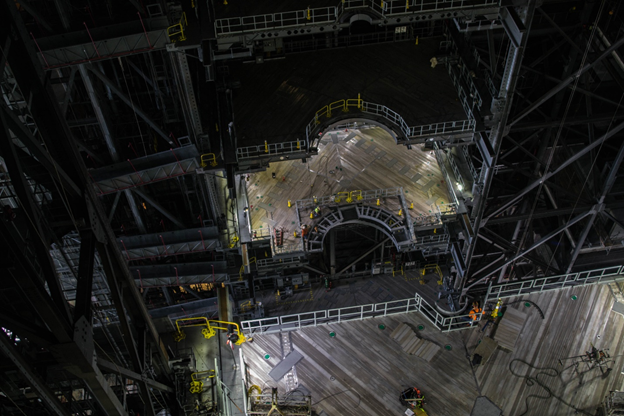

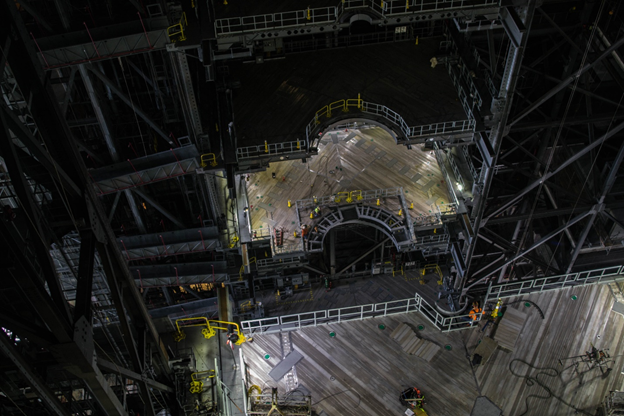

The media events leading up to SpaceX's cargo resupply mission (CRS-10) began two days before the scheduled launch from launch pad 39-A, one of three pads that on the sprawling 144,000 acres of Florida coast occupied by Kennedy Space Center. This was the pad that had seen the launch of the Saturn V rocket carrying the first crew to the moon on the Apollo 11 mission in 1969, as well as the final Saturn V mission carrying the Skylab space station into orbit in 1973. It was the pad of choice for the bulk of the space shuttle missions and now, for the first time in history, it would host a commercial rocket as part of its plan to transition to a "multi-user space port." This was a phrase I would hear repeatedly throughout the weekend from NASA personnel as they toured the press around Kennedy. It is, essentially, bureaucratic speak for Kennedy's transition to a heavily commercialized space facility. NASA is now just one of six organizations making use of Kennedy, which also includes heavyweight aerospace companies like SpaceX, Boeing, and Orbital ATK. As Kennedy Space Center director Bob Cabana described the transition, it allows "industry to provide our transportation to low-Earth orbit means the NASA team can focus on what we do best—exploration."Following the end of the space shuttle program in 2011, Kennedy stopped hosting rocket launches (these were subsequently done from the nearby Cape Canaveral Air Force base), and primarily became a place where payloads bound for the ISS were developed and, if coming from outside Kennedy, processed prior to being launched to the space station. It has also been ground zero for activities related to Orion and the massive Space Launch System, which will one day carry astronauts to Mars.As the space shuttle program was winding down, however, NASA was also acutely aware that it would need to find new ways of getting orbital, not to mention figuring out how to put all of Kennedy's shuttle-era facilities to use. The answer to both was the commercial crew program, and from 2010 to 2012, billions of dollars flowed through NASA to commercial space companies such as Boeing and SpaceX to develop viable crew transport systems to the International Space Station.

This was a phrase I would hear repeatedly throughout the weekend from NASA personnel as they toured the press around Kennedy. It is, essentially, bureaucratic speak for Kennedy's transition to a heavily commercialized space facility. NASA is now just one of six organizations making use of Kennedy, which also includes heavyweight aerospace companies like SpaceX, Boeing, and Orbital ATK. As Kennedy Space Center director Bob Cabana described the transition, it allows "industry to provide our transportation to low-Earth orbit means the NASA team can focus on what we do best—exploration."Following the end of the space shuttle program in 2011, Kennedy stopped hosting rocket launches (these were subsequently done from the nearby Cape Canaveral Air Force base), and primarily became a place where payloads bound for the ISS were developed and, if coming from outside Kennedy, processed prior to being launched to the space station. It has also been ground zero for activities related to Orion and the massive Space Launch System, which will one day carry astronauts to Mars.As the space shuttle program was winding down, however, NASA was also acutely aware that it would need to find new ways of getting orbital, not to mention figuring out how to put all of Kennedy's shuttle-era facilities to use. The answer to both was the commercial crew program, and from 2010 to 2012, billions of dollars flowed through NASA to commercial space companies such as Boeing and SpaceX to develop viable crew transport systems to the International Space Station. In 2014, this culminated with Boeing and SpaceX taking out long leases on two of Kennedy's main facilities. In an agreement brokered by Space Florida, a government agency dedicated to the economic development of aerospace activities in the state, Boeing leased the three orbiter processing facilities, where space shuttles underwent maintenance between flights.Later that year, SpaceX took out a 20 year lease on Launchpad 39-A, which it planned to refurbish to accommodate its Falcon Heavy rocket, which is basically three Falcon 9 rockets strapped together. If Kennedy's transition to a commercially oriented space facility was legally cemented when the leases were signed, the transition was symbolically consummated last weekend with the launch of the Falcon 9 to the International Space Station from 39-A.

In 2014, this culminated with Boeing and SpaceX taking out long leases on two of Kennedy's main facilities. In an agreement brokered by Space Florida, a government agency dedicated to the economic development of aerospace activities in the state, Boeing leased the three orbiter processing facilities, where space shuttles underwent maintenance between flights.Later that year, SpaceX took out a 20 year lease on Launchpad 39-A, which it planned to refurbish to accommodate its Falcon Heavy rocket, which is basically three Falcon 9 rockets strapped together. If Kennedy's transition to a commercially oriented space facility was legally cemented when the leases were signed, the transition was symbolically consummated last weekend with the launch of the Falcon 9 to the International Space Station from 39-A. "This is an exciting time for space flight," Cabana told the press pool during a tour around Kennedy. "This flight on Saturday cements who and what we are: a multi-use spaceport. Everything we have planned and put into place is coming to reality when we launch off pad 39-A."The question, though, was whether the launch would be pulled off as planned. On Friday, SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell confirmed that an anomaly had been discovered in the second stage of the Falcon 9, but said she was confident that the rocket would fly the following morning. But the veteran space reporters in the pool, some of whom had been covering spaceflight for nearly three decades, were far from assured.Scrubbing a rocket launch is the name of the game in the space business, and everyone was counting on Elon Musk being particularly conservative this time around. Although SpaceX had a successful return to flight last month after the rocket explosion last September, this cargo resupply mission to the ISS was far more valuable—another screw up be disastrous for SpaceX.

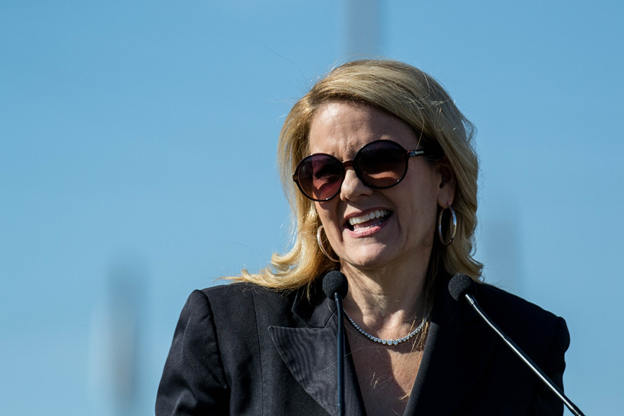

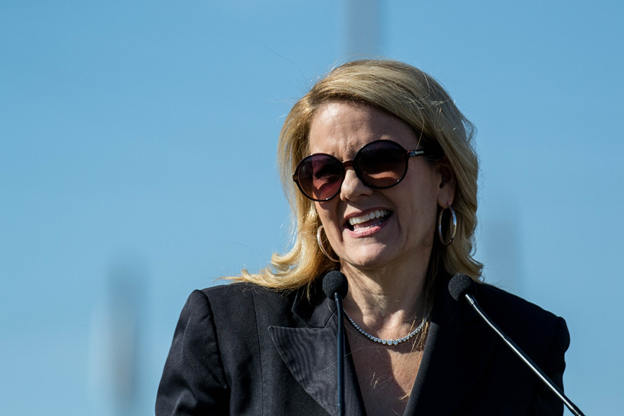

"This is an exciting time for space flight," Cabana told the press pool during a tour around Kennedy. "This flight on Saturday cements who and what we are: a multi-use spaceport. Everything we have planned and put into place is coming to reality when we launch off pad 39-A."The question, though, was whether the launch would be pulled off as planned. On Friday, SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell confirmed that an anomaly had been discovered in the second stage of the Falcon 9, but said she was confident that the rocket would fly the following morning. But the veteran space reporters in the pool, some of whom had been covering spaceflight for nearly three decades, were far from assured.Scrubbing a rocket launch is the name of the game in the space business, and everyone was counting on Elon Musk being particularly conservative this time around. Although SpaceX had a successful return to flight last month after the rocket explosion last September, this cargo resupply mission to the ISS was far more valuable—another screw up be disastrous for SpaceX. As of Saturday morning, there was still no news on whether the rocket would launch, so bleary-eyed I took the elevator up 46 stories to the roof of the VAB and waited for news. As launch time drew nearer, the reporters on the VAB roof got word that all systems were go. Yet with only 13 seconds left to launch, Musk called it off, citing a small anomaly with the steering mechanism. The rocket was "99% likely to be fine," Musk tweeted, "but that 1% isn't worth rolling the dice. Better to wait a day."The next launch attempt was scheduled for Sunday morning, a pleasant surprise—it is not uncommon for a scrubbed launch to be delayed for several days. However returning to Kennedy on Sunday morning, things didn't look good. There was a small storm moving east through Orlando and the reporters on the roof of the VAB took shelter from a light rain under large metallic vents. While launching a rocket in the rain isn't a problem, launching it when there is lightning is a no-go. With an hour left to launch, the rain let up and there had yet to be any lightning. All reports said the second stage anomaly had been fixed and the rocket was good to go.

As of Saturday morning, there was still no news on whether the rocket would launch, so bleary-eyed I took the elevator up 46 stories to the roof of the VAB and waited for news. As launch time drew nearer, the reporters on the VAB roof got word that all systems were go. Yet with only 13 seconds left to launch, Musk called it off, citing a small anomaly with the steering mechanism. The rocket was "99% likely to be fine," Musk tweeted, "but that 1% isn't worth rolling the dice. Better to wait a day."The next launch attempt was scheduled for Sunday morning, a pleasant surprise—it is not uncommon for a scrubbed launch to be delayed for several days. However returning to Kennedy on Sunday morning, things didn't look good. There was a small storm moving east through Orlando and the reporters on the roof of the VAB took shelter from a light rain under large metallic vents. While launching a rocket in the rain isn't a problem, launching it when there is lightning is a no-go. With an hour left to launch, the rain let up and there had yet to be any lightning. All reports said the second stage anomaly had been fixed and the rocket was good to go. I waited with bated breath until I saw the plume of smoke that precedes the brilliant orange flame spitting from the Merlin engine. The entire VAB shook as the Falcon 9 disappeared into the clouds, followed by a wave of cheers from spectators gathered on the lawn outside of Kennedy's press site. The photographers on the roof lazily readjusted their cameras to the right of the launch pad, trying to make out the location of the landing zone at Cape Canaveral Air Force base against the slate grey Atlantic. About ten minutes later, an orange orb descended from the clouds, gracefully touching down on the pad, but this time the cheers greeting its return were drowned out by the sonic boom that followed its landing.

I waited with bated breath until I saw the plume of smoke that precedes the brilliant orange flame spitting from the Merlin engine. The entire VAB shook as the Falcon 9 disappeared into the clouds, followed by a wave of cheers from spectators gathered on the lawn outside of Kennedy's press site. The photographers on the roof lazily readjusted their cameras to the right of the launch pad, trying to make out the location of the landing zone at Cape Canaveral Air Force base against the slate grey Atlantic. About ten minutes later, an orange orb descended from the clouds, gracefully touching down on the pad, but this time the cheers greeting its return were drowned out by the sonic boom that followed its landing. It's difficult to describe what I felt as the photographers and reporters packed up their equipment and began filing of the VAB roof. I had witnessed the changing of guards, the ushering in of a new paradigm for space exploration. In all likelihood, the first humans to ride on one of Musk's rockets will launch from Kennedy, an occasion that will be just as momentous as the first humans to depart Kennedy for the moon.Still, as I headed to the parking lot, it was hard to shake a feeling of unease. For all their positive spin, phrases like "multi-user spaceport" and "commercial crew program," not to mention the SpaceX hat I had just been handed, couldn't help but remind me that the final frontier, the last great commons, has been all but entirely handed over to private interest.

It's difficult to describe what I felt as the photographers and reporters packed up their equipment and began filing of the VAB roof. I had witnessed the changing of guards, the ushering in of a new paradigm for space exploration. In all likelihood, the first humans to ride on one of Musk's rockets will launch from Kennedy, an occasion that will be just as momentous as the first humans to depart Kennedy for the moon.Still, as I headed to the parking lot, it was hard to shake a feeling of unease. For all their positive spin, phrases like "multi-user spaceport" and "commercial crew program," not to mention the SpaceX hat I had just been handed, couldn't help but remind me that the final frontier, the last great commons, has been all but entirely handed over to private interest. This is not to belittle the accomplishments of a company like SpaceX, which has managed to entirely change the way we think about life beyond earth in just 15 years. Rather, it's to acknowledge that as a species with spacefaring ambitions, we've placed ourselves between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, we cast our eyes to the stars and dream of journeying to other planets; on the other, we consistently cut funding to the public institutions that could make this possible. Indeed, Kennedy's transition to a multi-user spaceport was the product of necessity. When it couldn't afford to maintain many of its facilities after the end of the shuttle program, it was faced with two options: tear them down, or rent them out.During my four days at Kennedy, I watched the space center lead the charge into the era of commercial space flight. How this transition will affect the future of space exploration is still unclear. But what is certain is that, for better or worse, the folks at Kennedy are too busy looking up to bother looking back.Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.

This is not to belittle the accomplishments of a company like SpaceX, which has managed to entirely change the way we think about life beyond earth in just 15 years. Rather, it's to acknowledge that as a species with spacefaring ambitions, we've placed ourselves between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, we cast our eyes to the stars and dream of journeying to other planets; on the other, we consistently cut funding to the public institutions that could make this possible. Indeed, Kennedy's transition to a multi-user spaceport was the product of necessity. When it couldn't afford to maintain many of its facilities after the end of the shuttle program, it was faced with two options: tear them down, or rent them out.During my four days at Kennedy, I watched the space center lead the charge into the era of commercial space flight. How this transition will affect the future of space exploration is still unclear. But what is certain is that, for better or worse, the folks at Kennedy are too busy looking up to bother looking back.Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement