By Briony Wright, Portrait By Carole Hampshire If Vernon Treweeke weren’t such a decent human being (and a little less of an oddball) he might well have become one of the biggest names in Australian art. He studied alongside close friend Brett Whiteley and, like Brett, moved to London to hone his craft and carve his niche, which would obviously bode well for a career back in Australia. However, unlike Brett, Vernon rejected many of the trappings associated with being a commercial artist and his life took a very different path. Now over 60 and recently retired, Vernon, who’s been referred to as Australia’s reclusive godfather of psychedelic art, is ready to start the next phase of his career and once again hang his paintings on the walls of public galleries.Vice: From what we understand you were just a kid when you got into art.Vernon:When I was 11 my father was killed in a car accident and it was around the same time that I started hanging out with the wrong people and consequently landing myself trouble. As a result I was sent to boarding school—coincidentally the same school Brett Whiteley had recently left. I’d decided that I was going to be an artist by this point and convinced the school to employ an art teacher to tutor me for my leaving certificate. They agreed because they saw I was serious about painting.Right, so how did you come to meet Brett?Well, it just so happened that Brett was expelled from his new school for stealing art materials and so his parents sent him back to my school. It was good for both of us to have someone else around equally interested in painting. We got permission to go on painting expeditions around the Bathurst countryside on Sundays, which was great. We were friends but there was always a competitive element.And what did you do after high school?Well, after high school I went on to Arts school at East Sydney Tech to study Fine Arts essentially. Then I moved to London—there wasn’t much going on in Australia art-wise at the time so London was a logical step. Brett had won a scholarship to move to Europe a few years earlier so we’d lost touch. The first time I went to Cork Gallery though, they told me they didn’t need another Brett Whitely there. That was how I found out he was in London also. So, I tracked him down and we got studios in the same building and resumed our friendship. Just like that. We had a good community of Aussie artists there including Michael Johnson and Laurie Daws.What were you painting while you were in London?I’d say that my paintings had a really distinctly Australian style. We were all influenced by a similar set of Australian artists—William Dobell and Russell Drysdale for instance—and as such there was something similar about all our work. We were all using landscapes as the basis for the paintings and moving into abstraction. One way of identifying the Australian group in London was by the earth tones which dominated a lot of our work.Right, obviously before Ken Done coloured us pastel. Were the English open to Australian artists at that time?Well I think they felt threatened in some ways, particularly by Brett’s success. He was the youngest artist ever to be bought by the Tate gallery.

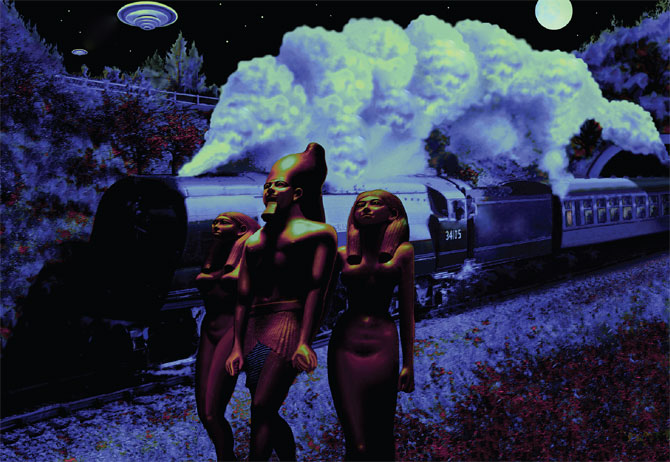

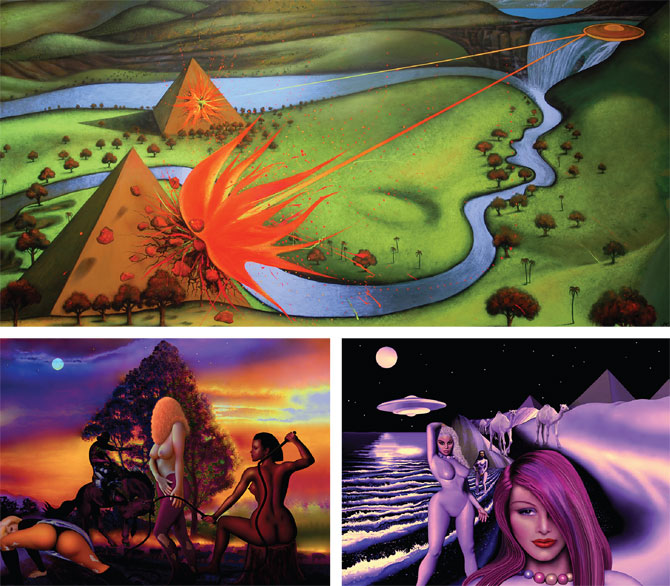

If Vernon Treweeke weren’t such a decent human being (and a little less of an oddball) he might well have become one of the biggest names in Australian art. He studied alongside close friend Brett Whiteley and, like Brett, moved to London to hone his craft and carve his niche, which would obviously bode well for a career back in Australia. However, unlike Brett, Vernon rejected many of the trappings associated with being a commercial artist and his life took a very different path. Now over 60 and recently retired, Vernon, who’s been referred to as Australia’s reclusive godfather of psychedelic art, is ready to start the next phase of his career and once again hang his paintings on the walls of public galleries.Vice: From what we understand you were just a kid when you got into art.Vernon:When I was 11 my father was killed in a car accident and it was around the same time that I started hanging out with the wrong people and consequently landing myself trouble. As a result I was sent to boarding school—coincidentally the same school Brett Whiteley had recently left. I’d decided that I was going to be an artist by this point and convinced the school to employ an art teacher to tutor me for my leaving certificate. They agreed because they saw I was serious about painting.Right, so how did you come to meet Brett?Well, it just so happened that Brett was expelled from his new school for stealing art materials and so his parents sent him back to my school. It was good for both of us to have someone else around equally interested in painting. We got permission to go on painting expeditions around the Bathurst countryside on Sundays, which was great. We were friends but there was always a competitive element.And what did you do after high school?Well, after high school I went on to Arts school at East Sydney Tech to study Fine Arts essentially. Then I moved to London—there wasn’t much going on in Australia art-wise at the time so London was a logical step. Brett had won a scholarship to move to Europe a few years earlier so we’d lost touch. The first time I went to Cork Gallery though, they told me they didn’t need another Brett Whitely there. That was how I found out he was in London also. So, I tracked him down and we got studios in the same building and resumed our friendship. Just like that. We had a good community of Aussie artists there including Michael Johnson and Laurie Daws.What were you painting while you were in London?I’d say that my paintings had a really distinctly Australian style. We were all influenced by a similar set of Australian artists—William Dobell and Russell Drysdale for instance—and as such there was something similar about all our work. We were all using landscapes as the basis for the paintings and moving into abstraction. One way of identifying the Australian group in London was by the earth tones which dominated a lot of our work.Right, obviously before Ken Done coloured us pastel. Were the English open to Australian artists at that time?Well I think they felt threatened in some ways, particularly by Brett’s success. He was the youngest artist ever to be bought by the Tate gallery. What was it like? Were you guys partying a lot?Yeah, it was the swinging 60s and we had a great time. We were definitely in the right place at the right time.How long did you stay in London?Almost five years.And how did being there change your work?Well, I was fortunate to be there because American art had taken over the avant-garde and was all coming to Europe via London, so we were the first to see everything. We were really right in the centre of it all. When I came back to Australia, I felt like I’d time travelled. I was surprised at how isolated it seemed to be. Nobody had ever seen any American art. Back in Sydney some friends and I put on the first international art show at Central Street, a gallery we started ourselves with the purpose of introducing what was happening outside of the country.And how did your work develop around that time?Inspired by what I’d learnt in London it became more figurative but it was disguised in a sense because I created giant kaleidoscope-like images on silk screens.Your work is often described as psychedelic but I think some of it could also be filed under surreal. How does that sit with you?Well in the early days, LSD was influencing everything and the term “psychedelic” was thrown around so loosely. I just happened to put on the first psychedelic show here in Australia in Central Street in 1967 and it kind of stuck.And what did you do for that show?More or less what I’m still doing now; I used ultra-violet light and fluorescent paint so the works effectively turn on; they glow in the dark. That’s still how I work predominantly but now I make the pieces three dimensional and you’re meant to look at them through 3D glasses.

What was it like? Were you guys partying a lot?Yeah, it was the swinging 60s and we had a great time. We were definitely in the right place at the right time.How long did you stay in London?Almost five years.And how did being there change your work?Well, I was fortunate to be there because American art had taken over the avant-garde and was all coming to Europe via London, so we were the first to see everything. We were really right in the centre of it all. When I came back to Australia, I felt like I’d time travelled. I was surprised at how isolated it seemed to be. Nobody had ever seen any American art. Back in Sydney some friends and I put on the first international art show at Central Street, a gallery we started ourselves with the purpose of introducing what was happening outside of the country.And how did your work develop around that time?Inspired by what I’d learnt in London it became more figurative but it was disguised in a sense because I created giant kaleidoscope-like images on silk screens.Your work is often described as psychedelic but I think some of it could also be filed under surreal. How does that sit with you?Well in the early days, LSD was influencing everything and the term “psychedelic” was thrown around so loosely. I just happened to put on the first psychedelic show here in Australia in Central Street in 1967 and it kind of stuck.And what did you do for that show?More or less what I’m still doing now; I used ultra-violet light and fluorescent paint so the works effectively turn on; they glow in the dark. That’s still how I work predominantly but now I make the pieces three dimensional and you’re meant to look at them through 3D glasses. Really, 3D is going crazy right now. And so you paint with that in mind obviously?Yes, it’s basically like painting and sculpting at the same time. Or, otherwise, sculpting with paint. I wear the glasses as I paint and I’m aware of the sculptural form at the same time as the flat image I’m working on. I started doing that in 1966 after being influenced by the psychedelic nightclubs in London—the U.F.O club for instance where Pink Floyd used to perform.So you were doing really well but then, quite suddenly, you dropped out of the art scene altogether. What happened?Well yeah, I dropped out and joined the alternative life, I guess. I found out that people were buying my paintings—not necessarily because they liked them but because they were a tax deductable purchase—a case of capitalist corruption basically. I’m a Socialist by nature and politically a member of the Labour party and this just seemed really wrong to me. Why should wealthy people be able to avoid paying tax by buying art and why should art be treated like a charity? The whole thing just disturbed me. Of course it made some artists fabulously rich but I decided I was done.So what did you do instead?Well, I moved to Nimbin, organised the largest Aquarius festival and started a commune on a 2,000 acre property at Tuntable Falls in Northern New South Wales. Then I found out my mother was very ill so moved to the Blue Mountains to be with her and we just ended up staying there. We bought a house and had kids and so I got a job on the railways and was there for 28 years until I retired just recently.Wow, did you enjoy it?I didn’t mind it. I worked with a good group of working class people—I liked them and I liked working, but it did mean I did less painting. I’ve had to wait to turn 65 and retire to get right back into painting. I mean I’ve always painted for family and friends and was commissioned to do a few murals along the train lines but I could have been doing so much more.

Really, 3D is going crazy right now. And so you paint with that in mind obviously?Yes, it’s basically like painting and sculpting at the same time. Or, otherwise, sculpting with paint. I wear the glasses as I paint and I’m aware of the sculptural form at the same time as the flat image I’m working on. I started doing that in 1966 after being influenced by the psychedelic nightclubs in London—the U.F.O club for instance where Pink Floyd used to perform.So you were doing really well but then, quite suddenly, you dropped out of the art scene altogether. What happened?Well yeah, I dropped out and joined the alternative life, I guess. I found out that people were buying my paintings—not necessarily because they liked them but because they were a tax deductable purchase—a case of capitalist corruption basically. I’m a Socialist by nature and politically a member of the Labour party and this just seemed really wrong to me. Why should wealthy people be able to avoid paying tax by buying art and why should art be treated like a charity? The whole thing just disturbed me. Of course it made some artists fabulously rich but I decided I was done.So what did you do instead?Well, I moved to Nimbin, organised the largest Aquarius festival and started a commune on a 2,000 acre property at Tuntable Falls in Northern New South Wales. Then I found out my mother was very ill so moved to the Blue Mountains to be with her and we just ended up staying there. We bought a house and had kids and so I got a job on the railways and was there for 28 years until I retired just recently.Wow, did you enjoy it?I didn’t mind it. I worked with a good group of working class people—I liked them and I liked working, but it did mean I did less painting. I’ve had to wait to turn 65 and retire to get right back into painting. I mean I’ve always painted for family and friends and was commissioned to do a few murals along the train lines but I could have been doing so much more. So it changed the reasons that you painted—more for yourself and less for commercial reasons. So back to the Aquarius festival, was it good times?It was great. We were inspired to put the festival on when professor Aleeg, the world’s leading ecologist, did a world tour to announce his findings that we only had 30 years left to turn the environment around. That was in 1970 and the media took no notice at all. We all took him seriously and it inspired us to put on this festival, which was essentially about how to live without polluting the planet.And some of the people who went liked it so much they made Nimbin their new home right?At the end of the ten-day festival we discovered that Nimbin was a semi-ghost town—there were literally three stores open and everything else was for sale, so we were buying the shops for between $500 and $1,000. We were looking for somewhere to build a festival town but we found one already made. It was great.Why had it been abandoned?Well, that’s an interesting story. The town’s original inhabitants were members of Aboriginal tribes and when white people took over, the tribes supposedly cursed the place and as a result people left. Prior to the festival, we contacted the Aboriginal chief, who was in hospital, and he offered to lift the curse for us. So, the couple hundred of us who were already working there on the festival site were gathered one night on a large paddock where a ring of fires had been set up. They divided us into two groups—girls and guys—and sent us one hundred metres from the fire where we had to wait until the ceremony was complete. We weren’t allowed to witness what was happening but we could hear the didgeridoos and clap sticks and then after about 20 minutes we were called back and advised that the curse had been lifted.Amazing, just like that. That’s a great story. So you brought life back to Nimbin and then moved to the Blue Mountains. How has living there affected your work?Well, the mountains seem to attract a lot of astrologers and UFO watchers and many people claim to have seen them up here. I haven’t seen anything yet but I guess I think about it a lot because space ships or UFOs have appeared in a lot of my work. Also, my wife was born in Egypt so you’ll see things like camels and pyramids popping up in my work also. Other times I’ll be thinking of a song and paint something in the lyrics. It’s all quite random really.It’s great though. You had an exhibition in 2003, your first in 30 years. Do you have any more planned?Yes I have one coming up in Sydney in June at Carriageworks. I have a feeling that will be a big one.

So it changed the reasons that you painted—more for yourself and less for commercial reasons. So back to the Aquarius festival, was it good times?It was great. We were inspired to put the festival on when professor Aleeg, the world’s leading ecologist, did a world tour to announce his findings that we only had 30 years left to turn the environment around. That was in 1970 and the media took no notice at all. We all took him seriously and it inspired us to put on this festival, which was essentially about how to live without polluting the planet.And some of the people who went liked it so much they made Nimbin their new home right?At the end of the ten-day festival we discovered that Nimbin was a semi-ghost town—there were literally three stores open and everything else was for sale, so we were buying the shops for between $500 and $1,000. We were looking for somewhere to build a festival town but we found one already made. It was great.Why had it been abandoned?Well, that’s an interesting story. The town’s original inhabitants were members of Aboriginal tribes and when white people took over, the tribes supposedly cursed the place and as a result people left. Prior to the festival, we contacted the Aboriginal chief, who was in hospital, and he offered to lift the curse for us. So, the couple hundred of us who were already working there on the festival site were gathered one night on a large paddock where a ring of fires had been set up. They divided us into two groups—girls and guys—and sent us one hundred metres from the fire where we had to wait until the ceremony was complete. We weren’t allowed to witness what was happening but we could hear the didgeridoos and clap sticks and then after about 20 minutes we were called back and advised that the curse had been lifted.Amazing, just like that. That’s a great story. So you brought life back to Nimbin and then moved to the Blue Mountains. How has living there affected your work?Well, the mountains seem to attract a lot of astrologers and UFO watchers and many people claim to have seen them up here. I haven’t seen anything yet but I guess I think about it a lot because space ships or UFOs have appeared in a lot of my work. Also, my wife was born in Egypt so you’ll see things like camels and pyramids popping up in my work also. Other times I’ll be thinking of a song and paint something in the lyrics. It’s all quite random really.It’s great though. You had an exhibition in 2003, your first in 30 years. Do you have any more planned?Yes I have one coming up in Sydney in June at Carriageworks. I have a feeling that will be a big one.

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ