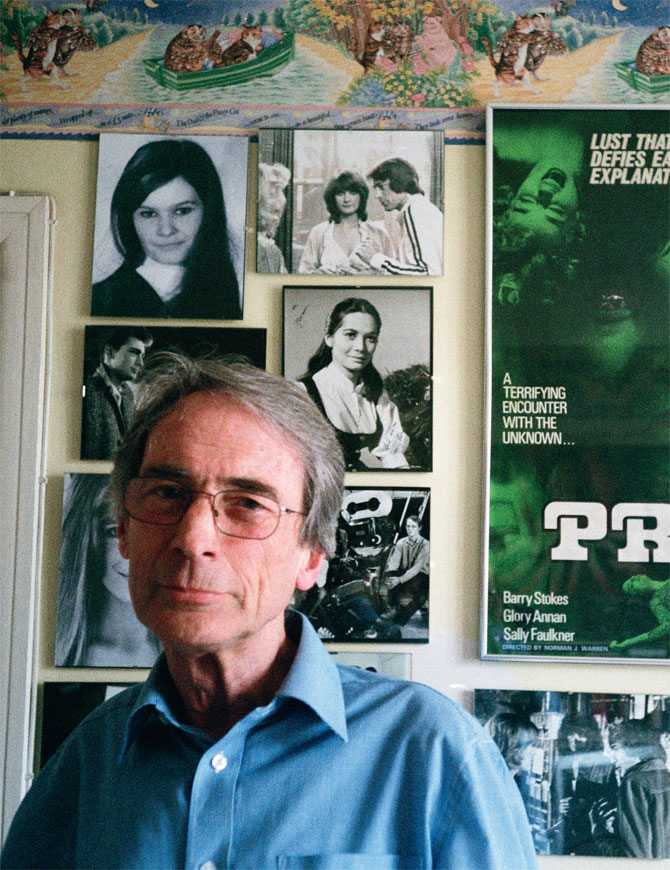

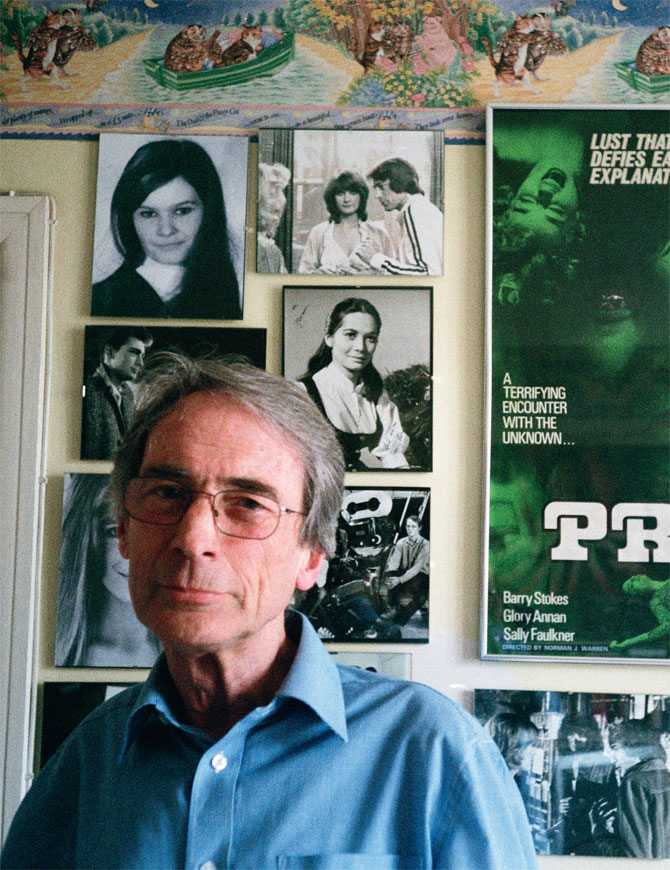

Words and Photo By Bruno BayleyStills and Artwork Courtesy of Norman J. Warren Until the middle of the 1970s, British horror films tended to be camp, period rehashes of American horror classics in which hammy, top hat-wearing toffs would end up being killed by the big guys from the gore of yore such as Dracula and werewolves. Not surprisingly, that wasn’t enough to keep the youth of 70s Britain on the edge of their seats, let alone in the cinemas. Then, directors realised that if these thrillers were set in the suburbs and featured run-of-the mill characters called Derek and Lorraine, who didn’t speak like elocution coaches, people might care again.Norman J. Warren was one of the first directors in Britain to have this epiphany. He made groundbreaking cult filmsSatan’s Slave, Prey,andTerrorin the 70s and got away with exposing Britain to unprecedented levels of gore and sex with minimal opposition. This was before the UK’s censors went crazy over American horror films likeDriller Killer, and clamped down on so-called “video nasties”.Vicespent a few hours with Mr. Warren, who is nearly 70, in his west London home. His office is crammed with stacks of stills, posters, photographs and soundtracks, as well as countless bits of merchandise and old cameras. While a plastic alien loomed over us, we talked about the problems one encounters when attempting to show blood smeared on naked breasts. It was great.Vice: When you started making films, the British horror genre was broadly in the “Hammer Horror” tradition, wasn’t it?Norman J. Warren:There was horror stuff being made in Britain back in the 20s and early 30s, but then it fell out of favour with the cinema. They moved toward a “family films only” policy. Hammer were a small company making thrillers and war films. Someone suggested that they had a go at the old horror classics, and they didFrankensteinand it was a massive success. It was incredible. That huge success made British cinemas change their policy as soon as they realised that money was to be made. It was Hammer that actually opened up the door for horror in this country.But they were a pretty direct translation of the American predecessors?Oh yeah, but they did it very well. It was all very gothic and period. But it got tiring for people like me and other young fans. Hammer finally died because they failed to keep up. It was so easy for them that they just carried on making these films without thinking. They got stuck in a rut. The problem was, it was always period settings about middle-class people with a great deal of money, and it was incredibly hard for young audiences to relate to.

Until the middle of the 1970s, British horror films tended to be camp, period rehashes of American horror classics in which hammy, top hat-wearing toffs would end up being killed by the big guys from the gore of yore such as Dracula and werewolves. Not surprisingly, that wasn’t enough to keep the youth of 70s Britain on the edge of their seats, let alone in the cinemas. Then, directors realised that if these thrillers were set in the suburbs and featured run-of-the mill characters called Derek and Lorraine, who didn’t speak like elocution coaches, people might care again.Norman J. Warren was one of the first directors in Britain to have this epiphany. He made groundbreaking cult filmsSatan’s Slave, Prey,andTerrorin the 70s and got away with exposing Britain to unprecedented levels of gore and sex with minimal opposition. This was before the UK’s censors went crazy over American horror films likeDriller Killer, and clamped down on so-called “video nasties”.Vicespent a few hours with Mr. Warren, who is nearly 70, in his west London home. His office is crammed with stacks of stills, posters, photographs and soundtracks, as well as countless bits of merchandise and old cameras. While a plastic alien loomed over us, we talked about the problems one encounters when attempting to show blood smeared on naked breasts. It was great.Vice: When you started making films, the British horror genre was broadly in the “Hammer Horror” tradition, wasn’t it?Norman J. Warren:There was horror stuff being made in Britain back in the 20s and early 30s, but then it fell out of favour with the cinema. They moved toward a “family films only” policy. Hammer were a small company making thrillers and war films. Someone suggested that they had a go at the old horror classics, and they didFrankensteinand it was a massive success. It was incredible. That huge success made British cinemas change their policy as soon as they realised that money was to be made. It was Hammer that actually opened up the door for horror in this country.But they were a pretty direct translation of the American predecessors?Oh yeah, but they did it very well. It was all very gothic and period. But it got tiring for people like me and other young fans. Hammer finally died because they failed to keep up. It was so easy for them that they just carried on making these films without thinking. They got stuck in a rut. The problem was, it was always period settings about middle-class people with a great deal of money, and it was incredibly hard for young audiences to relate to.

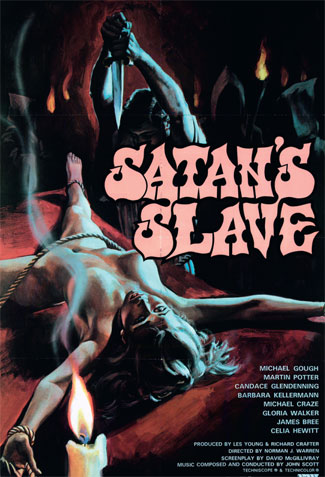

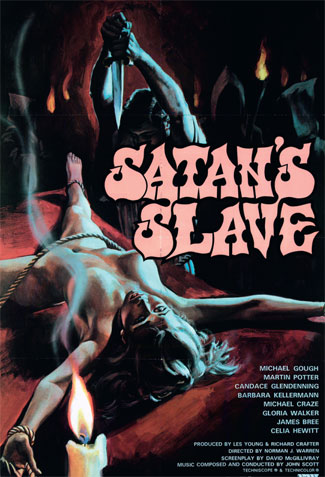

Terror (1979) Click to enlargeInseminoid (1981)And you were a Hammer fan?I made an effort to move away from that stilted Hammer way of doing things, but we were still influenced by them. You can see it inSatan’s Slave. But we started transferring the stories to modern-day settings, and used the language of the time. Of course we upped the gore level, and the nudity too. We wanted to break away from Hammer—but there were no other influences to draw on. And when you are making your first film, especially when you have put your own money into it, you tend to want to play it safe. Making horror was a commercial move; I guess we stuck with the Hammer basis because we needed it to be picked up by distributors. It had to still be within their frames of reference.In bringing horror up to date, did you ever try to inject any social commentary or was your main aim to avoid the period trappings of Hammer?Not really. I mean, the films were obviously very much of their time. I mean, people might say, “It’s a real 70s movie”, but needless to say no one in the 70s wanted to make a 70s film—it was just a film. I never really had any interest in making films with social comment, I just wanted to make entertainment. We just wanted to be sure it wasn’t period. Though, as it happened, for the first film,Satan’s Slave, we found an amazing old house that just happened to actually be very Hammer in style, with drapes and antiques and so on, but that was just chance.As far as making the most entertaining film possible goes, how did that affect the plot or writing process?There were films where I pretty much worked out what scenes and events I wanted to see and worked out a story to fit them, butSatan’s Slavewas more conventional, plot-wise. It holds up alright today, even though I find it a bit slow. But the main problem with it was that the plot was very complicated, and actually rather boring. So we just cut out complete scenes where people were explaining things. And a lot of the film doesn’t make sense because of those cuts. But it was less complicated, and no one ever questioned the plot. Two years later we had luckily made enough money from it to make another film. By then things had changed. We had the money. The question was, what to make?So is this when you changed your writing technique?Both myself and the producer had quite independently seen a film calledSuspiria, made by Dario Argento. It had gone against all the rules: there was no real plot, it didn’t really make sense, but it had wild colours and great sound effects. It reaffirmed the idea that entertainment was the priority over detail and logic. We made a list of things we liked in other films, like girls breaking down illuminated by lightning, or cottages in the middle of nowhere that are unlocked even though no one is in.We asked David McGillivray if he could make a storyline out of the bits and string them all together. He did, and it sort of made sense, but if you look at it closely then you can’t really analyse it. WithSatan’s Slave, we had been overly worried about the audience understanding it, but actually it turned out we didn’t need to be, because they didn’t care.

Terror (1979) Click to enlargeInseminoid (1981)And you were a Hammer fan?I made an effort to move away from that stilted Hammer way of doing things, but we were still influenced by them. You can see it inSatan’s Slave. But we started transferring the stories to modern-day settings, and used the language of the time. Of course we upped the gore level, and the nudity too. We wanted to break away from Hammer—but there were no other influences to draw on. And when you are making your first film, especially when you have put your own money into it, you tend to want to play it safe. Making horror was a commercial move; I guess we stuck with the Hammer basis because we needed it to be picked up by distributors. It had to still be within their frames of reference.In bringing horror up to date, did you ever try to inject any social commentary or was your main aim to avoid the period trappings of Hammer?Not really. I mean, the films were obviously very much of their time. I mean, people might say, “It’s a real 70s movie”, but needless to say no one in the 70s wanted to make a 70s film—it was just a film. I never really had any interest in making films with social comment, I just wanted to make entertainment. We just wanted to be sure it wasn’t period. Though, as it happened, for the first film,Satan’s Slave, we found an amazing old house that just happened to actually be very Hammer in style, with drapes and antiques and so on, but that was just chance.As far as making the most entertaining film possible goes, how did that affect the plot or writing process?There were films where I pretty much worked out what scenes and events I wanted to see and worked out a story to fit them, butSatan’s Slavewas more conventional, plot-wise. It holds up alright today, even though I find it a bit slow. But the main problem with it was that the plot was very complicated, and actually rather boring. So we just cut out complete scenes where people were explaining things. And a lot of the film doesn’t make sense because of those cuts. But it was less complicated, and no one ever questioned the plot. Two years later we had luckily made enough money from it to make another film. By then things had changed. We had the money. The question was, what to make?So is this when you changed your writing technique?Both myself and the producer had quite independently seen a film calledSuspiria, made by Dario Argento. It had gone against all the rules: there was no real plot, it didn’t really make sense, but it had wild colours and great sound effects. It reaffirmed the idea that entertainment was the priority over detail and logic. We made a list of things we liked in other films, like girls breaking down illuminated by lightning, or cottages in the middle of nowhere that are unlocked even though no one is in.We asked David McGillivray if he could make a storyline out of the bits and string them all together. He did, and it sort of made sense, but if you look at it closely then you can’t really analyse it. WithSatan’s Slave, we had been overly worried about the audience understanding it, but actually it turned out we didn’t need to be, because they didn’t care. Click to enlargeThe whole video nasty thing came along after you started making films, but still I can’t believe that you had no trouble making films like these in the mid-70s for a British audience.I think we just hit at the right time.Terrorwas breaking box office records in America—they kept it on for weeks. They had never made so much money. It wasn’t shocking to the audience it was aimed at.What was your view about the whole video nasty hysteria, as someone who had been making fairly groundbreaking horror films years before without complaint?Well, the video nasties thing was all fairly random. I think they often didn’t look at the films at all. They just picked films with titles that sounded bad and tried to ban them. I rememberDriller Killer—it was alright, it was just a bit silly, really. I was quite happy some of them were banned because they were just rather silly.Nightmare in a Damaged Brainwas the main one people were upset about—it should have been banned for being a terrible film, but it is so ludicrous that I don’t think it could have affected anyone negatively.I Spit on Your Grave, however, caused uproar because of the sexual nature of it—rape is very dicey, always has been, for obvious reasons.But your films were heavily sexual. The first films you directed were sex films, weren’t they?Yes. They were softcore, if you saw them now they would seem silly. The first was calledHer Private Hell.I had been working as an editor on documentaries and commercials, and obviously I was always trying to get someone to finance a film for me to direct. I was so frustrated that I decided to make a short film. It was running at a cinema in South Kensington and a friend of the owner was a distributor who wanted to go into business making low-budget films, something a bit more commercial. They needed a director for a sex film, and they were in the cinema as my film was showing, so I got a phone call.Her Private Hellis not great. It stands up OK today. But back then the film was an amazing success. It was the first British sex film that told a story. Before that it had been people playing tennis at a nudist camp. But this was a 90-minute drama about a girl being exploited in the fashion business, along with lots of people taking their clothes off. There was one cinema where it ran for 24 months doing ten shows a day. The second sex film,Loving Feeling, was also successful, but not as much so. Other sex films were starting to compete. Still, it did fine. They asked me to do a third, but I said no. Working with naked ladies gets very boring from a director’s point of view—it’s just people taking clothes off and getting into bed.Did you ever have to hold yourself back from certain levels of violence, sex or gore?Not really. We were never doing anything we thought would offend anyone, we weren’t setting out to cause offence. Strangely enough,Terrordidn’t get many complaints. The censor had one main problem with it: there is a scene where a girl gets stabbed, ormanystabs, I should say, on a staircase. There were a couple of shots where the knife went through her feet, and they had to be cut. They didn’t mind a knife going through her body. I can only think whoever was examining at the time had a real problem with feet in general.Censor-wise, surely religion caused problems? Satan’s Slave must have been tough?Satan’s Slavedid get more cuts. It was 1975, and it was tricky. But at the time we were always making alternative cuts and scenes for other countries. There was a scene where a girl was whipped, naked, against a tree. They were not fond of that here, and in the end it was almost non-existent in the UK version of the film. Another scene that sticks in the mind was one where we had a girl lying on an altar with blood smeared on her body. That was fine, but we had to avoid getting any blood on her breasts. According to the censors, blood on the breast would make men likely to commit rape!We made one scene inSatan’s Slaveexclusively for the far east market. It was a very gratuitous bedroom scene. I was never fond of it, it wasn’t horror, it was just intimidating and nasty. The girl was tied, spread-eagled, to the bed and threatened. There was no blood, but it was very brutal. She is semi-suffocated, then her clothing is cut off with scissors before the man, played by Martin Potter, threatens to cut off her nipples. It was horrible.Was Satan’s Slave your main battle with the censors?There was a lot of fuss aboutInseminoid. In fact, it was mainly successful because lots of women’s groups tried to ban it. There was a part in the film where a woman is inseminated by an alien and gives birth to a monster, but apparently giving birth to a monster is a very common nightmare for pregnant women. We didn’t know that. They said we were exploiting women and their fears. It was great publicity.

Click to enlargeThe whole video nasty thing came along after you started making films, but still I can’t believe that you had no trouble making films like these in the mid-70s for a British audience.I think we just hit at the right time.Terrorwas breaking box office records in America—they kept it on for weeks. They had never made so much money. It wasn’t shocking to the audience it was aimed at.What was your view about the whole video nasty hysteria, as someone who had been making fairly groundbreaking horror films years before without complaint?Well, the video nasties thing was all fairly random. I think they often didn’t look at the films at all. They just picked films with titles that sounded bad and tried to ban them. I rememberDriller Killer—it was alright, it was just a bit silly, really. I was quite happy some of them were banned because they were just rather silly.Nightmare in a Damaged Brainwas the main one people were upset about—it should have been banned for being a terrible film, but it is so ludicrous that I don’t think it could have affected anyone negatively.I Spit on Your Grave, however, caused uproar because of the sexual nature of it—rape is very dicey, always has been, for obvious reasons.But your films were heavily sexual. The first films you directed were sex films, weren’t they?Yes. They were softcore, if you saw them now they would seem silly. The first was calledHer Private Hell.I had been working as an editor on documentaries and commercials, and obviously I was always trying to get someone to finance a film for me to direct. I was so frustrated that I decided to make a short film. It was running at a cinema in South Kensington and a friend of the owner was a distributor who wanted to go into business making low-budget films, something a bit more commercial. They needed a director for a sex film, and they were in the cinema as my film was showing, so I got a phone call.Her Private Hellis not great. It stands up OK today. But back then the film was an amazing success. It was the first British sex film that told a story. Before that it had been people playing tennis at a nudist camp. But this was a 90-minute drama about a girl being exploited in the fashion business, along with lots of people taking their clothes off. There was one cinema where it ran for 24 months doing ten shows a day. The second sex film,Loving Feeling, was also successful, but not as much so. Other sex films were starting to compete. Still, it did fine. They asked me to do a third, but I said no. Working with naked ladies gets very boring from a director’s point of view—it’s just people taking clothes off and getting into bed.Did you ever have to hold yourself back from certain levels of violence, sex or gore?Not really. We were never doing anything we thought would offend anyone, we weren’t setting out to cause offence. Strangely enough,Terrordidn’t get many complaints. The censor had one main problem with it: there is a scene where a girl gets stabbed, ormanystabs, I should say, on a staircase. There were a couple of shots where the knife went through her feet, and they had to be cut. They didn’t mind a knife going through her body. I can only think whoever was examining at the time had a real problem with feet in general.Censor-wise, surely religion caused problems? Satan’s Slave must have been tough?Satan’s Slavedid get more cuts. It was 1975, and it was tricky. But at the time we were always making alternative cuts and scenes for other countries. There was a scene where a girl was whipped, naked, against a tree. They were not fond of that here, and in the end it was almost non-existent in the UK version of the film. Another scene that sticks in the mind was one where we had a girl lying on an altar with blood smeared on her body. That was fine, but we had to avoid getting any blood on her breasts. According to the censors, blood on the breast would make men likely to commit rape!We made one scene inSatan’s Slaveexclusively for the far east market. It was a very gratuitous bedroom scene. I was never fond of it, it wasn’t horror, it was just intimidating and nasty. The girl was tied, spread-eagled, to the bed and threatened. There was no blood, but it was very brutal. She is semi-suffocated, then her clothing is cut off with scissors before the man, played by Martin Potter, threatens to cut off her nipples. It was horrible.Was Satan’s Slave your main battle with the censors?There was a lot of fuss aboutInseminoid. In fact, it was mainly successful because lots of women’s groups tried to ban it. There was a part in the film where a woman is inseminated by an alien and gives birth to a monster, but apparently giving birth to a monster is a very common nightmare for pregnant women. We didn’t know that. They said we were exploiting women and their fears. It was great publicity.

Satan’s Slave (1976) Click to enlargeSatan’s Slave (1976)So where did it go wrong? Why did you stop making films?I did a film calledGunpowderafterInseminoid, and it was a complete disaster. A fake Bond thing, it needed helicopter chases and all that. And it was planned to shoot in the summer, so I thought it would be great fun. But it was pushed back to November and the producer wanted to film it in Macclesfield of all places. By the time we started filming, it was snowing, the whole thing was a nightmare, no props, nothing. There was one scene with an atomic submarine—we asked the producer how we were meant to shoot this and she actually suggested we use a piece of guttering with a curved end and push it through the water like a periscope.It sounds sort of amazing.It wasn’t. It was terrible, and is very hard to find today. I then got the chance to do a film calledBloody New Year. It was a good script and could have been a good horror film. But once again the producer screwed up on it and it was ruined. Following theGunpowdermess, it was too frustrating. That was what put me off films. I went back to commercials. I had a nice line doing commercials for kids’ toys at Christmas time. It was great. They paid well and were a doddle to make. I did music videos for Gary Numan, too, and actually made a documentary with him about an air show calledWarbirds. That was great fun, not that I knew anything about airplanes.The original soundtracks toPreyandTerror, composed by Ivor Slaney, have just been released for the first time by Moscovitch Music.

Satan’s Slave (1976) Click to enlargeSatan’s Slave (1976)So where did it go wrong? Why did you stop making films?I did a film calledGunpowderafterInseminoid, and it was a complete disaster. A fake Bond thing, it needed helicopter chases and all that. And it was planned to shoot in the summer, so I thought it would be great fun. But it was pushed back to November and the producer wanted to film it in Macclesfield of all places. By the time we started filming, it was snowing, the whole thing was a nightmare, no props, nothing. There was one scene with an atomic submarine—we asked the producer how we were meant to shoot this and she actually suggested we use a piece of guttering with a curved end and push it through the water like a periscope.It sounds sort of amazing.It wasn’t. It was terrible, and is very hard to find today. I then got the chance to do a film calledBloody New Year. It was a good script and could have been a good horror film. But once again the producer screwed up on it and it was ruined. Following theGunpowdermess, it was too frustrating. That was what put me off films. I went back to commercials. I had a nice line doing commercials for kids’ toys at Christmas time. It was great. They paid well and were a doddle to make. I did music videos for Gary Numan, too, and actually made a documentary with him about an air show calledWarbirds. That was great fun, not that I knew anything about airplanes.The original soundtracks toPreyandTerror, composed by Ivor Slaney, have just been released for the first time by Moscovitch Music.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement