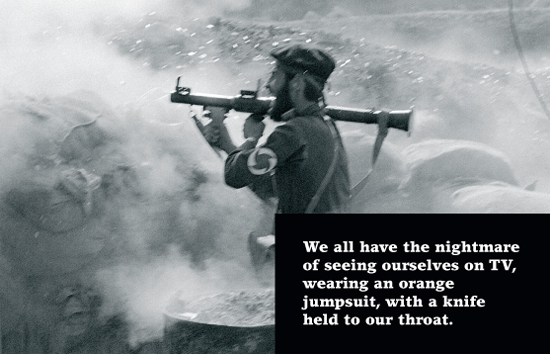

and holds more British and international journalism awards than any other foreign correspondent. He has covered every major event in the region including the Algerian civil war, the Iranian Revolution, the American hostage crisis in Beirut, the Iran-Iraq war, the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, and the American invasion of Iraq. His most recent book, The Great War for Civilization, is a 1,300-page epic eyewitness account of Middle Eastern history, and a best seller in the UK. It’s been translated into eight languages. In short, there aren’t many better guys than Robert Fisk to talk to at a time like, oh, right fucking now. Vice: Has reporting changed a lot since you started 30 years ago? Robert Fisk: Oh yes! Hugely. Technologically, we had no mobiles, no satellite dishes; we had to write on telex machines. I still have one at home. I even did a two-year course in Dublin on how to repair telex machines. Later, I was in Kabul in 1980 during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and my type machine wouldn’t print the letter a. I could repair it and I was still able to send my report on time. Years later, in 1993, I went to Bosnia and I was trying to send a piece by satellite but a signal on my computer just kept saying: “Total disk failure.” I didn’t know how to repair that! And how has this change affected journalism? In my sense, the bigger and more sophisticated the machine became, the weaker journalism became politically. Journalists are no longer independent. They have the technical abilities to do their work, but they are bound to the multinational corporations who back them financially. They also have to deal with local institutions in order to be able to broadcast on foreign grounds. For example, during the Balkans conflict, TV crews had to make a deal with the Serbian government in order to bring their communication systems into the area. Ultimately, this type of agreement influences the truth. If you agree to “cooperate,” you lose your freedom to report both sides of the story accurately. Reporting has become garbage because there is no more street-reporting like what a few of us did the first day we went up to Tripoli: watch a real gun street battle in the heart of the city, without being bothered by the security forces. Have you mostly been welcomed by the local people in the countries you’ve covered? Yes, I’ve been welcomed because people in the Middle East have an open view of foreigners. It’s a Muslim tradition. I have been in the poorest part of Pakistan where they’ve never seen a Westerner before and their first reaction was to bring me into their house and offer me coffee. People there today are less trusting of foreigners and more frightened because of the “war on terror”—a phrase that I hate—but not with me, especially if they know my name. They treat me really carefully and with great courtesy. I went to Tripoli recently and people recognized me because their children read my articles on the internet and they trusted my views.

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ