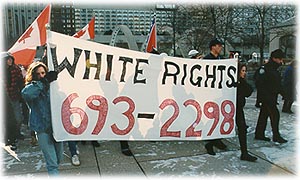

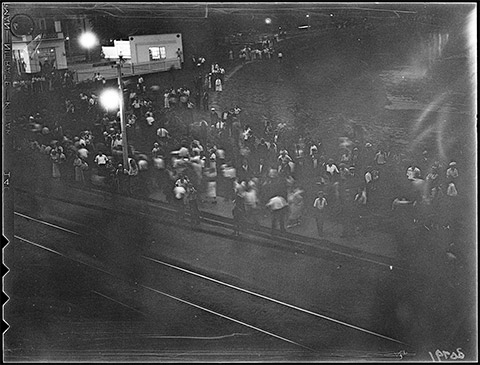

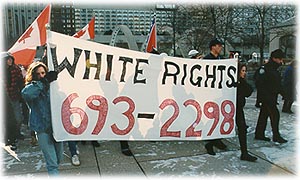

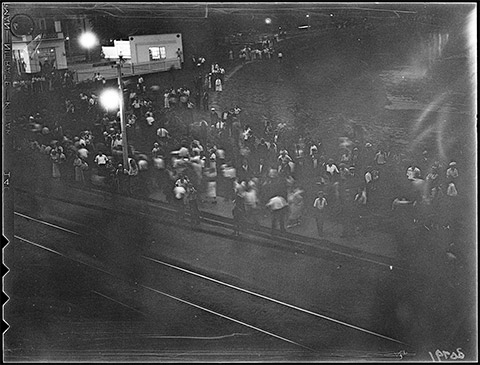

On Wednesday night, longtime leaders of Canada’s white supremacy movement paraded into a Toronto public library to remember a lawyer they considered a hero. In spite of outcry from human rights advocates and calls from the mayor of Toronto to shut it down, they gathered in the name of free expression.Paul Fromm, one of Canada’s most notorious self-identified white nationalists, organized the event as a memorial for lawyer Barbara Kulaszka, who infamously helped alleged war criminals and avowed Holocaust deniers beat criminal charges. Fromm said she died last month of lung cancer. Dressed in a blue-and-white striped summer suit, he spoke with reporters outside the library insisting they are only living out their right to gather in a place they support as taxpaying citizens, insisting they were doing nothing illegal.Fromm is among the old guard of Canada’s far-right. While he and his ilk have been largely ignored in recent years, overshadowed by the rise of the so-called alt-right taken up by younger and more tech-savvy figures, they represent Canada’s sordid — and often overlooked — past with white supremacy.Over the course of the summer, to mark Canada’s 150th birthday, VICE News will be digging into some of the forgotten sagas from the past century-and-a-half. In June, we published the history of the RCMP’s barn-burning tactics to go after the Black Panther Party.By the 1920s, the KKK boasted chapters from B.C. to the Maritimes and enlisted thousands of members — the Saskatchewan group grew to as many as 25,000 people. Their prominence manifested in a number of violent events, including when a small group detonated dynamite in the foyer of a Catholic Church in Barrie, Ontario. Similarly, “Swastika clubs” popped up throughout Toronto as Eastern European immigrants streamed into low-income neighbourhoods. Their legacy is a six-hour brawl that broke out during a baseball game in Christie Pits park in 1933.

Dressed in a blue-and-white striped summer suit, he spoke with reporters outside the library insisting they are only living out their right to gather in a place they support as taxpaying citizens, insisting they were doing nothing illegal.Fromm is among the old guard of Canada’s far-right. While he and his ilk have been largely ignored in recent years, overshadowed by the rise of the so-called alt-right taken up by younger and more tech-savvy figures, they represent Canada’s sordid — and often overlooked — past with white supremacy.Over the course of the summer, to mark Canada’s 150th birthday, VICE News will be digging into some of the forgotten sagas from the past century-and-a-half. In June, we published the history of the RCMP’s barn-burning tactics to go after the Black Panther Party.By the 1920s, the KKK boasted chapters from B.C. to the Maritimes and enlisted thousands of members — the Saskatchewan group grew to as many as 25,000 people. Their prominence manifested in a number of violent events, including when a small group detonated dynamite in the foyer of a Catholic Church in Barrie, Ontario. Similarly, “Swastika clubs” popped up throughout Toronto as Eastern European immigrants streamed into low-income neighbourhoods. Their legacy is a six-hour brawl that broke out during a baseball game in Christie Pits park in 1933. Much like in the U.S., groups like the KKK lost momentum in the post-war period. That is, until the 1960s, when the neo-Nazi skinhead movement took root again and made its way north.Various political organizations, from the Nationalist Party of Canada to the Heritage Front and the Western Guard Party cropped up in the decades that followed, with much of the organization centering around a club house in east Toronto owned by Don Andrews.It was from there that an ambitious plot took shape in the early 80s, with a small group of neo-Nazis and Klansmen from the U.S. and Canada planning a coup against the Caribbean island of Dominica, led in part by German-born Canadian Wolfgang Droege.The plan, detailed in the book Bayou of Pigs, was for the ragtag militia to travel to the small impoverished island from New Orleans and storm the government, armed with automatic weapons and a Nazi flag. They would then set up a white nationalist paradise, funded by gambling and offshore banking.But the FBI dashed their dreams after agents infiltrated and broke up it up in 1981. Droege and a number of other American white supremacists eventually pleaded guilty to a range of criminal offences and served years-long prison terms.The movement then focused on influencing politics closer to home.

Much like in the U.S., groups like the KKK lost momentum in the post-war period. That is, until the 1960s, when the neo-Nazi skinhead movement took root again and made its way north.Various political organizations, from the Nationalist Party of Canada to the Heritage Front and the Western Guard Party cropped up in the decades that followed, with much of the organization centering around a club house in east Toronto owned by Don Andrews.It was from there that an ambitious plot took shape in the early 80s, with a small group of neo-Nazis and Klansmen from the U.S. and Canada planning a coup against the Caribbean island of Dominica, led in part by German-born Canadian Wolfgang Droege.The plan, detailed in the book Bayou of Pigs, was for the ragtag militia to travel to the small impoverished island from New Orleans and storm the government, armed with automatic weapons and a Nazi flag. They would then set up a white nationalist paradise, funded by gambling and offshore banking.But the FBI dashed their dreams after agents infiltrated and broke up it up in 1981. Droege and a number of other American white supremacists eventually pleaded guilty to a range of criminal offences and served years-long prison terms.The movement then focused on influencing politics closer to home. There was also a series of landmark court battles throughout the 1980s and 1990s, with a string of right-wing extremists fighting to defend their ability to spew anti-Semitism and racist propaganda.Kulaszka, the lawyer, cut her teeth defending prolific holocaust denier Ernst Zündel, who was charged with spreading “false news” for publishing the pamphlet: Did Six Million Really Die? That case ultimately made it to the Supreme Court, which acquitted Zündel and struck down the section of the criminal code as unconstitutional.Zündel was eventually deported from Canada as a threat to national security, and later on sentenced to prison by a German court for incitement of hatred.In 1987, Kulaszka defended Imre Finta, a Canadian man and former police officer in Hungary accused of war crimes for helping deport more than 8,600 Jews to Nazi concentration camps. She argued that Canada’s war crimes legislation, under which Finta was being prosecuted, was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court again agreed, and war crime cases now favor deportation proceedings over criminal charges.

There was also a series of landmark court battles throughout the 1980s and 1990s, with a string of right-wing extremists fighting to defend their ability to spew anti-Semitism and racist propaganda.Kulaszka, the lawyer, cut her teeth defending prolific holocaust denier Ernst Zündel, who was charged with spreading “false news” for publishing the pamphlet: Did Six Million Really Die? That case ultimately made it to the Supreme Court, which acquitted Zündel and struck down the section of the criminal code as unconstitutional.Zündel was eventually deported from Canada as a threat to national security, and later on sentenced to prison by a German court for incitement of hatred.In 1987, Kulaszka defended Imre Finta, a Canadian man and former police officer in Hungary accused of war crimes for helping deport more than 8,600 Jews to Nazi concentration camps. She argued that Canada’s war crimes legislation, under which Finta was being prosecuted, was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court again agreed, and war crime cases now favor deportation proceedings over criminal charges. In Alberta, James Keegstra, a Holocaust-denying teacher who also served as a mayor of the small town of Eckville, was charged with hate speech in 1984 after preaching anti-Semitic views to his students. In court, his students would later recount that they were expected to repeat Keegstra’s poorly-sourced historical revisionism, or else their grades would suffer.“I got onto this through scripture,” Keegstra told reporters. “Here was a people who denied everything about Christ, yet they were called the chosen people. That is a contradiction.” He also said that Jews “created the Holocaust to gain sympathy.”The landmark victories failed to galvanize broader support for the movement.In 2005, the Heritage Front — which was supported but not officially joined by Fromm and Zündel — was disbanded by CSIS after an agent infiltrated the group and became one of its leaders. Later that year, founder Droege was shot and killed in Toronto in an apparent drug deal gone bad.Various white nationalist characters launched bids at elected office in recent years but failed to ever garner more than a smattering of votes. Andrews ran from mayor of Toronto in 2014 — telling VICE Canada at the time “not to be a racist is to be an idiot” — and garnered just over 1,000 votes, putting him seventh.In 2007, the House of Commons unanimously passed a resolution banning Fromm and fellow activist Alexan Kulbashian from the Parliament buildings after they attempted to host a press briefing there to vent about the federal human rights commission, which had fined Kulbashian for posting hateful messages about Jews, Muslims, and other minorities online.

In Alberta, James Keegstra, a Holocaust-denying teacher who also served as a mayor of the small town of Eckville, was charged with hate speech in 1984 after preaching anti-Semitic views to his students. In court, his students would later recount that they were expected to repeat Keegstra’s poorly-sourced historical revisionism, or else their grades would suffer.“I got onto this through scripture,” Keegstra told reporters. “Here was a people who denied everything about Christ, yet they were called the chosen people. That is a contradiction.” He also said that Jews “created the Holocaust to gain sympathy.”The landmark victories failed to galvanize broader support for the movement.In 2005, the Heritage Front — which was supported but not officially joined by Fromm and Zündel — was disbanded by CSIS after an agent infiltrated the group and became one of its leaders. Later that year, founder Droege was shot and killed in Toronto in an apparent drug deal gone bad.Various white nationalist characters launched bids at elected office in recent years but failed to ever garner more than a smattering of votes. Andrews ran from mayor of Toronto in 2014 — telling VICE Canada at the time “not to be a racist is to be an idiot” — and garnered just over 1,000 votes, putting him seventh.In 2007, the House of Commons unanimously passed a resolution banning Fromm and fellow activist Alexan Kulbashian from the Parliament buildings after they attempted to host a press briefing there to vent about the federal human rights commission, which had fined Kulbashian for posting hateful messages about Jews, Muslims, and other minorities online. “If they want to get a soapbox and go out in front of the Parliament Buildings in this free country, they’re welcome to do so, but this House isn’t going to let them use public, taxpayer-funded resources,” Conservative MP Jason Kenney said at the time.Back at the Toronto library this week, Fromm said he and his group continue to meet in public spots “around the city” every month, but they usually keep the locations a secret. While he and others said they were angry at attempts to stifle their “right to free speech,” they heralded library staff as “courageous” for allowing them to gather there.Fromm, now in his late 60s, said the opposition to their meeting is indicative of discrimination he faces as someone who holds views considered by most as different or “repugnant.”Fromm, just before entering the library meeting room flanked by security, gave Canada a poor review.“This is not a very nice country.”

“If they want to get a soapbox and go out in front of the Parliament Buildings in this free country, they’re welcome to do so, but this House isn’t going to let them use public, taxpayer-funded resources,” Conservative MP Jason Kenney said at the time.Back at the Toronto library this week, Fromm said he and his group continue to meet in public spots “around the city” every month, but they usually keep the locations a secret. While he and others said they were angry at attempts to stifle their “right to free speech,” they heralded library staff as “courageous” for allowing them to gather there.Fromm, now in his late 60s, said the opposition to their meeting is indicative of discrimination he faces as someone who holds views considered by most as different or “repugnant.”Fromm, just before entering the library meeting room flanked by security, gave Canada a poor review.“This is not a very nice country.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

That was one the far-right lost. The Supreme Court upheld his hate crimes conviction in 1990. Keegstra served a one-year suspended sentence, 200 hours of community service, and a year of probation for the crime.“This is not a very nice country.”

Advertisement