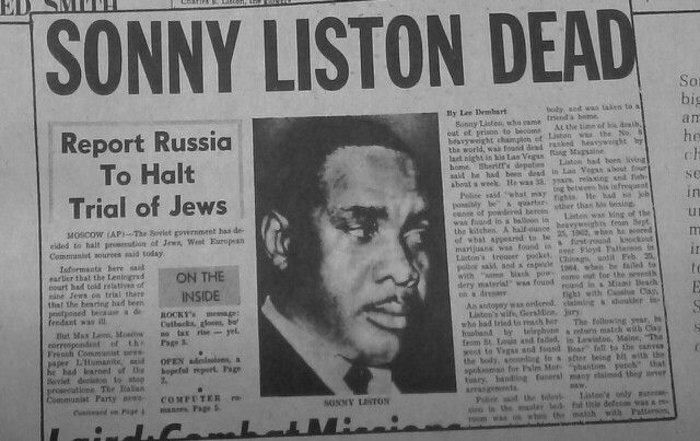

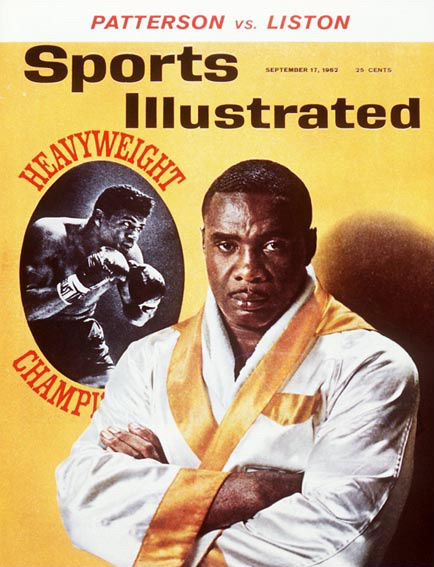

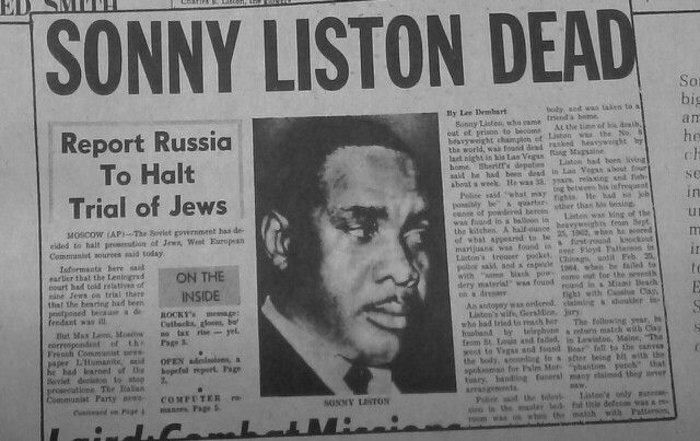

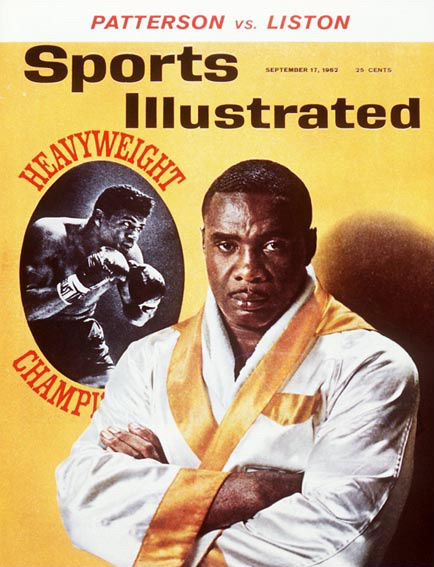

Was Sonny Liston the victim of foul play? That's the premise of The Murder of Sonny Liston: Las Vegas, Heroin, and Heavyweights, a cracking new book by Shaun Assael that looks at the twilight years of the controversial and formidable heavyweight boxing champ.Liston's death from a heroin overdose on January 5th, 1971, has long been seen as accidental, but Assael, a two-fisted journalist for ESPN, puts forward the murder theory and identifies four underworld figures with a strong motive for whacking the ex champ.For those of you who don't know, Charles "Sonny" Liston was the Mike Tyson of the 1960s, a winner America did not much like. Liston went from being a big-shouldered street thief with no education to heavyweight champ of the world and household name. Born in Forrest City, Arkansas, sometime in the late 1920s and early 1930s (his exact date of birth is unknown), Liston was the 24th of 25 children born to a sharecropper father. As a teenage delinquent in St. Louis, he got a 5-year sentence for robbing gas stations and restaurants. Banged up in Missouri State Penitentiary, Liston learned to box and became the prison champion. After serving 2 years, Liston was paroled to a team of mob connected boxing handlers and began his pro-career shortly after. His first bout, against Don Smith, lasted 33 seconds.Then, as now, no one is ever truly rehabilitated from a prison sentence in America. When the intimidating, hard-jabbing Liston was touted as a challenger to the fast-handed-but-chinless heavyweight champ Floyd Patterson in 1960, Congress debated whether a man with an arrest record and negative image like Liston's should fight for the most glorious sporting title in the world. They cited the instance when Liston broke the leg of a racist cop in 1956 and dumped another headfirst into a trashcan. The fearsome puncher defended himself in a testimony before a Senate committee. He bluntly told the gallery of white faced men that he couldn't read, couldn't write and had worked as a child to help support his parents and 24 siblings. Moreover, he did not play down his connections to mob figures. This was boxing. And the politicians up on the hill knew that it came with the territory. An ex con. A thug. A big assed black guy who liked to get drunk and fight police officers! Sonny Liston was demonized as the white man's nightmare. Though he had overcome enormous odds in his life, no one in America wanted him to be a winner. He was the undesirable who had the mob in his corner. When he eventually got his shot against Floyd Patterson in 1962, the then President of the U.S.A., John. F. Kennedy reached out to the incumbent champ and invited him to the White House. Kennedy urged victory and cautioned Patterson about the negative image a Liston win might generate to African-American youth. As far as Kennedy was concerned, Floyd Patterson vs. Sonny Liston was "Good Negro" vs. "Bad Negro."The only public figure who came out in sympathy for Sonny Liston was the author and essayist James Baldwin. Black and homosexual, Baldwin knew about being disenfranchised from the mainstream of American life, and was able to identify with the alienation of Sonny Liston. Baldwin peered through the thuggish stereotype—largely media made—and saw in Liston, the hulking body snatcher, a troubled, complex and contradictory figure. "The press has really maligned Liston very cruelly, I think. He is far from stupid; is not, in fact, stupid at all. On the contrary, he reminded me of big, black men I have known who acquired the reputation of being tough in order to conceal the fact that they weren't hard." Sympathy or not, it didn't stop Baldwin rooting for Patterson to win.Liston brutally mugged Patterson in Chicago for the first heavyweight title fight ever decided in the opening round. When Liston flew back home to Philadelphia, there was no heroes' welcome, no open topped car, tickertape parade or freedom of the city. That crushed the newly minted champ. In private, Liston was known as generous and a fun loving charmer. Now he was cast as the neighborhood bully and had to make do with the role. It was another bum rap for Sonny Liston.Liston lost the belt in 1964 and faced Clay again in a chaotic 1965 rematch when he had changed his name to Muhammad Ali. Liston was felled by a "phantom punch" in the second round. A lot of observers and commentators at ringside didn't see the right-hand "anchor punch" that snapped Liston's neck, and the sports press cried fix. According to Assael's book, there were many rumors that Resnick, on the behalf of Liston, made a deal with the Nation of Islam to take a dive in exchange for a percentage of Ali's future earnings in the ring. This has never been proven, nor less substantiated.Under the corrupting influence of Resnick, Liston moved to Las Vegas and started to try and get his boxing back on track. From 1966 to 1969 he enjoyed 15 straight wins against journeymen opponents and even had the then Olympic champ George Foreman in camp as a sparring partner. Liston did adverts on TV and even landed small roles in films and TV shows, but his fight career went south after a crushing knock out by Leotis Martin, a former sparring partner, in 1969.The ex felon had skills to fall back on. Whilst his boxing career was drawing to its close, a hard up Liston had been working as a henchman/enforcer for Robert Chudnick, a kleptomaniac jazz musician turned drug dealer. Together with Chudnick's teenage son, Mark, Liston was one half of a "collections team." Everything was going dandy until one night in Las Vegas in February 1969. Liston was partying at the home of a drug dealer named Earl Cage when cops from the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD), the forerunner of the Drug Enforcement Agency, busted it. Everyone at the party got arrested—except for Liston. Robert Chudnick began to suspect that Liston was a snitch and cautioned his son to stop working with him. This enmity was cemented in 1970 when Liston bitch slapped Mark Chudnick in a row over drug money.The checkered boxer fought his last bout against Chuck Wepner in June of 1970. "He was the hardest puncher that I ever fought," said Wepner, "It was like getting hit with a baseball bat." Wepner needed 72 stitches that night and Liston got $13,000 for the bout. He saw none of it. His purse was used to settle a gambling debt. Nevertheless, the 6-foot plus, 215-pound fighting machine had made his mark and retired with a 50-4 fight record and 39 knockouts.On January 5, 1971, Liston's wife, Geraldine, found the ex champ's dead body. Drug paraphernalia surrounded his decomposing, bloated corpse and he had been dead for several days. The autopsy at the time was inconclusive. Heroin may have been a factor, but was it self-administered? The coroner said that Liston had died of natural causes and the police closed the book on the investigation.

An ex con. A thug. A big assed black guy who liked to get drunk and fight police officers! Sonny Liston was demonized as the white man's nightmare. Though he had overcome enormous odds in his life, no one in America wanted him to be a winner. He was the undesirable who had the mob in his corner. When he eventually got his shot against Floyd Patterson in 1962, the then President of the U.S.A., John. F. Kennedy reached out to the incumbent champ and invited him to the White House. Kennedy urged victory and cautioned Patterson about the negative image a Liston win might generate to African-American youth. As far as Kennedy was concerned, Floyd Patterson vs. Sonny Liston was "Good Negro" vs. "Bad Negro."The only public figure who came out in sympathy for Sonny Liston was the author and essayist James Baldwin. Black and homosexual, Baldwin knew about being disenfranchised from the mainstream of American life, and was able to identify with the alienation of Sonny Liston. Baldwin peered through the thuggish stereotype—largely media made—and saw in Liston, the hulking body snatcher, a troubled, complex and contradictory figure. "The press has really maligned Liston very cruelly, I think. He is far from stupid; is not, in fact, stupid at all. On the contrary, he reminded me of big, black men I have known who acquired the reputation of being tough in order to conceal the fact that they weren't hard." Sympathy or not, it didn't stop Baldwin rooting for Patterson to win.Liston brutally mugged Patterson in Chicago for the first heavyweight title fight ever decided in the opening round. When Liston flew back home to Philadelphia, there was no heroes' welcome, no open topped car, tickertape parade or freedom of the city. That crushed the newly minted champ. In private, Liston was known as generous and a fun loving charmer. Now he was cast as the neighborhood bully and had to make do with the role. It was another bum rap for Sonny Liston.Liston lost the belt in 1964 and faced Clay again in a chaotic 1965 rematch when he had changed his name to Muhammad Ali. Liston was felled by a "phantom punch" in the second round. A lot of observers and commentators at ringside didn't see the right-hand "anchor punch" that snapped Liston's neck, and the sports press cried fix. According to Assael's book, there were many rumors that Resnick, on the behalf of Liston, made a deal with the Nation of Islam to take a dive in exchange for a percentage of Ali's future earnings in the ring. This has never been proven, nor less substantiated.Under the corrupting influence of Resnick, Liston moved to Las Vegas and started to try and get his boxing back on track. From 1966 to 1969 he enjoyed 15 straight wins against journeymen opponents and even had the then Olympic champ George Foreman in camp as a sparring partner. Liston did adverts on TV and even landed small roles in films and TV shows, but his fight career went south after a crushing knock out by Leotis Martin, a former sparring partner, in 1969.The ex felon had skills to fall back on. Whilst his boxing career was drawing to its close, a hard up Liston had been working as a henchman/enforcer for Robert Chudnick, a kleptomaniac jazz musician turned drug dealer. Together with Chudnick's teenage son, Mark, Liston was one half of a "collections team." Everything was going dandy until one night in Las Vegas in February 1969. Liston was partying at the home of a drug dealer named Earl Cage when cops from the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD), the forerunner of the Drug Enforcement Agency, busted it. Everyone at the party got arrested—except for Liston. Robert Chudnick began to suspect that Liston was a snitch and cautioned his son to stop working with him. This enmity was cemented in 1970 when Liston bitch slapped Mark Chudnick in a row over drug money.The checkered boxer fought his last bout against Chuck Wepner in June of 1970. "He was the hardest puncher that I ever fought," said Wepner, "It was like getting hit with a baseball bat." Wepner needed 72 stitches that night and Liston got $13,000 for the bout. He saw none of it. His purse was used to settle a gambling debt. Nevertheless, the 6-foot plus, 215-pound fighting machine had made his mark and retired with a 50-4 fight record and 39 knockouts.On January 5, 1971, Liston's wife, Geraldine, found the ex champ's dead body. Drug paraphernalia surrounded his decomposing, bloated corpse and he had been dead for several days. The autopsy at the time was inconclusive. Heroin may have been a factor, but was it self-administered? The coroner said that Liston had died of natural causes and the police closed the book on the investigation. Fast forward to 1982, a police informant named Irwin Peters alleged that Larry Gandy, a former Las Vegas cop, had killed Liston. Liston had had an argument with Ash Resnick over money and Gandy was hired to kill Liston with a "hot shot" of heroin. Dirty cop Gandy, a part time burglar, was later arrested and sentenced to 10 years in prison but the authorities could find no evidence for murdering Liston. As for Irwin Peters the snitch, he received anonymous threats via postcard and was found dead in his garage in 1987 with the car still running. The death was put down to a leaky exhaust but family members told Shaun Assael that they believe it was suspicious.Assael contacted Larry Gandy on Facebook in 2014 for an interview. Upon meeting, and totally unprompted, the ex cop said to him, "So, you've come to ask me if I killed Sonny Liston?" Gandy denied it and told Assael that he believed Earl Cage killed Liston. Cage passed away in 2000 but Gandy put the motive down to the 1969 drug raid when everyone got nabbed but Liston. One officer from the bust, former BNDD agent Bill Alden, believes as much, "Knowing Las Vegas like I did, and knowing Sonny's history, I always felt he was murdered. There was just too much there."Gandy. Resnick. Cage. Chudnick. Assael's four suspects all had possible motives for taking out Liston. At the end of the book, he reaches the conclusion that if you were to solve the death of informant Irwin Peters, you would also be able to solve the mysterious and untimely death of Charles "Sonny" Liston. It's a mystery for another book to figure out.

Fast forward to 1982, a police informant named Irwin Peters alleged that Larry Gandy, a former Las Vegas cop, had killed Liston. Liston had had an argument with Ash Resnick over money and Gandy was hired to kill Liston with a "hot shot" of heroin. Dirty cop Gandy, a part time burglar, was later arrested and sentenced to 10 years in prison but the authorities could find no evidence for murdering Liston. As for Irwin Peters the snitch, he received anonymous threats via postcard and was found dead in his garage in 1987 with the car still running. The death was put down to a leaky exhaust but family members told Shaun Assael that they believe it was suspicious.Assael contacted Larry Gandy on Facebook in 2014 for an interview. Upon meeting, and totally unprompted, the ex cop said to him, "So, you've come to ask me if I killed Sonny Liston?" Gandy denied it and told Assael that he believed Earl Cage killed Liston. Cage passed away in 2000 but Gandy put the motive down to the 1969 drug raid when everyone got nabbed but Liston. One officer from the bust, former BNDD agent Bill Alden, believes as much, "Knowing Las Vegas like I did, and knowing Sonny's history, I always felt he was murdered. There was just too much there."Gandy. Resnick. Cage. Chudnick. Assael's four suspects all had possible motives for taking out Liston. At the end of the book, he reaches the conclusion that if you were to solve the death of informant Irwin Peters, you would also be able to solve the mysterious and untimely death of Charles "Sonny" Liston. It's a mystery for another book to figure out.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

One year later, in a rematch, Patterson got knocked out once again by Liston in the first round. It was during training for that bout in Las Vegas in 1963 that Liston met a shady New York mob figure who would later loom large as a suspect in his death: a fight promoter and casino operator named Ash Resnick. In a very short space of time, Resnick wormed his way into Liston's entourage and became the champ's gofer and confidant.Nemesis came in the form of a fresh punk with a big mouth. A pumped up light heavyweight, no less! Everyone thought that Liston would hospitalize Cassius Clay. Moreover, it was a very confusing time for the general public. Nobody liked Liston the sullen champ, and not many people liked Clay the insolent young challenger. Most of the bookies thought Liston would pulverize Clay (he was an 8/1 favorite), and of the 46 journalists covering the fight, only 3 picked Clay to win. Political figures weighed into the debate, too. Malcolm X went on the record to publicly root for Clay.

Advertisement

Advertisement