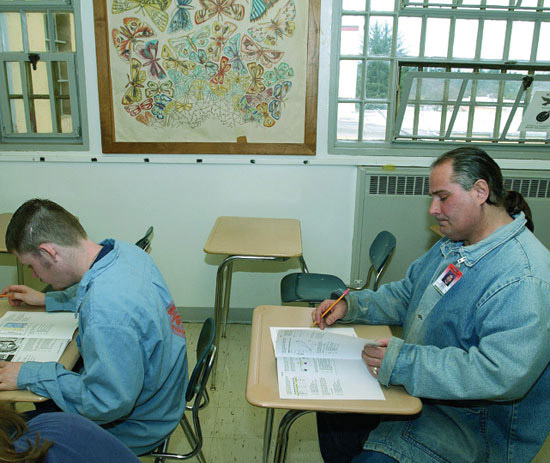

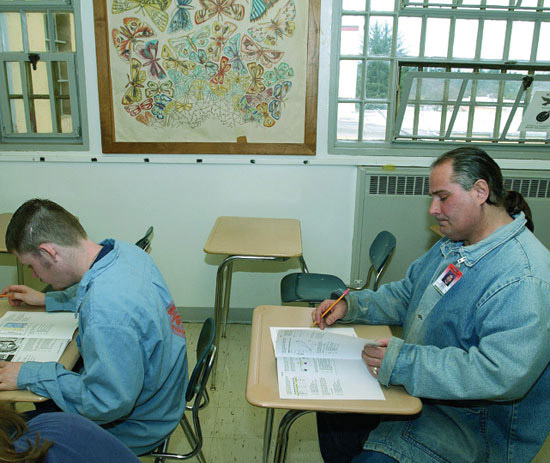

Institutionalized

I was sentenced to a mandatory-minimum 25-year sentence in federal prison when I was 22 years old. I've been in here for nine years now, and I've spent every day trying to improve, rehabilitate, and educate myself. I figured the best way to go about it...