A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Recently I was looking around at the state of modern image editors and discovered something really disappointing.

Videos by VICE

The issue? Well, even with the rise of modern Photoshop alternatives such as Affinity Photo and Pixelmator, these image editors are not designed to handle animated GIFs. Which means that, despite the fact that I’d certainly love to see what life is like outside of the world of Adobe, it looks like I’m stuck in that ecosystem for a little while longer.

Don’t get me wrong: Adobe’s software is great, if a bit expensive. But I do think that its business model highlights just how consolidated its power actually is—and it’s not talked about nearly enough in the creative space.

Let’s discuss how Adobe’s became the center of the creative ecosystem, and why that should be of concern.

Why Adobe is too powerful and needs some competition, stat

Days before I started writing this, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), who is running for president, made the case for breaking up the tech giants. She meant Google, Amazon, and Facebook in particular.

But honestly, if we’re going to be talking about tech monopolies, I wish that Adobe was on her list.

Adobe isn’t a social network, search engine, or e-commerce giant—it’s largely a provider of services to the creative field, particularly in marketing and editorial realms. And Adobe has become an important part of that ecosystem, having originated many of the best ideas for creative software over the past 35-plus years. PostScript, a fundamental programming language used in desktop publishing, is an Adobe product through and through. The PDF, an open standard spearheaded by Adobe and based on PostScript, is literally the most important file format ever created. And tools like Photoshop, Illustrator, Premiere, and InDesign are best in breed and are involved in the creation of much of our printed and digital media. They help get the world ready for its closeup.

But there’s a problem, and it’s long been lingering in the background: Adobe is too powerful and can ignore things it doesn’t want to do—whether in the form of cutting prices or ignoring usability concerns—in part because it carries itself like it’s the only game in town.

Here’s a case in point that matters a lot to me, actually: Apple has supported a native fullscreen mode in Mac OS since 10.7, better known as Lion. It’s a fundamental feature, and helps keep windows well-sorted on laptops in particular. It works pretty well in every major Mac application—except Adobe’s.

Adobe, out of interest in consistency in its own apps over the broader user experience, has largely refused to support this basic feature released way back in 2011, choosing instead to rely on a nonstandard full-screen mode that doesn’t work with Apple’s windowing system and lays itself on top of all your other apps. This makes it a pain to use on laptops in particular—a problem considering much of Apple’s user base is on a laptop.

(The only exception to this is the photo editing app Lightroom, which added support a few years ago; however, despite a lengthy thread making the case for it on its forums, the company has effectively decided to keep its own MacOS interfaces consistent with other platforms, rather than supporting Apple’s own native features. An official explanation dating to 2012 has cited weaknesses in Apple’s own fullscreen mode implementation that have long since been addressed.)

Worse, if you drag a picture from a web browser into Photoshop, the window moves and doesn’t stay in the middle of the screen, creating a constant frustration that could be remedied if, again, Adobe bothered to support the native fullscreen mode that has come in Mac OS for the past seven and a half years. I would literally chew off my own arm to get Adobe to support this feature, even though it would make it impossible for me to properly use its software in the way I’ve been accustomed.

(In its defense, the open-source Photoshop alternative GIMP doesn’t support it, either, but at least it’s talking about fixing it—and it has the excuse of being a ported-over X11 app!)

This isn’t the only example of this foot-dragging. In 2005, Apple announced it was moving to Intel processors the next year, and Adobe was quoted in a news release saying it would support the new Intel processors on MacOS. However, when the first machines came out in 2006, Adobe didn’t adjust its release schedule to add “universal binary” support to existing versions of its Creative Suite software, instead making Mac users wait almost an entire year for the most popular application suite to natively support the latest Apple hardware.

The irony was that one of its flagship applications, Adobe InDesign, eventually leapfrogged over the desktop publishing competition, the still-made page layout tool QuarkXPress, in part because it quickly released a Mac OS X version when its maker, Quark, was taking its sweet time to upgrade its software to the modern platform.

When the Intel shift happened on Mac OS, Quark learned its lesson and released an update way quicker than Adobe did—but the market inertia that allowed Adobe to get a leg up had already shifted away from Quark by this point.

Cracks in Adobe’s model have only emerged in the past few years, with tools like the UI-focused Sketch (as well as the aforementioned Affinity Photo and Pixelmator) gaining popularity. But it remains powerful because of reasons similar to Microsoft’s ownership of the office suite market. If you convince enough offices, enough schools, and enough individual users that a certain tool is the best one—and, importantly, you make it hard to stop using that tool—the maker of that tool has the ability to essentially do what it wants.

I don’t think Adobe is untouchable, but I do think that its taken advantage of its market position in a way that harms the long-term health of the creative community. It has traditionally charged hundreds of dollars for its software suites (creating a barrier for people just getting into the field and encouraging piracy of its tools), then changed to a cloud-based model that was also quite expensive, and then started raising prices.

What really worries me about Adobe is its ability to kill a tool that people like simply because it wants to. Which brings me to the story of FreeHand—an Illustrator-like vector drawing tool, popular in the early years of MacOS, whose existence proved controversial during not one, but two Adobe mergers, and helps explain how Adobe became dominant.

How FreeHand exemplifies the cutthroat nature of the desktop publishing industry

The Apple Macintosh computer was a groundbreaking tool for the publishing industry, one that lowered the barriers to entry for graphic designers and printers while raising the general quality of work. A big part of that had much to do with the quality of the software tools that came to maturity in 1980s and helped to bring the creative field to life.

Adobe was directly responsible for some of these tools—it first released the vector graphics program Illustrator, based on Adobe’s existing PostScript file format, in 1987, and bought the rights to the raster-graphics program Photoshop from brothers Thomas and John Knoll in 1988—but not all of them. There were lots of competitors in the space and it was not immediately clear which ones would win out in the long run.

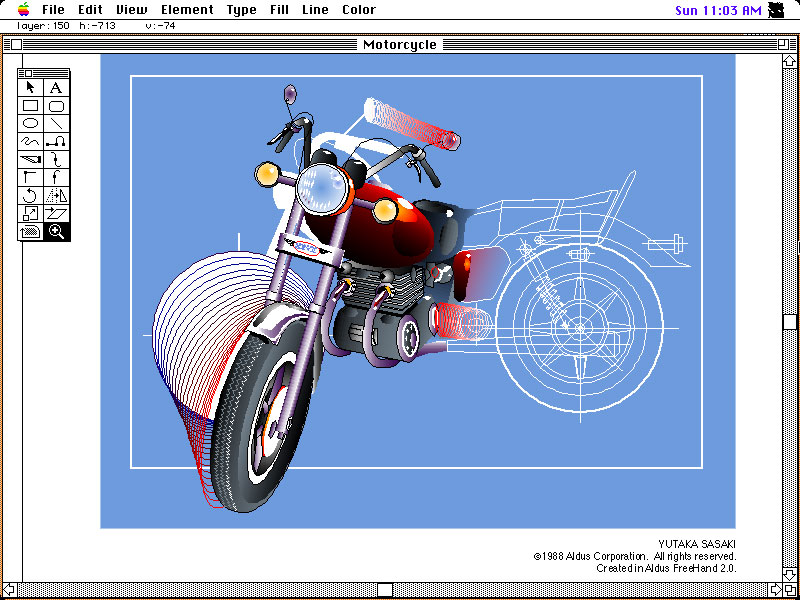

One of those competitors was FreeHand, first developed in 1988 by the company Altsys. For much of its early history, the software was marketed by the company Aldus for the Apple Macintosh market, though Altsys created a separate version for NeXT computers called Virtuoso. Beyond selling FreeHand, Aldus famously created PageMaker, a layout tool that helped to create the desktop publishing industry.

While Adobe Illustrator immediately showed itself as a formidable player on the market, it was by no means the only one. Both FreeHand and CorelDraw—the latter of which came out in 1989—kept Adobe on its toes.

A 1990 product comparison in InfoWorld highlighted how cutthroat the competition between FreeHand and Illustrator had become—the two applications received equal reviews, but FreeHand was clearly given the upper hand from a pure usability standpoint.

“Although Illustrator had a head start in the marketplace, FreeHand is making a serious run at Illustrator by offering more features and flexibility,” the magazine stated.

Both tools, of course, had their partisans who preferred one program’s take on bezier curves over the other. But with desktop publishing becoming an increasingly competitive space—QuarkXPress emerged as a strong competitor to PageMaker during the early 1990s—it was only a matter of time before things got messy.

That mess surfaced in April of 1994, when Adobe agreed to merge with Aldus in a deal initially pinned at $525 million when it was first announced, according to The Seattle Times. The Times described the merger as one that was simply the best move for both companies—one of which built most of the standards for printing documents using a computer, and the other which had developed a key piece of software that made those standards functional.

“We believe our two companies, each with a rich history of inventing different aspects of the electronic publishing revolution, are simply much stronger together—both technologically and financially—than they would be by remaining separate,” Adobe Chairman John Warnock said at the time.

There were just two problems with this situation, both of which related to FreeHand: One, Aldus didn’t develop FreeHand, so there was a whole other company to consider, and that company wasn’t happy; and two, putting FreeHand and Illustrator into the arms of the same company screamed anticompetitive behavior. That’s how the Federal Trade Commission saw it, anyway.

Altsys sued Aldus, which led the FTC to take notice of the merger and nearly ended the whole thing. Fortunately for the sake of the merger, cooler heads prevailed: Aldus agreed in a settlement to give Altsys the rights to FreeHand, which allowed the deal to go through.

Soon after, Macromedia, the firm behind Director, an interactive authoring tool then popular with CD-ROM based multimedia software, quickly snapped up Altsys and made Freehand (with a lowercase H) a key part of its software offering. It was a perfect merger of company and tool—as proven by Macromedia’s eventual creation of some of the internet’s earliest pieces of professional software, Dreamweaver and Flash.

Adobe owned the print side of things, especially after PageMaker was retired and InDesign started to eat Quark’s lunch. Macromedia was an internet-friendly force. Of course they were going to merge.

And merge they did when, in 2005, Adobe bought the company out for $3.4 billion in stock.

Which meant that FreeHand, once again, was caught in the middle of a big corporate merger with Adobe. A lot had changed in the prior decade, however: While FreeHand was still an excellent tool, vector drawing tools weren’t quite as important in the scope of the merger as the technologies that had gained momentum in the decade prior. The two most important non-HTML distribution tools on the internet at the time were Macromedia’s Flash and the Adobe-borne PDF.

The merger led to the killing off of a number of popular tools made by each company—Adobe’s GoLive, which was less prominent than Macromedia’s Dreamweaver, was shown the door; so too, was Adobe’s ImageReady, a Photoshop companion program that couldn’t compete with Macromedia’s Fireworks.

But FreeHand was different—it had a history and a fanbase that hadn’t been worn down by Creative Suite. Still though, business decisions needed to be made, and FreeHand—a program once considered so important to the industry that the FTC got involved—was voted off the island.

The fanbase, to put it lightly, was not happy. And they did something pretty brash in response.

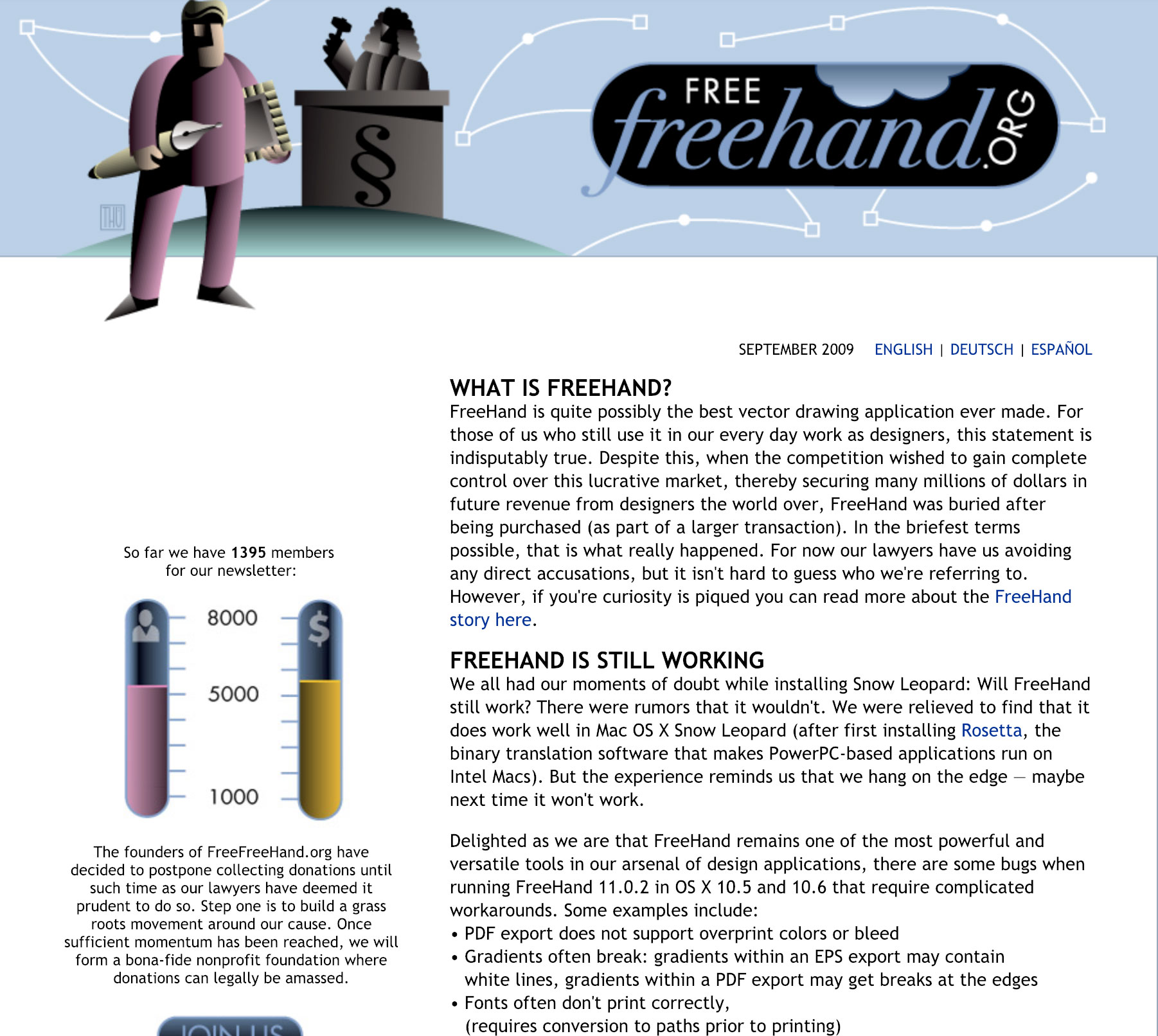

“Our wish is a simple one: For those who still use FreeHand today (and don’t want to use Illustrator, possible reasons for which are myriad) the application must be brought up to date and maintained, i.e. known bugs fixed and made to work natively on current operating systems. We don’t believe this is asking too much.”

— A press release for a group called Free FreeHand , which aimed to make the case to keep FreeHand, still a popular tool among some circles of designers, alive. The initiative was led by Thü Hürlimann, a former art director for the Swiss versions of MacWorld and ComputerWorld, as well as designer Jabez Palmer. These were two people who had been using Mac-based design tools for nearly a quarter century by the time Free FreeHand came about—and they found thousands of supporters for their cause in a short period of time. Which is something you need if you want to file a class-action lawsuit.

The FreeHand fans that literally sued Adobe for killing FreeHand … and gave Adobe a scare

In an era before Change.org became the popular way to protest, Free FreeHand stood out because of its sheer passion.

The desktop publishing industry that Adobe and Macromedia and Aldus had fostered was rising up and defending their right to use the tool they wanted. Their ask was simple: Keep FreeHand alive, and ensure it remained updated for the latest versions of Mac OS X and Windows. And if Adobe didn’t want to do it, free the code to the masses. Nothing against Illustrator, but FreeHand was their tool of choice—and they weren’t giving up without a fight.

“We want FreeHand to have a future,” the press release stated.

What’s fascinating about this effort is that, rather than simply launching an online petition as they did in 2009, the designers eventually went for legal relief, filing a class-action suit against Adobe in 2011, in response to the publisher’s move to shut down the development of FreeHand.

The FreeHand fans argued passionately that Adobe’s decision to shut down FreeHand development represented anticompetitive and monopolistic behavior under federal law, and that the merger violated a California law that prohibited such activity. It also wanted the source code to be released to the public so that FreeHand could be developed as an open-source program.

Not everyone understood exactly why FreeHand fans were willing to go to all this trouble, especially in 2011, when FreeHand had been off the market for nearly half a decade. (“For the life of me, I don’t understand why folks love FreeHand so much,” my friend Charles Apple, a design consultant in the newspaper industry and an Illustrator fan, wrote of the lawsuit in 2011.) But to their credit, their case got a lot further than one might have assumed.

The suit didn’t entirely go the plaintiffs’ way, admittedly—the California law violation was thrown out, and the pitch to open-source the code was cast aside. Nonetheless, US District Judge Lucy Koh genuinely did raise the specter of Adobe breaking federal antitrust law with the Macromedia merger—as Koh did initially find that there appeared to be evidence that Adobe had violated Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which makes it a felony to conspire to monopolize a market. From a 2012 decision in Free FreeHand Corp. v. Adobe Sys. Inc.:

In summary, Plaintiffs have plausibly alleged that Adobe willfully acquired monopoly power and maintained that power through anticompetitive conduct. If, as alleged, Adobe ceased the development of FreeHand while steering existing FreeHand users to a bundled product, thereby further raising already high barriers to entry, it is plausible to infer that this conduct tended “to impair the opportunities of rivals” and “did not further competition on the merits.”

This, wrote Koh, gave the plaintiffs enough to go on to continue discovery.

“Reading the alleged facts in the light most favorable to Plaintiffs, it is reasonable to infer that Adobe’s discontinuation of FreeHand, in aggregate with Adobe’s other conduct, reduced competition,” Koh stated in the decision. “Accordingly, Plaintiffs can attempt to adduce evidence in discovery to support this allegation.”

Koh, it should be noted, tends to get a lot of tech-related cases, due to her position as a federal judge in Northern California—among the cases she heard around this time involved Apple’s suit against Samsung.

This ruling clearly got in a few tidy cuts against a sitting giant in a decision made by a judge who knows Silicon Valley like the back of her hand. So where did the case go after that? Simply put, Adobe cut a deal with Free FreeHand in 2012, reportedly in the form of discounts for Adobe products and a promise by Adobe to consider adding FreeHand-y features to Illustrator, and the legal effort turned into a forum.

“While no stone was left unturned in the effort to bring FreeHand back into development and return it to market viability, in the end this proved to be an impossible goal,” the current site, FreeHand Forum, states.

FreeHand diehards are still out there. Some of that passion has led to the creation of alternate tools, such as Gravit Designer, which was later acquired by Corel. The users created a specific file loader for the virtualization software Parallels that allows FreeHand fans to have a copy of this program on their modern machine. And Thü Hürlimann even went to the trouble of building a Hackintosh that runs the 12-year-old Mac OS X variant Snow Leopard, just so he could always run the last version of FreeHand on modern hardware.

In the end, though, Free FreeHand’s efforts weren’t successful. But one has to wonder what might have happened if it was. Would Adobe have changed its tune or faced more regulatory scrutiny?

Would we even have the expensive ball of yarn that is Creative Cloud?

I like Adobe and most of its products. I use many of them daily, and love using them, often together. (I admit I’m more an Illustrator guy, though my favorite Adobe tool to this day is InDesign.)

But I also realize that Adobe has power thanks to its consolidation of tools that makes it problematic for the future of creative design. The suite gives it all of its power—and that power gives it too much influence over how we work.

Last year, the creative giant bought two fairly large firms. First, it spent $1.68 billion on Magento, a firm that sells e-commerce software, and then, last fall, it bought Marketo, a firm that sells marketing software, for $4.75 billion. These tools, together, represent two of the four largest acquisitions in Adobe’s history, with Marketo actually worth more than Macromedia, a buyout that fundamentally changed the company.

Adobe is increasingly not only trying to run the software that can create your flyer or logo or commercial, but it’s trying to own the whole marketing process, too, soup to nuts. Some companies might love that sort of integration, and it’s a big reason why Adobe is making all these aggressive acquisitions. But a single company with that much power over a single field is worrying.

I really like Adobe as a company, but I think its suite has become so costly and unavoidable for the average creative consumer that it needs to be a little bit smaller, so as to allow smaller players to compete without feeling like they have to go up against an impossible behemoth to even make a dent. Maybe Adobe fans won’t like to hear this, but I swear my case here is for the creative community’s best interests.

Make Adobe smaller. Make it possible to live without it as a creative. Make it small enough that it can’t crush an app like FreeHand ever again.

And make it small enough so that when users repeatedly ask it to support the native fullscreen feature in Mac OS, it actually listens, because it’s driving me goddamn crazy that it hasn’t added it yet after almost eight years.