Homecoming is a new series in which Chris Bethell accompanies writers to their hometowns and learns about what they used to do, where they used to hang out and who they used to know, to see what it reveals about how the UK is changing. First off, Joel Golby goes back to Chesterfield.

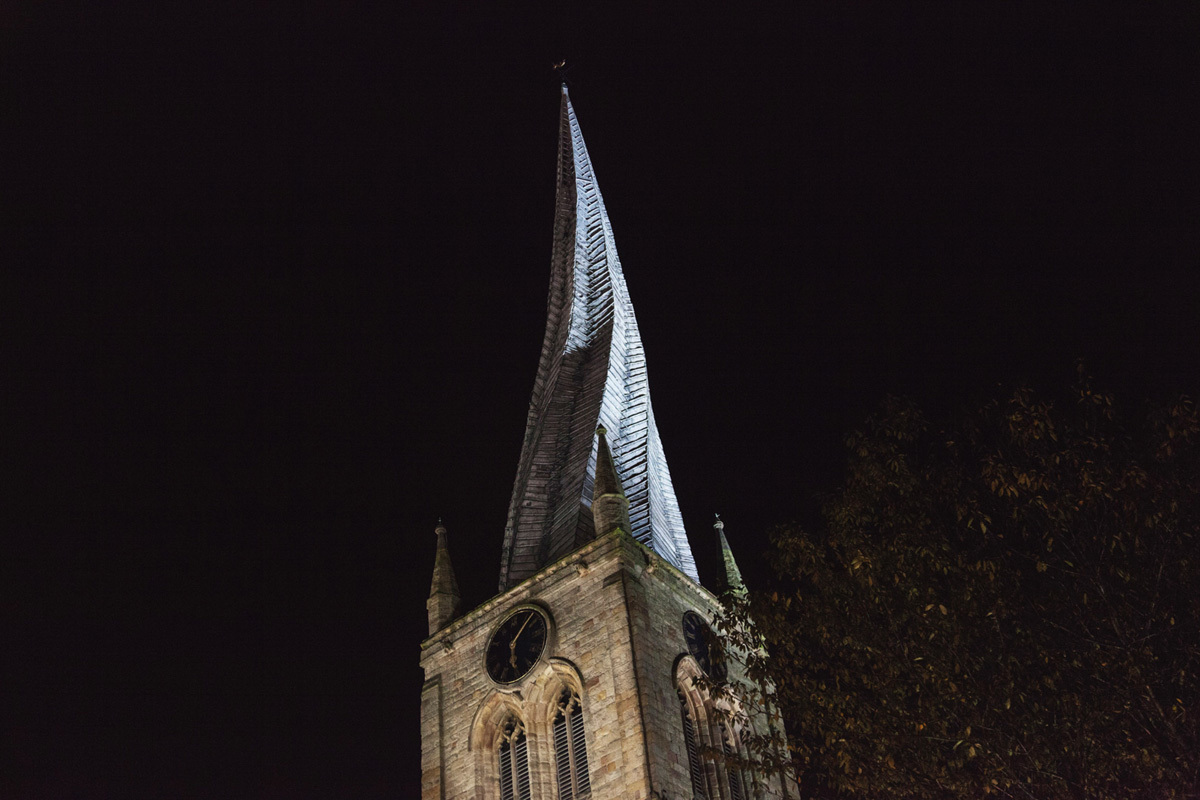

Chesterfield is a small-to-medium sized town in Derbyshire, population circa 100,000, a fine balance between ancient market town and grey unimaginative concrete, a town centre that quickly cedes to residential streets and green spaces, the perfect blend of leaf and brick. It is famous for having the most fucked up church spire in the entire actual world, for briefly having the second biggest Tesco in Britain, and for having George Stephenson die there. It is also – and this is not mentioned on its Wikipedia page, for some reason??? – where I grew up.

Videos by VICE

Chesterfields’s fucked up church spire. All photos Chris Bethell.

I say “grew up” deliberately, rather than “Chesterfield is where I am from”, because I always felt a weird disconnect with the town proper. I wasn’t born there – I moved there when I was two, from London, where my parents met and had me. Growing up I was constantly aware that there was a world outside of Chesterfield, and that world wasn’t so focussed on gossiping neighbours and long rambling letters to the Derbyshire Times about on-street parking, and bread rolls were not called “cobs”. My vowel sounds are Chesterfield vowel sounds – the u in “mug” dips like a biscuit into tea; I have not successfully enunciated a t since the start of the millennium. The accent here is proto-northern, aspirational Yorkshire – and yet sometimes I will still say “station please, mate” and the cabby will turn around in his seat and go, “where are you from, then?” and I will be reminded all over again that I don’t have a place where I truly belong.

Chesterfield is a place where the inverse of weather extremes happens. Drizzle sits in the air, here; the sun doesn’t blister; rain, when it moves in, doesn’t pelt. The town sits on the cusp of the Peak District, near the border of south Yorkshire, a 15-minute train to Sheffield, and that – being so close to significance, without ever erring into it – dominates the entire mood of the town. People in Chesterfield are cheerfully fed up. They are at once chatty and begrudging. There is a lot of sighing into pork pies. They call people “duck”. Everyone in Chesterfield was born in the exact same hospital. The town votes, traditionally, somewhere between Labour and Lib Dem, but opted to leave the EU. There’s a political discrepancy there, but one you can perhaps expect from a town that had the industry sucked out of it 20 years ago (the destruction of the Dema Glass chimneys was a public spectacle, and there’s something dark in the fact that the town was invited to cheer as its last drops of industry were exploded in front of it), replaced Royal Mail buildings instead. Chesterfield is very white (94.9 percent by the last census) with small Italian and Polish communities in between, but for some reason there is always, always, a town-wide rumour about plans to build a mosque. Have you heard about the mosque? I have heard about the mosque. What do you think about the mosque? Well. Remember the shellshocked look of the woman down the road the day an Indian family moved in next to her? That gives you a weathervane on how they feel about mosques.

My dad and I used to take a lot of walks when I was a kid. Dad used to march, rather than stroll, hands wedged in an old blue body warmer: we used to take this meandering route down, away from my house, crossing a bridge over an A road – bridges always freaked me out, the height and the roar beneath them – then down towards a canal path, where we would pass patches of stinging nettles and dock leaves, and wild garlic and discarded tires, and climb up through a gap in an old wire fence and cross a weird pavement-less road to get to another bridge, which I remember as a five-year-old being the tallest thing on the entire planet. Walked up it again recently. It’s well small. Kids are idiots.

Dad was a landscape photographer, so supposedly these walks were for him to go and find inspiration, to take beautiful vista-like shots of rolling green hills and lush grass, but honestly it was also because the path backed on to the golf course and he could trawl through the bush with a pitching wedge for lost balls. We were a pretty poor family, and dad used to undulate in and out of work – mainly out – and he would spend long, stretching days unemployed in the field behind our house, patiently pitching golf balls he’d found on our walks up high into the pale blue sky, down into a bucket. The field was the same one that, littered with dog shit and old cider bottles, our primary school would have occasional sports days, and I always remember kids stood behind me, watching from a distant as my dad smoked a roll up and played golf, whispering, “who is that man?”

At the end of our walks we would find our way back to dad’s car, a 20-year old maroon Volvo called Ruby, parked at the top of Tapton House, and I would challenge him to a race: him and Ruby, a car, vs. me, a tiny child. I would run until I panted and turned pink, always winning, somehow, gloating at the bottom of the hill after another pelting win. (It only struck me when I was about 16 that, obviously, he was easing off the gas and that I, a child, could not outrun a car).

Every Friday at about 6.30PM, I would phone an order up the road to Torino’s for a half tuna-sweetcorn, half mortadella pizza, then go and collect it – sat nervously on shiny vinyl seats inside while already-drunk people from the pub across the road would come and loudly order chips to sop up the WKDs – then slink home to eat the entire thing on my own, cross legged in front of Robot Wars. It was my routine, my ceremony.

I went to a secondary school called Brookfield, which apart from a logo change and a few more fences, hasn’t fucking changed one bit. Everyone thinks their secondary school is the best, and mine was no different: our direct rivals were Newbold, across town, who scored slightly lower than us in test results. In the middle of town, by the football ground, was St. Mary’s, which tested higher. Also there was Parkside, who are scum. There was once a plan to merge Brookfield and Parkside, diluting our perfect Brookfield minds with unruly Parkside scum. The parents were outraged. The teachers were outraged. The playground was alight with the buzz of conceptual gossip. That was a big winter of letters to the Derbyshire Times.

In sixth form we were allowed to leave the school at lunch time and on breaks, so we would flock en masse to Henstock’s, where they did chip cobs for £1 and sausage cobs for £1.20 (you could not get a sausage and chip cob). It was a fun place to go because the people working there – a woman in a tabard and a man who looked like an Elvis impersonator who occasionally stomped from a backroom with a big scoop of chips and gloweringly put it in a heater on the side then fucked right off again – quite openly hated all the school kids in their bakery. But I never saw anyone else apart from school kids in there, ever. So it was a fine-edged balance: they needed us – we kept the lights on, we paid their rent – but they hated us too.

A few years ago they put a statue of George Stephenson outside the station and even though he is blatantly holding a tiny steam-chimney locomotive it really, really looks like he’s flipping off the entire town instead. I don’t know why they decided to do this.

A guy I used to know used to only go to this fish and chip shop and this fish and chip shop alone because, he alleged, you could go in there and ask for ‘n— and chips’ and they would smirk and then make you a portion of vinegar and chips, geddit, which you would then have to salt yourself, and I don’t know at all if this is true but i. Chesterfield is the exact sort of town where a racist fish and chip shop might dwell offering entirely migrant-unthreatened white people a space in which to say n— and ii. if you were going to open a racist fish and chip shop, you would definitely call it ‘Union Jack’. I went there once and the chips were exactly adequate.

Just behind the main centre of town is Queen’s Park, a community centre with halls and a gym and the pool everyone learned to swim in. Behind there is the park proper, which has the kind of pagodas teens with multi-coloured fringes learn to smoke in, and a pond with ducks and goslings, and a miniature train that loops the park all summer. One year my mate got a job driving that train and it turned him into this weird local hero – he had this harem of giggling teenage girls who used to congregate near his train shed to get a look of him on his breaks – because that’s what it takes to make you notable in Chesterfield. A 30-minute tutorial on how to drive a mini-train and a basic CRB check and you too can be a rockstar.

This Greggs is open until 3am on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights, and I think that is brilliant.

This is the market, which was formed in 1204. The market has three moods: during the day, when it is a sort of humming hubbub, where you can buy fresh fruit and veg and weird damp curtain fabrics and sweets and rugs and bric-a-brac and always, for some reason, one of those stalls that sells gnarly-looking multi-blade tools in thick plastic packaging. Then, after it packs up, it lies spidery and empty for a few hours, flickering under electric light. And then at night it becomes this sort of sanctuary for people who are five pints in and need somewhere to sit in silence and eat a Big Mac, which they do, sat hoiked up on the abandoned stalls with their legs circling lightly in the air above the floor, like large drunk children.

Once we were walking through the market at night – like, 4am, some dumb goth-kids-up-too-late-over-summer time – and I told my mates this thing I learned at school, which was: this fountain, in the centre of the market, has deep grooves on it from where butchers used to sharpen their blades there back in the day. My friend Lain had a penknife on him on the time (because goths) and dragged the blade down it a few times, more to pay homage to the long-dead market butchers than to sharpen his blade (I am actually quite sure he extremely fucked up his blade, doing this), then we wandered off. Only: about three minutes later, the sun smudging over the horizon, some dude in his 40s half-jogged up to us and started yelling. He was like, “you shouldn’t have that knife, you shouldn’t have that knife. That’s illegal.” And we kind of tried to ignore him and walk off but he was insistent that he was going to confiscate this penknife. And there was a moment, there, where Lain nearly handed him his knife – there’s an age between childhood and adulthood where you still automatically cede authority to grown ups – and we realised: hold on, maybe we shouldn’t hand a fucking knife to a mad fucker who is up at 4am and alone in an abandoned market. And then we ran away until our legs were knackered.

Living in a small town with nothing much to do sends you to weird places, to do weird things. It did not help that I had weird friends. We used to take long walks at night, in those summers where the sun rises early and fades away late and none of you have jobs yet but you have this restless burning energy to stay up late and shiftless, talking shit and drinking supermarket own-brand Irn Bru, and growing your hair long and rank and greasy, and sincerely thinking Eighties Matchbox B-Line Disaster were an important band. Those were the nights we used to walk to the 24-hour Tesco on the edge of town and buy Frijj milkshakes and Dairylea Dunkers and packets of those bakery biscuits – you know the ones, the good ones, the big chewy ones, the ones with Smarties in them, or Rolos sometimes – and congregate in the underpass nearby, doing stupid shit, the kind of stupid shit you can only do when you’re 17, when girls hate you slightly more than you hate yourself. We would play end-to-end football with a miniature ball. We got up on the bridge once and dropped a rock onto a pile of crackers. We, for reasons I still do not fully understand, played Fire Tennis, a game where you set fire to a tennis ball – soak it in paraffin – then ping it delicately to each other until it goes out. Hit the ball right and a perfect trail of alight paraffin sets the night ablaze. Hit the ball wrong and you accidentally set fire to some on-offer malt loaf you’d been tasked with picking up for your mum. Do not play Fire Tennis.

Another time we bought a load of end-of-the-day discounted bread and made a man out of it, a bread man. Big sourdough head. Baguette limbs with cob hands and kneecaps. We linked it together with old coat hanger wire, carried it gingerly to a main road and left it propped up on a bench. When we went to look at it the next day it was a pile of bread, pecked to shreds by passing birds and, weirdly, someone had taken all the wire out of it. In dark quiet moments of the night I still think of that:What did they do with the wire?

There was a summer, later, where we all got Really Into Pitch And Putt Golf. Sometimes you have a summer like this. It was in that summer when we all had months off from uni, or some of us had jobs but not really, but we all sort of just about had the money to do things, but not the inclination. So we got Really Into Pitch And Putt Golf. This, like the bakery outside school, went hard against the ideas and morals of the old guy operating the club shop: he was almost visibly against the idea of selling us – a gaggle of waifs and strays in unironed trousers and without a single polo shirt or lone white glove between us – each a £3 game of pitch ‘n’ putt every day of the summer. So fuck this guy, we thought. Fuck this dickhead. And we— look, there’s no cool way of saying this. We bought a million-candle torch, charged it for 16 hours, then broke onto the golf course at night to play a game of pitch ‘n’ putt gratis. Fuck the system.

This is where, in the dark blurry night, I played the best golf of my life. We were playing teams of drunk vs. stoned – this was the summer we discovered supermarket vodka and extremely rancid little joints of marijuana – and I somehow hit par or, in one case, under par. The million-candle torch started to falter by around the third hole, so we flicked the switch and started to trudge back. And then we noticed, in the blue light of a golf course at 2AM, some other man there. Just walking, in a shooting jacket, alone. And he looked at us and we looked at him. Beat. And then someone went, “fucking RUN” and we all sprinted pissed and stoned through dinks and sand traps until we emerged, panting, carrying golf clubs, into the stark glow of the nearest street light.

I think wherever you go in the UK there is always just a dude, milling about on his own at 2AM. Never is that truer here in Chesterfield.

This is my favourite urinal in the world. I shouldn’t have to elaborate on that, but I will: once my mate Party got floppy drunk and we had to help him upstairs to wee, but mid-flow we loosened our grips beneath his armpits and he fell like he had no bones until – clunk – he split his head on this urinal and fell, pissing and bleeding, bleeding and pissing, softly to the floor. Some images you can never erase from your head. I will see Party, prone and pink and pissing, until my dying day.

This is my old road, with my old school at the top of it, and everything has changed but also nothing has really changed at all. I suppose that was the weirdest part of going back: I didn’t realise I’d miss Chesterfield until I was there. It’s hard not to miss a place that has so many corners, with so many traces of yourself in them.

I don’t go back, much – I haven’t got anywhere to stay now, and it’s not like I felt any special affinity with the town anyway, so when I go home I only do so to hang out and do dumb shit with my friends, in the last few years before kids and jobs and mortgages stop us from dropping bricks from a height onto crackers. When I went to my old house, which I haven’t seen for three years or so: there was steam rising out of the flue and new curtains in the windows, a wilting Hallowe’en pumpkin on the doorstep, reminders that another family lives there now, the space is no longer my own. The primary school I went to has bricked up the entrance: the draughty old Victorian windows have been replaced with double-glazing, so it can turn so inevitably into flats. I marvelled at weird changes nobody notices day-to-day: when did the big B&Q turn into a Matalan? When did that pub nail wood to the windows and declare foreclosure? When did these odd, delicately decorated backstreet tea rooms come from? When you leave a town, it pulsates with life and death: places open, places close, memories get concreted over and bedded in with grass. Chesterfield isn’t my town anymore – it never was, really – but there are still shadows of myself lurking there, still people and places I love, and still a statistically incredible number of places to buy chips. Long may it carry on without me.

More

From VICE

-

Photo: Photo Italia LLC / Getty Images -

Photo: wildpixel / Getty Images -

Photo: Igor Ustynskyy / Getty Images -

Photo: stellalevi / Getty Images