Leo Jai is currently detained in Australia's Christmas Island detention centre. Each week, he writes a dispatch for VICE from the inside. You can read his others here.How long would it have taken for Stevie Wright from the Easybeats to get locked up on Christmas Island? In his day, the drug addicted singer was charged with housebreaking and arrested for heroin abuse. Or AC/DC’s Scottish-born vocalist Bon Scott, who served nine months in juvenile detention for unlawful carnal knowledge, escaping custody and theft.

Advertisement

I’m mulling this over sitting in the rec room of the Christmas Island detention centre, watching an old episode of Countdown on the TV. Memories of my teen years growing up in Australia’s suburbs flood back. I’ve lived in this country for over 50 years. The past year has been spent on Christmas Island, fighting deportation back to a country I don’t even remember living in. All because Peter Dutton decided I am a person of “bad character.” How many of the iconic Australian musicians that Dutton and I grew up listening to—so many of them immigrants like me—would he had deemed of "bad character" as well?The day I arrived here remains a painful memory.The transfer to Christmas Island was made in the small hours of the morning. The minivan interior was cold and the Serco driver, a slightly built Sudanese man, seemed to be having problems working out the cabin heat controls. The officer in charge, speaking in a thick English midlands accent motioned toward the heater dial in the centre console and told him to watch his speed. I'd spent the past 15 minutes nervously eyeing the speedo as we flew along the dark winding road, wondering when one of the three-man Serco escort would pick up on the fact he was driving 40 kilometres over the 100 kilometre speed limit.The truth is, at that point in the proceedings, I actually longed for the relief a fatal accident might bring. But how did it come to this?

Advertisement

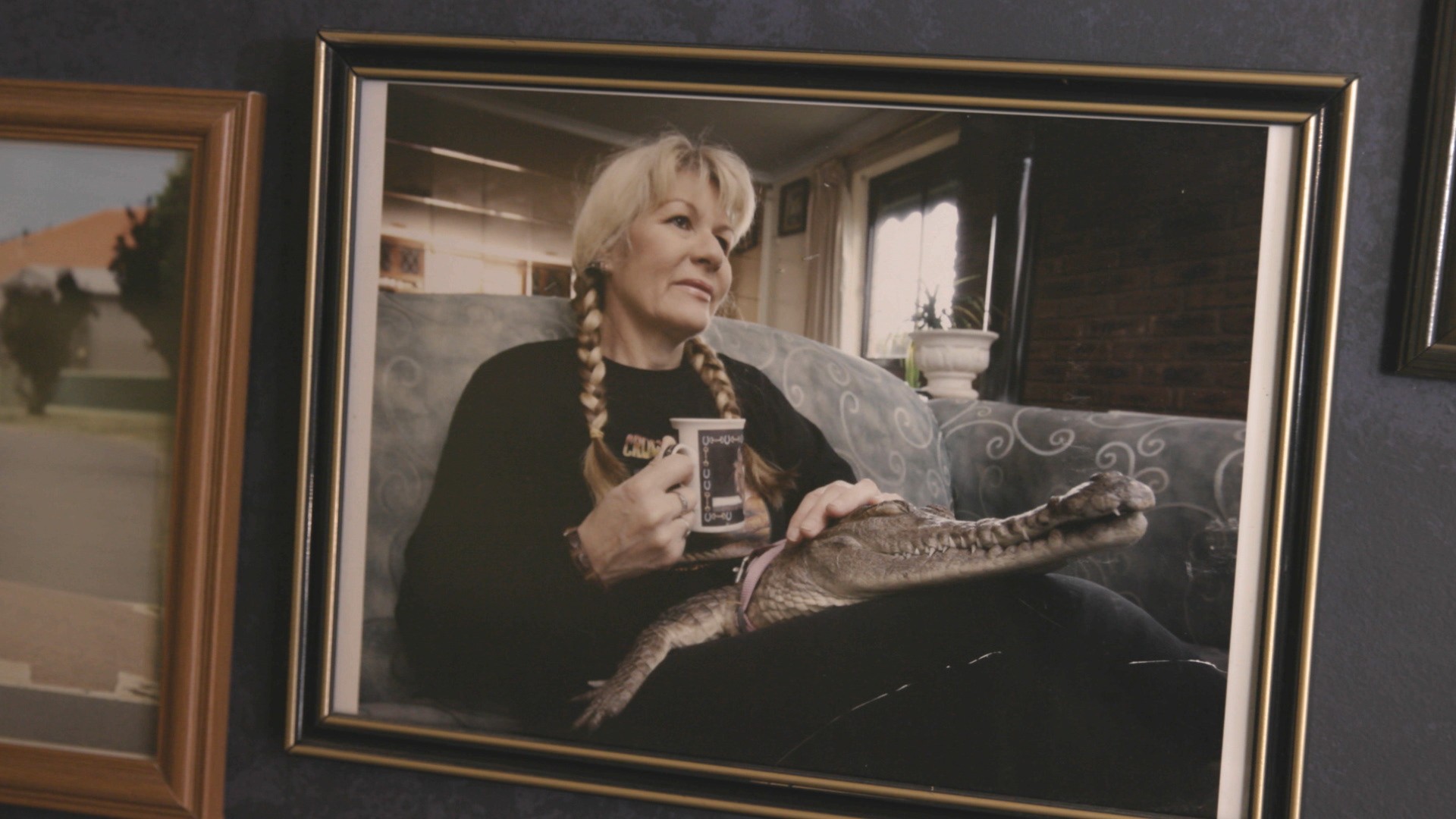

WATCH: VICE Meets Australia's Suburban Crocodile Foster Mum, Vicki

Well, in June 2016 the Honourable Peter Dutton MP stood up in Parliament and proudly boasted that he'd cancelled the visas of more than 1,000 non-citizens. Of these, 137 of were members of organised gangs. Nobody really bothered to ask him what the others did to deserve deportation.But many of the men locked up on Christmas Island are here on “character grounds”—an indiscernible matrix decided pretty much solely by Peter Dutton. Legislation changes in 2014 gave the immigration minister sweeping discretionary powers to cancel the visas of non-citizens.And the stories of injustice are numerous. Many detainees have lived in Australia since their childhood, and many are one-time offenders with no criminal past. Because the legislation is retrospective, many are being picked up for incidents that happened decades ago. Others have been detained for little more than traffic offences.One man had been fined by his local council for burning off in his suburban backyard during a fire ban. He's now been in detention here on Christmas Island for two years. Chillingly, some people here have no criminal charges at all. If you have charges laid against you that are subsequently dropped and dismissed, you now run the risk of having your visa cancelled on the claim that you present a “future risk to the community.” These people are being detained for years.

Advertisement

Not weeks or months. Years.These are the people Peter Dutton refers to as “some of the country's most hardened criminals.” I am one of them. I can assure you I am most certainly not a “hardened criminal.”Life here is an existence, not a life. The centre, which currently houses just over 320 detainees, is the equivalent of a maximum security prison. Security cameras abound. Everything is wire mesh and steel bars. Cages within cages. Border Force and their Serco minions run the centre with all the fervour and zeal of a game of toy soldiers.We live locked down in cramped compounds of 50 people. The noise is constant, and for the first time in my life I suffer regular tension headaches. Two hours a day, at scheduled times, I am allowed out for recreation and gym. If I choose to miss a meal of oily food, a guard will visit my room and ask me if I intend to eat. Not because he is concerned for my health, but because a hunger strike carries the potential for bad publicity.My face is a tight mask of constant worry and anxiety. I listen to my wife’s voice on the phone, knowing that she is broken and I cannot help. I hide my tears from her. I don’t want to burden her further. I cannot give her anything to look forward to. Nor can I reassure my 96-year-old mother that I will ever see her again. Her condition has deteriorated in the year I have been here. When she passes away, I will not even be allowed to attend her funeral.

Advertisement

Let us call a spade a spade. The Christmas Island detention facility, like the network of onshore immigration centres, is a concentration camp. Not a detention centre or a processing facility, as they like to euphemistically refer to places like Manus and Nauru. History will not remember this dark era in Australia's history kindly.Stevie Wright actually met the other members of the Easybeats at a place called the Villawood Migrant Hostel, where they lived with their families when they first arrived in Australia. That very same hostel has now been converted into the Villawood Detention Centre. It’s a transformation that stands as a perfect testament to Australia’s changing attitude towards migration.As a hostel in the 60s it was filled with life—a place of hopes and dreams for migrants looking forward expectantly to a new life for their young families in the "lucky country." In its draconian present, Villawood houses only grief and despair. Its detainee population faces the grim prospect of permanent estrangement from their families and the only life they know for months, years. The suicides that happen there never make the mainstream news.What exactly happened to our nation in the space of my lifetime, I wonder, that those same immigrants who Australia welcomed with open arms and embraced as their own are today treated as “hardened criminals,” subhuman flotsam, and left to rot for months, if not years, in places like the Villawood Detention Centre? Or here, with me, on remote Christmas Island.Follow Leo on Twitter