ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

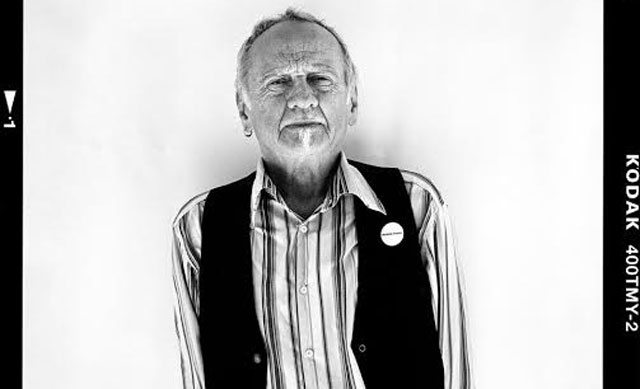

Ritchie Yorke: Well it was 1963 and I’d gotten a job as a copywriter at a radio station in Toowoomba. A crucial part of the deal for me was that I had my own rock ‘n’ roll show on Saturday nights. At the time I was on the mailing list with Motown Records so every couple of weeks I would get a package with all the latest singles they had released.On one of those days I received a record called "Fingertips Pt 2" by this guy called Little Stevie Wonder. It turned out that he was a 12-year-old blind kid. It became an instant hit in America and went to number one. I was impressed, not only by that, but because this was the most unbelievable record I’d ever heard in my life—I couldn’t wait to play it on the air. On the following Monday morning I was called into the program manager's office where he told me they weren’t too impressed with the sort of music I was playing. They didn’t want any of this “nigger music” or they would kick me out.The following Saturday night I locked myself in the studio and played it again, only this time I played it eight times in a row before they got down there and fired me—that was the end of that job!What made you do that?

Well I felt a line needed to be drawn. This was music history! And it was absolutely brilliant music.Was there much black music being played at that time?

Hardly any at all. Australia in 1963 was basically a black music free zone. They didn’t touch anything that remotely resembled rhythm and blues, especially the big city stations. It was sad but that’s the way it was here for a long time.

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

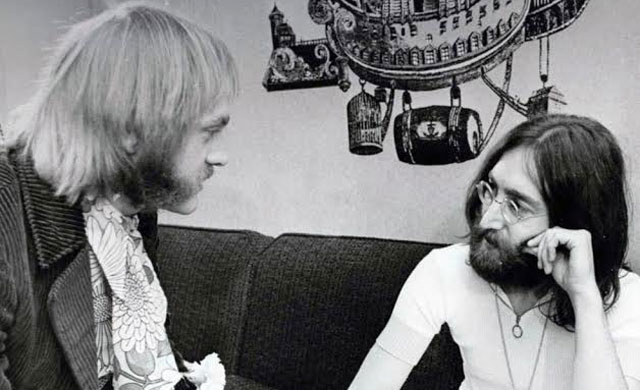

I met John in ’68 while working for The Globe and Mail in Toronto, which is Canada’s national newspaper. I was their first full-time rock writer. I used to make long weekend trips to London. I would head over on the Friday and do interviews, then fly back on the Monday or Tuesday. I met John once or twice and discovered that we had a lot of things in common and I really liked what he was trying to do.John was emerging in his own right. It was the early days of John and Yoko together and John was anxious to make his own statement. I was very impressed by what he was trying to say—I joined in his corner and became one of the people he could call on to help spread his word.How long after meeting him were you asked to become the Peace Envoy for the “War Is Over! (if you want it)” campaign?

Probably about a year. That came after we had already worked on a few peace/music projects together. I became John and Yoko's “go-to man” in Canada. It was a very fortunate experience for me. John couldn’t get into the US at that time because he was busted a few months earlier in London for possession of a piece of hash planted in his flat by a crooked cop.

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

I certainly do. I was living in a little country town called Erin, about an hour outside of Toronto, when I got a phone call. It was about 11 o’clock at night and a friend had heard a radio news flash saying that John Lennon had been shot. I don’t think I’ve ever been quite the same since. I think a part of all of us died in that moment—the caring part. How can a man involved in peace be shot?!

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

Probably the night I introduced them at The Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto. To go out on stage when everything is pitch black, have this little spotlight come on you and then hear the roar of 18,000 people who are just dying for the show to begin. When I announced it—“Ladies and Gentlemen, the greatest rock ‘n’ roll band in the world…. LED ZEPPELIN”—and the whole crowd started screaming, it was just this burst of energy.You also worked with Jimi Hendrix a number of times and were one of the last people to interview him before his death. What was it like to work with him?

I had the pleasure of interviewing Jimi a few times, including what I actually think was his last interview. During that interview Jimi revealed to me that he was going to go to Memphis, Egypt to “meet his maker”. I rather flippantly said, “Well, if and when you meet him, call me and I’ll be right over”, which is sort of a pretty slack ass response, but at the time I didn’t think he was for real. Looking back, it was probably a premonition. I recall by that stage, after interviewing him a few times, he was getting a bit scattered. He was losing it.

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

Yeah. Jimi went through a lot of different stages. When he finally cracked it out of England with his first album Are You Experienced he was thrilled to death. He’d been a studio musician for years and on tour with a lot of black acts that weren’t treated very nicely: southern states in the US that had segregated buses, restaurants, and washrooms—just awful stuff. He was happy at times but in the latter years he seemed to be what you would politely call “confused”.Was his drug use quite severe at that time?

I gathered so but I never did drugs with him. I’d read and heard he was pretty into it and of course he eventually OD’d.My other connection with Jimi was when he played in Toronto. He’d flown in from Detroit where he’d had a gig the night before but was busted at customs when he arrived in Canada. They opened his suitcase and found a bag of marijuana inside. They charged him right away and I went to court that afternoon and acted as a character witness for him. I had to tell the judge that he was an internationally known musician who was playing for 14,000 paying customers at the Maple Leaf Gardens that night, and if they didn’t let him go there was going to be a riot. He was incredibly grateful to me for supporting him at that point and he gave me his hat as a gesture of his gratitude. I still have it as part of my archives. He was a very nice guy, very humble to talk to and Jesus—he could play a guitar!

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

I think back then music was made from the heart. People made it cause they felt it and they needed to. It was much more experimental—it was more about getting a groove happening and just going for it. There’s a lot more restraint on everything now. Nowadays it seems to be driven by money. Money was obviously a factor back then as well, but the record companies were run by great music men that released the music they felt good about. The people running the labels today tend to be accountants or lawyers. I think there’s still some people that care about the music but it’s become much more of a business now—they play it safe rather than take risks.What do I think about today’s music? It’s difficult. There’s always great music out there, I just think it’s become less evident. There’s less of it on the radio because stations have boxed themselves into a narrow little format driven by an approach that doesn’t allow creativity. I think there’s much more concern with fashion and style rather than substance. I’m about the quality of the music and always have been. I’m not against the fashion as such but I don’t think it should drive the forward approach to music. Also, nowadays the A&R departments of record companies are driven by television talent shows. They're copying other people so you’re never going to get much originality. It’s a pity because the music is really suffering.

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

It’s hard to pinpoint just one. Ok: I guess sitting in Criteria Studios in Miami, Florida in 1969 and experiencing the Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin, recording tracks with Skydog Allman on guitar, The Sweet Inspirations singing backing vocals, and the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section playing as she recorded four titles in an afternoon. That was quite extraordinary; the entire control room—the engineer, the producer, the arranger, and myself—were all in tears. Just how she sang and the atmosphere in the air—unbelievable. The emotion was so powerful!Another was the night I introduced Frank Zappa at the Rockpile Club—Toronto's version of the Fillmore. In the course of his set, during an extended improv break, Frank came back out on stage and peed all over the front row of the audience—literally pulled his dick out and pissed on them! No one complained. They all wore it in the literal sense of the word. [Chuckles]A lot of people like the controversy aspect of rock and tend to write about what happened backstage and the girls that the bands were screwing. I tended to write about the music. I felt the music deserved that respect—I always felt you should be honest to your source.What are you currently working on?

I’ve been sifting through my archives and realized just how much I have, so I’m working with a television production company on an international documentary and transmedia project. We’re using my memorabilia and insider stories to tell a bigger story of the music and the times. I’ve also recently contributed to a new coffee table book by Hardie Grantcalled “Rock Country”.And lastly, any advice for aspiring music journos?

I guess firstly, be true to yourself—write about what you believe. Try and see through the industry bullshit, cause there’s a lot of it. You've got to evolve beyond just the current scene. Try and find out more about where the music came from.They say journalism is a dying art, that there’s not much opportunity to get out there and find a place for yourself. But you've got to persevere and keep trying. Marvin Gaye used to urge us all to “keep on keepin’ on.” I guess that’s pretty close to the truth.Follow Bradley on Twitter: @BradleyScottAusFor more by the author:Tim Page's Vietnam War20 Years In War Zones With Jack PiconeAt War With Stephen Dupont