Ullstein Bild / Getty Images

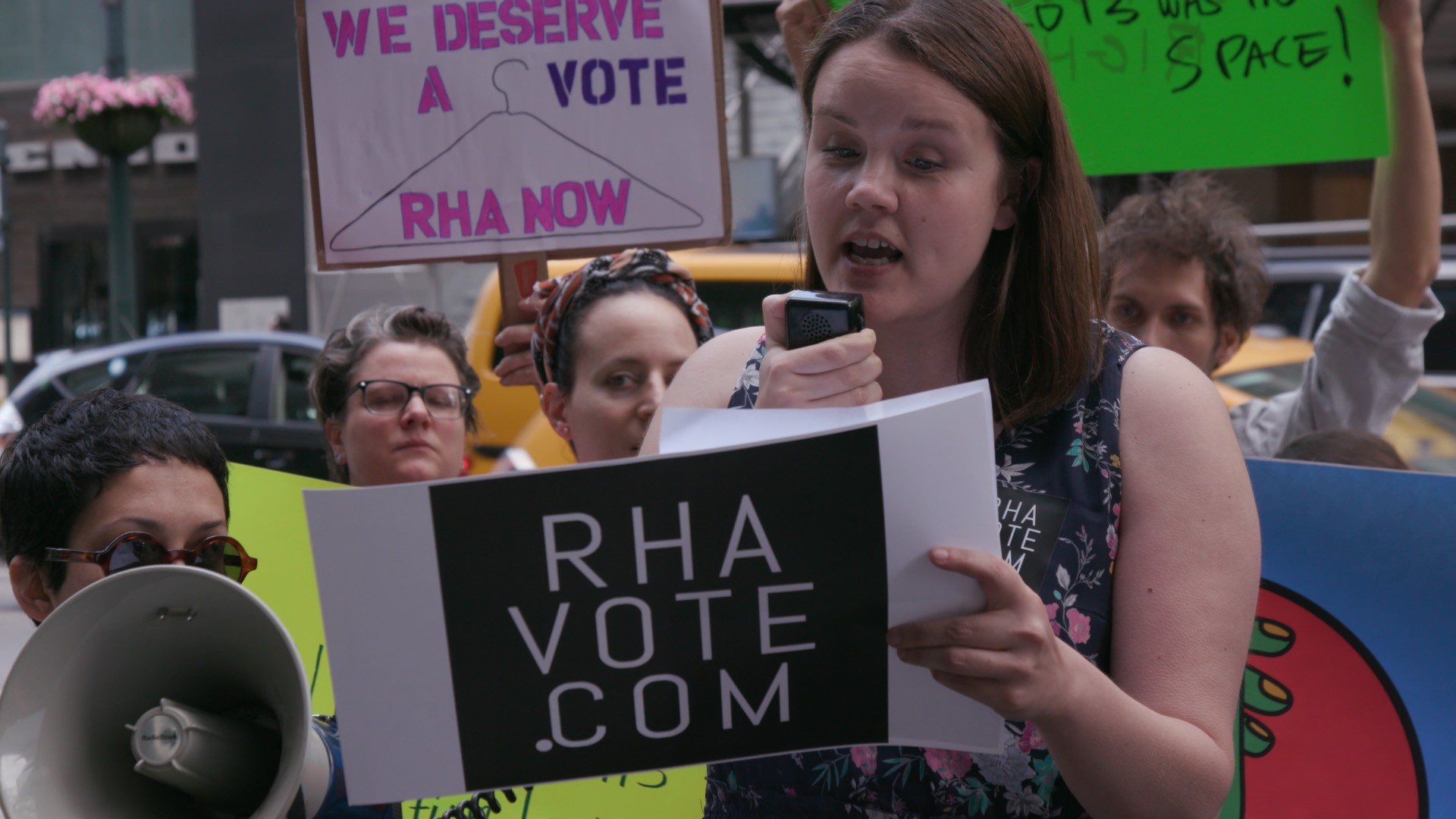

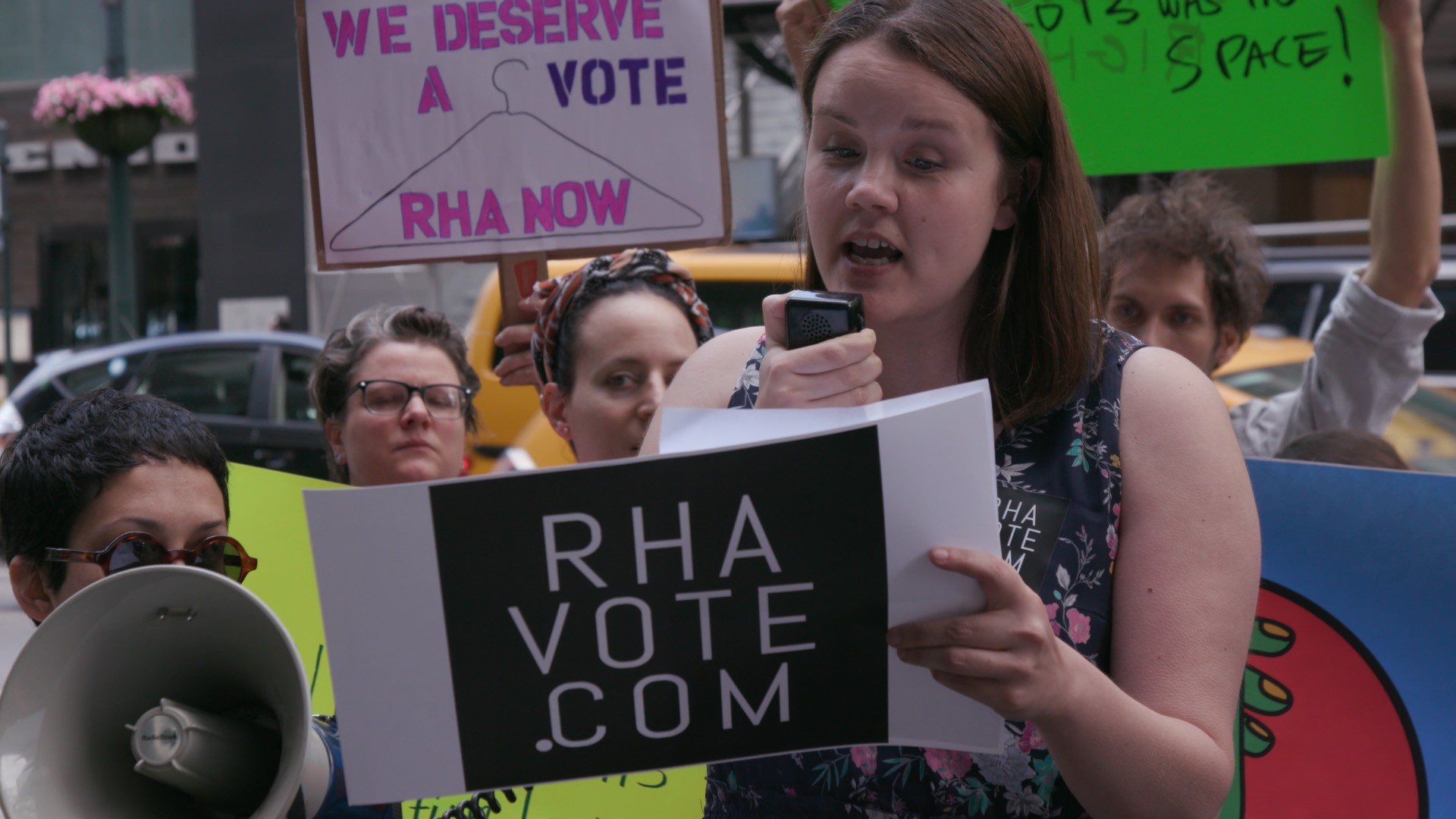

As of July 22, emergency contraception will no longer be available over the counter to Polish women aged 15 and over. Instead, these women seeking the morning-after pill will be required to visit a doctor and get a prescription. And, owing to the so-called "conscience clause," Polish doctors will be able to refuse medication if they feel the decision conflicts with their personal values and beliefs (that is, they can object on religious grounds). This has led to concerns among the Polish public and has been condemned by women's sexual and reproductive rights advocates, both in Poland and overseas.Two and a half years ago, the situation in Poland was slightly different. Following the 2014 advice of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and subsequent 2015 ruling of the European Commission, emergency contraception with ulipristal acetate—branded ellaOne across most of Europe and the equivalent of Plan B in the US—was deemed safe and effective to sell without prescription in the EU.Little more than a week later, the ruling Polish government Civic Platform announced that ellaOne would be made available over-the-counter in Poland. This decision was particularly significant in the Polish context, where reproductive law has become increasingly restrictive since the post-Communist transition and subsequent influence of the Polish Roman Catholic Church on policymakers. As such, this permissive change in the law was met with praise from reproductive rights groups.Nine months down the line, elections were held in Poland and the liberal-conservative Civic Platform party's majority was wiped out by the populist right-wingers Law and Justice (PiS). The new government brought a more traditionalist stance to social policy. In Poland, where around 90 percent of the population identifies as Catholic, this entailed an emphasis on church values. In 2016, some members of PiS backed a grassroots anti-abortion citizen's initiative to criminalize termination with a penalty of up to five years in prison for women and doctors. The Polish public's dismay and anger at this proposal culminated in the Black Monday #czarnyprotest general strike and nationwide demonstrations. This led to an overwhelming defeat in the Polish parliament and consequent abandonment of the proposal.

More From Tonic:

However, a few months after the Black Monday demonstrations—and fittingly enough, on Valentine's Day—the government floated proposals to repeal over-the-counter access to ellaOne. Polls conducted in the following weeks suggested that 63.5 percent of the electorate disagreed with the government's proposals. Naturally, this led to further demonstrations. Concurrently, Minister of Health Konstanty Radziwiłł took the time to suggest that a change in the law was necessary because Polish youth eat ellaOne "like candy." On the contrary, market research carried out the previous year had indicated that less than 2 percent of those under 18 were buyers of the pill.Nonetheless, this did not prevent PiS's proposal from being voted through parliament in late May and being signed off by PiS-friendly Polish president Andrzej Duda around a month later. The decision was immediately criticized by local and international women's sexual and reproductive rights groups. "We condemn this outrageous violation of the private lives and intimacy of women and men," the International Federation of Planned Parenthood said an in announcement on their site. "On women's rights within the European Union, we are faced with a dichotomy where girls living in the right place can get free contraception, including over-the-counter emergency contraception, while others face an uphill struggle."In Poland, even a teenager who's been raped has to fight to find a doctor who may—or may not—help her. Planned Parenthood added: "The new Polish law passed by the country's archaic authorities allows for the potential abuse of power by doctors who may feel that they have a right to judge the sexual lives of women based on their own moral convictions."According to a joint statement released by ASTRA (the Central and Eastern European Women's Network for Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health), the Polish government's decision also has practical implications. "UPA ECPs work by inhibiting or delaying ovulation. The sooner they are taken, the more likely they are to work before ovulation occurs. Given the importance of the timing for an effective use of postcoital contraceptive methods, restrictions to the free distribution of ECPs may violate a number of rights, including the rights to health, non-discrimination, gender equality, and to be free from ill-treatment."In addition, Dorota Zaprzalska, a 26-year-old student from Warsaw, raises financial concerns around the restricted access to ellaOne. "I'm mad mostly about the economical reasons. Let's take my friend's case. She will have to pay 100 to 200 zloty [$27-55] for a visit to not be sure if this person's going to give a prescription. And she might [still] have to go to another doctor. Let's say that this time she's lucky and her friend helped her so she's paying 50zl [$14], so it's already like 250zl [$69]," Zaprzalska says. "Then she's going to the pharmacy and without any prescription discount you have to pay 150zl [$41]. In the end, you're paying 400zl [$110] and you're asking yourself what the fuck for. And imagine—there are so many girls who will not be able to afford it.""There will be a greater number of illegal and dangerous abortions, which is dangerous to women's health and lives and carries social and economical costs," Natalia Jakacka—a doctor and reproductive rights activist from Warsaw—told Politico following the initial vote. "Many doctors will dodge writing ellaOne prescriptions, citing so-called 'conscience clause.'"With the next parliamentary election due in two years, the law may yet change again. However, Zaprzalska isn't particularly optimistic. "I'm just afraid that it's going to take another five years and through these five years, for a decision that is purely political and ideological, how many girls are going to get hurt? And lost in sorrow and depression? How many children are going to become orphans?"Read This Next: Wisconsin Bill Would Ban Doctors From Learning How to Perform Abortions

Advertisement

Advertisement

More From Tonic:

However, a few months after the Black Monday demonstrations—and fittingly enough, on Valentine's Day—the government floated proposals to repeal over-the-counter access to ellaOne. Polls conducted in the following weeks suggested that 63.5 percent of the electorate disagreed with the government's proposals. Naturally, this led to further demonstrations. Concurrently, Minister of Health Konstanty Radziwiłł took the time to suggest that a change in the law was necessary because Polish youth eat ellaOne "like candy." On the contrary, market research carried out the previous year had indicated that less than 2 percent of those under 18 were buyers of the pill.Nonetheless, this did not prevent PiS's proposal from being voted through parliament in late May and being signed off by PiS-friendly Polish president Andrzej Duda around a month later. The decision was immediately criticized by local and international women's sexual and reproductive rights groups. "We condemn this outrageous violation of the private lives and intimacy of women and men," the International Federation of Planned Parenthood said an in announcement on their site. "On women's rights within the European Union, we are faced with a dichotomy where girls living in the right place can get free contraception, including over-the-counter emergency contraception, while others face an uphill struggle."In Poland, even a teenager who's been raped has to fight to find a doctor who may—or may not—help her. Planned Parenthood added: "The new Polish law passed by the country's archaic authorities allows for the potential abuse of power by doctors who may feel that they have a right to judge the sexual lives of women based on their own moral convictions."

Advertisement