The image of the surface parking lot occupies permanent space in the subconscious of those raised in suburbia. Just imagine the expansive yards of pavement seemingly stretching out eternally and establishing, what James Howard Kunstler referred to as ‘The Geography of Nowhere.’ They’re simply giant black squares, the complete opposite of the natural landscape that now lies under them.Yet despite their overwhelming presence in our country, there is very little public discussion or analysis of parking lots' history, role, or future. City planner Eran Ben-Joseph sees a future for the urban space far from that of an ugly plot, and has written a fascinating book on the subject, ReThinking a Lot, out now from MIT Press. He took the time to chat with me about how America became swathed in blacktop, and what we can do to change that.I grew up in the suburbs, so I have always associated parking lots with the emergence of the strip mall aesthetic, the famous Joni Mitchell chorus, etc. How do these kinds of lots fit into the wider historical narrative of how parking lots in general?Four historical 'parking periods' follow the invention of the car. First, a shift from street curb parking to organized lots is observed. This reflects both the rapid increase in car ownership and the resulting problems associated with urban congestion. The shift also echoes the early 20th century’s enthrallment with rationality, order, and the scientific application of rules and codes to urban planning.By the mid-20th century, lot design corresponds to changes in urban dynamics, particularly growth of the suburbs and decline of city centers. The third period, around the last quarter of the 20th century, is characterized by the utilitarian planning and design of parking lots. Universal application of parking lot designs that disregard local conditions and discourage innovative design becomes the norm. Then the first decade of the 21st century is exemplified with a greater awareness of the environmental impacts of parking lots and further incorporation of mitigation strategies.In the 1920s, cities across America started to allocate space for parking lots that were either owned and managed privately by commercial and retail associations or owned by public entities and maintained by private operators. Some of these lots were within downtown areas and others located at city perimeters. One of the earliest municipal lots was constructed in Los Angeles in 1922, followed by Flint, MI in 1924, and Chicago and Boston in 1930.The shift towards building parking lots echoes the early 20th century’s enthrallment with rationality, order, and the scientific application of rules and codes to urban planning.

—It is no surprise that some of the earliest surface parking lots in the United States were designed and built next to shopping centers. In 1923, the J. C. Nichols Company constructed two lots of 150-car capacity next to the new Country Club Plaza Shopping Center in Kansas City, Missouri. According to Davis K. Jackson, the engineer who worked on its creation, "This was a radical departure from the normal practice at that time, but it has since become widely accepted, and large free parking areas are generally considered essential for any suburban development."1Although Jackson advocated ample free parking, his actual design was sensitive to the overall site conditions. He believed in smaller, 'well-located' lots, and emphasized that "it is important that parking lots not be too large." "Otherwise", he said, "there is a risk of serious interruption to the retail continuity of the shops." He describes the lot designs as "beautified… with masonry walls, vines, flowers, trees, shrubs, and objects of art." He endorsed the belief that such expense is justified as part of creating an attractive shopping experience.2By the mid-20th century, lot design corresponded to changes in urban dynamics, particularly the growth of the suburb and the decline of the city core. The booming growth of suburban development and its associated auto-centric culture, spurred the decline of Central Business Districts (CBD) in many cities. This dynamic promoted construction of surface lots on the lots of torn down vacant buildings, in hopes of attracting suburbanites back into the city centers with "easy parking."What are some of the environmental considerations that the prevalence of parking lots generate?Most parking lots are paved with watertight concrete and asphalt supported with water removal infrastructure. This engineered piping system is built in to remove water as fast as possible from the site to the nearest stream by a system of curbs, gutters and pipes. Yet the consequence of efficiently and speedily removing rainwater has also caused downstream flooding, erosion, and loss of valuable property and land. A one-acre parking lot produces almost 16 times the volume of runoff than that from a similarly sized meadow; it not only increases water volume runoff but also prevents recharge of the aquifer. As runoff flows across paved parking lots, water temperature rises and pollutants such as oil, metals and soils are carried into streams and waterways. Consequently, decreases in oxygen levels and increases in nitrogen threaten the thresholds needed to keep a healthy habitat.Atlanta's water "losses"amount to enough water to supply the average daily household needs of 1.5 million to 3.6 million people per year.

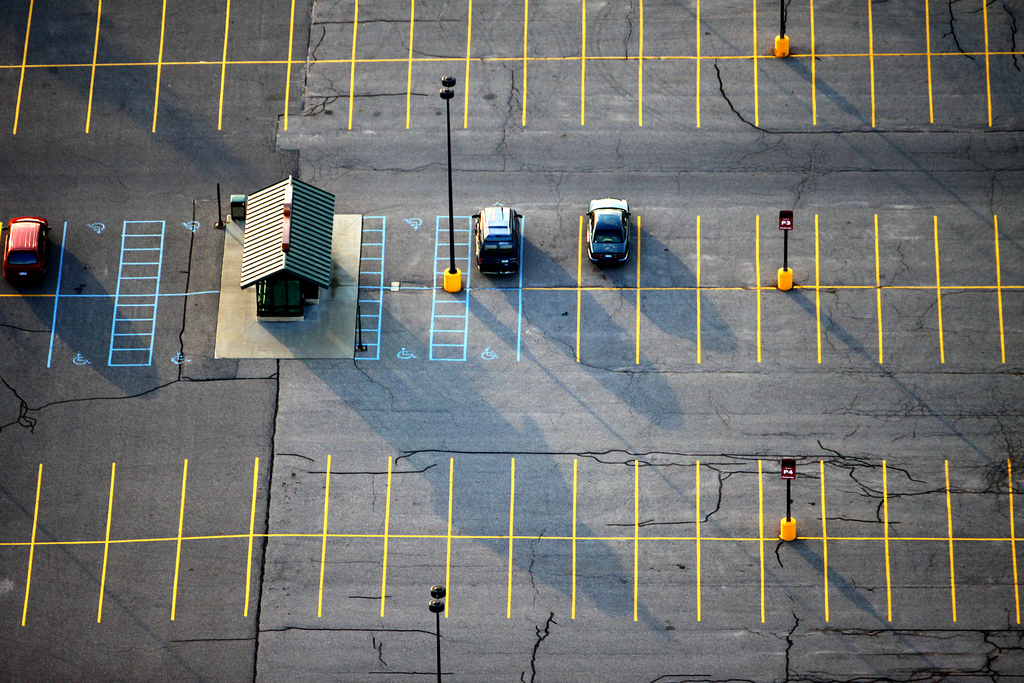

—Excessive impervious surfaces and piped drainage systems associated with parking lot design also pose danger to the supply of potable water. A joint study by the American Rivers, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and Smart Growth America showed that in some of the largest metropolitan areas, the potential amount of water not infiltrated annually ranges from 14.4 billion gallons in Dallas to 132.8 billion gallons in Atlanta. Atlanta's "losses" for example, amount to enough water to supply the average daily household needs of 1.5 million to 3.6 million people per year.3With the replacement of natural vegetated surfaces with parking lots composed of asphalt and concrete, overall city temperatures are on the rise. The temperatures of these artificial surfaces can be 68 to 104°F (20 to 40°C) higher than vegetated surfaces. Asphalt pavement, in particular, accumulates excessive heat because of its dark color and low moisture content. Pavement acts as a "thermal battery," heat collects during the day and is released slowly overnight. This produces a dome of elevated warmer air temperatures (“urban heat island”) over the city, compared to the air temperatures over adjacent rural areas.A remote sensing experiment that scanned temperatures of Huntsville, Alabama by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) showed that heating of road and parking lot surfaces, especially those using asphalt, contributed most to warming patterns. In specific measurements of a mall and its surrounding parking lot, an average temperature of 113°F (45°C) was recorded compared with a nearby forested area at 85°F (29.6°C). In a spot check of day temperatures in the middle of the parking lot, temperatures reached about 120°F (48.8°C) . However, a small tree island planter containing a couple of trees in the parking lot reduced the temperature by almost 30°F (17.2°C).4Environmental impacts of parking are not limited to water, heat, increases of impervious surfaces or decreases in natural habitat. Parking also has bearing on the energy and emission contributions from vehicles. Research also shows that parking spaces raise the amount of carbon dioxide emitted per mile by as much as 10 percent for an average car and the amount of other gases such as sulfur by as much as 25 percent and the amount of soot by as much as 90 percent.5How do you see parking lots changing as our relationships with automobiles shift and change? Are we already starting to see a change in how much they are needed?My view on the subject may go against the grain of many who may indeed be longing for a future where we 'tear down a parking lot and put up paradise.’ The reality is that parking and parking lots are here to stay. As long as our preferred form of mobility remains with personal transportation modes, the car (whether powered by fossil fuel, solar, or hydrogen) will continue to dominate our environment, cultural and social life. The question of where we park it and how we design spaces for it remain as essential as questions about the type of cars we will use in the future.When starting with such a base concept, there’s lots of room for improvement. Photo by Jeffrey Smith, via The City Fix.

With the prevailing ambivalence toward cars, and the refusal to view them as possible design elements, cars and parking lots are dealt with as a necessary evil.

—Parking lots provide a blank canvas that can accommodate many changes and uses within the built environment. We must not forget this aspect of these unique spaces or all parking lots will look and function alike and be deprived of their potential ability to be spontaneously changed. Public officials, developers and operators of parking lots should realize that mixing uses in parking lots could be profitable. For example, allowing food trucks into a parking lot to create 'lunch in the square' generates revenue to those vendors, the city through permitting fees, and other local businesses (non-competing) through increased foot traffic caused by the event.Developers can also realize that parking lots are just as important to their development image and attractiveness as are glamorous lobbies or fancy facades. Developers of condominiums do not shy away from adding exercise and recreation facilities to lure people into buying a unit. Most understand that investment in common spaces can have positive economic outcomes. The developer, as one of the sole deciders of how a city is ultimately shaped, needs to believe that improving the parking facilities can be beneficial to both buyers and lessees of their buildings as well as to the long-term viability of the surrounding area.The options are limitless. It is time to shift from the modest and lackluster attitudes about parking lots toward attitudes that celebrate and acknowledge the great potential of these spaces.

Footnotes

1 Jackson, Davis. January 1951. "Parking Needs in the Development of Shopping Centers," Traffic Quarterly. 32-37. 322 Ibid. 33-343 American Rivers, Natural Resources Defense Council, and Smart Growth America. 2002. Paving Our Way to Water Shortages: How Sprawl Aggravates the Effects of Drought. Smart Growth America, Washington, D.C.4 Luvall, Jeffrey and Dale Quattrochi. 1996. "What’s Hot in Huntsville and What’s Not: A NASA Thermal Remote Sensing Project," NASA’s Global Hydrology and Climate Center5 Betz, Eric. Dec 1, 2010. " No Such Thing As Free Parking," ISNS. Retrieved Feb. 6, 2011. http://www.insidescience.org/research/no-such-thing-as-free-parking.

For original study see: Chester, Mikhail, Arpad Horvath and Samer Madanat. 2010.Connections: