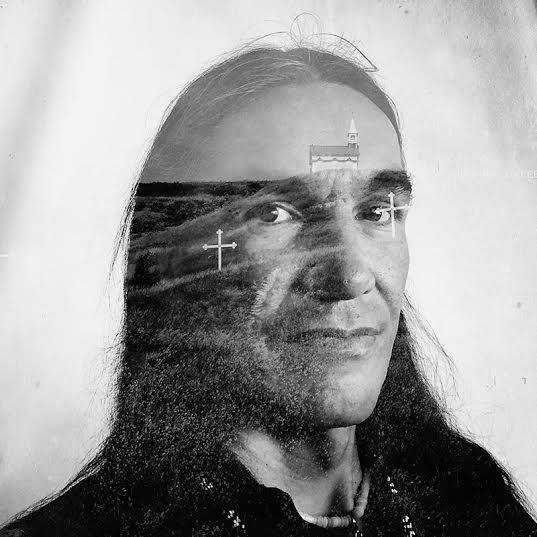

Photo from 'Life After Michael Brown and Freddie Gray': a photographic collaboration between Ferguson-based photographer Michael Thomas and Baltimore-based photographer Glenford Nunez to commemorate the anniversary of the shooting of Michael Brown. Photo edited for Ecosight by Daniella Zalcman

Bradley Cooper reenacts as part of the Essex Second Battalion at the Damyns Hall Aerodrome in 2013. Photo by Daniella Zalcman from 'Sunday Soldiers'

Annie Flanagan: Perhaps because there are not many options for staff positions as a photographer, so we have to seek support networks that are outside certain publications? That was never what I wanted—a staff position—and collectives of all kinds have been a presence in my life for a while now. So, a photography collective has always seemed like an ideal situation.Daniella Zalcman: I don't know that I agreed with that piece, actually. I think, as with every other journalistic institution, they've had to reevaluate and restructure in a lot of ways to keep up with technology and the new/different ways that we interact with media. But newspapers, magazines, wire services, galleries, museums, and publishers have had to do that, too. I don't really feel like the notion of a group of photographers joining together to strengthen each other's visions and brands was ever likely to die out.

Nekqua dances with her twin sibling, Shy. "We have a bond like no other, he is my everything." Photo by Annie Flanagan from 'Hey, Best Friend!' Syracuse, NY, 2012.

For me, one of journalism's best and most noble applications is its ability to elevate oppressed voices. And here is where I start to sound more like an activist than maybe is fashionable, but there are stories where clinical objectivity is absurd. I can pretend all I want that I am approaching stories on the ongoing oppression of sexual minorities from a neutral perspective, but we all know that's bullshit. I do not support anti-homosexuality legislation. I do not support homophobia. I believe that there is a right side of history here, and maybe my work can underscore that too many people, governments, and leaders are on the other side. I think that it is also my job to listen to those voices and do everything I can to represent them honestly and fairly. After three years of documenting Uganda's beleaguered LGBTI community, I realized I'd never made an effort to interact with the 96 percent of the population that supports anti-homosexuality laws; so I reached out to dozens of religious leaders in Kampala to discuss sexual identity, homophobia, and religion with them. While a lot of the conversations were fairly predictable, I was surprised by the number of moderate voices that are often ignored or underrepresented because they don't make for spicy quotes.

We ask a lot of those we photograph and a large part of that is that they be vulnerable. As I began to focus my work on gendered violence and trauma, I found it vital to understand what it was like to document and share my own trauma. And understanding what that vulnerability is like, what it feels like to document and share your own trauma, has made me a more compassionate artist

Lisa practices a hula hoop routine in Runnymede Eco Village, an intentional community that existed in a woodland just outside of London for three years before they were evicted earlier this year. Photo by Daniella Zalcman from 'To Make the Wasteland Grow'

Flanagan: Diversity, and lack thereof, is so important to discuss and we need to fight for the space to discuss and dismantle. It is hard and uncomfortable because it requires that people investigate their own privileges, admit them, and work to dismantle them. It is not a priority for a lot of people. I also think it's hard to discuss because people feel threatened: if you are used to being granted everything based on something that you are born into, if it gets taken away, you tend to do everything to keep it intact. It is going to take a lot of work for both sides—for the oppressed and the oppressors. Coming forward about shit experiences is not easy and can have consequences. Personally, I have had successful dude photographers say shitty things to me because I assume they felt threatened or felt that was their right or did not even understand how misogynistic their speech was. And I hate misogyny.

'My First Black Eye.' Photo by Annie Flanagan from 'We Grew Up With Gum in Our Hair,' Washington, DC, 2006.

Zalcman to Flanagan: I saw the self-portrait of your first black eye a few weeks ago, and it has been ingrained in my memory since. I'm curious about what you think are the strengths and challenges of documenting yourself in such a vulnerable and personal way, and how you think it affects your presentation of a story (and your audience's reaction to that work). I struggle a lot with this in a very different way; I am almost always a complete outsider in my projects, and that's something I'm very self-conscious of and think about constantly. I wonder if the inverse is just as stressful?Flanagan: I am terrified about putting images of my personal life out into the open. Every time I share an image and I am open and honest about my personal life, I do it in complete fear and lack any confidence. We need to understand what we ask of those we photograph—to be vulnerable, to share trauma and other intimacies, to share the healing process. I cannot ask other people to do these things if I am not comfortable doing them myself. If fears of judgement, of safety, were stopping me from being honest, how could I expect others to be honest? This particularly relates to documenting my own trauma and anxiety, but also to sharing images of my friends and relationships. I made a promise to myself that I would not let fear stop me from moving forward or making work or taking risks, so even though I now share work about my life, I do it in fear. I just refuse to let that fear stop me.

Nic. Photo from 'Holding On & Letting Go,' Biloxi, Mississippi, 2015Annie Flanagan

Two girls play outside a hidden LGBTI organization in Kampala, Uganda in January 2014 — just a few weeks after Parliament passed an Anti-Homosexuality Act. Photo from 'We Are Kuchus'Daniella Zalcman

This was the summer of loss and pain. It was hard and unreal but we were there for each other in unhealthy ways. Photo from 'Incredible Maniacs,' Brattleboro, VT, 2014Annie Flanagan