A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

In some ways, social media started with a bet by a bunch of startups that, if presented the right way, regular people would share whatever they wanted to on their platforms without expecting any sort of compensation.

Videos by VICE

Give them a place to list their profiles or share their thoughts, get a little ego stroke, and they’ll be totally fine with sticking around for free. Sure, you actually go to Twitter because of the people, but the people who run the network get all the money even if you generate a significant amount of their traffic. (It makes you wonder if a certain former president will send an invoice.)

This is a weird line of thinking, I know, but given the recent news involving Tumblr, I kind of got curious about whether there was a situation where this equation flipped—where people were using a platform for free and suddenly expected to get paid for it. And it turns out, there was.

And it was a biggie: The version of AOL that entered millions of homes via dial-up lines in the late 90s, thanks to an army of volunteers that carried the network’s weight on their unpaid shoulders.

14k

The number of volunteer moderators that America Online had at the turn of the 21st century, according to a 2000 assessment by The Washington Post, which described these volunteers as “the police, tour guides and construction workers in AOL’s virtual world.” This relationship became strained when some of these volunteers put two and two together and realized, hey, we’re making billions of dollars for AOL.

When we paid for online access by the minute, people volunteered to manage networks to stay online longer

You’ve most assuredly, over the years, seen one of the many stories written about Facebook’s treatment of staff members and contractors who work to moderate the massive site—as low-paid contractors working what must be one of the hardest white-collar roles imaginable.

Perhaps you couldn’t understand why content moderation was at the bottom of the food chain for social media platforms, despite the fact that it’s such a front-facing interaction.

But the truth is, decades before Facebook found itself heavily criticized for its poor moderation, its predecessors weren’t even paying the moderators at all. Not even on a freelance basis. If they were lucky, they might get a discount on access—a good deal back then, given that people paid for online access by the hour in those days.

Still though, we were leaning pretty hard on unpaid moderators to provide basic functionality on our early online networks.

Now, to be clear, there is a degree of modern context being applied to a vintage activity here. We didn’t have terms like “gig economy” in 1991. And on top of all that, commercial online services were limited in the early days of online culture. There was an expectation that things were just built and used on a volunteer basis, perhaps an extension of the formative bulletin board systems.

As researcher Hector Postigo wrote in a 2003 analysis of AOL’s relationship with its volunteers:

The relationship between AOL and its volunteers in the early 1990s had been established under the influence of the early Internet community spirit present in other Internet communities, such as Howard Rheingold’s Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link (WELL) and the various Usenet groups of hobbyists and information enthusiasts engaging in what has been described by some observers as a gift economy of information exchange.

Whatever the case, during the 1980s and 1990s, it was very common for many online networks to rely on the unpaid services of their users to help onboard or support others within their communities, a role that would later be taken on instead by paid individuals.

In many ways, these users were online networks’ front line to customer support, and often received only modest compensation in return. In a 1996 article for Online Access, one user’s unpaid role is validated as such:

Why do users volunteer to help? Some do it as a way to socialize (though the online services try to make sure that the messages for the most part stay on topic). Some want to give back to the services they care about. Gail Kruggel, a volunteer sysop in Compuserve’s help forums, spends several hours a day helping members on Compuserve. She does get a free account out of the deal.

“But I also get a large measure of satisfaction from being able to help new members,” she says. “I remember what it was like to be new online, and it can be very scary.”

And as new networks emerged, the networks saw it as a way to bolster technical support. When MSN launched in 1995, the company put significant resources into bolstering the design of its forum moderation capabilities, which were seen as a way to get developers interested in using the service to offer technical support, the kinds of roles that were at the time given to volunteers.

In her 2001 book From Anarchy to Power: The Net Comes of Age, author Wendy Grossman explained that early online networks like AOL (originally Quantum Link) and Compuserve were built off the backs of volunteers like these, with a big reason why such networks could get away with it being the fact that the high costs of the network made it the best choice for the Extremely Online.

“In the early days of these services, when users were charged for every minute they stayed connected, some of the more successful contract owners made a very good living from their royalties, and free accounts might save volunteers hundreds of dollars a month in online charges,” she wrote. “The more generous ones passed some of their revenue stream on to the volunteers; certainly some paid for training and other benefits.”

She added that this work was extremely difficult despite its generally unpaid nature. “You work with all eyes on you and everyone ready to accuse you of censorship, the online equivalent of throwing someone in jail without trial,” she added.

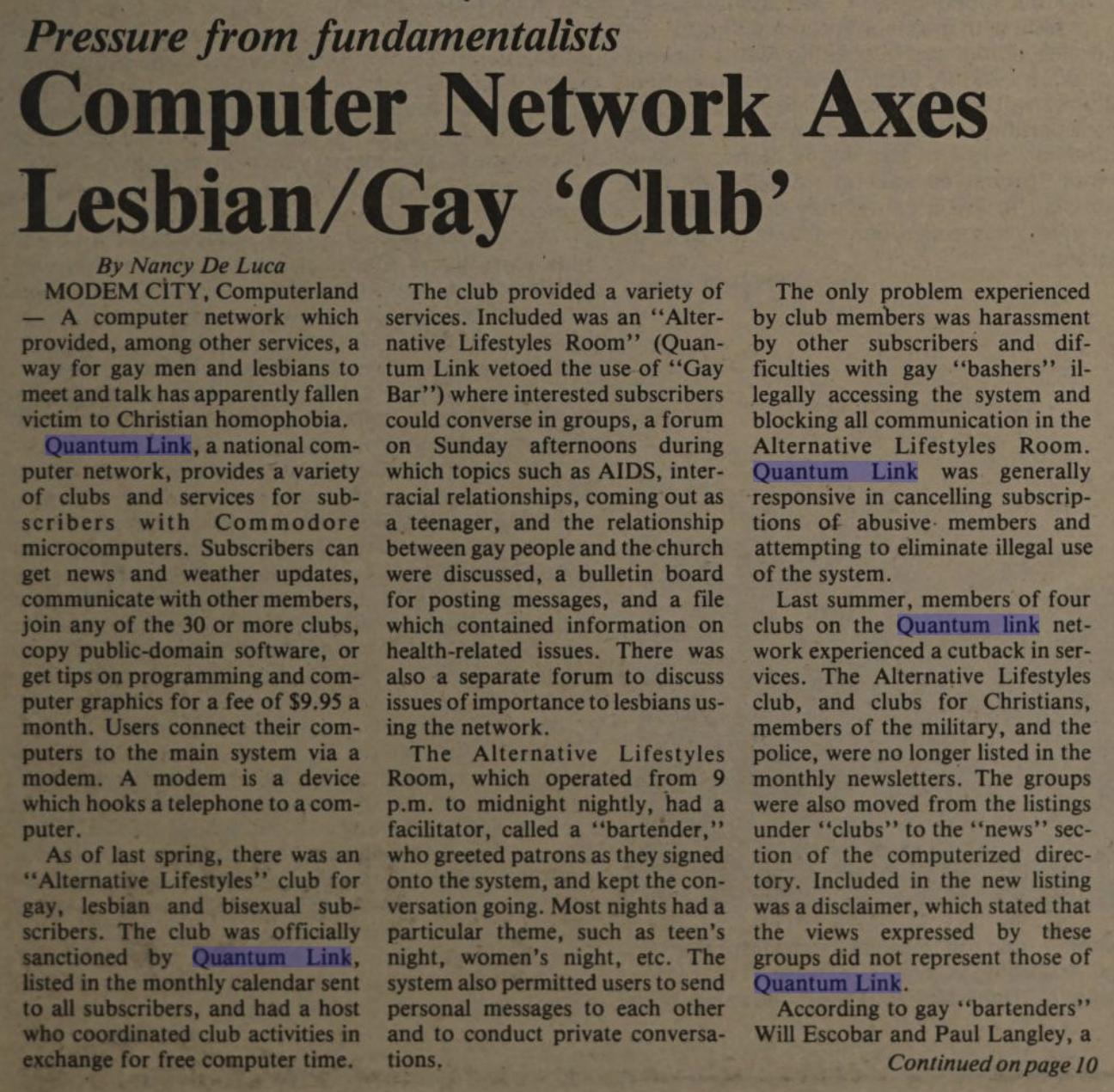

And at times, the decision-making could be transparently arbitrary and damaging to both communities and moderators. In one example I found in a late-80s LGBTQ publication that would be considered scandalous by today’s standards, Quantum Link was accused of shutting down its “Alternative Lifestyles” group at the behest of Commodore, which felt pressure from one of its distributors that had been built on fundamentalist Christian principles, a mail-order seller named Protecto, that had a large financial stake in Commodore at the time and which had paid off some of the computer-maker’s debts. Quantum Link’s marketing team had reportedly pressured the company to minimize the group’s presence.

Further, the moderators of the group, who called themselves “bartenders” as the group utilized a gay bar metaphor, accused Quantum Link’s then-vice president, later AOL CEO Steve Case, of limiting the group’s reach because the company did not want to get involved in political issues.

Combined with the fact that these volunteers generally weren’t getting paid, one gets the impression that the operators of these online services held all the power. In her book, Grossman underlines this point by noting that niche communities greatly suffered when they were no longer as financially viable, in part because the incentives changed:

But as competition increased, services dropped their prices, cutting the contract holders’ revenue. When the services went flat-rate to compete with ISPs, the economics changed entirely. Where under the royalty system a niche area could do reasonably well with a small but loyal band of devoted users, under flat-rate both the service itself and the content provider had to come up with new sources of revenue, such as selling related merchandise, or advertising. Either required a large audience, with the upshot that both services rapidly began shutting down the quirky niche areas and focusing on the mass market.

Of course, AOL grew greatly off the back of the mass market, and under the weight of AOL’s growth was a large network of volunteers that helped keep the community running. Eventually, the volunteers put two and two together.

“AOL requires potential community leaders to attend online meetings, during which they’re given an overview of the training program and encouraged to ask questions. Some drop out voluntarily once they realize the time, dedication, and scrupulousness that’s required of an AOL community leader. Other applicants are dismissed by the trainer for demonstrating a lack of maturity or inability to follow the rules. In either case, these sessions help filter out applicants who are obviously not suited to being an AOL Community Leader.”

— A passage from the 2006 book Community Building on the Web, discussing the stringent requirements for community leaders on the AOL service. It’s not quite enough to be a full-time job, but it’s more than a volunteer position usually requires. And, oh yeah, it’s at the behest of a company that at its peak had a market capitalization of $200 billion.

Why AOL eventually faced lawsuits over its volunteer program

In 2010, at a time when AOL’s dial-up service had largely become a closed chapter in the history of digital technology, the company found itself having to pay $15 million dollars to former members of its AOL Community Leader Program, an initiative that dated to the early 90s, at a point when few people had ever even used a web browser.

It was an extremely long, drawn-out legal battle. And AOL had done everything in its power to avoid the inevitable result. But in the end, AOL was on the hook for paying something to all of those volunteers.

Initially called guides, the program started with noble goals, as all things do. With AOL being a small online network, people who joined the service might need the occasional helping hand, or they might need someone to knock them back into line if they do something wrong. After all, for most people, AOL was their first foray into the digital world, and how were they supposed to know how big this whole thing was going to get?

And to some degree, volunteer work seemed like a good idea. It probably looked great on a resumé, it let people be online for longer when it was still a novel concept, and it probably was a lot cheaper than paying full price by the hour. And early volunteers noted that things seemed welcoming at first. One first-person account on the defunct website Observers.net claimed they were convinced to volunteer by Steve Case himself:

I think he used the name SteveC or SteveCase at the time. And he seemed to genuinely care. I thought it was great that he actually wanted input from me. Here I am, this confused and frightened newbie, and this guy is asking me what he can do to make the service better. I told him that I thought it was great that someone had this service, and it was great that he wanted to know how to make it better. I told him that I liked what I had seen, but that there needed to be more than just chat. I wanted to be able to find my news and maybe learn a thing or two.

But as AOL grew, the AOL Community Leader Program didn’t shrink. In fact, it grew more bureaucratic over time, requiring more and more of its helpers. Joining the program eventually involved a three-month training process as well as shifts and scheduling. With a requirement that volunteers work four hours a week, it wasn’t going to compete with a full-time job, but it definitely chewed up more of your time than the occasional volunteer gig.

Of course, AOL’s dominant position in late-90s society meant that others outside of the AOL bubble noticed the program, too—and that the volunteers were eventually realizing that they weren’t volunteering; they were working for what would eventually become a Fortune 500 company, with compensation that was significantly less than minimum wage.

And as chatter about AOL going unlimited became more common, chattering began to emerge among community leaders about going on strike against AOL for this thing they were doing on a volunteer basis, in part because of the additional work that was expected as the network went unlimited. On top of this, AOL was concerned about tax liability around the special accounts they gave these volunteers free access to the site, and changed the model to instead require these volunteers to use standard for-pay accounts, with credits for usage. It led to an infamous incident called the “Row 800 Incident,” in which numerous guides expressed an interest in going on strike. It was a mess that led to a whole bunch of volunteers getting booted.

Around the same time, volunteer Errol Trobee actually sued the company for back wages (he wouldn’t be the last), leading to a collective freakout internally as the organization realized it had created an untenable situation with thousands of vaguely trained volunteers who weren’t getting anywhere near a realistic compensation for the work they were doing.

“There was no consistency to it,” onetime AOL employee Ann Reed told Forbes in 2001. “A lot of people were working a lot of hours, and AOL realized they were not paying them anywhere near minimum wage.”

Over time, the program gained increasing negative attention, culminating in a 1999 Wired article that called the program a “cyber-sweatshop,” as well as a Department of Labor investigation, and the beginnings of the class-action lawsuit that took more than a decade to resolve.

As a result of all this drama, AOL began to rein in the volunteer program, first cutting off a teen-targeted element in 1999, limiting public-facing volunteer access to internal tools, and shutting the program down entirely by 2005.

In some ways, the problem might have been that the volunteering program was too successful, which made AOL significantly more reliant on it for its growth.

There’s this concept in the nonprofit space called “microvolunteering,” in which people are asked to pitch in with the occasional small task to help keep things moving. The small task might be a reply to a forum thread or taking someone’s question. But the AOL program was decidedly not that.

“Their hours? Flexible: Some work as few as four per week, others put in as many as 60,” Wired writer Lisa Magonelli explained. “Their pay? A $21.95-per-month AOL account “empowered” with some special CL-only enhancements. Their job satisfaction? High. Until now.”

If you’re volunteering 60 hours a week for a large company, you’re not volunteering anymore. You’re working for free.

“These may just be a few voices of indignation among the many thousands of bloggers, most of whom are happy to write for free because of the readers and cachet it brings them. But the grumblings of dissent can grow, as they did in a similar situation in the early days of the Web.”

— Lauren Kirchner, a writer for the Columbia Journalism Review, pointing out the parallels between AOL’s Community Leader Program and the Huffington Post’s unpaid contributor program, which AOL was purchasing at the time Kirchner wrote this in 2011. (Yes, it’s ironic that AOL bought this, given the stuff I just wrote in the prior section.) The company eventually dropped the contributor program entirely as social networks effectively replaced its value proposition, though HuffPost’s recent acquirer, BuzzFeed, still heavily relies on unpaid contributors to the cost of its paid employees. (More on that point in a second.)

In some ways, one wonders if the true innovation of modern social media was not its way of connecting people, at least not on its own. But rather, it was seen as a way to convince people to do things for free that in a prior generation, or with a slightly different framing, they would have expected to be paid or in some way compensated for.

The truth is, running a Facebook group, for example, is not all that dissimilar to being a community leader on AOL in the 90s. The difference is, I made the decision to run the Facebook group, but Facebook just facilitated its existence. Facebook benefits in that I’ve created a new area for them that they will be able to advertise against.

But a side effect of this is that the social network feels less of an economic incentive to moderate. Sure, Section 230 exists (and is intended to allow for content moderation, not the other way around, no matter what some misleading politicians and cultural commentators might suggest), but because the community is kept at arm’s length, the incentive turns into letting the community get away with whatever it wants to.

The Substack model, like or dislike it, is a useful innovation in this conversation because it really enables the average user to build their own community, monetize it, and manage it, with occasional support from the network. It’s more sustainable for the network, which gets compensated as successful creators scale; and more valuable for the user, who sees something for their work. It certainly beats being a digital janitor for AOL in exchange for free hours.

There are going to be questions about whether things are taken too far with these networks at times—and those questions should be asked. It’s simply their nature.

But on the other hand, given that the alternative is a potentially scandalous situation where the online service tries hiding a marginalized group’s existence because a powerful vendor complained, it may be the better of the two choices in the grand scheme.

(But for the love of God, do something; Tumblr is a great example of what happens when nothing happens.)

But I think it’s worth keeping in mind that the discussions about content moderation and the questionable ways in which large, powerful companies manage them have always been there in the digital era. And as the saga of AOL and its volunteer army shows, there is room to force these large, powerful companies to change.

If we don’t like what those powerful companies do, we should keep pushing.