FYI.

This story is over 5 years old.

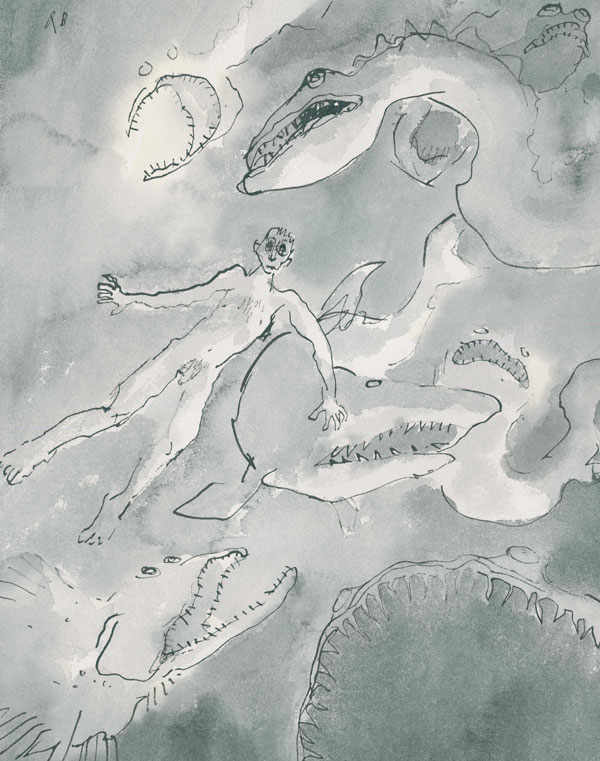

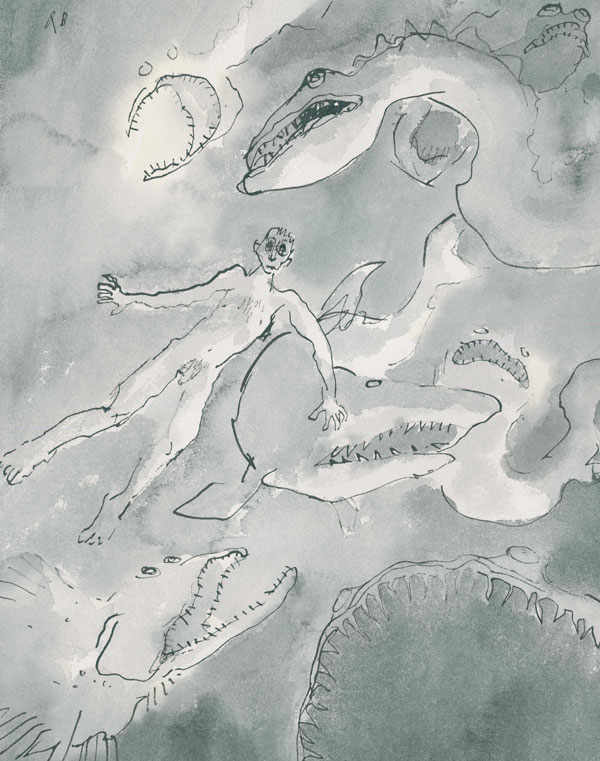

In Cretaceous Seas

I tend to flip from OK insomnia to bad insomnia depending on how things in my life are going, and this story came out of a stretch of insomnia as bad as I've had in a while. I'd been struggling with another story for some months by that point, and woke...