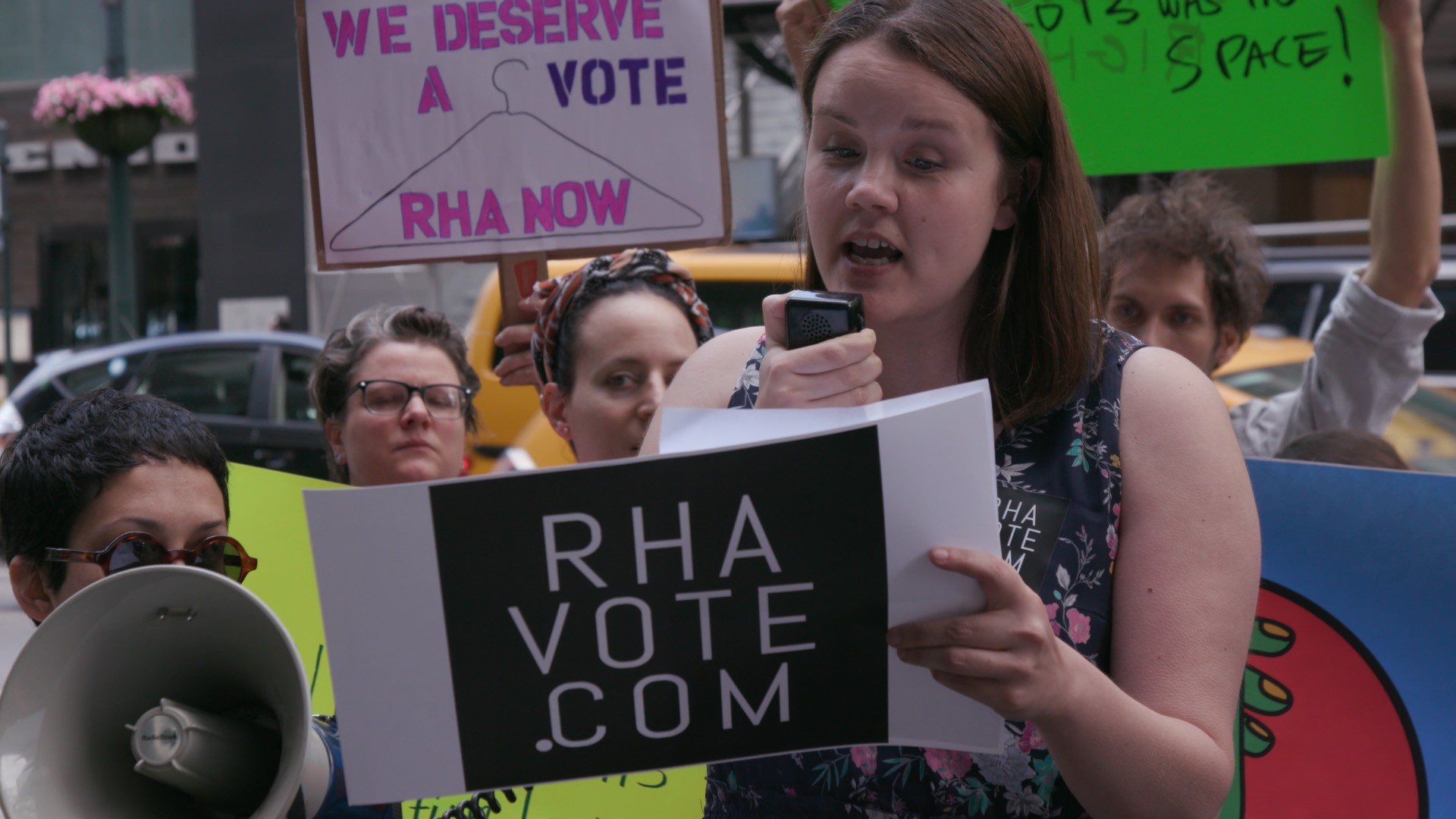

Randy Risling / Getty Images

"Why is it that organ donation isn't really covered in the press? Is it that we're all in denial of impending death? Isn't it strange?"This series of questions is being posed to me by Jeffrey Veale, a renal transplantation surgeon at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, where he's also an associate professor and the director of the UCLA Kidney Transplantation Exchange Program. Veale performs both kidney recoveries, or removals, and the subsequent transplants, which means he's involved in every step of the donation process. "And I also have the pink dot on my license—I'm an organ donor," he says.But he adds that there's a general lack of knowledge about the donation process, which could be at the root of some of the general misinformation and particularly pervasive myths surrounding transplantation. (No, celebrities don't get preferential treatment on the organ waitlist, and no, doctors aren't going to sell your parts on the black market—that's hella illegal.)Every situation is a little different, of course. But to clear up some of these enduring misconceptions, we got Veale to give us a step-by-step rundown on what actually happens in a standard deceased donation—that's when someone has died in an accident or from a medical issue like a heart attack or stroke has consented to let a stranger use their organs.EMTs and doctors try to save your life. Assuming there's been an accident, the process begins with the responding paramedics, who will do everything they can to rescue you after arriving on the scene. Life-saving efforts continue after emergency vehicles bring you to the hospital.Doctors confirm "brain death," which is the complete and irreversible loss of brain function. This means that while the heart is still beating and organs are still being oxygenated, there's no neurological activity happening in the brain or brain stem. A number of tests can confirm this—a brain-dead person will have no corneal reflex or gag reflex, for example—and two doctors not involved in the recovery or transplantation process must declare the person brain dead before the donation process moves forward.

More From Tonic:

Biopsy and evaluation. The potential donor remains on a ventilator to support body functions while experts from an organ procurement organization (OPO) make their way to the hospital. OPOs are regional nonprofits that coordinate the donation process, and there are 58 of them in the United States. (In Los Angeles, Veale works with OneLegacy.) These specialists, or specifically trained hospital staffers, communicate with and support the family throughout the process.Organs that can be transplanted include the heart, lungs, liver, kidney, pancreas, and small bowel, and some other tissues like the cornea, tendons, and skin. And smokers, diabetics, the elderly, and even people with certain cancers can be donors—so it's not just people in ideal health.Finding a match. How is the recipient determined? Well… it's complicated. Patients awaiting an organ are placed on a registry by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the national organization that oversees the transplantation system in the US.You've probably heard it referred to as a waitlist, but it isn't really a list, as it turns out—it's more akin to a pool. Rather than positioning patients in a first-come, first-served queue, UNOS collects information about everything from age to blood type to height and weight to social history to determine what eventual, theoretical donor will be the best match. Are your proteins compatible? What about your immune systems? Your blood type?When a donor becomes available, UNOS computers generate a dynamic list to determine where and for whom the organs would be most effective. Usually, Veale says, prioritization is a matter of how long you've been waiting and where you're located, but if you happen to match perfectly on all six human leukocyte antigens (proteins found on most cells in the body that are used to match you with a donor for transplant), they'll ship that kidney to you.From the ICU to the OR. When I tactfully ask Veale where the body is, uh, stored, so to speak, as the OPO works with the family and a donor is determined, he explains that there's no time for that. The donor stays in intensive care until they're ready to move to the operating room, where a biopsy is performed on each organ. A pathologist reads those results to determine if there are reasons it can't be used—that in the case of a kidney, for example, it isn't scarred and doesn't have diabetic damage—or if the results are clear."I can tell you that it's about one percent of all potential donors have organs that are actually suitable for transplantation," Veale notes, which is why it's so crucial to sign up to be a donor.After determining which, if any, body parts can be donated, organs are "recovered," or removed from the body. Just before removal, they're flushed with a cold preservation solution, and ice may be placed in the body cavities to help cool them down. After removal, organs are placed in preservation solution and packed in sterile containers with an icy, slushy mixture—you want to keep them cool, but not freeze them solid—so they can be transferred to the recipient center and transplanted.The organ is on the move. From there, things happen quickly. Veale says kidneys are some of the most tolerant organs in terms of time to transplant, and still, you only have up to two days to get one up and running in a recipient's body. The time limit differs from organ to organ—livers can also be on ice a bit longer, but the window for hearts and lungs tops out at between 6 and 12 hours.OPOs have certified couriers who take or organs from hospital to hospital or to and from the airport. Today, most major airlines will ship organs—and they get priority. In fact, you could have a kidney to thank for speeding up your wait on the runway. "If you're on a flight, and there's a kidney that they're also trying to fly to another hospital or another state, your flight will go to the front of the queue," Veale says. "Your flight will take off much sooner."It's transplant time. When the organ reaches its destination, receiving surgeons prep the patient and perform the transplant. Transplant recipients generally only receive basic, anonymous facts about their donor—that they were, say, a middle-aged woman from a neighboring community—but it's possible (and encouraged!) to send an anonymous thank you to the donor's family through the OPO that coordinated the donation.And it's important to note, Veale says, that one donor could end up saving more than one life. "Sometimes, people who donate organs, what they do might have been one of their greatest—I don't know if you'd call it an accomplishment, but one of the greatest things they do," Veale says. "Say you donate seven organs and you save seven people's lives. You could have a regular job—a regular life—and the lives you touch, the family members, friends, spouses… it can be one of your greatest contributions or achievements."Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Veale is a surgeon and professor at UCLA's Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital, but the correct name of the hospital is now the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center.Read This Next: This is What It's Like to Wait For an Organ Donation

Advertisement

Advertisement

More From Tonic:

Biopsy and evaluation. The potential donor remains on a ventilator to support body functions while experts from an organ procurement organization (OPO) make their way to the hospital. OPOs are regional nonprofits that coordinate the donation process, and there are 58 of them in the United States. (In Los Angeles, Veale works with OneLegacy.) These specialists, or specifically trained hospital staffers, communicate with and support the family throughout the process.Organs that can be transplanted include the heart, lungs, liver, kidney, pancreas, and small bowel, and some other tissues like the cornea, tendons, and skin. And smokers, diabetics, the elderly, and even people with certain cancers can be donors—so it's not just people in ideal health.Finding a match. How is the recipient determined? Well… it's complicated. Patients awaiting an organ are placed on a registry by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the national organization that oversees the transplantation system in the US.You've probably heard it referred to as a waitlist, but it isn't really a list, as it turns out—it's more akin to a pool. Rather than positioning patients in a first-come, first-served queue, UNOS collects information about everything from age to blood type to height and weight to social history to determine what eventual, theoretical donor will be the best match. Are your proteins compatible? What about your immune systems? Your blood type?

Advertisement

Advertisement