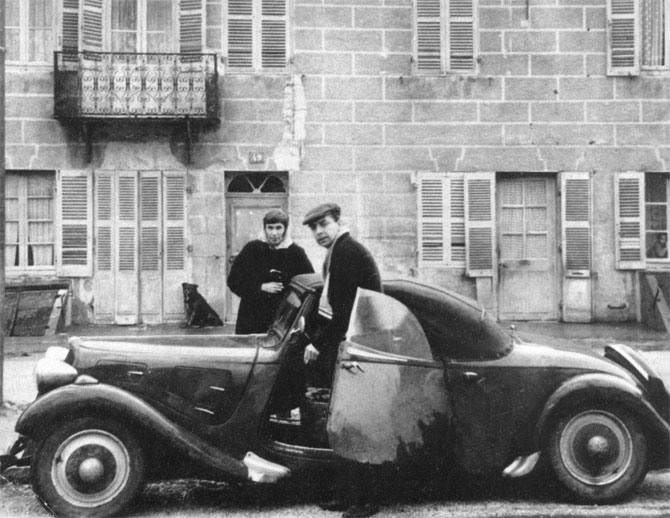

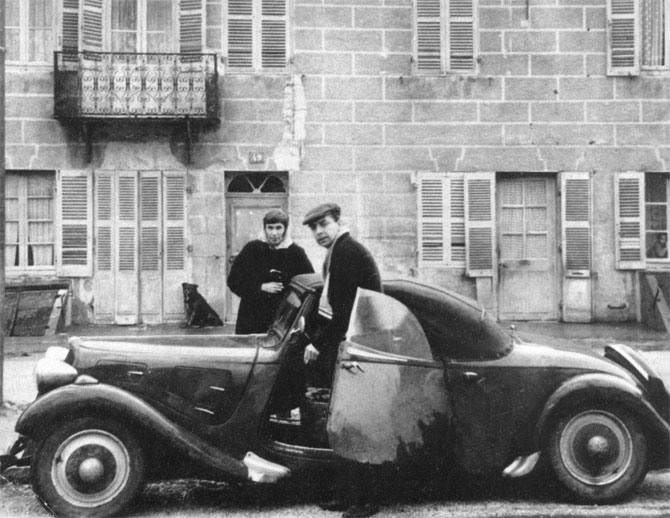

“Well, that wasn’t too bad,” David West muttered as he put the car in gear and pulled out onto the high seacoast road. He was speaking, more or less, to his wife, Vivian, beside him, concerning the ease with which they had just passed the Ventimiglia...