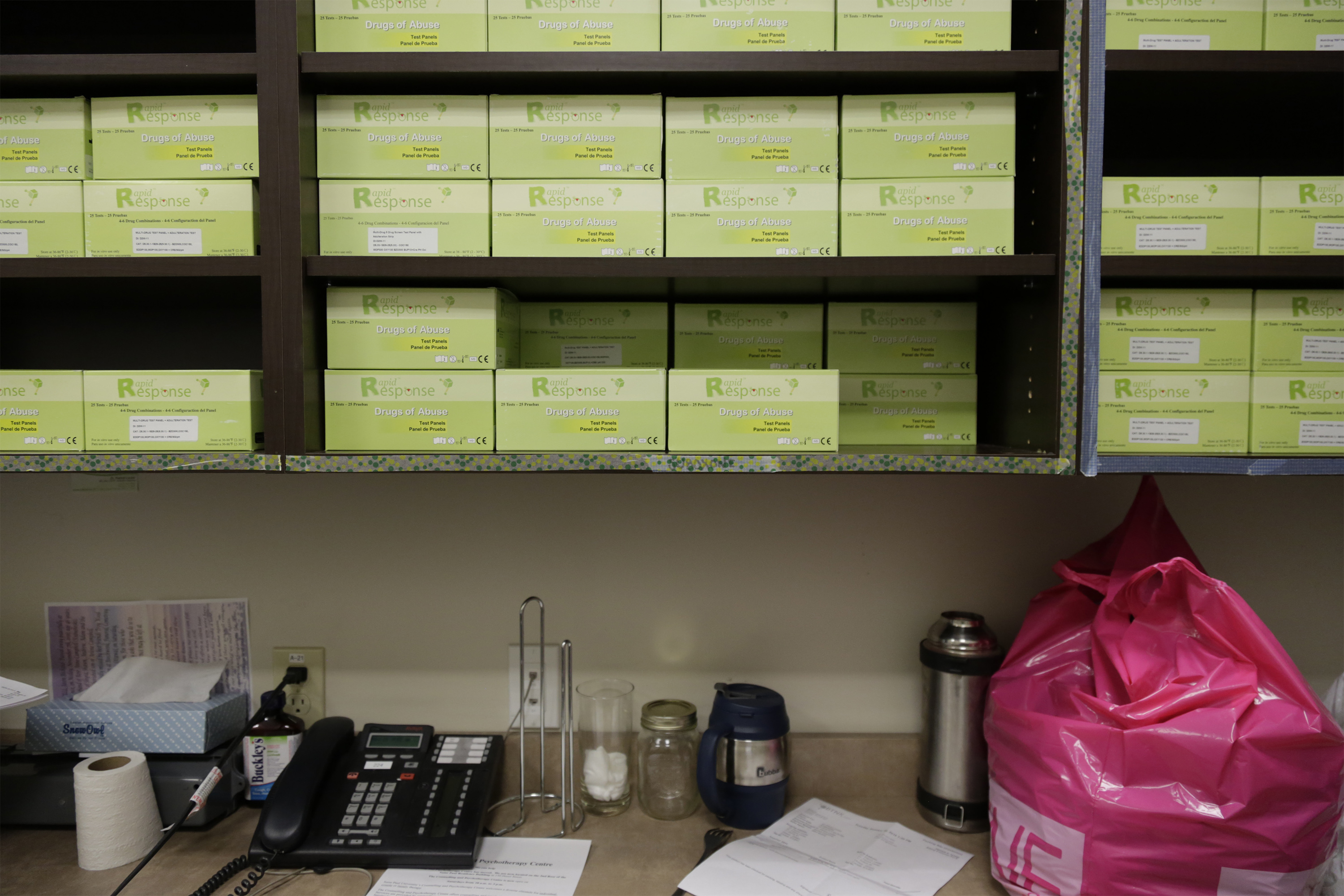

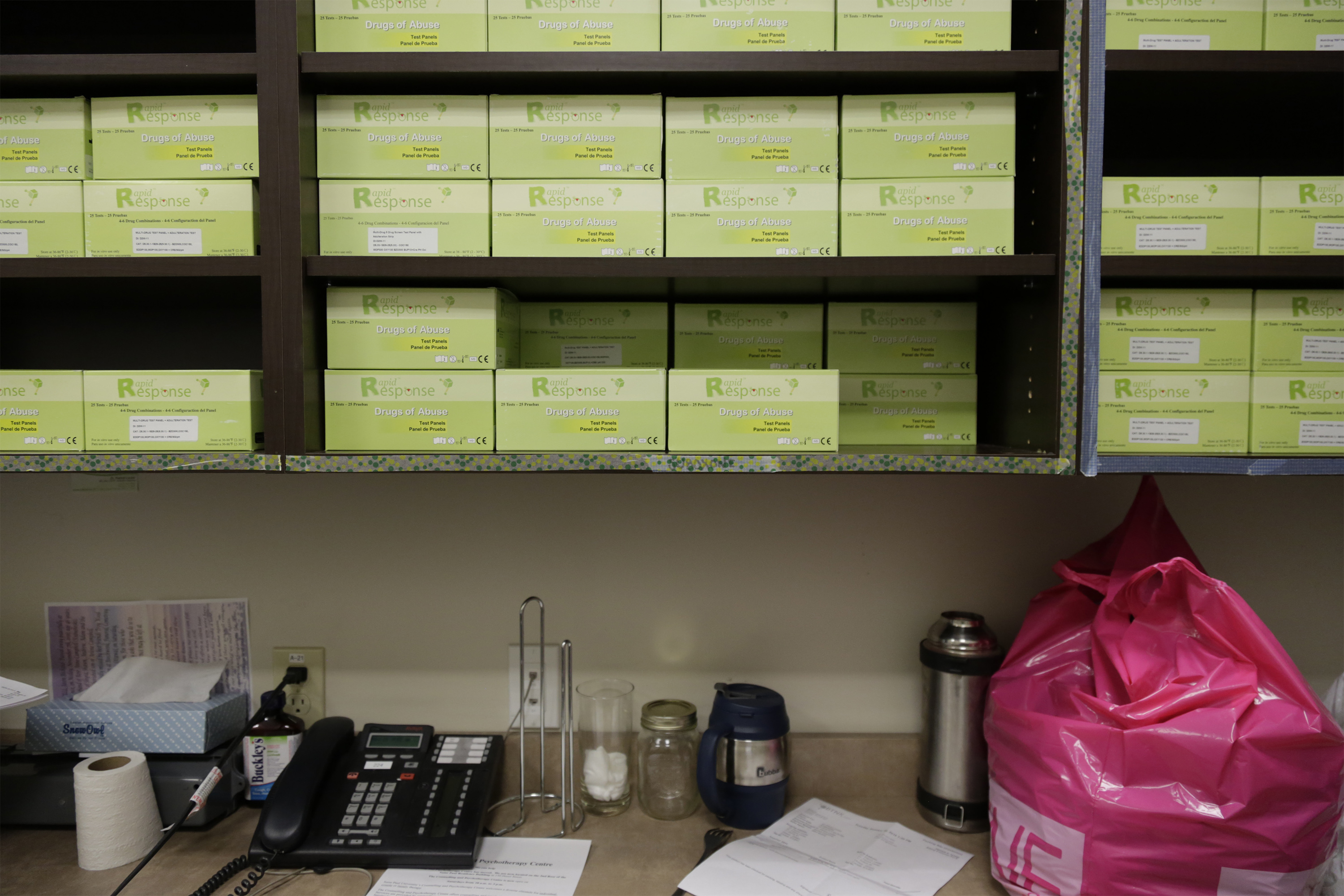

It’s the morning rush at Recovery Ottawa, one of the city’s few clinics that prescribes methadone and suboxone for people addicted to opioids. Patients have until noon to pick up their medicine and there’s a crowd forming by the pharmacy counter near the waiting area. Around 300 patients are expected to show up today. The people in suits on their way to work this Wednesday have already come and gone.“The biggest thing I’ve learned at this job is to never judge someone’s life by how they look,” Samantha, the office administrator, says as she floats through the building located in a strip mall on Selkirk Street. She opens a small door in the wall behind reception and peers into the bathroom on the other side to check that a patient isn’t tampering with his urine sample, something that’s required before people can get the medication that will keep the intense withdrawal symptoms at bay.Ever since the clinic expanded to this spot in 2013, the number of patients has swelled to more than 1,200. It’s a small window into the overdose crisis that has gripped the country for years, but has only recently captured national attention. Later in the week, in a signal of just how much things have escalated, Canada’s health minister will host the first-ever federal opioid summit to address the staggering overdose problem and provide “concrete actions.” But the doctor at the helm here has little hope it will lead to the radical changes he says are desperately needed to save lives. Even mentioning the words “government conference” gets him going.“They should kill the summit, take whatever millions of dollars it all costs, and open real treatment centres,” said Dr. Mark Ujjainwalla. “Open medical detoxes. I don’t see that happening. Let’s call a spade a spade: it’s a waste of time,” he said, noting he wasn’t invited to attend. “No level of government has taken things seriously, and they’ve known how to solve it for years,” he said.The opioid problem is especially difficult to tackle consistently across Canada because, unlike the US, healthcare is a provincial, not federal, responsibility. Although Health Canada can do things like expedite the approvals of craving-curbing drugs like suboxone and also increase funding for addictions and mental health treatment, it’s the provincial governments that decides what their priorities are.

But the doctor at the helm here has little hope it will lead to the radical changes he says are desperately needed to save lives. Even mentioning the words “government conference” gets him going.“They should kill the summit, take whatever millions of dollars it all costs, and open real treatment centres,” said Dr. Mark Ujjainwalla. “Open medical detoxes. I don’t see that happening. Let’s call a spade a spade: it’s a waste of time,” he said, noting he wasn’t invited to attend. “No level of government has taken things seriously, and they’ve known how to solve it for years,” he said.The opioid problem is especially difficult to tackle consistently across Canada because, unlike the US, healthcare is a provincial, not federal, responsibility. Although Health Canada can do things like expedite the approvals of craving-curbing drugs like suboxone and also increase funding for addictions and mental health treatment, it’s the provincial governments that decides what their priorities are. Ujjainwalla’s desk is overflowing with patient files — the people he says provide the real solutions for how the addictions crisis.“Normal people in the real world, not politicians and bureaucrats,” he said. “These people just want to live their lives in peace and tranquility. And when they get sick, they need help and they need it now.”There’s a handwritten list on a bookshelf behind him of the 14 patients who have died in the last three months: overdoses, shot in the head, stabbed for drugs. “This is all because they couldn’t get proper treatment quickly,” said Ujjainwalla. He’s been doing this work for 30 years and says running the methadone clinic is the best way he says he can serve patients in the absence of any treatment programs that guide addicts all the way from medical detox to recovery and beyond.Read VICE Canada’s series Relapse: Facing Canada’s Opioid Crisis.A 32-year-old woman who wishes to be called Emma for fear of being recognized sits across from Ujjainwalla as he fills out her methadone prescription for 60 milligrams a day. She says she started smoking crack at age 12 with her mother and brother, and used heroin for a decade until she started the methadone program in October. Like many patients here, she has hepatitis C, likely contracted from dirty needles or doing sex work to buy drugs.“I’ve lost my children, my job, my home, my soul,” says Emma. “But now with the methadone, I was able to get it immediately here and not wait. It makes me feel normal and think clearly for the first time.” All her lesions and abscesses from injecting have finally healed, she tells Ujjainwalla who flashes a quick smile.

Ujjainwalla’s desk is overflowing with patient files — the people he says provide the real solutions for how the addictions crisis.“Normal people in the real world, not politicians and bureaucrats,” he said. “These people just want to live their lives in peace and tranquility. And when they get sick, they need help and they need it now.”There’s a handwritten list on a bookshelf behind him of the 14 patients who have died in the last three months: overdoses, shot in the head, stabbed for drugs. “This is all because they couldn’t get proper treatment quickly,” said Ujjainwalla. He’s been doing this work for 30 years and says running the methadone clinic is the best way he says he can serve patients in the absence of any treatment programs that guide addicts all the way from medical detox to recovery and beyond.Read VICE Canada’s series Relapse: Facing Canada’s Opioid Crisis.A 32-year-old woman who wishes to be called Emma for fear of being recognized sits across from Ujjainwalla as he fills out her methadone prescription for 60 milligrams a day. She says she started smoking crack at age 12 with her mother and brother, and used heroin for a decade until she started the methadone program in October. Like many patients here, she has hepatitis C, likely contracted from dirty needles or doing sex work to buy drugs.“I’ve lost my children, my job, my home, my soul,” says Emma. “But now with the methadone, I was able to get it immediately here and not wait. It makes me feel normal and think clearly for the first time.” All her lesions and abscesses from injecting have finally healed, she tells Ujjainwalla who flashes a quick smile. Though Emma is off the deadly opioids, she still uses cocaine occasionally, as recently as this Sunday. The roots of her addiction remain intact.“If I could put you into a facility where it was safe housing that would help you with your nutrition, general health, emotional health, all your PTSD stuff, would you go?” Ujjainwalla asks her, already knowing the answer.“In a heartbeat … In Ottawa, personally I don’t know where I would go,” her voice cracks. A few months ago, she attended a weeks-long residential treatment facility in Toronto, but says she still has work to do.Ujjainwalla nods. “People will wait sometimes months to see a doctor, a year to get into treatment, and if you do get in somewhere in Ontario, they’ll kick you out if you show any attitude, that type of stuff,” he said. “Some won’t take you if you’re on suboxone or methadone.”

Though Emma is off the deadly opioids, she still uses cocaine occasionally, as recently as this Sunday. The roots of her addiction remain intact.“If I could put you into a facility where it was safe housing that would help you with your nutrition, general health, emotional health, all your PTSD stuff, would you go?” Ujjainwalla asks her, already knowing the answer.“In a heartbeat … In Ottawa, personally I don’t know where I would go,” her voice cracks. A few months ago, she attended a weeks-long residential treatment facility in Toronto, but says she still has work to do.Ujjainwalla nods. “People will wait sometimes months to see a doctor, a year to get into treatment, and if you do get in somewhere in Ontario, they’ll kick you out if you show any attitude, that type of stuff,” he said. “Some won’t take you if you’re on suboxone or methadone.” While Ontario is widely regarded as having relatively good methadone access, the issue of clinics has been a point of controversy in a number of communities over the years. There are also many doctors across the country, and in the US, who won’t prescribe it out of concern for side effects, or because they don’t feel comfortable doing so.And thousands across the country are kept waiting for access to additional treatment options, unless they have tens of thousands of dollars to pay for private healthcare. Very few health authorities have made any progress rectifying this.There are similar problems for those looking to enter detox programs, often a prerequisite for longer treatment programs. As an exercise to show how difficult it really is out there, Ujjainwalla picks up the phone and calls a local detox facility. He tells the worker on the line that his friend “Jane” is a heroin user in need of urgent care, and asks if they have a bed open.“Listen, I don’t have anything now,” the worker says after putting him on hold for a few seconds. “But if you tell Jane to call us at 1PM, we might be able to get her in this evening. No guarantees.”The worker asks if he can support her in the meantime.“Support her? What does that mean,” he mocks, after he hangs up the phone. “They non-medicalize it. They’re making it sound like her cat died. Support her, give her a hug. What the fuck?”Emma walks up to the pharmacy counter where she’s handed a small cup with her methadone dose cut with orange tang. She chugs it in one gulp and opens her mouth to prove it.“What we all need is immediate access to psychiatrists,” she says heading out the door. “Because when you decide you want help, and you can’t get it, that’s when you just go back to using.”Pain, now 34, started taking Oxycontin off the streets in first year university after his best friend was killed in a car accident. Four years ago he was sentenced to jail for his involvement in a drug deal. He was forced to go through withdrawal there, and started the methadone program after he got out.

While Ontario is widely regarded as having relatively good methadone access, the issue of clinics has been a point of controversy in a number of communities over the years. There are also many doctors across the country, and in the US, who won’t prescribe it out of concern for side effects, or because they don’t feel comfortable doing so.And thousands across the country are kept waiting for access to additional treatment options, unless they have tens of thousands of dollars to pay for private healthcare. Very few health authorities have made any progress rectifying this.There are similar problems for those looking to enter detox programs, often a prerequisite for longer treatment programs. As an exercise to show how difficult it really is out there, Ujjainwalla picks up the phone and calls a local detox facility. He tells the worker on the line that his friend “Jane” is a heroin user in need of urgent care, and asks if they have a bed open.“Listen, I don’t have anything now,” the worker says after putting him on hold for a few seconds. “But if you tell Jane to call us at 1PM, we might be able to get her in this evening. No guarantees.”The worker asks if he can support her in the meantime.“Support her? What does that mean,” he mocks, after he hangs up the phone. “They non-medicalize it. They’re making it sound like her cat died. Support her, give her a hug. What the fuck?”Emma walks up to the pharmacy counter where she’s handed a small cup with her methadone dose cut with orange tang. She chugs it in one gulp and opens her mouth to prove it.“What we all need is immediate access to psychiatrists,” she says heading out the door. “Because when you decide you want help, and you can’t get it, that’s when you just go back to using.”Pain, now 34, started taking Oxycontin off the streets in first year university after his best friend was killed in a car accident. Four years ago he was sentenced to jail for his involvement in a drug deal. He was forced to go through withdrawal there, and started the methadone program after he got out. Finally his dosage arrives in a plastic cup. He’s given a week’s supply and takes a breath of relief. “After about 20 minutes, I just start to feel calm, to feel normal. I can go about my day, go for walks and grocery shop, without having to worry about being out of control,” he said. “Places like this work, why not try to get as many as possible for other addicts?”After seeing about 75 patients, Ujjainwalla sits at his desk and opens his laptop. He has a powerpoint presentation about how to overhaul the system. “It would cost billions to gut it, but in the long-term it would be more effective and humane,” he said.Federal health minister Jane Philpott, along with health authorities across the country, have called for more safe injection sites like Insite in Vancouver, as a key solution to the problem. It’s a proposal that’s discussed at great length at the summit.But Ujjainwalla takes issue with safe injection sites, refusing to use the word “safe” when referring to them. He pulls out his cell phone with a closeup photo of one of his clients, a young girl addicted to heroin with lesions all over her face.“Are you honestly going to tell me to send her to a supervised consumption site? They are a smokescreen to treating the bigger problem, which is the disease of addiction and mental health,” he said. “We have cancer treatment centres, heart institutes, but not much in the way of proper healthcare for addictions.”

Finally his dosage arrives in a plastic cup. He’s given a week’s supply and takes a breath of relief. “After about 20 minutes, I just start to feel calm, to feel normal. I can go about my day, go for walks and grocery shop, without having to worry about being out of control,” he said. “Places like this work, why not try to get as many as possible for other addicts?”After seeing about 75 patients, Ujjainwalla sits at his desk and opens his laptop. He has a powerpoint presentation about how to overhaul the system. “It would cost billions to gut it, but in the long-term it would be more effective and humane,” he said.Federal health minister Jane Philpott, along with health authorities across the country, have called for more safe injection sites like Insite in Vancouver, as a key solution to the problem. It’s a proposal that’s discussed at great length at the summit.But Ujjainwalla takes issue with safe injection sites, refusing to use the word “safe” when referring to them. He pulls out his cell phone with a closeup photo of one of his clients, a young girl addicted to heroin with lesions all over her face.“Are you honestly going to tell me to send her to a supervised consumption site? They are a smokescreen to treating the bigger problem, which is the disease of addiction and mental health,” he said. “We have cancer treatment centres, heart institutes, but not much in the way of proper healthcare for addictions.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

At the summit on Friday, Health Minister Jane Philpott mulled the prospect of declaring a national state of emergency over the opioid crisis.“There’s no question that this is a national public health crisis,” Philpott told reporters. But she said department officials are still studying whether a state of emergency is the right move for the country.“If it’s determined that a declaration … is appropriate and helpful, then certainly we will use all of the tools available,” Philpott said.The conference has been criticized for being heavy on talk of regulations around opioid prescriptions, but not on urgent tasks needed to address accessibility to government-funded addictions treatment and integrating it with primary healthcare.

Over in the methadone clinic’s waiting area, Kennie Pain paces back and forth. An olive green parka is draped over his “Blow Me I’m Irish” t-shirt. He came later than usual to pick up his prescription. The cold sweats have started and he wipes his forehead with the black hand towel around his neck.“I’ve been on this stuff five years, I’ve been clean, but I still get sweaty,” Pain said. He used to go to methadone clinics run by the province, but says he switched because he didn’t feel like people there respected him.“There’s still a huge stigma around addiction, let alone people on methadone,” he explains. “People think, oh you’re just a junkie and that’s it. I still find it hard to admit that to people. People can be so narrow-minded.”

Advertisement