If Stephen Shore were known just for the iconic photos he shot as a teenager at Warhol’s original Silver Factory, he’d probably still get a place in the history of photography. But galvanized by a road trip from Manhattan to Amarillo, Texas, in 1972, Shore went on to pioneer the use of color in fine-art photography. Over the intervening years, his photos have also documented America and Americans in a way that presaged the straight-on deadpan vibe of much current image-making—this includes streetscapes and architecture shot to reveal them as abandoned film sets, and cryptic vérité portraits of people he meets.

In 1998, Shore wrote a book that’s been handed around by photographers of my acquaintance ever since. The Nature of Photographs is an illuminating meditation on the basic assumptions we have and make while looking at photos. It has the power to shift your own perceptions with one read.

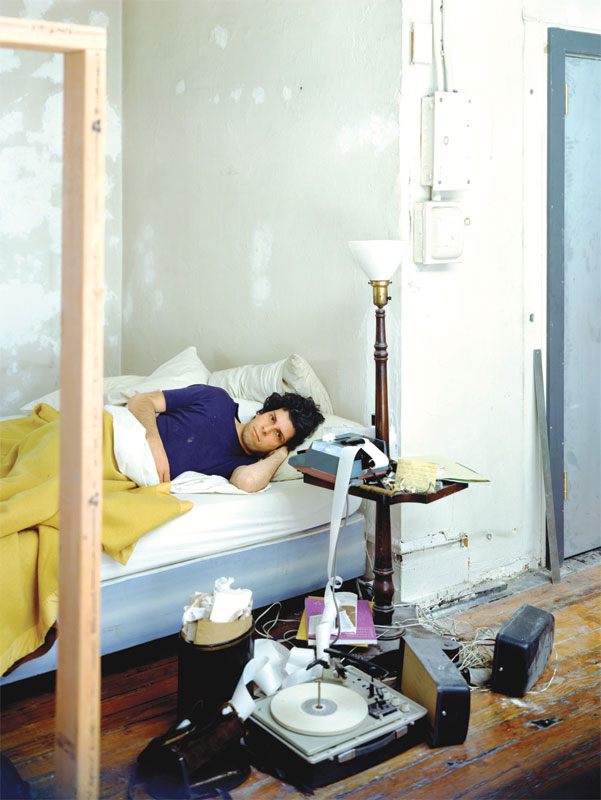

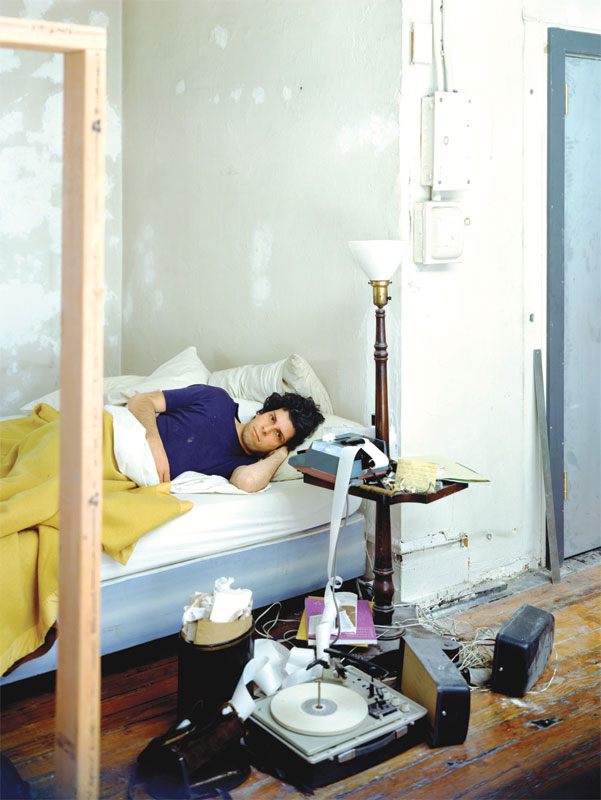

Since 1982, Stephen Shore has been the director of the photography department at Bard College. Self-portrait, New York, New York, March 20, 1976Vice: Do you use The Nature of Photographs in your teaching?

Self-portrait, New York, New York, March 20, 1976Vice: Do you use The Nature of Photographs in your teaching?

Stephen Shore: Actually, The Nature of Photographs grew out of a class that I had taught called “Photographic Seeing.” At first I was using John Szarkowski’s book The Photographer’s Eye as a text. But there was one chapter that didn’t fit with the way I wanted to teach, so I wrote a new one. Then I decided I had enough material to do a book. But yes, I still use it now, and I find that my students are very receptive. Are you surprised that it’s become such a must-read among younger photographers?

I’m not aware of that. Unless somebody tells me, there’s no real way for me to know what effect it has. It’s delightful for me to hear that it’s getting that response. It’s so rigorous in its logic, so I wonder if it’s hard teaching a student whose reasons for being a photographer might be at odds with your own?

Their approach and style can be radically different and it doesn’t pose a problem. But let me qualify that. In the early 80s, when I first came to Bard, most of the photography programs around the country emphasized manipulated photography. Photography as a kind of printmaking—collaging, painting on photographs, sewing on photographs, that kind of thing. The photography faculty at Bard decided we were going to emphasize straight photography—that we would simply take an aesthetic stance and that we wouldn’t try to satisfy everyone. There were plenty of other schools to go to if people were interested in the manipulated image. But within the straight approach there’s still a huge range, including performative, snapshot… a huge range of possibilities. We made that distinction early on, but even then some of the students in their senior year veer off from it, and in using Photoshop enter more into the printmaking realm. I don’t find there’s any problem. I feel my job is to help the student find their voice. Does teaching affect your own work?

Definitely. If I have ten people in a class, I have to begin to think like ten different people. I’m trying to lead them individually to their next step as artists. And so I find myself, as I go out into the world with a camera, having more visual ideas than if I hadn’t been teaching. Ideas that may seem not in line with what people think of as my style. For the past five years, my main project has been a series of books using print-on-demand technology. These books often go in very different directions because I can explore an idea that I might want to spend one day on, that I’m not interested in spending a year on. And I think the genesis of some of this was the mental exercise of teaching different people. Digital cameras had to have helped.

I think digital made it easier. I guess I could have done it with film. But it seemed to flow with digital. There’s something light and spontaneous in the touch of digital sometimes. When did you first start using it?

For work that I’m really focused on, about six years ago. I imagine you use it for fashion editorials.

That’s all I’m using now for commercial work. It flows so much better. What cameras do you have for that?

I use different ones on the job. I rent them. Last week I did a job and I was using a Nikon D3. But I use a Canon Mark III sometimes, or a 4x5 camera with a Leaf back. It really depends on the situation, what the needs are. Fifteen years ago when you were doing work like this you might go Polaroid first, and when the Polaroid got approved by everyone then do the shot. That’s fine if it’s a tabletop still life. But for example, in January I did a Nike campaign using athlete models who were running. I needed to get the motion of them running, get their legs in a visually interesting configuration, and at the same time have three different styles of running shoes clearly visible. I had to have them run over and over again. If I was doing this and made a Polaroid, and the art director and the client all approved, now I would have to put film in the camera and try to re-create it. It would be almost impossible. This way they look at the image on a computer and they say, “Yes, that’s the one,” and that’s it. In your fine-art work the concept of a photograph is more important than its need to also be an aesthetic object made by “authentic” means of film negative and a darkroom. Digital could have hit that mark.

I don’t really have an explanation for why I didn’t explore it sooner. I remember that one of my first digital cameras was a Casio Exilim, which was then about the size of a PalmPilot. After 30 years of using an 8x10, the idea of a camera that was about a quarter of the size of my exposure meter had a certain attraction. But actually I’ve always been interested in commonly available technology and processes that are very accessible. So I’m not sure why I didn’t use digital sooner. I read an article wherein you spoke about the economy of digital versus analog.

There is some relation between the cost of taking a picture and the attention the photographer pays to the picture. With an 8x10 camera, simply because it costs, say, $35 or $40 for a sheet of film processing and the contact print, the picture is going to be well considered. Because the digital picture is free, what I find is a two-sided phenomenon. The positive side is that there’s less restraint and greater potential for spontaneity. The downside is that there’s more work that’s made that isn’t particularly considered at all. The camera itself doesn’t require that. However, if somebody wants to use the camera with very consciously directed attention, it does that too. Your most iconic pictures were made with view cameras, either 4x5 or 8x10. Given what you just said, does it follow that those images were the only version of the shot?

Yes, absolutely. And that’s where the economy came in. I realized that I couldn’t try to limit myself by only taking pictures that I knew beforehand were going to be good. Because then I would only take safe pictures, that way I wouldn’t learn anything. What’s the point? So the way I made this process that I loved financially feasible was to decide that I wasn’t going to take two of anything. I don’t mean not bracket, I mean exactly what you said—not even two views. What it forced me to do was to decide what I wanted.Lee Cramer, Bel Air, Maryland, 1983In the photo diaries of your road trips in the 70s, how did you get shots of, say, your breakfast in a diner with such a big camera?

With the photo of pancakes, I asked the waitress if she minded if I brought out a big camera so I could get a picture. She didn’t, but I wound up having to stand on a chair, and the camera was on a tripod seven feet in the air. Did being so conspicuous affect the photos?

The year before American Surfaces, in ’71, I was using a small 35 mm. I had hair to my shoulders and looked sort of like a hippie, and every now and then I’d be photographing in a neighborhood and some resident would call the police. The cops would ask me, “What are you doing?” and every now and then I was told to get out of the neighborhood. Once I started using a view camera that never happened. That the camera is so conspicuous gives it even greater license. The extreme examples of this are two works from a series that I’ve never shown before—New York City photographs that I did with an 8x10 of people interacting on the street. And I’d never before been more invisible. I would stand at 72nd and Broadway or 52nd and 5th with this big camera, and people would just walk around me. I photographed people at crosswalks, people hailing a cab, and I’d be six feet away from them taking their picture with an 8x10 camera, and no one would be paying any attention to me. But all those landscapes devoid of humans were because you wanted fewer people around to ask you what you were up to?

Part of it was technical. My exposures were typically a half or a quarter of a second, so if I had a person in the shot they had to be either posing for me or stopped at a crosswalk. But I don’t want to say that it was simply technical, because I chose the tools. If having the streets full of people was that important to me and were an essential part of what I was trying to do and I couldn’t have accomplished it with those tools, I would have used different tools. There’s also another factor that those of us who grew up in New York might not recognize. If you go to some intersection in Ashland, Wisconsin, and set up a camera, if you wanted a person in the picture, you’d have to wait. In most of these towns, the streets are not full of people the way they are outside our windows in New York. I now live in a small town. Consequently, those photos have a lot more meaning to me now. But you’ve done such compelling portraits, too. Have you ever consciously shot a series of portraits?

Not really. In American Surfaces, I’d say about a fifth of the pictures are portraits, and that was probably the most extensive. Although my Warhol pictures are pictures of people, they’re not necessarily portraits. There were periods in the 70s when I would come back to portraits. I did a number in Fort Worth in ’76. A few of them have been published. And then I photographed almost every member of the Yankees in ’78. But for a lot of the time in the 70s, I had particular cultural questions on my mind and also particular formal questions that just didn’t relate to portraiture. Critics sometimes refer to your landscapes as “portraits.” But isn’t there some ineffable quality to a human portrait that can’t be applied to objects?

That’s a really good question, and I don’t think there’s a simple answer. Whenever you see a person in a picture, your response is different. It’s not like looking at a mailbox or a lamppost. There’s the attraction of the eye, there’s the focusing on it, and a chain of associations that are all very different. For American Surfaces, I asked everyone before I photographed, “Can I take your picture?” And I was thinking about not just their expressions but what their clothes were and what their backgrounds were, information about their heritage. It fit into a kind of cultural nexus. I think that that work in particular integrated the portrait maybe more successfully than at any other time for me. So what about the description of your landscapes as portraits?

I would say they feel that way because maybe there’s a sense in a portrait of paying very focused attention and respect to someone. That the photographer is showing some respect and is looking carefully at a person. The viewer may pick up that same quality in looking at a building or looking at a street. It’s as if you entered into the same deal with the building as you would a person of whom you’re making a portrait. That quality runs all through your work. I wonder how intentional it is. Or are we getting into quantum science, where intentionality has the power to transform the physical?

That’s exactly the point where my work finally wound up in the 80s when I was doing actual natural landscapes. That is what I was exploring—how responsive this very mechanical medium can be to subtle shifts in the state of mind of the artist. There’s a recurring theme in The Nature of Photographs. You advocate developing a closer relationship with all of our senses—paying more attention to how they work and training ourselves to better monitor what they’re trying to tell us. Your best pictures are examples of just that.

A photograph can do many things at once. I can be exploring culture or I can be making decisions about what street to photograph to give a taste of this town or this age. At the same time, I can explore the medium formally, explore how the structure of a picture may give a taste of an age, how perception works, and how a photograph plays with it. I can also explore what you were saying, that sometimes the most mundane subject matter is the most telling because what gives the picture charge isn’t the cultural charge of the content as much as the awareness of the senses and the awareness of perception giving it a kind of visual resonance. It’s like those days or moments when maybe your mind gets a little quieter and space becomes more tangible, textures and colors become more vivid.Sneden’s Landing, New York, July, 1972Do you think the brain switches between different states of optical perception, like a camera?

Yes, it’s one of the things I learned from the process of photography. Let me give an example. I think it’s absolutely typical that you could leave your house and have a certain walk to a café every day and not really pay attention to what’s around you, but if you put a camera on your shoulder, all of a sudden you do. What can I learn from that? To address it in a different way, when I was photographing the Yankees I would see these people who were performing mind-boggling feats of attention. I’ve been going to baseball games since I was six, but from the stands there’s no way to experience what a major-league fastball looks like from the batter’s perspective. At spring training in Fort Lauderdale, I was able to stand essentially where the umpire was and watch these pitches being thrown. That anyone can even hit a fastball is an amazing feat of attention and coordination. But if you talk to them, they’ll say that when they’re really in the flow of it, they’re watching the rotation of the stitches on the ball. Yet these same people who are able to perform this so well would at four in the afternoon go to a bar called Trader Jack’s and try to pick up young girls and forget the state of mind that they had achieved that even allowed them to see the ball. They weren’t carrying the lesson of that into the rest of their lives. I wonder why we don’t go through our lives paying closer attention, and what would accrue from doing that. In the 90s you published a book of photographs called Essex County. It featured compelling and, I have to say, strange images of trees, flora, etc. It seemed almost a break from the earlier work, but in some hard-to-pin-down way.

There are a number of things I could say to that. One thing is that I take pictures to solve problems, visual problems, and the picture is the byproduct of that. I find that when I work everything out [in the problem], I don’t want to repeat myself. It’s my nature to keep trying to push myself into new directions. That’s one of the reasons that particular work looks so different from what I’d done before. I’d worked out a number of problems in my streetscapes of the 70s and my landscapes of the 80s, and by the time I got to this body of work my concern was for seeing with a kind of deeper resonance. I want to present you with four of your best-known portraits and have you tell me something about their circumstances. The first is New York City, New York, September–October 1972, a shot of Henry Geldzahler.

It was at a party. I had known Henry since the mid-60s. I think there’s something delightful about him eating the apple. The book it’s in, American Surfaces, began as a cross-country trip, and I photographed different categories of things repeatedly, including everyone I met. I continued this after I got back to my home in the city. I never identified the people, but it’s a mixture of very close friends and someone I would run into in a bus depot in Oklahoma City, or a gas-station attendant. A whole range of people, whether or not identified. There’s Senator Javits, the Earl of Gowrie, and the great avant-garde film critic P. Adams Sitney. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, July, 1972.

This is someone I met, I think, in a bus depot. The Trailways bus depot in Oklahoma City. I just thought he was a wonderful character. Self-Portrait, New York, NY, 3/20/76.

The self-portrait is set up. I was looking at things like the tape coming from the adding machine. I was thinking of these little details and how to arrange it. But I can’t remember what else was on my mind. Lee Cramer, Bel Air, Maryland, 1983.

It was my father-in-law in his kitchen. I’ll say this about portraits in general that I find very interesting: Facial expressions and signs that we’re culturally attuned to pick up on read as particular emotions. There is also the problem that facial expressions flow in time and, taken out of the context of their time by a still photograph, can mean something different than they actually are. Nonetheless, we’re left with this result that we read emotion and experience into. A wonderful example is a book of portraits made by the photographer Robert Lyons of both perpetrators and surviving victims of the Rwandan genocide. They are not titled; they’re indexed in the back of the book. They’re faces of men that have a look in their eye of depth of experience and wisdom and compassion… visual symbols we read as those things. Then in the back you read that this person ordered the death of 17 people. A wonderful photographer named Tod Papageorge, who is a good friend of mine, photographed my wedding. It was in California and he came out and photographed people that he had never met before that day. And in his pictures every single one of these people is shown in their essence. So on the one hand we know there is something deeply fictive about a portrait and yet on the other there’s this result where I see Tod’s penetrating insight in understanding people. I also feel that the picture of my father-in-law does communicate something about his state of mind. And that is the conundrum of the portrait.Sandusky, Ohio, July, 1972New York City, New York, September–October, 1972Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, July, 1972Toledo, Ohio, July, 1972Stanley Marsh and John Reinhardt, Amarillo, Texas, February 15, 1975

Advertisement

Stephen Shore: Actually, The Nature of Photographs grew out of a class that I had taught called “Photographic Seeing.” At first I was using John Szarkowski’s book The Photographer’s Eye as a text. But there was one chapter that didn’t fit with the way I wanted to teach, so I wrote a new one. Then I decided I had enough material to do a book. But yes, I still use it now, and I find that my students are very receptive. Are you surprised that it’s become such a must-read among younger photographers?

I’m not aware of that. Unless somebody tells me, there’s no real way for me to know what effect it has. It’s delightful for me to hear that it’s getting that response. It’s so rigorous in its logic, so I wonder if it’s hard teaching a student whose reasons for being a photographer might be at odds with your own?

Their approach and style can be radically different and it doesn’t pose a problem. But let me qualify that. In the early 80s, when I first came to Bard, most of the photography programs around the country emphasized manipulated photography. Photography as a kind of printmaking—collaging, painting on photographs, sewing on photographs, that kind of thing. The photography faculty at Bard decided we were going to emphasize straight photography—that we would simply take an aesthetic stance and that we wouldn’t try to satisfy everyone. There were plenty of other schools to go to if people were interested in the manipulated image. But within the straight approach there’s still a huge range, including performative, snapshot… a huge range of possibilities. We made that distinction early on, but even then some of the students in their senior year veer off from it, and in using Photoshop enter more into the printmaking realm. I don’t find there’s any problem. I feel my job is to help the student find their voice. Does teaching affect your own work?

Definitely. If I have ten people in a class, I have to begin to think like ten different people. I’m trying to lead them individually to their next step as artists. And so I find myself, as I go out into the world with a camera, having more visual ideas than if I hadn’t been teaching. Ideas that may seem not in line with what people think of as my style. For the past five years, my main project has been a series of books using print-on-demand technology. These books often go in very different directions because I can explore an idea that I might want to spend one day on, that I’m not interested in spending a year on. And I think the genesis of some of this was the mental exercise of teaching different people. Digital cameras had to have helped.

I think digital made it easier. I guess I could have done it with film. But it seemed to flow with digital. There’s something light and spontaneous in the touch of digital sometimes. When did you first start using it?

For work that I’m really focused on, about six years ago. I imagine you use it for fashion editorials.

That’s all I’m using now for commercial work. It flows so much better. What cameras do you have for that?

I use different ones on the job. I rent them. Last week I did a job and I was using a Nikon D3. But I use a Canon Mark III sometimes, or a 4x5 camera with a Leaf back. It really depends on the situation, what the needs are. Fifteen years ago when you were doing work like this you might go Polaroid first, and when the Polaroid got approved by everyone then do the shot. That’s fine if it’s a tabletop still life. But for example, in January I did a Nike campaign using athlete models who were running. I needed to get the motion of them running, get their legs in a visually interesting configuration, and at the same time have three different styles of running shoes clearly visible. I had to have them run over and over again. If I was doing this and made a Polaroid, and the art director and the client all approved, now I would have to put film in the camera and try to re-create it. It would be almost impossible. This way they look at the image on a computer and they say, “Yes, that’s the one,” and that’s it. In your fine-art work the concept of a photograph is more important than its need to also be an aesthetic object made by “authentic” means of film negative and a darkroom. Digital could have hit that mark.

I don’t really have an explanation for why I didn’t explore it sooner. I remember that one of my first digital cameras was a Casio Exilim, which was then about the size of a PalmPilot. After 30 years of using an 8x10, the idea of a camera that was about a quarter of the size of my exposure meter had a certain attraction. But actually I’ve always been interested in commonly available technology and processes that are very accessible. So I’m not sure why I didn’t use digital sooner. I read an article wherein you spoke about the economy of digital versus analog.

There is some relation between the cost of taking a picture and the attention the photographer pays to the picture. With an 8x10 camera, simply because it costs, say, $35 or $40 for a sheet of film processing and the contact print, the picture is going to be well considered. Because the digital picture is free, what I find is a two-sided phenomenon. The positive side is that there’s less restraint and greater potential for spontaneity. The downside is that there’s more work that’s made that isn’t particularly considered at all. The camera itself doesn’t require that. However, if somebody wants to use the camera with very consciously directed attention, it does that too. Your most iconic pictures were made with view cameras, either 4x5 or 8x10. Given what you just said, does it follow that those images were the only version of the shot?

Yes, absolutely. And that’s where the economy came in. I realized that I couldn’t try to limit myself by only taking pictures that I knew beforehand were going to be good. Because then I would only take safe pictures, that way I wouldn’t learn anything. What’s the point? So the way I made this process that I loved financially feasible was to decide that I wasn’t going to take two of anything. I don’t mean not bracket, I mean exactly what you said—not even two views. What it forced me to do was to decide what I wanted.

Advertisement

With the photo of pancakes, I asked the waitress if she minded if I brought out a big camera so I could get a picture. She didn’t, but I wound up having to stand on a chair, and the camera was on a tripod seven feet in the air. Did being so conspicuous affect the photos?

The year before American Surfaces, in ’71, I was using a small 35 mm. I had hair to my shoulders and looked sort of like a hippie, and every now and then I’d be photographing in a neighborhood and some resident would call the police. The cops would ask me, “What are you doing?” and every now and then I was told to get out of the neighborhood. Once I started using a view camera that never happened. That the camera is so conspicuous gives it even greater license. The extreme examples of this are two works from a series that I’ve never shown before—New York City photographs that I did with an 8x10 of people interacting on the street. And I’d never before been more invisible. I would stand at 72nd and Broadway or 52nd and 5th with this big camera, and people would just walk around me. I photographed people at crosswalks, people hailing a cab, and I’d be six feet away from them taking their picture with an 8x10 camera, and no one would be paying any attention to me. But all those landscapes devoid of humans were because you wanted fewer people around to ask you what you were up to?

Part of it was technical. My exposures were typically a half or a quarter of a second, so if I had a person in the shot they had to be either posing for me or stopped at a crosswalk. But I don’t want to say that it was simply technical, because I chose the tools. If having the streets full of people was that important to me and were an essential part of what I was trying to do and I couldn’t have accomplished it with those tools, I would have used different tools. There’s also another factor that those of us who grew up in New York might not recognize. If you go to some intersection in Ashland, Wisconsin, and set up a camera, if you wanted a person in the picture, you’d have to wait. In most of these towns, the streets are not full of people the way they are outside our windows in New York. I now live in a small town. Consequently, those photos have a lot more meaning to me now. But you’ve done such compelling portraits, too. Have you ever consciously shot a series of portraits?

Not really. In American Surfaces, I’d say about a fifth of the pictures are portraits, and that was probably the most extensive. Although my Warhol pictures are pictures of people, they’re not necessarily portraits. There were periods in the 70s when I would come back to portraits. I did a number in Fort Worth in ’76. A few of them have been published. And then I photographed almost every member of the Yankees in ’78. But for a lot of the time in the 70s, I had particular cultural questions on my mind and also particular formal questions that just didn’t relate to portraiture. Critics sometimes refer to your landscapes as “portraits.” But isn’t there some ineffable quality to a human portrait that can’t be applied to objects?

That’s a really good question, and I don’t think there’s a simple answer. Whenever you see a person in a picture, your response is different. It’s not like looking at a mailbox or a lamppost. There’s the attraction of the eye, there’s the focusing on it, and a chain of associations that are all very different. For American Surfaces, I asked everyone before I photographed, “Can I take your picture?” And I was thinking about not just their expressions but what their clothes were and what their backgrounds were, information about their heritage. It fit into a kind of cultural nexus. I think that that work in particular integrated the portrait maybe more successfully than at any other time for me. So what about the description of your landscapes as portraits?

I would say they feel that way because maybe there’s a sense in a portrait of paying very focused attention and respect to someone. That the photographer is showing some respect and is looking carefully at a person. The viewer may pick up that same quality in looking at a building or looking at a street. It’s as if you entered into the same deal with the building as you would a person of whom you’re making a portrait. That quality runs all through your work. I wonder how intentional it is. Or are we getting into quantum science, where intentionality has the power to transform the physical?

That’s exactly the point where my work finally wound up in the 80s when I was doing actual natural landscapes. That is what I was exploring—how responsive this very mechanical medium can be to subtle shifts in the state of mind of the artist. There’s a recurring theme in The Nature of Photographs. You advocate developing a closer relationship with all of our senses—paying more attention to how they work and training ourselves to better monitor what they’re trying to tell us. Your best pictures are examples of just that.

A photograph can do many things at once. I can be exploring culture or I can be making decisions about what street to photograph to give a taste of this town or this age. At the same time, I can explore the medium formally, explore how the structure of a picture may give a taste of an age, how perception works, and how a photograph plays with it. I can also explore what you were saying, that sometimes the most mundane subject matter is the most telling because what gives the picture charge isn’t the cultural charge of the content as much as the awareness of the senses and the awareness of perception giving it a kind of visual resonance. It’s like those days or moments when maybe your mind gets a little quieter and space becomes more tangible, textures and colors become more vivid.

Advertisement

Yes, it’s one of the things I learned from the process of photography. Let me give an example. I think it’s absolutely typical that you could leave your house and have a certain walk to a café every day and not really pay attention to what’s around you, but if you put a camera on your shoulder, all of a sudden you do. What can I learn from that? To address it in a different way, when I was photographing the Yankees I would see these people who were performing mind-boggling feats of attention. I’ve been going to baseball games since I was six, but from the stands there’s no way to experience what a major-league fastball looks like from the batter’s perspective. At spring training in Fort Lauderdale, I was able to stand essentially where the umpire was and watch these pitches being thrown. That anyone can even hit a fastball is an amazing feat of attention and coordination. But if you talk to them, they’ll say that when they’re really in the flow of it, they’re watching the rotation of the stitches on the ball. Yet these same people who are able to perform this so well would at four in the afternoon go to a bar called Trader Jack’s and try to pick up young girls and forget the state of mind that they had achieved that even allowed them to see the ball. They weren’t carrying the lesson of that into the rest of their lives. I wonder why we don’t go through our lives paying closer attention, and what would accrue from doing that. In the 90s you published a book of photographs called Essex County. It featured compelling and, I have to say, strange images of trees, flora, etc. It seemed almost a break from the earlier work, but in some hard-to-pin-down way.

There are a number of things I could say to that. One thing is that I take pictures to solve problems, visual problems, and the picture is the byproduct of that. I find that when I work everything out [in the problem], I don’t want to repeat myself. It’s my nature to keep trying to push myself into new directions. That’s one of the reasons that particular work looks so different from what I’d done before. I’d worked out a number of problems in my streetscapes of the 70s and my landscapes of the 80s, and by the time I got to this body of work my concern was for seeing with a kind of deeper resonance. I want to present you with four of your best-known portraits and have you tell me something about their circumstances. The first is New York City, New York, September–October 1972, a shot of Henry Geldzahler.

It was at a party. I had known Henry since the mid-60s. I think there’s something delightful about him eating the apple. The book it’s in, American Surfaces, began as a cross-country trip, and I photographed different categories of things repeatedly, including everyone I met. I continued this after I got back to my home in the city. I never identified the people, but it’s a mixture of very close friends and someone I would run into in a bus depot in Oklahoma City, or a gas-station attendant. A whole range of people, whether or not identified. There’s Senator Javits, the Earl of Gowrie, and the great avant-garde film critic P. Adams Sitney. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, July, 1972.

This is someone I met, I think, in a bus depot. The Trailways bus depot in Oklahoma City. I just thought he was a wonderful character. Self-Portrait, New York, NY, 3/20/76.

The self-portrait is set up. I was looking at things like the tape coming from the adding machine. I was thinking of these little details and how to arrange it. But I can’t remember what else was on my mind. Lee Cramer, Bel Air, Maryland, 1983.

It was my father-in-law in his kitchen. I’ll say this about portraits in general that I find very interesting: Facial expressions and signs that we’re culturally attuned to pick up on read as particular emotions. There is also the problem that facial expressions flow in time and, taken out of the context of their time by a still photograph, can mean something different than they actually are. Nonetheless, we’re left with this result that we read emotion and experience into. A wonderful example is a book of portraits made by the photographer Robert Lyons of both perpetrators and surviving victims of the Rwandan genocide. They are not titled; they’re indexed in the back of the book. They’re faces of men that have a look in their eye of depth of experience and wisdom and compassion… visual symbols we read as those things. Then in the back you read that this person ordered the death of 17 people. A wonderful photographer named Tod Papageorge, who is a good friend of mine, photographed my wedding. It was in California and he came out and photographed people that he had never met before that day. And in his pictures every single one of these people is shown in their essence. So on the one hand we know there is something deeply fictive about a portrait and yet on the other there’s this result where I see Tod’s penetrating insight in understanding people. I also feel that the picture of my father-in-law does communicate something about his state of mind. And that is the conundrum of the portrait.

Advertisement