By Anne De Craemer, Photos By Pieter-Jan De Pue Our hero, Hojatoleslam Hosseini.The room is full of garish plastic flowers that make it impossible to concentrate on what the man seated in front of me is saying. Not helping matters is the overwhelming heat, which has me fidgeting uncomfortably in my chair. The black chador draped over my head—in keeping with Islamic dress code—falls, and a sweaty clump of hair slips to my shoulder. Mr. Hosseini, one of the highest-ranking Islamic leaders in Qom, Iran’s religious capital, doesn’t notice. He is rhapsodizing.“There is a reason why I want to meet personally journalists who visit the Hazrat-e Masumeh shrine,” Hosseini informs me through my translator and guide. “There are many misunderstandings about Islam. I want you to remember this: Islam is peace. Unfortunately, politics always separates people. But we are not hostile to anyone.” Clearly, he means it, but I’m being forced to listen so it isn’t very convincing.I’ve only just arrived in the sleepy city of Qom with my photographer, Pieter-Jan, after a one-week stay in press-packed Tehran. In the taxi from the train station to the city center, our driver was puzzled: “Be khoda, in the name of God, what are you doing here?” Before I could explain that we’re here gathering research for an upcoming book on youth movements, he caught my eye in the rearview mirror, smiled, and shook his head. “There are rarely any foreigners in this city—not even journalists. You will be the talk of the town.” He dropped us at the Hazrat-e Masumeh, the holiest shrine in Qom, and we quickly understood what he meant. “Salam khareji! Hello, foreigner!” a young man waved at me from the other side of the street. “Be behesht khosh amadid! Welcome to paradise!”

Our hero, Hojatoleslam Hosseini.The room is full of garish plastic flowers that make it impossible to concentrate on what the man seated in front of me is saying. Not helping matters is the overwhelming heat, which has me fidgeting uncomfortably in my chair. The black chador draped over my head—in keeping with Islamic dress code—falls, and a sweaty clump of hair slips to my shoulder. Mr. Hosseini, one of the highest-ranking Islamic leaders in Qom, Iran’s religious capital, doesn’t notice. He is rhapsodizing.“There is a reason why I want to meet personally journalists who visit the Hazrat-e Masumeh shrine,” Hosseini informs me through my translator and guide. “There are many misunderstandings about Islam. I want you to remember this: Islam is peace. Unfortunately, politics always separates people. But we are not hostile to anyone.” Clearly, he means it, but I’m being forced to listen so it isn’t very convincing.I’ve only just arrived in the sleepy city of Qom with my photographer, Pieter-Jan, after a one-week stay in press-packed Tehran. In the taxi from the train station to the city center, our driver was puzzled: “Be khoda, in the name of God, what are you doing here?” Before I could explain that we’re here gathering research for an upcoming book on youth movements, he caught my eye in the rearview mirror, smiled, and shook his head. “There are rarely any foreigners in this city—not even journalists. You will be the talk of the town.” He dropped us at the Hazrat-e Masumeh, the holiest shrine in Qom, and we quickly understood what he meant. “Salam khareji! Hello, foreigner!” a young man waved at me from the other side of the street. “Be behesht khosh amadid! Welcome to paradise!” Hazrat-e Masumeh: The holiest shrine in Qom, one of Iran’s most holy cities.We had barely entered the shrine when the head supervisor insisted we come with him to the office of the localhojatoleslam. This title is given to clerics of advanced standing in Islamic studies—in essence, influential interpreters of the Koran and setters of the moral standard. They wield immense power in every echelon of Iranian culture, and it was made obvious that if we refused to meet with him, we would not be interviewing or photographing anyone anytime soon. “Don’t worry. Mr. Hosseini just wants a friendly talk with you,” the supervisor said to us. I’d had a similar chat with civil authorities in Tehran—it is a strange thing to get accustomed to.But here we are, in a steamy room with Hojatoleslam Hosseini. The discussion turns to tyranny, injustice, and other very bad things that Islam stands against. “It grieves me that there are so many people who commit crimes in the name of Islam,” Hosseini begins. “Keep this in mind: The Taliban and suicide bombers have nothing to do with Islam. Nothing at all. They are uneducated people.” His eyebrow raises slightly. “If theydidreceive any education, it was in the United States. As you know, Osama bin Laden and other important Taliban leaders were trained and educated in America.”I nod politely and take a sip of the tea set out for me by Hosseini’s secretary, who is sitting in a corner of the room dutifully acting interested. Sweat trickles down his face and he is holding a crumpled handkerchief in one hand and a cell phone in the other. There are holes in his black socks and I can see two toes poking out.Qom is the heart of Islamic studies in Iran. It is also the city in which the late Ayatollah Khomeini first attacked the quasi-American-friendly shah’s policies in 1962. This prompted the shah to imprison and ultimately expel Khomeini from Iran in 1964—in effect igniting the conservative Islamic Revolution Khomeini led, which, to some extent, continues to this day. The same one Hosseini is trying so hard to untangle for me.But his voice is growing weaker by the minute. He is caught in a coughing fit and his face turns bright red. He smiles back at me when he notices my concern. “Inshallah, we will have a more peaceful world tomorrow,” he tells me. “You have your Jesus and we have our Mahdi. Both of them will come back and create a revolution in the world, which will then be a perfect place.” Not long after this we are free to go.I’m relieved to be back in the streets. The forthcoming presidential election has invigorated Qom. Women hold their black chadors with one hand and clutch a picture of incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in the other. A boy has a green parakeet on his arm. Iranians believe parakeets can predict the future, so I ask him what the next four years have in store for his country: “Ahmadinejad!” He smiles radiantly and his father nods approvingly.

Hazrat-e Masumeh: The holiest shrine in Qom, one of Iran’s most holy cities.We had barely entered the shrine when the head supervisor insisted we come with him to the office of the localhojatoleslam. This title is given to clerics of advanced standing in Islamic studies—in essence, influential interpreters of the Koran and setters of the moral standard. They wield immense power in every echelon of Iranian culture, and it was made obvious that if we refused to meet with him, we would not be interviewing or photographing anyone anytime soon. “Don’t worry. Mr. Hosseini just wants a friendly talk with you,” the supervisor said to us. I’d had a similar chat with civil authorities in Tehran—it is a strange thing to get accustomed to.But here we are, in a steamy room with Hojatoleslam Hosseini. The discussion turns to tyranny, injustice, and other very bad things that Islam stands against. “It grieves me that there are so many people who commit crimes in the name of Islam,” Hosseini begins. “Keep this in mind: The Taliban and suicide bombers have nothing to do with Islam. Nothing at all. They are uneducated people.” His eyebrow raises slightly. “If theydidreceive any education, it was in the United States. As you know, Osama bin Laden and other important Taliban leaders were trained and educated in America.”I nod politely and take a sip of the tea set out for me by Hosseini’s secretary, who is sitting in a corner of the room dutifully acting interested. Sweat trickles down his face and he is holding a crumpled handkerchief in one hand and a cell phone in the other. There are holes in his black socks and I can see two toes poking out.Qom is the heart of Islamic studies in Iran. It is also the city in which the late Ayatollah Khomeini first attacked the quasi-American-friendly shah’s policies in 1962. This prompted the shah to imprison and ultimately expel Khomeini from Iran in 1964—in effect igniting the conservative Islamic Revolution Khomeini led, which, to some extent, continues to this day. The same one Hosseini is trying so hard to untangle for me.But his voice is growing weaker by the minute. He is caught in a coughing fit and his face turns bright red. He smiles back at me when he notices my concern. “Inshallah, we will have a more peaceful world tomorrow,” he tells me. “You have your Jesus and we have our Mahdi. Both of them will come back and create a revolution in the world, which will then be a perfect place.” Not long after this we are free to go.I’m relieved to be back in the streets. The forthcoming presidential election has invigorated Qom. Women hold their black chadors with one hand and clutch a picture of incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in the other. A boy has a green parakeet on his arm. Iranians believe parakeets can predict the future, so I ask him what the next four years have in store for his country: “Ahmadinejad!” He smiles radiantly and his father nods approvingly. The English class Ann and Pieter-Jan were asked to join after their arrest. In case you can’t make out the words written on the board, they are weapon, justice, and sink.Down the street, a crowd is jostling near a wall that is covered in green, the color of the opposition party. Even in this decidedly conservative city, supporters of the president’s primary rival, Mir-Hossein Mousavi, have set up camp. Dozens of people crowd around me, begging to be interviewed. An old man is pointing at a Mousavi poster and making the peace sign. A mullah is watching us all, the Koran in his left hand and an iPhone in his right.A few hours later, we are stopped by three policemen. One of them shows me a press card with a picture of Pieter-Jan. “Do you know this guy?” he asks. Through my translator I answer yes, knowing that Pieter-Jan is down the street taking pictures of Mousavi supporters. He orders us to follow him but stops to look at me contemptuously: “You have badhejabi—you are not observing the Islamic dress code.” I have my translator ask him what the problem is, as I am wearing a very wide shirt that reaches almost down to my knees. The officer snaps at me: My dress is still way too short. “Maybe this will do in the streets of Tehran, but this is the city of Qom.”Pieter-Jan and I are placed under arrest. They lead us to the detention center, which is a far cry from a police station. It’s more like a ministry. The three arresting officers are conversing on walkie-talkies, and the man behind the desk is staring at us in silence. An impeccably dressed young man appears in the doorway and greets us with an American accent. “Hi there! Would you like to take part in my English class?” The officers are grinning. I tell him that we would rather stay where we are, but again we have no choice. A door is opened and 20 curious eyes focus on us. “These are my students! Please sit down. What do you think about Iran? And what about Qom?” The situation is so absurd that it’s difficult not to laugh. Isthisour punishment for having talked to the opposition and for my “badhejabi”?There is no time to be puzzled: The cop enters the classroom and orders us to follow him outside. For the first time our guide seems confused—almost worried. “They are assholes,” a teenage boy whispers to me in English when we are back on the street. “We hate them. We have problems with them every day. Don’t show them you are scared. They just love that.”We are being escorted to the police station, and officers begin to congregate around us. It no longer feels like a formality.

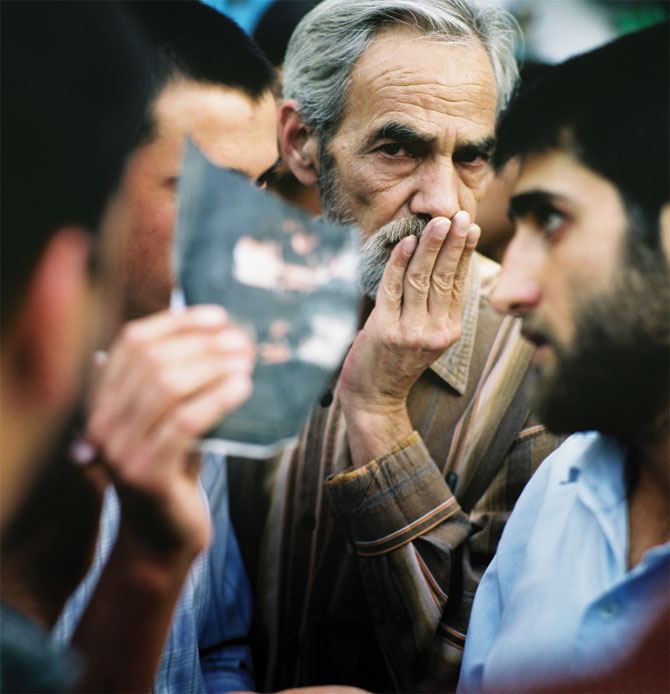

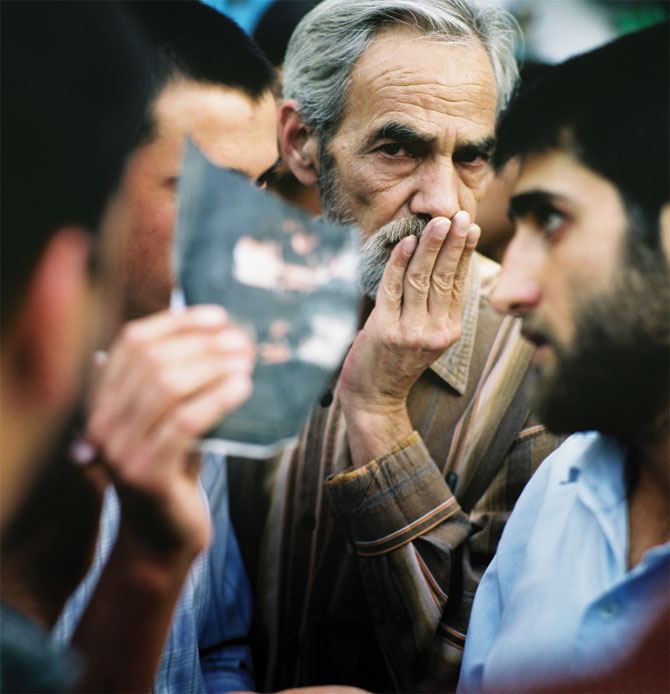

The English class Ann and Pieter-Jan were asked to join after their arrest. In case you can’t make out the words written on the board, they are weapon, justice, and sink.Down the street, a crowd is jostling near a wall that is covered in green, the color of the opposition party. Even in this decidedly conservative city, supporters of the president’s primary rival, Mir-Hossein Mousavi, have set up camp. Dozens of people crowd around me, begging to be interviewed. An old man is pointing at a Mousavi poster and making the peace sign. A mullah is watching us all, the Koran in his left hand and an iPhone in his right.A few hours later, we are stopped by three policemen. One of them shows me a press card with a picture of Pieter-Jan. “Do you know this guy?” he asks. Through my translator I answer yes, knowing that Pieter-Jan is down the street taking pictures of Mousavi supporters. He orders us to follow him but stops to look at me contemptuously: “You have badhejabi—you are not observing the Islamic dress code.” I have my translator ask him what the problem is, as I am wearing a very wide shirt that reaches almost down to my knees. The officer snaps at me: My dress is still way too short. “Maybe this will do in the streets of Tehran, but this is the city of Qom.”Pieter-Jan and I are placed under arrest. They lead us to the detention center, which is a far cry from a police station. It’s more like a ministry. The three arresting officers are conversing on walkie-talkies, and the man behind the desk is staring at us in silence. An impeccably dressed young man appears in the doorway and greets us with an American accent. “Hi there! Would you like to take part in my English class?” The officers are grinning. I tell him that we would rather stay where we are, but again we have no choice. A door is opened and 20 curious eyes focus on us. “These are my students! Please sit down. What do you think about Iran? And what about Qom?” The situation is so absurd that it’s difficult not to laugh. Isthisour punishment for having talked to the opposition and for my “badhejabi”?There is no time to be puzzled: The cop enters the classroom and orders us to follow him outside. For the first time our guide seems confused—almost worried. “They are assholes,” a teenage boy whispers to me in English when we are back on the street. “We hate them. We have problems with them every day. Don’t show them you are scared. They just love that.”We are being escorted to the police station, and officers begin to congregate around us. It no longer feels like a formality. Mousavi supporters arguing with disciples of Ahmadinejad shortly before the election.We arrive, and pairs of officers remove their combat boots and chuckle with one another. I am seated and then ignored. Our guide begins a loud discussion with one of the policemen in Farsi: “But wedohave permission to work here! The document you are asking for is still at the hojatoleslam’s office.” By “we” he of course means me and the other white person, Pieter-Jan. The officer accuses him of lying and marches off, mumbling something to his colleague, who laughs hysterically. On the small television set Barack Obama is giving a speech about the Middle East. At the first mention of Iran an officer turns it off.It is ten o’clock at night and the heat is still torturous. Pieter-Jan is offered a glass of cold water. I am ignored. I notice that our guide has disappeared.An hour and a half later I hear voices in the corridor. I look to my left and our guide is standing in the doorway, accompanied by Hojatoleslam Hosseini. The cleric’s face is red and he begins shouting at the policemen.“Aren’t you ashamed of yourselves?” The cops jump to their feet and I find I’m sitting upright myself. “What have these people done wrong? Their official permission to work in Qom wasindeedstill at my office. It was my fault: I forgot to hand it back to them.” He’s livid, and I’m feeling much better about myself. “Shame on you! How ignorant you are! I tell these young people that Islam is peace and this is the way you treat them?”It’s important to note that Hosseini was hosting a dinner party when my guide found him. He had left his guests at the dinner table to apologize to us in person. It seems important to the cleric that we witness him berate these officers, though he is truly embarrassed.There are apologies and awkward exchanges. Outside the station, Hosseini asks me if the policemen have treated me badly. I tell him about the glass of water and he apologizes—this time in perfect English. “Men like those do not respect women. It’s a shame.” He sighs deeply. “They offend my religion. They are ignorant. They are bad. It’s people like them who give Islam and Iran a bad name. I will report this incident to the authorities.” As we say our goodbyes, he generously offers to put me up on my next visit.We leave Qom earlier than planned—the following morning, actually. On the train to Arak we are able to joke about our one-day adventure, but a feeling of unease quickly returns when the results of the presidential elections are announced a few days later. Ahmadinejad has won. We are in Isfahan when this happens. The atmosphere quickly turns gloomy. Whispers about demonstrations begin immediately, but there have been no protests as of yet. The silence in the streets is more frightening than our arrest just days before.With extended visas we are able to continue through the country for another week. We visit the cities of Yazd, Bandar Abbas, and Shiraz, but it’s as though we are in a country that belongs to the prickish “bad hejabi” cop and not Hosseini. Before the elections, Iranians spontaneously approached visitors to chat candidly about their country. Now there is fear and worry in everyone’s eyes, and the opposition rioters are taking to the streets. The government run by clerics of the Khomeini legacy are annoyed and wrench up street patrols, giving cops the authority to subdue protesters with violence. A few days later, along with all other Western journalists, we are forced from the country.

Mousavi supporters arguing with disciples of Ahmadinejad shortly before the election.We arrive, and pairs of officers remove their combat boots and chuckle with one another. I am seated and then ignored. Our guide begins a loud discussion with one of the policemen in Farsi: “But wedohave permission to work here! The document you are asking for is still at the hojatoleslam’s office.” By “we” he of course means me and the other white person, Pieter-Jan. The officer accuses him of lying and marches off, mumbling something to his colleague, who laughs hysterically. On the small television set Barack Obama is giving a speech about the Middle East. At the first mention of Iran an officer turns it off.It is ten o’clock at night and the heat is still torturous. Pieter-Jan is offered a glass of cold water. I am ignored. I notice that our guide has disappeared.An hour and a half later I hear voices in the corridor. I look to my left and our guide is standing in the doorway, accompanied by Hojatoleslam Hosseini. The cleric’s face is red and he begins shouting at the policemen.“Aren’t you ashamed of yourselves?” The cops jump to their feet and I find I’m sitting upright myself. “What have these people done wrong? Their official permission to work in Qom wasindeedstill at my office. It was my fault: I forgot to hand it back to them.” He’s livid, and I’m feeling much better about myself. “Shame on you! How ignorant you are! I tell these young people that Islam is peace and this is the way you treat them?”It’s important to note that Hosseini was hosting a dinner party when my guide found him. He had left his guests at the dinner table to apologize to us in person. It seems important to the cleric that we witness him berate these officers, though he is truly embarrassed.There are apologies and awkward exchanges. Outside the station, Hosseini asks me if the policemen have treated me badly. I tell him about the glass of water and he apologizes—this time in perfect English. “Men like those do not respect women. It’s a shame.” He sighs deeply. “They offend my religion. They are ignorant. They are bad. It’s people like them who give Islam and Iran a bad name. I will report this incident to the authorities.” As we say our goodbyes, he generously offers to put me up on my next visit.We leave Qom earlier than planned—the following morning, actually. On the train to Arak we are able to joke about our one-day adventure, but a feeling of unease quickly returns when the results of the presidential elections are announced a few days later. Ahmadinejad has won. We are in Isfahan when this happens. The atmosphere quickly turns gloomy. Whispers about demonstrations begin immediately, but there have been no protests as of yet. The silence in the streets is more frightening than our arrest just days before.With extended visas we are able to continue through the country for another week. We visit the cities of Yazd, Bandar Abbas, and Shiraz, but it’s as though we are in a country that belongs to the prickish “bad hejabi” cop and not Hosseini. Before the elections, Iranians spontaneously approached visitors to chat candidly about their country. Now there is fear and worry in everyone’s eyes, and the opposition rioters are taking to the streets. The government run by clerics of the Khomeini legacy are annoyed and wrench up street patrols, giving cops the authority to subdue protesters with violence. A few days later, along with all other Western journalists, we are forced from the country.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement