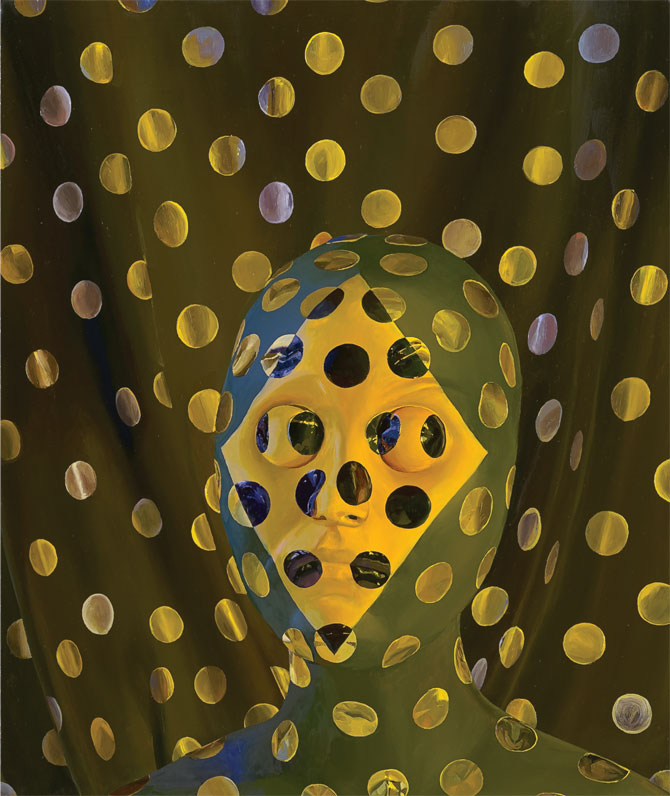

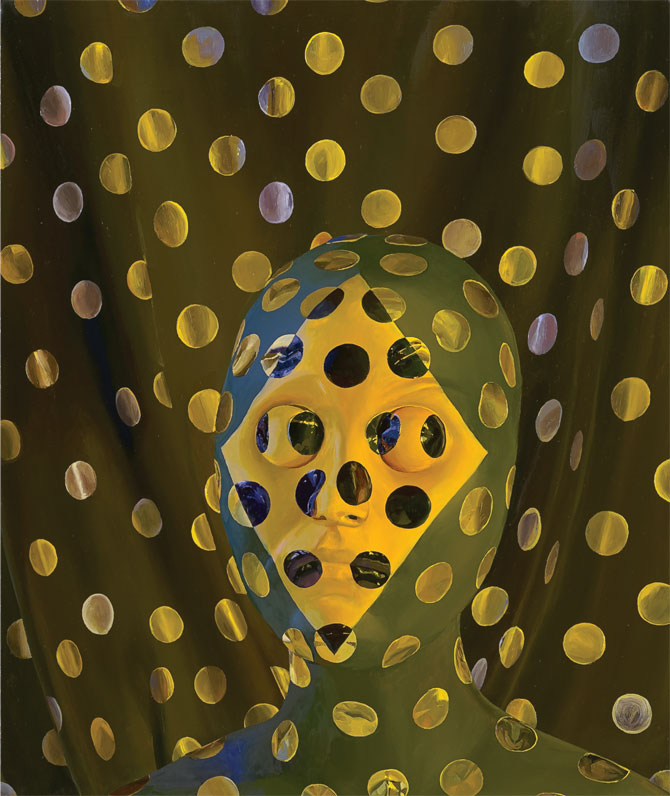

PAINTINGS BY SASCHA BRAUNIG Sascha Braunig, Chameleon, 2011, oil on canvas, 24 x 20 inches. Courtesy of Foxy Production, New York.

Sascha Braunig, Chameleon, 2011, oil on canvas, 24 x 20 inches. Courtesy of Foxy Production, New York.

Lynne Tillman is an author, essayist, art critic, and the fiction editor of Fence magazine. Many well-read individuals recognize Lynne’s 2006 novel American Genius, a Comedy as part of a cautiously guarded canon that includes Gravity’s Rainbow, Infinite Jest, The Dead Father, White Noise, etc. It will teach you lots of things about Zulu, the Manson family, chair design, and what life’s like for an extremely intelligent middle-aged woman stuck in an asylum. Hence we are extremely proud to present an exclusive extract from Lynne’s novel-in-progress, which will tentatively share the title of this sneak preview. We’ve coupled the story with paintings by Sascha Braunig whose portrayals of hypnotic, iridescent beings were met with acclaim at her first solo exhibition at Foxy Production in New York last spring. Her work, like Lynne’s, makes our brains feel weird in very good ways.

The end doesn’t depend on the beginning. The end may be the beginning of other possible endings.

There’s a story in my family about Great-Uncle Ezekiel, who didn’t know, until he was 18 and married to Margaret, that women went to the bathroom. It’s always told with this euphemism. My father, whose uncle Ezekiel was, told it to my older brother, Hart, when he was 13, then me at 13—a father-son rite of passage—and his two brothers told their sons, and then their daughters, when the fathers loosened up about girls.

My kid sister, Clover, baby of the family, was named after a minor-league 19th-century figure on my mother’s side, a great-great-great-ancestor. Historical Clover had a tragic end, but Mother liked the woman, the name, and gave it to her baby girl. Also Mother felt attached to her family in a mystical way, she said. I thought it was creepy, given the provenance, but you can’t argue with mysticism; you just need to know your enemy. For a long time, I stayed out of all that, or tried to be objective. That was when I had hope for objectivity. But the mind is weaker than the flesh. Just kidding. My father didn’t know that much about his genealogy. They came from different parts of the old country, his mother, German-Scottish-Irish, father, Russian Jewish and Austrian, all from the mid- to late 1800s. The usual immigrant deal: Fourth and fifth generations not only don’t refer to the old country but also never think about it; brothers became professionals, sisters married well. My father’s an agnostic and a lawyer, or maybe the same deal, Damned with Doubt.

My mother thinks she is America. Her family arrived on the Mayflower—with the criminals, Mother; the religious crackpots, Mother. Man, she gets pissed. We were poets, feminists, abolitionists, politicians, she says. Her Boston people hung with the Henry James crowd; but when she came of age, she let family privilege go, which was part of her privilege. Image was a personal issue for my mother; the way I’d put it, it was in the family as ancestor worship, and she knew herself as an image from birth, distanced or not. Her family’s house was decorated with ancestral portraits by respectable English and American painters, and later on 19th-century photographers. Mother was our only family photographer, until I was eight and she gave me a cool camera. She owned a Zeiss Ikon, and my father bought the first Polaroid camera in 1962. In 1982 Kodak launched disc photography, the easy-to-use, “decision-free” cameras built around a rotating disc of film. Mom bought me that. It was cool, unfussy. Primitive now. I loved it, but I was more interested in bugs and rockets then. Then, at about 12, I went crazy for photography. You could say it became everything to me.

I was a boy who didn’t kill insects or torture small creatures, except my sister; she believes adamantly that I tortured her. Tormented, that’s more like it. When I was six, I found ecstasy in our backyard. A praying mantis appeared. I didn’t know what it was, but it rocked my world. I watched its little head turning on its neck—the only insect on earth that turns its head, like a person. They’re dinosaur humans. PMs have a face and look you in the eyes. Theirs are in the middle of their tiny heads, and they see the way we do. So cool. The PM noticed me, looked right at me. I thought I was face-to-face with a god or an alien, E.T. is a PM. The PM really took me in, with sympathy and intelligence. I wanted him for a pet, a friend, and named him Mr. Petey. (My parents wouldn’t let me bring him indoors.) I could talk to him—it could have been female—he listened better than my parents, and pretty much every day I went into the backyard to find him. Mr. Petey usually showed up. I never touched him. You can’t kill a PM, my mother said, huffily, they’re a protected species, and if you kill one, we’ll have to pay the government a lot of money. I wasn’t ever going to kill Petey, she was crazy, but learning about the existence of a protected species thrilled my kid-brain. Still does. I wondered if I was one, a special boy with special powers because I knew Mr. Petey. I reveled in talking with Mr. Petey. You can’t find a PM stuffed animal, so I made drawings, and my mother sewed me one. I still have it, Petey’s head flops down after all these years. Mr. Petey has seen it all—Mr. Petey, plural. I didn’t know then that he/she lives only one year. A PM’s short life span fundamentally defies the value of human longevity, its evolutionary merit. The flaws therein.

I must’ve fooled myself—actually, kids don’t fool themselves—when a new PM showed up, because their markings and colors vary. I don’t know what I thought. But a PM arrived in the spring and stayed through summer, I called him/her Mr. Petey, and then one day Mr. Petey went for a vacation, in the South. I figured that out for myself. And that was always Mr. Petey in the backyard, until I left home.

I was a dreamy kid. I’m not so dreamy now. Maybe I am still, but in a different way, and my dreaminess is more blocked to me. Or it was, until recently. Anyway, I had dreamed about being a medical doctor because of Dad’s brother Lionel. He told me people wore green uniforms in the hospital. I figured he jumped around in the halls like a big insect, the way he did in our house. But older bro Hart went into medicine, so that got taken. When Uncle Lionel was drunk, he lunged at the couch, collapsed, and slept like the dead until he was pulled off by his wife (Aunt Marnie). My father drank too, but held it better, and he was an estate lawyer.

Lionel took the big hit, a onetime muscle-destroying heart attack. My miserable father battled esophageal cancer. People mostly lose this one, and eventually he did too, not so long ago. Through his breathing tube, Dad spat out his last words to me. Nothing spiritual from an estate lawyer: Get your money out of the market. I almost forgave him for that, later.

I’m so running ahead of myself.

1) Not a good time in my life. In most ways, not.

Lynne Tillman is an author, essayist, art critic, and the fiction editor of Fence magazine. Many well-read individuals recognize Lynne’s 2006 novel American Genius, a Comedy as part of a cautiously guarded canon that includes Gravity’s Rainbow, Infinite Jest, The Dead Father, White Noise, etc. It will teach you lots of things about Zulu, the Manson family, chair design, and what life’s like for an extremely intelligent middle-aged woman stuck in an asylum. Hence we are extremely proud to present an exclusive extract from Lynne’s novel-in-progress, which will tentatively share the title of this sneak preview. We’ve coupled the story with paintings by Sascha Braunig whose portrayals of hypnotic, iridescent beings were met with acclaim at her first solo exhibition at Foxy Production in New York last spring. Her work, like Lynne’s, makes our brains feel weird in very good ways.

The end doesn’t depend on the beginning. The end may be the beginning of other possible endings.

There’s a story in my family about Great-Uncle Ezekiel, who didn’t know, until he was 18 and married to Margaret, that women went to the bathroom. It’s always told with this euphemism. My father, whose uncle Ezekiel was, told it to my older brother, Hart, when he was 13, then me at 13—a father-son rite of passage—and his two brothers told their sons, and then their daughters, when the fathers loosened up about girls.

My kid sister, Clover, baby of the family, was named after a minor-league 19th-century figure on my mother’s side, a great-great-great-ancestor. Historical Clover had a tragic end, but Mother liked the woman, the name, and gave it to her baby girl. Also Mother felt attached to her family in a mystical way, she said. I thought it was creepy, given the provenance, but you can’t argue with mysticism; you just need to know your enemy. For a long time, I stayed out of all that, or tried to be objective. That was when I had hope for objectivity. But the mind is weaker than the flesh. Just kidding. My father didn’t know that much about his genealogy. They came from different parts of the old country, his mother, German-Scottish-Irish, father, Russian Jewish and Austrian, all from the mid- to late 1800s. The usual immigrant deal: Fourth and fifth generations not only don’t refer to the old country but also never think about it; brothers became professionals, sisters married well. My father’s an agnostic and a lawyer, or maybe the same deal, Damned with Doubt.

My mother thinks she is America. Her family arrived on the Mayflower—with the criminals, Mother; the religious crackpots, Mother. Man, she gets pissed. We were poets, feminists, abolitionists, politicians, she says. Her Boston people hung with the Henry James crowd; but when she came of age, she let family privilege go, which was part of her privilege. Image was a personal issue for my mother; the way I’d put it, it was in the family as ancestor worship, and she knew herself as an image from birth, distanced or not. Her family’s house was decorated with ancestral portraits by respectable English and American painters, and later on 19th-century photographers. Mother was our only family photographer, until I was eight and she gave me a cool camera. She owned a Zeiss Ikon, and my father bought the first Polaroid camera in 1962. In 1982 Kodak launched disc photography, the easy-to-use, “decision-free” cameras built around a rotating disc of film. Mom bought me that. It was cool, unfussy. Primitive now. I loved it, but I was more interested in bugs and rockets then. Then, at about 12, I went crazy for photography. You could say it became everything to me.

I was a boy who didn’t kill insects or torture small creatures, except my sister; she believes adamantly that I tortured her. Tormented, that’s more like it. When I was six, I found ecstasy in our backyard. A praying mantis appeared. I didn’t know what it was, but it rocked my world. I watched its little head turning on its neck—the only insect on earth that turns its head, like a person. They’re dinosaur humans. PMs have a face and look you in the eyes. Theirs are in the middle of their tiny heads, and they see the way we do. So cool. The PM noticed me, looked right at me. I thought I was face-to-face with a god or an alien, E.T. is a PM. The PM really took me in, with sympathy and intelligence. I wanted him for a pet, a friend, and named him Mr. Petey. (My parents wouldn’t let me bring him indoors.) I could talk to him—it could have been female—he listened better than my parents, and pretty much every day I went into the backyard to find him. Mr. Petey usually showed up. I never touched him. You can’t kill a PM, my mother said, huffily, they’re a protected species, and if you kill one, we’ll have to pay the government a lot of money. I wasn’t ever going to kill Petey, she was crazy, but learning about the existence of a protected species thrilled my kid-brain. Still does. I wondered if I was one, a special boy with special powers because I knew Mr. Petey. I reveled in talking with Mr. Petey. You can’t find a PM stuffed animal, so I made drawings, and my mother sewed me one. I still have it, Petey’s head flops down after all these years. Mr. Petey has seen it all—Mr. Petey, plural. I didn’t know then that he/she lives only one year. A PM’s short life span fundamentally defies the value of human longevity, its evolutionary merit. The flaws therein.

I must’ve fooled myself—actually, kids don’t fool themselves—when a new PM showed up, because their markings and colors vary. I don’t know what I thought. But a PM arrived in the spring and stayed through summer, I called him/her Mr. Petey, and then one day Mr. Petey went for a vacation, in the South. I figured that out for myself. And that was always Mr. Petey in the backyard, until I left home.

I was a dreamy kid. I’m not so dreamy now. Maybe I am still, but in a different way, and my dreaminess is more blocked to me. Or it was, until recently. Anyway, I had dreamed about being a medical doctor because of Dad’s brother Lionel. He told me people wore green uniforms in the hospital. I figured he jumped around in the halls like a big insect, the way he did in our house. But older bro Hart went into medicine, so that got taken. When Uncle Lionel was drunk, he lunged at the couch, collapsed, and slept like the dead until he was pulled off by his wife (Aunt Marnie). My father drank too, but held it better, and he was an estate lawyer.

Lionel took the big hit, a onetime muscle-destroying heart attack. My miserable father battled esophageal cancer. People mostly lose this one, and eventually he did too, not so long ago. Through his breathing tube, Dad spat out his last words to me. Nothing spiritual from an estate lawyer: Get your money out of the market. I almost forgave him for that, later.

I’m so running ahead of myself.

1) Not a good time in my life. In most ways, not.

2) Could be exciting, if it weren’t my life.

3) Studying people’s lives, beliefs, customs. A cultural anthropologist, ethnographer of images.

4) Things shifted—I became my own subject. A soft science, Hart says. “Not putting it down, Little Bro.” He’s four years older and a forensic pathologist. Right, Big Bro, I say, and you see dead people. Actually, dead people have a lot of currency in my family. Our family house was a large 1960s split-level ranch: four bedrooms, parents on one end, children the other, bedrooms the same size for Hart and me and baby sister Clover—but hers had more windows, a sore point—and there were walls of picture windows in the living- and dining-room areas, slate floors, an open kitchen with an island, floor-to-ceiling stone fireplace, and we were sort of in the country. Outside Boston, near Beverly. John Updike territory. Nice family place, if you didn’t know the family. Just kidding. My parents told stories of their upbringings, to the point where they couldn’t make sense of them, or why they were telling them. Reminding them: They shouldn’t have had children. Three of us. “But we had you. We love you.” They were older parents, who waited until the best time, they said, to have the best children. With all that pimping, they underlined their gene-carriers’ supposed exceptionalism by bestowing us with “unique monikers.” I’m Ezekiel (after Dad’s uncle and also a sixth-century prophet) Hooper (maternal surname) Stark (paternal German-Jewish-English-Unitarian). In grade school, “Zeke” was yucky, “Stark” sucky, I rhymed with everything. Brother Hart Hooper Stark, same rhymey biz, but he glories in it, imagines he’s special, like Hart Crane, the writer. But he’s just a pathologist. Our Clover (Clover Sturgis Hooper Stark) doesn’t say anything about her handle, or if she suffers because of its sad legacy (I do). She suffers from selective mutism. She can talk, but she doesn’t want to, or she chooses to be silent—and it’s debatable, maybe she doesn’t choose. She’s six years younger. Ten years younger than Hart. That’s a big spread. Clover’s a singular presence in our midst. Sascha Braunig, Lashes, 2011, oil on panel over canvas, 22 x 18 inches. Courtesy of Foxy Production, New York. Cultural anthropology—my branch, ethnography—isn’t a 19th-century discipline anymore. There’s rigor, or solemnity, about approach and methodology, but there are questions and restiveness in this very divided field about recording subject/object relationships, objectivity itself, which was challenged especially with poststructuralism; and the field’s been dug up, blasted, and basically either lies in ruins or doesn’t, or it’s helped by its differences. I specialize in media, especially photography, also in family, sexual/gender behavior, and relationships as understood through images. I’m an associate professor at a northeastern university, gaming for tenure, and if I play my cards right (and don’t piss off the moribund in my department), it will happen. Cultural studies scored big during the 1990s; since then, the academy’s star is anybody’s guessing game. But no Sundays off in our post-60s academic and not-so-academic civil wars. A cultural anthropologist reflects on differences, similarities, patterns, problems, gathers information; we look at how human beings act and ask why, about others and ourselves. The native is no “primitive,” maybe never but certainly not now; we can be any “we”—whoever we are. “We” can all be subjects and objects of investigation. And are. Then the variations—everything and everyone’s being studied, from Tokyo, Sydney, London, to Borneo and back. In the midst of the field’s epistemological crisis, I am breaking away. Or coming to terms with myself. Almost kidding. (Because there’s no strict separation between “us” and “them,” I’ve started observing my posse and me, guys 30 to 40, and our attitudes toward women.) What you study is informed by yourself. Or, them isn’t a “them”; there’s an interaction. Because how you arrive at the information is also a matter of interaction and perspective. It’s a genuine question, how you behave with your informants; it’s about trust but also the ethnographer can’t trust that he or she knows exactly the motivations for cooperation. I’ve worked with family photographs since grad school. Why do people open their doors and let you in, why do they answer questions, what’s at stake in their lives. Then: Why am I interested in this? What’s my stake in it? All portraits are self-portraits. The world is wired, and remote has several meanings. So, a so-called native informant—a “native” is also an upstate New York gang member—is not an innocent informant. No one’s innocent. The most obvious stuff wasn’t 60 or 70 years ago, and new-style obviousness hides in blatant plain sight. Many humanists and social scientists are incensed—everyone appears to be incensed—about the loss of objectivity and Truth with a cap T. It’s not the end of Western civ. Or maybe it is. As part of my investigations of self and posse, I’ve quizzed myself on what actions I’d take in various circumstances: What if I lost my home and had to live on the streets? What if, before the pill, I’d gotten a girl pregnant, say, in the 1950s. Would I have married her? Or, if an invading army—drones flying low, monster submarines rising at Boston Harbor—had troops landing on the beaches, would I fight? I think I would. But first I’d hide. Then, when they came near my house, I’d fight. Still, by then it might be over. At first I think there would be a warning, along with some panic, but I’d have bought an Uzi or another attack gun. Maybe my posse—all the guys in my sample— would launch into guerrilla action; maybe I’d be solid with fighting building to building, block to block. What about our other friends and families, what happens… At this, I stop imagining and shake my head. The point is, I don’t want to be taken over. The questions propelling my curiosity about others—their images and mine—are the bits I recognize and also don’t recognize in myself, but which filter my narrative, my lopsided tale of self. Self-defining, self-mystifying, and mythologizing. I still know when I’m blowing smoke. Some, like me, use self-denigration as a way to rise up. But when your story goes passive, I mean, when it’s changed on you, that’s a different condition: What happens to you when you are no longer the agent of your story? Along with Mr. Petey, other small creatures, outer space, rockets, robots, and cloud formations, the family photos, movies, and videos were my early obsessions. I classified and did my best to preserve them. My library-making was a formative experience, and a secret world only I understood, with a system I alone knew, because I conceived of it. I stored and preserved (or thought I did) how I wanted. Martin Scorsese says preservation is filmmaking. Think about how much of existence goes into preserving what could instantly disappear, and maybe should, like taking a photo at a wedding. Good or bad? Which is important, the moment or the memorialization? I named my cataloguing system “Zekabet,” coding by colors and numbers and symbols I liked. Naturally, the praying mantis was significant. My color was dark green, like Petey’s; any home video or Super 8 I appeared in was marked with a dark green Crayola. If I shot it, it was marked with lime-green Crayola, and any green was number one. Hart was shit-brown, Clover violet, my mother gray-blue (heavy weather), my father alcohol-red. These accorded with their temperaments and behavior. (My mother once wore a mood ring; it made an impact.) The code never left my pocket. My biggest problem was how to show the passage of time, except by dates, like the year, say, 1989. Too easily decoded. So I created a calendar that related to weather, that is, when it was first recorded in 1880, or “Year 1.” Simple, but cloud formations and movements were also factored in, because I was entranced by clouds and why they took the shapes they did, that they had volume but were made of air, of space. That killed me. Sascha Braunig, Collared, 2011, oil on canvas over wood panel, 24 x 20 inches. Courtesy of Foxy Production, New York. When I wished upon a star, I wished for the preservation of the open-eyed boy I was—to keep him safe, pure, O stars in the sky. In another century, I might have become a castrato, to hold back maturation. I once heard a concert recording of the last-known castrato, made in 1905—totally eerie, his boy voice. I wondered how he had aged, if his face had stayed boyish too. Me, I was a shouter. I’d shout at my parents, who didn’t raise their voices, so that scared them. “I’m not going to grow up like you, I won’t become an adult.” Not unusual for me or America, but I’m nearly 37 (born June 28, 1975). “You’re emotionally immature,” my mother occasionally says, and sister Clover smiles faintly, which pisses me off. But so what. I know I shouldn’t have children. I fell into science, because of insect-interest and cameras, and because of a supercharged madman high school biology teacher, Mr. Adams. He had a purple scar across his forehead from fighting in Vietnam. Hand-to-hand combat, that’s what I pictured. Biology. Math. Chemistry, the warring test tubes. There he was at the front of the classroom. Tall. Strong. Bald. His head framed by the green board, his purple scar scarlet in the sunlight. Not a hero, exactly, but close enough. Mr. Adams. Sort of family, the Adamses, John, Abigail, John Quincy, Henry the historian. Cretins, neurasthenics, criminals, too. I wonder if blood-kin marry idiots and bring them into the family with the intention to destroy the family from within. Hart’s wife is a classic example and should be a case study of the garbage-spouse phenomenon. Life between Hart and me was weird enough, competition, etc., then his wife committed noncriminal-criminal behavior, which occurs regularly in families, where, and nowhere else, things happen or are spoken that would get people incarcerated on the outside, and not just for sexual abuse. In France, they’ve criminalized violent marital verbal abuse; it’s considered as destructive as physical violence, the old sticks and stones can’t hurt your bones but names can never harm you has always been bullshit. The French government may be more worried about violence to the French language than to their people, but I’d argue, with ethno-methodologists like Sacks and Garfinkel, that language is constructing society, inventing it continuously. My dissertation, You’re a Picture, You’re Not a Picture, was pubbed by a good university press when I was 27. “Hot-shot associate prof,” bro’ Hart said. Hot-shit Hart. (But I’m on my third book now, Men in Quotes, and on a sabbatical, sort of.) Hart’s, constitutionally, a weak sadist, no cojones. He’s bad enough, but several assholes have married into the family, and there’s nothing to do about in-laws but despise and ignore them. Clover, at 31, lives at home. With Mother. There’s a picture. In You’re a Picture… I analyzed how families picture themselves through their own photographs, what that picturing implies in terms of association, pecking order, gender relations, etc. I interviewed over 200 families across America, and chose pictures from their albums or let them do the choosing. They told me who was who, what was going on, and weird narratives spilled out. As an ethnographer, I inferred meanings by sorting through the consonances and dissonances, and what the gaps meant, if anything. There’s not much a picture can actually tell you. You can’t read an expression as a permanent response or effect of anything or anyone. A family’s secrets may appear as absences and exclusion. A first marriage was annulled: no pix. A child given up for adoption, no pix of the pregnant mother. The not-there unpictured life, or invisible story, hangs around, along with the silent conversation of nonspeaking pictures. Sometimes the inability to see can be in the self. I call it the Fault Dear Brutus syndrome. In the early 1990s, I saw an exhibition of photographs curated by an African-American photographer from Mississippi. She had asked “black folk” (her term) to lend her their photo albums, then selected and printed photographs, their photos of themselves. Weddings, fooling around, hanging out. Not soul-sad, so-called vérité images of “oppressed black folk” that professionals “captured” on visits South. HUGE impact on me. Documentary photography performed itself, whatever its subject; its mission was to photograph “others.” This doomed their subjects to objecthood, to an “authentic inauthenticity.” That’s my term. That exhibition encouraged me to write my dissertation on family-made images, my own family’s included. Some shit hit the fan, before I earned my doctorate, after my article appeared in Contemporary American Cultural Artifacts, “Documents of Authentic Inauthenticity.” I could have dropped out of sight then, rather than later. But fortunately my thesis director was sympathetic. Also things were changing, and do change. I know that. A viewer can’t tell a documentary photo or movie from a gallery art image or a narrative film. The genre has embraced its inherent fiction-making. There also used to be a claim: artists make art from chaos. Which is funny, to me. 1) Chaotic people make chaos, which they can’t unmake.

2) Chaos is the Real, and totally unavailable. From my POV, storytelling IS ethnography. Some study society in its smallest gestures, conversations, for instance, those guys Harold Garfinkel and Harvey Sacks. I’m down with that. I hear society singing (just kidding) when people gather. And shoot people. Just kidding. Every word in a conversation glues society or tears it. Niceties and social customs are more than niceties—don’t say hello to your mail carrier today. See what happens. I argued, in my second book, Speaking in Plain Sight, that a family photo album effects a silent conversation, one that constitutes an unspoken familial narrative, which adds to what’s reported from sib to sib, generation to generation. But it’s the image of the family that’s built by a combo of words and pix. For this book, I didn’t interview families, I grabbed images from the net and read them only as pictures: formal in terms of composition, how the image was constructed, etc., and as interpretation, what they projected. Also, I considered what the models were from art, movies, etc., for their compositions and meanings, and also from earlier albums. I did a semiotic breakdown of how the images were constructed. I’m curious about whether image itself dominated a person or family’s sense of itself. As in, “upholding the image of the family,” which needs to be learned, and is what my mother hoped to teach me. Society’s an image of itself. It’s impossible to extract, separate, or pull out images, in all their varieties and senses, from how we see and act; to think about how they shape us, because they do. Image is a mental activity. They picture us to us. Pix R us. At 15, I wanted to kill Bro Hart and my father. Figuratively. Most days. I was born into late punk. Say, I was second-generation punk, with some heavy metal and Kurt Cobain and alt-rock thrown in. Being enraged by everything and everyone around me, I was also just a teenager. It’s normal, my mother told me. Hormones, etc. Normal is on a continuum between insanity and sanity, but who defines those degrees and what they mean, family to family. Hell. Barely sane, functionally insane, frequently sane, infrequently insane, moderately sane—THIS PERSON COULD GO EITHER WAY, worse than but approximating normal. I remember asking my mother what her work was, because I knew she wasn’t a housewife: “No woman in her right mind would be a housewife,” she’d said at dinner to Great-Uncle Zeke. He was drunk, laughed it off. It made an impression on me, in 1983 or so. From the 60s through the 80s, mostly educated, articulate, frustrated, despairing, ill-treated women, who were housewives or not, voiced those kinds of positions. Second-wave feminism. My mother never believed women were inferior to men. (Even imagining my mother as inferior is wack.) But women bought it, she said. And for many, there wasn’t the same urge to overcome what she and others felt was injustice. Personal loss. But she told me that people can’t lose what they never had, a statement also pertaining to me and my narrative in a crucial way. My father claimed he was a male feminist; I knew he was a condescending asshole. When Great-Uncle Ezekiel, the one who was totally ignorant about women, and his brothers were kids, they made up their own basketball team in the Not-So-Tall League (they were all under five feet nine inches). There are six photos of the team. As I said, I’m named after Great-Uncle Ezekiel—they say he guarded like a wild dog. When I visualize my namesake, I see a smile and a robust body, and I always ask myself: Could Great-Uncle Ezekiel have had any kind of a sex life? I don’t know why they named me after him; I’m not like him, according to my mother, but l feel implicated in his sexual ignorance. Families do that, implicate you in them. When I think about Great-Uncle Ezekiel’s shock at seeing his blushing bride, Margaret, on the can for the first time, I imagine a snapshot that could be in our family album, but never would be—the unrecorded image, one of the awkward notes of life, always unpictured. Or if pictured, they’re not in family albums. See Weegee, for pictures of the unwanted, unpictured life, and remember the Ouija board. They say you can’t know the other; the family is other; the other is in you, and you can’t know yourself, mostly you can’t, because of how you’re inhabited by others. And sometimes you don’t want to know the other or yourself. I’m so there.

2) Could be exciting, if it weren’t my life.

3) Studying people’s lives, beliefs, customs. A cultural anthropologist, ethnographer of images.

4) Things shifted—I became my own subject. A soft science, Hart says. “Not putting it down, Little Bro.” He’s four years older and a forensic pathologist. Right, Big Bro, I say, and you see dead people. Actually, dead people have a lot of currency in my family. Our family house was a large 1960s split-level ranch: four bedrooms, parents on one end, children the other, bedrooms the same size for Hart and me and baby sister Clover—but hers had more windows, a sore point—and there were walls of picture windows in the living- and dining-room areas, slate floors, an open kitchen with an island, floor-to-ceiling stone fireplace, and we were sort of in the country. Outside Boston, near Beverly. John Updike territory. Nice family place, if you didn’t know the family. Just kidding. My parents told stories of their upbringings, to the point where they couldn’t make sense of them, or why they were telling them. Reminding them: They shouldn’t have had children. Three of us. “But we had you. We love you.” They were older parents, who waited until the best time, they said, to have the best children. With all that pimping, they underlined their gene-carriers’ supposed exceptionalism by bestowing us with “unique monikers.” I’m Ezekiel (after Dad’s uncle and also a sixth-century prophet) Hooper (maternal surname) Stark (paternal German-Jewish-English-Unitarian). In grade school, “Zeke” was yucky, “Stark” sucky, I rhymed with everything. Brother Hart Hooper Stark, same rhymey biz, but he glories in it, imagines he’s special, like Hart Crane, the writer. But he’s just a pathologist. Our Clover (Clover Sturgis Hooper Stark) doesn’t say anything about her handle, or if she suffers because of its sad legacy (I do). She suffers from selective mutism. She can talk, but she doesn’t want to, or she chooses to be silent—and it’s debatable, maybe she doesn’t choose. She’s six years younger. Ten years younger than Hart. That’s a big spread. Clover’s a singular presence in our midst. Sascha Braunig, Lashes, 2011, oil on panel over canvas, 22 x 18 inches. Courtesy of Foxy Production, New York. Cultural anthropology—my branch, ethnography—isn’t a 19th-century discipline anymore. There’s rigor, or solemnity, about approach and methodology, but there are questions and restiveness in this very divided field about recording subject/object relationships, objectivity itself, which was challenged especially with poststructuralism; and the field’s been dug up, blasted, and basically either lies in ruins or doesn’t, or it’s helped by its differences. I specialize in media, especially photography, also in family, sexual/gender behavior, and relationships as understood through images. I’m an associate professor at a northeastern university, gaming for tenure, and if I play my cards right (and don’t piss off the moribund in my department), it will happen. Cultural studies scored big during the 1990s; since then, the academy’s star is anybody’s guessing game. But no Sundays off in our post-60s academic and not-so-academic civil wars. A cultural anthropologist reflects on differences, similarities, patterns, problems, gathers information; we look at how human beings act and ask why, about others and ourselves. The native is no “primitive,” maybe never but certainly not now; we can be any “we”—whoever we are. “We” can all be subjects and objects of investigation. And are. Then the variations—everything and everyone’s being studied, from Tokyo, Sydney, London, to Borneo and back. In the midst of the field’s epistemological crisis, I am breaking away. Or coming to terms with myself. Almost kidding. (Because there’s no strict separation between “us” and “them,” I’ve started observing my posse and me, guys 30 to 40, and our attitudes toward women.) What you study is informed by yourself. Or, them isn’t a “them”; there’s an interaction. Because how you arrive at the information is also a matter of interaction and perspective. It’s a genuine question, how you behave with your informants; it’s about trust but also the ethnographer can’t trust that he or she knows exactly the motivations for cooperation. I’ve worked with family photographs since grad school. Why do people open their doors and let you in, why do they answer questions, what’s at stake in their lives. Then: Why am I interested in this? What’s my stake in it? All portraits are self-portraits. The world is wired, and remote has several meanings. So, a so-called native informant—a “native” is also an upstate New York gang member—is not an innocent informant. No one’s innocent. The most obvious stuff wasn’t 60 or 70 years ago, and new-style obviousness hides in blatant plain sight. Many humanists and social scientists are incensed—everyone appears to be incensed—about the loss of objectivity and Truth with a cap T. It’s not the end of Western civ. Or maybe it is. As part of my investigations of self and posse, I’ve quizzed myself on what actions I’d take in various circumstances: What if I lost my home and had to live on the streets? What if, before the pill, I’d gotten a girl pregnant, say, in the 1950s. Would I have married her? Or, if an invading army—drones flying low, monster submarines rising at Boston Harbor—had troops landing on the beaches, would I fight? I think I would. But first I’d hide. Then, when they came near my house, I’d fight. Still, by then it might be over. At first I think there would be a warning, along with some panic, but I’d have bought an Uzi or another attack gun. Maybe my posse—all the guys in my sample— would launch into guerrilla action; maybe I’d be solid with fighting building to building, block to block. What about our other friends and families, what happens… At this, I stop imagining and shake my head. The point is, I don’t want to be taken over. The questions propelling my curiosity about others—their images and mine—are the bits I recognize and also don’t recognize in myself, but which filter my narrative, my lopsided tale of self. Self-defining, self-mystifying, and mythologizing. I still know when I’m blowing smoke. Some, like me, use self-denigration as a way to rise up. But when your story goes passive, I mean, when it’s changed on you, that’s a different condition: What happens to you when you are no longer the agent of your story? Along with Mr. Petey, other small creatures, outer space, rockets, robots, and cloud formations, the family photos, movies, and videos were my early obsessions. I classified and did my best to preserve them. My library-making was a formative experience, and a secret world only I understood, with a system I alone knew, because I conceived of it. I stored and preserved (or thought I did) how I wanted. Martin Scorsese says preservation is filmmaking. Think about how much of existence goes into preserving what could instantly disappear, and maybe should, like taking a photo at a wedding. Good or bad? Which is important, the moment or the memorialization? I named my cataloguing system “Zekabet,” coding by colors and numbers and symbols I liked. Naturally, the praying mantis was significant. My color was dark green, like Petey’s; any home video or Super 8 I appeared in was marked with a dark green Crayola. If I shot it, it was marked with lime-green Crayola, and any green was number one. Hart was shit-brown, Clover violet, my mother gray-blue (heavy weather), my father alcohol-red. These accorded with their temperaments and behavior. (My mother once wore a mood ring; it made an impact.) The code never left my pocket. My biggest problem was how to show the passage of time, except by dates, like the year, say, 1989. Too easily decoded. So I created a calendar that related to weather, that is, when it was first recorded in 1880, or “Year 1.” Simple, but cloud formations and movements were also factored in, because I was entranced by clouds and why they took the shapes they did, that they had volume but were made of air, of space. That killed me. Sascha Braunig, Collared, 2011, oil on canvas over wood panel, 24 x 20 inches. Courtesy of Foxy Production, New York. When I wished upon a star, I wished for the preservation of the open-eyed boy I was—to keep him safe, pure, O stars in the sky. In another century, I might have become a castrato, to hold back maturation. I once heard a concert recording of the last-known castrato, made in 1905—totally eerie, his boy voice. I wondered how he had aged, if his face had stayed boyish too. Me, I was a shouter. I’d shout at my parents, who didn’t raise their voices, so that scared them. “I’m not going to grow up like you, I won’t become an adult.” Not unusual for me or America, but I’m nearly 37 (born June 28, 1975). “You’re emotionally immature,” my mother occasionally says, and sister Clover smiles faintly, which pisses me off. But so what. I know I shouldn’t have children. I fell into science, because of insect-interest and cameras, and because of a supercharged madman high school biology teacher, Mr. Adams. He had a purple scar across his forehead from fighting in Vietnam. Hand-to-hand combat, that’s what I pictured. Biology. Math. Chemistry, the warring test tubes. There he was at the front of the classroom. Tall. Strong. Bald. His head framed by the green board, his purple scar scarlet in the sunlight. Not a hero, exactly, but close enough. Mr. Adams. Sort of family, the Adamses, John, Abigail, John Quincy, Henry the historian. Cretins, neurasthenics, criminals, too. I wonder if blood-kin marry idiots and bring them into the family with the intention to destroy the family from within. Hart’s wife is a classic example and should be a case study of the garbage-spouse phenomenon. Life between Hart and me was weird enough, competition, etc., then his wife committed noncriminal-criminal behavior, which occurs regularly in families, where, and nowhere else, things happen or are spoken that would get people incarcerated on the outside, and not just for sexual abuse. In France, they’ve criminalized violent marital verbal abuse; it’s considered as destructive as physical violence, the old sticks and stones can’t hurt your bones but names can never harm you has always been bullshit. The French government may be more worried about violence to the French language than to their people, but I’d argue, with ethno-methodologists like Sacks and Garfinkel, that language is constructing society, inventing it continuously. My dissertation, You’re a Picture, You’re Not a Picture, was pubbed by a good university press when I was 27. “Hot-shot associate prof,” bro’ Hart said. Hot-shit Hart. (But I’m on my third book now, Men in Quotes, and on a sabbatical, sort of.) Hart’s, constitutionally, a weak sadist, no cojones. He’s bad enough, but several assholes have married into the family, and there’s nothing to do about in-laws but despise and ignore them. Clover, at 31, lives at home. With Mother. There’s a picture. In You’re a Picture… I analyzed how families picture themselves through their own photographs, what that picturing implies in terms of association, pecking order, gender relations, etc. I interviewed over 200 families across America, and chose pictures from their albums or let them do the choosing. They told me who was who, what was going on, and weird narratives spilled out. As an ethnographer, I inferred meanings by sorting through the consonances and dissonances, and what the gaps meant, if anything. There’s not much a picture can actually tell you. You can’t read an expression as a permanent response or effect of anything or anyone. A family’s secrets may appear as absences and exclusion. A first marriage was annulled: no pix. A child given up for adoption, no pix of the pregnant mother. The not-there unpictured life, or invisible story, hangs around, along with the silent conversation of nonspeaking pictures. Sometimes the inability to see can be in the self. I call it the Fault Dear Brutus syndrome. In the early 1990s, I saw an exhibition of photographs curated by an African-American photographer from Mississippi. She had asked “black folk” (her term) to lend her their photo albums, then selected and printed photographs, their photos of themselves. Weddings, fooling around, hanging out. Not soul-sad, so-called vérité images of “oppressed black folk” that professionals “captured” on visits South. HUGE impact on me. Documentary photography performed itself, whatever its subject; its mission was to photograph “others.” This doomed their subjects to objecthood, to an “authentic inauthenticity.” That’s my term. That exhibition encouraged me to write my dissertation on family-made images, my own family’s included. Some shit hit the fan, before I earned my doctorate, after my article appeared in Contemporary American Cultural Artifacts, “Documents of Authentic Inauthenticity.” I could have dropped out of sight then, rather than later. But fortunately my thesis director was sympathetic. Also things were changing, and do change. I know that. A viewer can’t tell a documentary photo or movie from a gallery art image or a narrative film. The genre has embraced its inherent fiction-making. There also used to be a claim: artists make art from chaos. Which is funny, to me. 1) Chaotic people make chaos, which they can’t unmake.

2) Chaos is the Real, and totally unavailable. From my POV, storytelling IS ethnography. Some study society in its smallest gestures, conversations, for instance, those guys Harold Garfinkel and Harvey Sacks. I’m down with that. I hear society singing (just kidding) when people gather. And shoot people. Just kidding. Every word in a conversation glues society or tears it. Niceties and social customs are more than niceties—don’t say hello to your mail carrier today. See what happens. I argued, in my second book, Speaking in Plain Sight, that a family photo album effects a silent conversation, one that constitutes an unspoken familial narrative, which adds to what’s reported from sib to sib, generation to generation. But it’s the image of the family that’s built by a combo of words and pix. For this book, I didn’t interview families, I grabbed images from the net and read them only as pictures: formal in terms of composition, how the image was constructed, etc., and as interpretation, what they projected. Also, I considered what the models were from art, movies, etc., for their compositions and meanings, and also from earlier albums. I did a semiotic breakdown of how the images were constructed. I’m curious about whether image itself dominated a person or family’s sense of itself. As in, “upholding the image of the family,” which needs to be learned, and is what my mother hoped to teach me. Society’s an image of itself. It’s impossible to extract, separate, or pull out images, in all their varieties and senses, from how we see and act; to think about how they shape us, because they do. Image is a mental activity. They picture us to us. Pix R us. At 15, I wanted to kill Bro Hart and my father. Figuratively. Most days. I was born into late punk. Say, I was second-generation punk, with some heavy metal and Kurt Cobain and alt-rock thrown in. Being enraged by everything and everyone around me, I was also just a teenager. It’s normal, my mother told me. Hormones, etc. Normal is on a continuum between insanity and sanity, but who defines those degrees and what they mean, family to family. Hell. Barely sane, functionally insane, frequently sane, infrequently insane, moderately sane—THIS PERSON COULD GO EITHER WAY, worse than but approximating normal. I remember asking my mother what her work was, because I knew she wasn’t a housewife: “No woman in her right mind would be a housewife,” she’d said at dinner to Great-Uncle Zeke. He was drunk, laughed it off. It made an impression on me, in 1983 or so. From the 60s through the 80s, mostly educated, articulate, frustrated, despairing, ill-treated women, who were housewives or not, voiced those kinds of positions. Second-wave feminism. My mother never believed women were inferior to men. (Even imagining my mother as inferior is wack.) But women bought it, she said. And for many, there wasn’t the same urge to overcome what she and others felt was injustice. Personal loss. But she told me that people can’t lose what they never had, a statement also pertaining to me and my narrative in a crucial way. My father claimed he was a male feminist; I knew he was a condescending asshole. When Great-Uncle Ezekiel, the one who was totally ignorant about women, and his brothers were kids, they made up their own basketball team in the Not-So-Tall League (they were all under five feet nine inches). There are six photos of the team. As I said, I’m named after Great-Uncle Ezekiel—they say he guarded like a wild dog. When I visualize my namesake, I see a smile and a robust body, and I always ask myself: Could Great-Uncle Ezekiel have had any kind of a sex life? I don’t know why they named me after him; I’m not like him, according to my mother, but l feel implicated in his sexual ignorance. Families do that, implicate you in them. When I think about Great-Uncle Ezekiel’s shock at seeing his blushing bride, Margaret, on the can for the first time, I imagine a snapshot that could be in our family album, but never would be—the unrecorded image, one of the awkward notes of life, always unpictured. Or if pictured, they’re not in family albums. See Weegee, for pictures of the unwanted, unpictured life, and remember the Ouija board. They say you can’t know the other; the family is other; the other is in you, and you can’t know yourself, mostly you can’t, because of how you’re inhabited by others. And sometimes you don’t want to know the other or yourself. I’m so there.