WORDS: JAIMIE HODGSON

PHOTOS: ALEX STURROCK

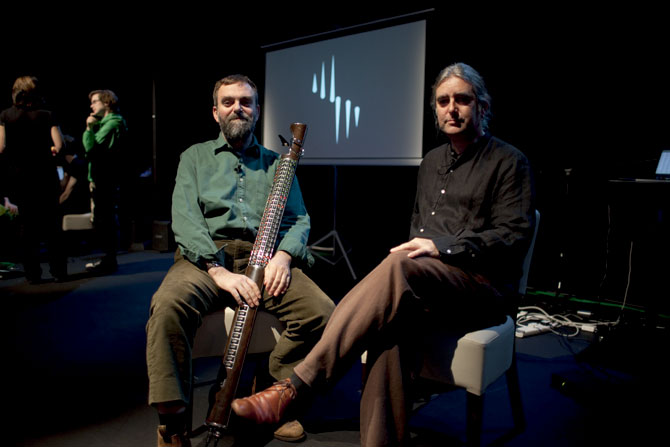

The Eigenharp is the ultimate synth-geek fantasy made real. It resembles what Rick Wakeman might’ve ended up playing if JG Ballard had directed one of his Journey to the Centre of the Earth -era promo videos. But in its capabilities, there is no doubt that it far outstrips any electronic instrument that’s gone before.

In 1993, John Lambert, a physics graduate from Imperial College London, had ended up running a small pocket of cheap-to-rent rehearsal and recording studios in south London.

He formed a band called Shen with a pal called Richard Ashroman. They specialised in playing six-hour concerts of music that dipped its wick in every single musical genre in the world. They’d perform these long concerts while drugged-up clubbers melted into the floor.

I recently met John at a demo of the Eigenharp and he told me: “We only ever had two hours of written material and the sets often lasted for six or seven hours, so a great deal of improvising was called upon. We’d have guest choirs, Indian dancers, saxophonists who’d run through the audience. It was basically a fusion of everything a bit out-there. Pretty far-out stuff.”

John’s problem was that his workstation of keyboards, consoles, gadgets, pre-amps, wires, wires, and lots more wires, was vast.

“It would take me at least three hours to set everything up before every single gig,” he remembers. “I would go to play acoustic folky stuff down the local pub with my guitar and it would take 30 seconds to set up. The gulf between the two situations was just nonsensical to me.”

It was this frustration that led John to desire one electronic instrument that could house every single sound, sample, beat and filter that was contained within his armoury of musical equipment.

He dreamed of a synthesiser that, through its responsive intricacies, could accommodate true virtuoso-ism, like any classical instrument. In short, John wanted to make the ultimate synth.

Sadly, but probably unsurprisingly, the government turned down his application for a £100,000 grant. Dejected, John decided to put his dream on hold and plough his large brain into other territories. Rather fortuitously, he chose to devote his energies to another emerging wacky tech innovation called the internet. Against plenty of advice from friends and family, he set up one of the world’s first web agencies, which he called Hyperlink. As luck would have it, over the next six years Hyperlink would go on to become the most successful web agency in the UK. It was sold to Cable and Wireless in 1999 for approximately £28 squillion. “We had some exciting years,” John says, “but all along I had this nagging throb in the back of my head. The dream of the Eigenharp was subconsciously guiding me, I think. I knew that all this time and money was building towards something.

“I converted my barn in Exeter into a kind of top-secret think-tank-cum-workshop and we set out designing the Eigenharp. There were five of us at first, expanding when we needed, eventually building to a staff of 40.

“I said we’d be shipping within 18 months. And, well, ten years later we’re ready for our first order.”

So what’s so amazing about the Eigenharp? Well, from what I saw at a demonstration held in London recently, it can effectively do anything that any sampler and sequencer ever created can do TIMES INFINITY. It has 120 main keys that can be manipulated 360 degrees. At either end of every key an entirely different effect or filter can be assigned. Between those, 12 percussion pads, two strip controllers and, most peculiarly, a “synth wind-pipe”, they’d constructed a formidable electronic instrument that has literally no limits. It’s like when you try to comprehend the scale of space, considering that our universe is just a speck within a galaxy, within another galaxy.

On the Eigenharp, for example, any sample or sound could be assigned to any controller with the kind of memory that could store 1000-piece orchestral arrangements chronicling the entire works of Mozart. For power, these engineers had to invent their own processing system that is 100 times faster than the industry standard, MIDI. They managed to distil every piece of machinery they’d experienced over the past 20 years inside a classy-looking wood-finish case (it will also be available in maple, ivory, oak and other finishes).

In a world where record sales are waning and fees and royalties for live performances are vitally important, this offers a lifeline for the jobbing keyboardist imprisoned behind their rack of hardware. With this baby harnessed to them, the stage is the performer’s playground. They can truly express themselves on the Eigenharp. Well, that is, if they’re prepared to look like a bit of a ninny playing an instrument that could have been pinched from the cantina band in Star Wars.

“The ultimate scenario for me,” John says, “would be the Eigenharp being played as part of a classical orchestra, as well as in a gothic metal band, as well as part of a live electronica group, as well as within, who knows, maybe a hip-hop project too. Such is the total versatility of the instrument, it’s destined to be embraced universally.

“For us,” he adds, “the aim of the Eigenharp was to create something that would be universally embraced. And to pave the way for the future of all live music.”

Watch the Eigenharp documentary on the Motherboard series on VBS.TV.

PHOTOS: ALEX STURROCK

The Eigenharp is the ultimate synth-geek fantasy made real. It resembles what Rick Wakeman might’ve ended up playing if JG Ballard had directed one of his Journey to the Centre of the Earth -era promo videos. But in its capabilities, there is no doubt that it far outstrips any electronic instrument that’s gone before.

In 1993, John Lambert, a physics graduate from Imperial College London, had ended up running a small pocket of cheap-to-rent rehearsal and recording studios in south London.

He formed a band called Shen with a pal called Richard Ashroman. They specialised in playing six-hour concerts of music that dipped its wick in every single musical genre in the world. They’d perform these long concerts while drugged-up clubbers melted into the floor.

I recently met John at a demo of the Eigenharp and he told me: “We only ever had two hours of written material and the sets often lasted for six or seven hours, so a great deal of improvising was called upon. We’d have guest choirs, Indian dancers, saxophonists who’d run through the audience. It was basically a fusion of everything a bit out-there. Pretty far-out stuff.”

John’s problem was that his workstation of keyboards, consoles, gadgets, pre-amps, wires, wires, and lots more wires, was vast.

“It would take me at least three hours to set everything up before every single gig,” he remembers. “I would go to play acoustic folky stuff down the local pub with my guitar and it would take 30 seconds to set up. The gulf between the two situations was just nonsensical to me.”

It was this frustration that led John to desire one electronic instrument that could house every single sound, sample, beat and filter that was contained within his armoury of musical equipment.

He dreamed of a synthesiser that, through its responsive intricacies, could accommodate true virtuoso-ism, like any classical instrument. In short, John wanted to make the ultimate synth.

Sadly, but probably unsurprisingly, the government turned down his application for a £100,000 grant. Dejected, John decided to put his dream on hold and plough his large brain into other territories. Rather fortuitously, he chose to devote his energies to another emerging wacky tech innovation called the internet. Against plenty of advice from friends and family, he set up one of the world’s first web agencies, which he called Hyperlink. As luck would have it, over the next six years Hyperlink would go on to become the most successful web agency in the UK. It was sold to Cable and Wireless in 1999 for approximately £28 squillion. “We had some exciting years,” John says, “but all along I had this nagging throb in the back of my head. The dream of the Eigenharp was subconsciously guiding me, I think. I knew that all this time and money was building towards something.

“I converted my barn in Exeter into a kind of top-secret think-tank-cum-workshop and we set out designing the Eigenharp. There were five of us at first, expanding when we needed, eventually building to a staff of 40.

“I said we’d be shipping within 18 months. And, well, ten years later we’re ready for our first order.”

So what’s so amazing about the Eigenharp? Well, from what I saw at a demonstration held in London recently, it can effectively do anything that any sampler and sequencer ever created can do TIMES INFINITY. It has 120 main keys that can be manipulated 360 degrees. At either end of every key an entirely different effect or filter can be assigned. Between those, 12 percussion pads, two strip controllers and, most peculiarly, a “synth wind-pipe”, they’d constructed a formidable electronic instrument that has literally no limits. It’s like when you try to comprehend the scale of space, considering that our universe is just a speck within a galaxy, within another galaxy.

On the Eigenharp, for example, any sample or sound could be assigned to any controller with the kind of memory that could store 1000-piece orchestral arrangements chronicling the entire works of Mozart. For power, these engineers had to invent their own processing system that is 100 times faster than the industry standard, MIDI. They managed to distil every piece of machinery they’d experienced over the past 20 years inside a classy-looking wood-finish case (it will also be available in maple, ivory, oak and other finishes).

In a world where record sales are waning and fees and royalties for live performances are vitally important, this offers a lifeline for the jobbing keyboardist imprisoned behind their rack of hardware. With this baby harnessed to them, the stage is the performer’s playground. They can truly express themselves on the Eigenharp. Well, that is, if they’re prepared to look like a bit of a ninny playing an instrument that could have been pinched from the cantina band in Star Wars.

“The ultimate scenario for me,” John says, “would be the Eigenharp being played as part of a classical orchestra, as well as in a gothic metal band, as well as part of a live electronica group, as well as within, who knows, maybe a hip-hop project too. Such is the total versatility of the instrument, it’s destined to be embraced universally.

“For us,” he adds, “the aim of the Eigenharp was to create something that would be universally embraced. And to pave the way for the future of all live music.”

Watch the Eigenharp documentary on the Motherboard series on VBS.TV.