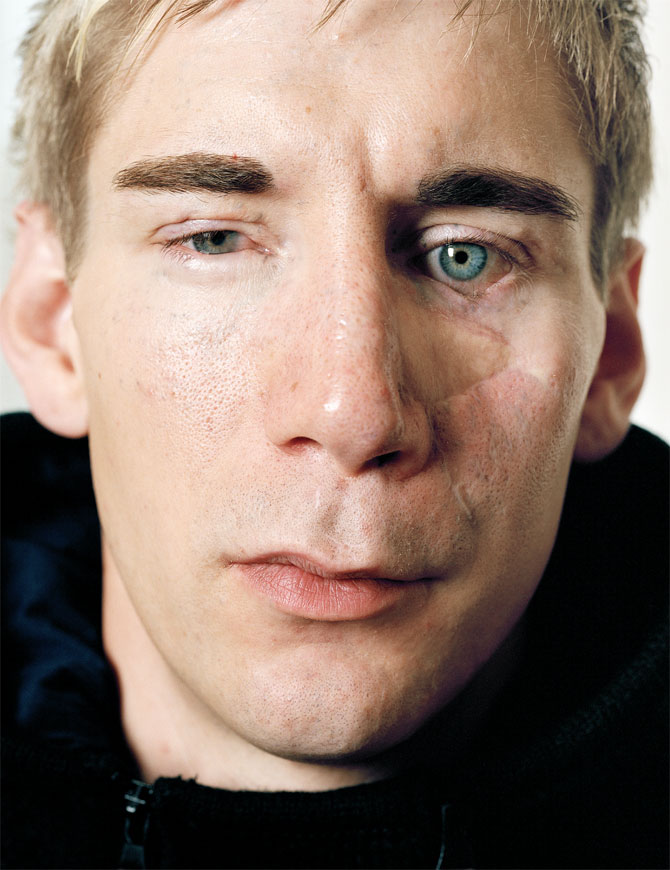

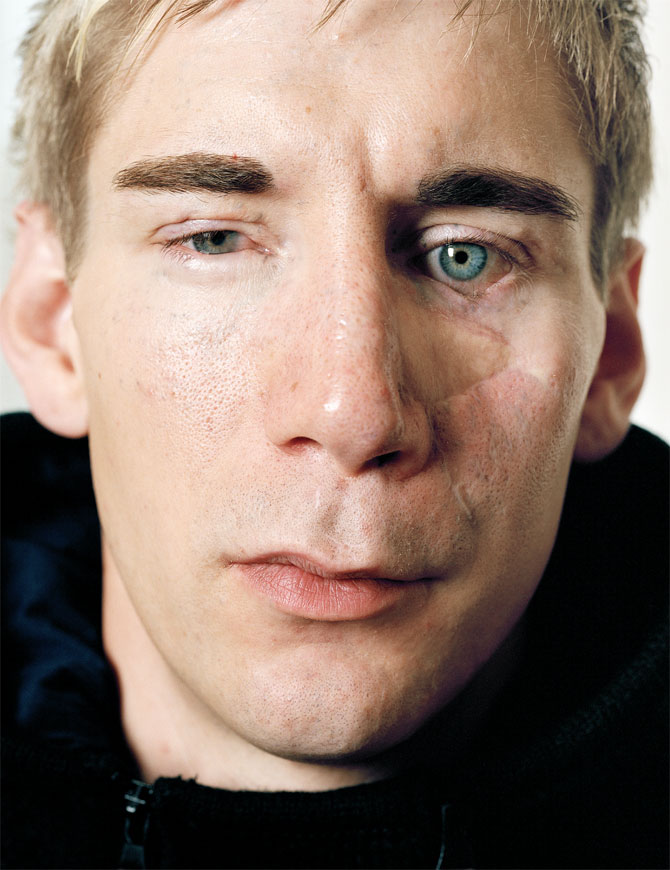

PHOTOS AND TEXT BY STUART GRIFFITHSAndy Julien was 18 years old and had been serving in Iraq for two months with the Queen’s Royal Lancers when his Challenger tank came under fire south of Basra. Andy and Lance Corporal Daniel Twiddy had been asleep on top of the tank when they were attacked. An eyewitness later told a Ministry of Defense board of inquiry that after “the boom of a heavy weapon and a bright flash of light” the tank became “an exploding ball of fire.” Andy and Daniel were thrown to the ground, engulfed in flames. Two of their fellow soldiers were killed inside the tank on impact.Now here’s the really hilarious part: Andy’s tank had come under fire from allied troops. This incident was caused by what was described in the inquiry as a “catalog of errors.” The laws of combat immunity protect the identities of those responsible for the attack, so nobody will be charged. In fact, Andy has heard rumors that since the incident, crew members of the tank that fired on him have been promoted.After mistakenly informing his parents of his death, the Ministry of Defense flew Andy back to Broomfield Hospital in Essex. His mother and father did not initially recognize the swollen, bloody heap of flesh that they were told was their son. After 20 operations and six months in a wheelchair, Andy was medically discharged from the army without even the offer of a desk job.

ive days into the war in Iraq in March 2003, Daniel Twiddy was blown off the top of a Challenger tank outside Basra by a round of friendly fire. It was a 120-millimeter high-explosive squash-head shell from another British tank. He remembers bursting into flames as a second round impacted on the turret of the vehicle, killing two of his colleagues. He also remembers being on his hands and knees, on fire, screaming during what he thought would be the last seconds of his life.He awoke a month later in Broomfield Hospital, Chelmsford. His skin was burned over 80 percent of his body and there was a large hole in his face. He considers himself very lucky.Daniel told Vice, “I’ve been a gunner myself and when you hit hard targets like tanks, it’s unbelievable. 120-millimeter high-explosive squash-heads are designed to destroy bunkers. They fired two. That’s how lucky I was.“When I joined the British Army I respected the Ministry of Defense. I thought that it was their duty to support you through thick and thin. But when you’re at the parade they have for graduation from training and they say, ‘Not only is your son part of our family, you’re all part of our family now,’ it’s bollocks—total shit. As soon as something like what happened to me occurs, they toss you aside like a number. They’re not bothered about you. Physically, I can heal up. What hurts the most is that I’ve been left behind. I’ll always remember what they’ve done to me. Friendly fire is something that should never have happened, so they should be looking after me. But they won’t admit it. That’s what makes me the most angry.”

ive days into the war in Iraq in March 2003, Daniel Twiddy was blown off the top of a Challenger tank outside Basra by a round of friendly fire. It was a 120-millimeter high-explosive squash-head shell from another British tank. He remembers bursting into flames as a second round impacted on the turret of the vehicle, killing two of his colleagues. He also remembers being on his hands and knees, on fire, screaming during what he thought would be the last seconds of his life.He awoke a month later in Broomfield Hospital, Chelmsford. His skin was burned over 80 percent of his body and there was a large hole in his face. He considers himself very lucky.Daniel told Vice, “I’ve been a gunner myself and when you hit hard targets like tanks, it’s unbelievable. 120-millimeter high-explosive squash-heads are designed to destroy bunkers. They fired two. That’s how lucky I was.“When I joined the British Army I respected the Ministry of Defense. I thought that it was their duty to support you through thick and thin. But when you’re at the parade they have for graduation from training and they say, ‘Not only is your son part of our family, you’re all part of our family now,’ it’s bollocks—total shit. As soon as something like what happened to me occurs, they toss you aside like a number. They’re not bothered about you. Physically, I can heal up. What hurts the most is that I’ve been left behind. I’ll always remember what they’ve done to me. Friendly fire is something that should never have happened, so they should be looking after me. But they won’t admit it. That’s what makes me the most angry.”

uring his second tour of Iraq, in 2005, Mark Drydon was on a routine patrol. It was a Sunday. Fridays in Iraq are fairly quiet because everyone goes to mosques. Sunday, for Iraqis, is a fairly normal working day. But on this particular Sunday, it struck Mark that there was no one on the street.Mark told us, “It was like the Iraqi people knew what was going to happen. The road we drove up is usually one of the busiest ones in Basra but there were no kids, no cars, nothing. Suddenly there were two explosions. The first one was in the engine block, and the second came through my door. It all happened in seconds, but everything slowed down from the point of the second explosion going off. I knew I was badly injured. I was sent back to the medical-recovery station in a hotel nearby, where they can stabilize you and get you ready for the helicopter evacuation to the main hospital.“I don’t think that the British public have slagged the army off—they’ve slagged off the government for sending us. Now it’s like, why are we still out there? Why are we still getting killed and injured? I’d already done fighting in Iraq in 2003. I’ve been to Bosnia, Kosovo, and done two tours of Ireland, but I was more scared to go back to Iraq in 2005 than I ever was in my life. I even changed my life insurance and made sure my will was bang up-to-date before I went out there. When I look back to Northern Ireland in the 1970s, Iraq seems very similar. I think we will be there for another 10 or 15 years at least.”David McGough was one of the first British soldiers to arrive in Iraq. He was a lance corporal in the Royal Army Medical Corps at the age of 21.David told us, “We medics did exactly what the other soldiers did—patrols and stuff. The difference with us is we saw the after-effects of war as well. We saw the casualties. We had to deal with the carnage and death and destruction.” David would spend 17 hours a day dressing bodies that had been blown apart by shrapnel and ordnance, sewing the living dead back together, and watching others die. One incident in particular haunts him to this day. “There was a little girl about eight or nine. Her family had died. We were trying to do a nice thing by giving her water and bits of chocolate. One day we spotted a militia hanging her in an alleyway and we had to make the decision whether to go in and save her—which would have led to a riot and many more deaths—or just allow one person to die.” In the end, she was hanged.“When the militia left, we took her down and buried her. Most 21-year-olds are out getting drunk, but I’ve got that little girl on my conscience and I will until I die.”David was medically discharged after six months, with a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder a year later. Once he was back home, his weight plummeted, he couldn’t sleep, and he broke up with his girlfriend. He claims that his former colleagues were told not to speak to him. “I wouldn’t go out of the house. There was no contact and everything was failing around me and I felt like shit. The nightmares would make me go into the bathroom, lock the door, and cry for hours.”David has since attempted suicide twice—once with a knife and once with a gun that misfired.

uring his second tour of Iraq, in 2005, Mark Drydon was on a routine patrol. It was a Sunday. Fridays in Iraq are fairly quiet because everyone goes to mosques. Sunday, for Iraqis, is a fairly normal working day. But on this particular Sunday, it struck Mark that there was no one on the street.Mark told us, “It was like the Iraqi people knew what was going to happen. The road we drove up is usually one of the busiest ones in Basra but there were no kids, no cars, nothing. Suddenly there were two explosions. The first one was in the engine block, and the second came through my door. It all happened in seconds, but everything slowed down from the point of the second explosion going off. I knew I was badly injured. I was sent back to the medical-recovery station in a hotel nearby, where they can stabilize you and get you ready for the helicopter evacuation to the main hospital.“I don’t think that the British public have slagged the army off—they’ve slagged off the government for sending us. Now it’s like, why are we still out there? Why are we still getting killed and injured? I’d already done fighting in Iraq in 2003. I’ve been to Bosnia, Kosovo, and done two tours of Ireland, but I was more scared to go back to Iraq in 2005 than I ever was in my life. I even changed my life insurance and made sure my will was bang up-to-date before I went out there. When I look back to Northern Ireland in the 1970s, Iraq seems very similar. I think we will be there for another 10 or 15 years at least.”David McGough was one of the first British soldiers to arrive in Iraq. He was a lance corporal in the Royal Army Medical Corps at the age of 21.David told us, “We medics did exactly what the other soldiers did—patrols and stuff. The difference with us is we saw the after-effects of war as well. We saw the casualties. We had to deal with the carnage and death and destruction.” David would spend 17 hours a day dressing bodies that had been blown apart by shrapnel and ordnance, sewing the living dead back together, and watching others die. One incident in particular haunts him to this day. “There was a little girl about eight or nine. Her family had died. We were trying to do a nice thing by giving her water and bits of chocolate. One day we spotted a militia hanging her in an alleyway and we had to make the decision whether to go in and save her—which would have led to a riot and many more deaths—or just allow one person to die.” In the end, she was hanged.“When the militia left, we took her down and buried her. Most 21-year-olds are out getting drunk, but I’ve got that little girl on my conscience and I will until I die.”David was medically discharged after six months, with a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder a year later. Once he was back home, his weight plummeted, he couldn’t sleep, and he broke up with his girlfriend. He claims that his former colleagues were told not to speak to him. “I wouldn’t go out of the house. There was no contact and everything was failing around me and I felt like shit. The nightmares would make me go into the bathroom, lock the door, and cry for hours.”David has since attempted suicide twice—once with a knife and once with a gun that misfired.

ave Hart had been with the Territorial Army for years when the call came through that there would be opportunities to serve in Afghanistan. He had already done a tour in South Armagh and really enjoyed it. It reaffirmed why he had joined in the first place. He readily signed up for Afghanistan.Dave recalls, “The patrol that day was nothing out of the ordinary. There were four vehicles in line and I was in the first one, which was a stripped-down Land Rover. A suicide bomber had tried to get into Bagram US airbase, which was a few miles from us, but came to a vehicle checkpoint and decided to turn around. We had a couple of UN compounds down the road from us and he probably wanted to hit one of those, but he happened upon us instead. We were probably too much of a target to miss. I’ve been told that I was blown out of the vehicle. I don’t remember it. The driver was killed instantly. My mate Dave was in the passenger seat and lost his eye. I was on the ground, on fire. A couple of UN workers came over and doused me. My platoon sergeant flagged down a vehicle at gunpoint and threw us all in the back and got us to the multinational camp in seven minutes. I had already lost eight pints of blood. A couple more minutes and it would have been the end.“The next time I came round was in Germany. That diamorphine is pretty good stuff. I was off my tits for a while before I fell into a coma for about two and a half weeks. I was there for two months and was then flown back to the UK and taken to Selly Oak in Birmingham. It was a real comedown—really piss-poor to be honest. I went from intensive care in Germany with six nurses to Selly Oak, where you’re dumped in bed for three days, seen by a consultant, then cheers—off you go. And then I got MRSA, a lovely virus you can pick up in hospitals in the UK.”

ave Hart had been with the Territorial Army for years when the call came through that there would be opportunities to serve in Afghanistan. He had already done a tour in South Armagh and really enjoyed it. It reaffirmed why he had joined in the first place. He readily signed up for Afghanistan.Dave recalls, “The patrol that day was nothing out of the ordinary. There were four vehicles in line and I was in the first one, which was a stripped-down Land Rover. A suicide bomber had tried to get into Bagram US airbase, which was a few miles from us, but came to a vehicle checkpoint and decided to turn around. We had a couple of UN compounds down the road from us and he probably wanted to hit one of those, but he happened upon us instead. We were probably too much of a target to miss. I’ve been told that I was blown out of the vehicle. I don’t remember it. The driver was killed instantly. My mate Dave was in the passenger seat and lost his eye. I was on the ground, on fire. A couple of UN workers came over and doused me. My platoon sergeant flagged down a vehicle at gunpoint and threw us all in the back and got us to the multinational camp in seven minutes. I had already lost eight pints of blood. A couple more minutes and it would have been the end.“The next time I came round was in Germany. That diamorphine is pretty good stuff. I was off my tits for a while before I fell into a coma for about two and a half weeks. I was there for two months and was then flown back to the UK and taken to Selly Oak in Birmingham. It was a real comedown—really piss-poor to be honest. I went from intensive care in Germany with six nurses to Selly Oak, where you’re dumped in bed for three days, seen by a consultant, then cheers—off you go. And then I got MRSA, a lovely virus you can pick up in hospitals in the UK.”

rowing up in Bolton, Andy Barlow always fancied the military. As soon as he was done at school he joined up. He was 16. He completed relatively safe tours in Afghanistan and Iraq but then, on his second tour of Afghanistan, the shit hit the fan. Andy and his fellow soldiers walked right into a minefield.Andy told us: “One of our guys’ right legs had been blown off halfway down a mountain trail. The lads went down to give medical support and someone got on the radio asking for a chopper. Our corporal, whose name was Pearson, walked backward and set a mine off that took his leg as well. I began to tourniquet him when two other soldiers joined me—my friend Mark Wright and a medic I didn’t know. We waited for about an hour for a chopper to come and pull us out. When it finally came in to land, another mine was set off by a rock. That mine hit Mark badly. I was knocked back six feet with shrapnel injuries to my arm, and the medic had also been hit. I took a step toward Mark, and then another mine blew my foot clean off.“Mark passed away in the Chinook. He was next to me on the helicopter floor in a body bag. I knew that I was going to get my leg amputated—the fact that we had been waiting so long meant that gangrene had set in. I flew back to the UK, straight into Birmingham Airport, where they took me to Selly Oak Hospital. At the time Selly Oak were not prepared for as many casualties as it was getting. One of my main problems there was being on the same ward as civilians. Civvies are the last people you want to see after something like what happened to me.”

rowing up in Bolton, Andy Barlow always fancied the military. As soon as he was done at school he joined up. He was 16. He completed relatively safe tours in Afghanistan and Iraq but then, on his second tour of Afghanistan, the shit hit the fan. Andy and his fellow soldiers walked right into a minefield.Andy told us: “One of our guys’ right legs had been blown off halfway down a mountain trail. The lads went down to give medical support and someone got on the radio asking for a chopper. Our corporal, whose name was Pearson, walked backward and set a mine off that took his leg as well. I began to tourniquet him when two other soldiers joined me—my friend Mark Wright and a medic I didn’t know. We waited for about an hour for a chopper to come and pull us out. When it finally came in to land, another mine was set off by a rock. That mine hit Mark badly. I was knocked back six feet with shrapnel injuries to my arm, and the medic had also been hit. I took a step toward Mark, and then another mine blew my foot clean off.“Mark passed away in the Chinook. He was next to me on the helicopter floor in a body bag. I knew that I was going to get my leg amputated—the fact that we had been waiting so long meant that gangrene had set in. I flew back to the UK, straight into Birmingham Airport, where they took me to Selly Oak Hospital. At the time Selly Oak were not prepared for as many casualties as it was getting. One of my main problems there was being on the same ward as civilians. Civvies are the last people you want to see after something like what happened to me.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement